26 Aging Populations

Emma Rutkowski and Kimberly Bomar and Ferris State University Department of Social Work

Emma Rutkowski originally started at Ferris State University as a Pre-Nursing Student.I found my way to the Social Work program and graduated with my BSW in 2018 and then completed the one year advanced standing MSW program in 2019. My passion is hospice care and I am hoping to continue as a hospice care social worker. I plan to continue my love of rugby wherever my journey takes me. I would not be where I am today without the love and support of my family, boyfriend, amazing classmates, and professors. Thank you for everything; peace, love, and happiness to all that enter this field of social work and everyone you will meet. You will do amazing things!

Kimberly Bomar graduated from Ferris State University with a BSW in 1992. I then went on to work as parole officer for the State of Michigan for 15 years and at the same time obtained my MS in Criminal Justice Administration in 2000. Some years later I moved to California where I worked for the Masonic Senior Outreach program as a care manager for senior members before returning to Michigan in 2016. This lead to my role at Catholic Charities as a Sex Offender Therapist. I then returned back to Ferris State University as a student in the advance standing program and earned my MSW degree. My heart belongs to the many seniors I’ve helped. The rewards they offer by just a smile or holding their hand, and the gratitude they show is more than words can say. I hope those who enter this field resonate with the passion both Emma and I have felt in our work within this population. They are amazing, loving people who believe we are providing a service to them, while in fact, they are fulfilling our lifelong campaign for devotion. My contribution to this chapter as co-editor is dedicated to my mother who is my amazing rock, my daughter, who I strive to emulate, and my father and son who are both in heaven and have taken a large part of my heart with them. I hope to make them all proud.

|

Key Term |

Definition |

Source |

|

Abuse |

Harm or threatened harm to an adult’s health or welfare caused by another person. Abuse may be physical, sexual or emotional. |

(State of Michigan, 2019) |

|

Aging Shock |

The uncovered cost of prescriptions drugs, medical care not paid by Medicare or their private insurance and the actual cost of the private that is expected to pay the gaps that Medicare does not pay and the uncovered costs of long-term care. |

(Knickman & Snell, 2002) |

|

Bereavement |

A form of depression with anxiety symptoms that is a common reaction to the loss of a loved one. It may be accompanied by insomnia, hyperactivity, and other effects. Although bereavement does not necessarily lead to depressive illness, it may be a triggering factor in a person who is otherwise vulnerable to depression. |

Bereavement (2001) |

|

Burnout |

A process involving gradually increasing emotional exhaustion in workers, along with a negative attitude toward clients and reduced commitment to the profession (Maslach, 1993) |

(State of Michigan, 2019) |

|

Compassion Fatigue |

A set of physical and psychological symptoms appearing in social workers who are exposed to client suffering that occurs as a result of traumatizing events such as physical or sexual abuse, combat, domestic violence, or the suicide or unexpected death of a loved one (Figley, 1995). |

(State of Michigan, 2019) |

|

Compassion Stress |

Is the residue of emotional energy from the empathetic response to the client and is the on-going demand for action to relieve the suffering of a client. |

(State of Michigan, 2019)

|

|

Elderly |

Any person that is 65 years of age or older. |

(Niles-Yokum & Wagner,2015) |

|

Empathetic Response |

Is the extent to which the psychotherapist makes an effort to reduce the suffering of the sufferer through empathetic understanding. |

(State of Michigan, 2019)

|

|

Exploitation |

Misuse of an adult’s funds, property, or personal dignity by another person. |

(State of Michigan, 2019) |

|

Exposure to the Client |

Is experiencing the emotional energy of the suffering of clients through direct exposure. |

(State of Michigan, 2019) |

|

Grief |

A nearly universal pattern of physical and emotional responses to bereavement, separation, or loss. It is time linked and must be differentiated from depression. The physical components are similar to those of fear, hunger, rage, and pain. The emotional components proceed in stages from alarm to disbelief and denial, to anger and guilt, to a search for a source of comfort, and, finally, to adjustment to the loss. |

Grief (2001) |

|

Life Disruption |

Is the unexpected changes in schedule, routine, and managing life responsibilities that demand attention (e.g., illness, changes in life style, social status, or professional or personal responsibilities). |

(State of Michigan, 2019) |

|

Material abuse |

Including theft, fraud, pressure in connection with wills, property or inheritance or financial transactions, or the misuse or misappropriation of property, possessions or benefits. |

(O’Connor & Rowe, 2005, p. 48) |

|

Neglect |

Including the failure of a designated care to meet the needs of a dependent old person, forced isolation from services or supportive networks, or failure to provide access to appropriate health or social care. |

(O’Connor & Rowe, 2005, p. 48) |

|

Physical abuse |

Including physical harm or injury, physical coercion and physical restraint |

(O’Connor & Rowe, 2005, p. 48) |

|

Prolonged Exposure |

Is the ongoing sense of responsibility for the care of the suffering, over a protracted period of time. |

(State of Michigan, 2019) |

|

Psychological abuse |

Including emotional abuse, threats of harm or abandonment, deprivation of contact, humiliation and verbal abuse. |

(O’Connor & Rowe, 2005, p. 48) |

|

Sexual Abuse |

including rape, sexual assault or sexual acts to which the vulnerable older adult has not consented, could not consent, or was pressured into consenting. |

(O’Connor & Rowe, 2005, p. 48)

|

|

Stigma |

A mark of shame or disgrace. A strain. |

(Merriam-Webster, 2019) |

|

Self-care |

Promote specific outcomes such as a “sense of subjective well-being”. |

(Lee & Miller, 2013, p. 97) |

|

Senescence |

Refers to the aging process, including biological, emotional, intellectual, social, and spiritual changes. |

(Lee & Miller, 2013, p. 97)

|

|

Vulnerable |

A condition in which an adult is unable to protect himself or herself from abuse, neglect, or exploitation because of a mental or physical impairment or advanced age. |

(State of Michigan, 2019) |

Elderly Population Statistics

Prior to the 17th century, statistics show the elderly made up less than 2% of the population in the United States. A male’s life expectancy estimated 30 to 38 years of age due to lack of proper health care, farming accidents’, unhealthy working conditions, war fatalities and lack of proper nutrition. A women’s life expectancy was significantly decreased due to bearing many children and suffering poor medical services during childbirth (Egendorf, 2002). Following World War II, we experienced the fastest growth in population, this generation is known as the baby boomers. This population has now become our highest elderly population and with this significant increase, the influx poses both benefits and challenges to our society (Tice & Perkins, 1996).

Seventy-six million people were born between 1946 and 1964 making this the largest and longest-lived generation in the history of the United States. (Torres-Gil, 1992). This is identified as the baby boomer generation. As a result of the baby boomer generation, the number of Americans aged 65 or older is projected to more than double from 46 million today to over 98 million by 2060, increasing from 15% to 24% (Mather, 2016). As a result of improved healthcare, better working conditions and families choosing to have less children, the life expectancy for a man is now 74 years of age and women’s life expectancy is now 80 years of age (Merck Manual, 2004). This produces many new challenges to our current social structure. Social security and medical costs have increased, including the cost of uncovered expenses of medications and long term care.

Seventy-six million people were born between 1946 and 1964 making this the largest and longest-lived generation in the history of the United States. (Torres-Gil, 1992). This is identified as the baby boomer generation. As a result of the baby boomer generation, the number of Americans aged 65 or older is projected to more than double from 46 million today to over 98 million by 2060, increasing from 15% to 24% (Mather, 2016). As a result of improved healthcare, better working conditions and families choosing to have less children, the life expectancy for a man is now 74 years of age and women’s life expectancy is now 80 years of age (Merck Manual, 2004). This produces many new challenges to our current social structure. Social security and medical costs have increased, including the cost of uncovered expenses of medications and long term care.

Baby boomers have introduced a new lifestyle, building careers, having fewer children and waiting till later in life to have children. It is estimated since this population is not reproducing at a rate much less than historically, the population in the United States will decrease as a result (Colby, S., & Ortman, J., 2014 p.2). The decrease in population will help to stabilize the social structure and medical costs.

Diversity of Population

Populations representing about 16% of the elder population: 8% African American, 5.5% Hispanic, 2.1% Asian-Pacific Islander and less than 1% American Indian and native Alaskan. The majority elder population is comprised of whites, at a rate of 74%. (Older Americans, 2000, p.1). In order to understand the needs and circumstances of the diverse population in the United States, it is important to know the demographics of the clients we are serving. One plan does not fit all solutions. Some fail miserably. The various demographics we must know of the population we attempt to serve include: health, age, work, marital status, sex, sexual orientation, race and culture. Whether they have family support, access to transportation and disposable income. We must establish wants and needs before determining what services and products will be put into place. If we do not understand the needs of the population we are serving, we will likely fail when creating services to help. (ODPHD, 2013).

Populations representing about 16% of the elder population: 8% African American, 5.5% Hispanic, 2.1% Asian-Pacific Islander and less than 1% American Indian and native Alaskan. The majority elder population is comprised of whites, at a rate of 74%. (Older Americans, 2000, p.1). In order to understand the needs and circumstances of the diverse population in the United States, it is important to know the demographics of the clients we are serving. One plan does not fit all solutions. Some fail miserably. The various demographics we must know of the population we attempt to serve include: health, age, work, marital status, sex, sexual orientation, race and culture. Whether they have family support, access to transportation and disposable income. We must establish wants and needs before determining what services and products will be put into place. If we do not understand the needs of the population we are serving, we will likely fail when creating services to help. (ODPHD, 2013).

Stages of Development

“Growing older and dealing with long-term care includes help from many people, family members, friends, medical professionals and practitioners in the community. Sometimes aging is gradual and sometimes it’s abrupt with many bumps and emergencies. As people age, the majority develop at least one health problem resulting in functional decline” (Marak, C. 2016, p 1). Many seniors live healthy, independent lives, without experiencing the stages of decline.

Stage 1: Self Sufficiency. Seniors are more independent and able to manage their own health issues. They may begin to acknowledge what the community has to offer for seniors and determine if their homes may need safety features in the future. But for the present time, the elderly enjoys the sense of accomplishments their independence offers. Programs established to help seniors remain in their own homes are Area Agency on Aging, Senior SAFE Program and Life Alert, to name just a few.

Stage 2: Interdependence. Seniors may begin relying on others such as a partner, older children or friends for assistance. Many seniors view this stage as a time of decline because they are no longer able to accomplish the tasks they once could. This is the stage where help may be brought in to assist with minor tasks on a regular basis. It is also a time when safety and security should be addressed by installing safety bars in the bathtub and hallways, ramps for wheelchairs and walkers and obtaining life alert pendants in the case of a fall or emergency.

Stage 3: Dependency. As the aging process continues, the need for more assistance with activities of daily living (ADL’s) may increase. These activities include bathing, toileting, cooking, and shopping. There may also be a decline in memory or psychological functions. At this stage, the senior may experience more physical ailments and chronic pain. As these conditions advance, it may be necessary to move to a senior facility with the level of care necessary for the senior. More often, the needs can be provided by a caregiver for more advanced care and needs Other medical issues, including increased pain can be managed by the primary care physician. This option can become very costly and as additional care is needed, for the safety and care of the elderly, a move to a facility may be the best option.

Stage 4: Crisis Management. In the event of continued decline, the family may recognize they are unable to continue providing the level of care necessary to keep their loved one safe or manage their needs. In this case, family will make decisions regarding the best options for appropriate care such as seeking constant in-home care by a professional or moving the senior to a facility where the care needs can be met.

Stage 5: End of Life. If the senior is able to remain in the home with sufficient care and pain management, many are able to remain in the home until their demise. If hospice is involved, they assist to manage pain and help the family to deal with complex end-of-life decisions. Many professions such as home health aides, nursing home personnel, hospice providers and care physicians are involved at this stage. If the senior is in a facility or needs to be moved for care during the end of life stage, they will be cared for by professionals in a skilled nursing facility (Marak, C., 2016, p 1).

Elderly will progress through the stages of development differently. Some will live life without pain and suffering and pass easily, while others may suffer Alzheimer’s disease or symptoms of dementia and require the care offered by a memory care facility. As we are all very different and have been exposed to different lifestyles, we will move through these stages, each at our own pace and tolerances (Marak, C. 2016).

Physical Changes

According to Busse, (1989), there may be several meanings to the word “aging”. “As a biologic term, it is used to describe those inherent biologic changes that take place through time and ultimately end with death.” (Busse, 1989 pg. 3-4). This definition is at odds with the process of growth and development. Aging begins the moment a person is born. A baby develops into a child, teen and then an adult. But at some point, the aging process changes. The body begins to decline in function, ultimately leading to death. The term used to describe the beginning decline is called senescence. As aging occurs, the body’s cells age and the organs functioning declines.

- Change in vision is a sign of aging.

- A seniors hearing may also decline, resulting in the need for hearing aids.

- The skin becomes thinner, less elastic, drier and finely wrinkled.

- A elder’s ability to taste and smell may also diminish as they age.

- Bones and joints become less dense and weaker due to the decrease in the body’s ability to absorb calcium. This causes high risk of falls and broken bones.

- The elder loses muscle tissue over time and muscle strength tends to decrease.

- The heart and blood vessels change. The walls of the heart become stiffer and the heart fills with blood more slowly.

- The artery walls become thicker and the blood flow changes.

- The aged lungs may weaken, and the kidneys and urinary tract are often affected by age.

- The most common reported chronic conditions among the elderly are arthritis, high blood pressure, heart disease, hearing loss, problems of bones and tendons, cataracts, chronic sinusitis, diabetes and vision loss. This is a condensed list (Merck Manual of Health and Aging, 2004, pp 7-16).

Cognitive and Emotional Changes

As with the body, the mind is also susceptible to illness. Among the most common challenges facing the elderly are medical conditions that attack the brain, specifically the memory. Alzheimer’s disease and dementia are the most common and both directly affect cognition at various levels. Dementia is a general term for loss of memory as well as other mental and physical abilities severe enough to interfere with daily activities. Dementia is not a disease, rather a multitude of symptoms that do not lead to a known disease and is caused by physical changes in the brain. Dementia is common among stroke victims (Mayo Clinic, 1998). There are 9 types of dementia. Alzheimer’s Disease comes in three known forms. Early onset which occurs in those under age 65, usually age 40 to 45, experiencing memory loss and difficulty with daily activities. Late onset occurs in those over 65 years of age and is the most common form of Alzheimer’s disease. The third and most rare form is called Familial Alzheimer’s Disease. It occurs in less than 1% of all cases of Alzheimer’s and is a gene known to exist in at least two generations of the family. (Alzheimer’s and Dementia, 2017). For those suffering Alzheimer’s Disease or dementia, it is not uncommon for them to experience a multitude of behaviors and symptoms. Along with memory loss, a senior suffering Alzheimer’s or dementia may incur loss of communication skills, loss of attention, perceptual problems, depression, agitation, suspiciousness, angry outburst, delusions and hallucinations.

Although depression is a common for those with Alzheimer’s disease and dementia, it is also very common among the elderly in general. Charles M. Schulz, Peanuts author and illustrator provided a scenario that perfectly depicts the emotional pain many feel as indicated by Charlie Brown.

“Charlie Brown was sitting at Lucy’s psychiatric booth. He asked, “Can you cure loneliness?” She replied, “For a nickel I can cure anything.” Charlie Brown then asked, “Can you cure deep down, black, bottom of the well, no hope end of the world, what’s the use loneliness?” Lucy protested, “For the same nickel?!” (Blazer, 1990, p.62-63).

Depression among elderly is a serious condition. Many become depressed due to the decline in their ability to function as they did in early years. Others are fearful of thoughts of end of life, while many suffer severe loneliness as the traditional family unit has changed so drastically over the years. Many lose their spouses and find it difficult to continue on while the severe loneliness and depression sets in. Many elderly men served in wars and suffer Post Traumatic Stress Syndrome.

Suicide is the 8th leading cause of death in the U.S. Persons 65 and older make up 12.5 of the total U.S. population and account for 20.9% of suicides annually. Suicide rates among the elderly increased significantly following the Great Depression, then declined until 1981 through 1987, again increasing from 17 to 20 per 100,000 persons. Among older men, suicide rates increase with age. Among women, the rates are lower at 6.6 per 100,000. Women are more likely to commit suicide at midlife. Although many factors can account for the reasons a senior may consider suicide, such as failing health, lack of independence, loss of spouse, it has been found a relationship between major depressive condition and death by suicide has been identified (Blazer, 1990)

Paranoia, suspiciousness and agitation are common behaviors among elderly. As the memory begins to fail, many elderly people become paranoid and suspicious about things they do not understand or cannot remember. The feeling of not knowing where they are or who the people are around them brings on much anxiety. If the anxiety increases, sudden outbursts often are the outcome of the paranoia or suspiciousness and agitation. When working with people who suffer these behaviors, it is necessary to make them feel safe and validate their thoughts but to also help them understand they do not need to feel fearful or frustrated. It is essential to help the senior feel safe when experiencing these episodes of paranoia, suspiciousness and agitation.

Additional emotional issues are often a result of alcohol abuse by elderly. Alcohol is a depressant and if used long term or abused can lead to more severe depression and many physical issues such as memory loss called alcohol amnesiac disorder which causes difficulty with both short- and long-term memory and an inability to learn new information. This is also identified as one of the 9 types of dementia. (Blazer, 2004).

Often seniors want to feel valued and listened to, especially as they evaluate their life. Oftentimes we deny them the privilege to share with us the knowledge and invaluable presence that we too could offer future generations. The history and knowledge of the elderly is priceless.

Social Change

The elderly struggle with change in their social lives and capabilities. Some have been identified in other sections of this chapter but apply to their involvement in society as well. The most pertinent issues identified by both social workers and the elderly who were questioned provided the following list from (Aging Care, 2019):

-

- Loneliness from losing a spouse and friends

- Inability to independently manage regular activities of living

- Difficulty coping and accepting physical changes of aging

- Frustration with ongoing medical problems and increasing number of medications

- Social isolation as adult children are engaged in their own lives

- Feeling inadequate from the inability to continue to work

- Boredom from retirement and lack of routine activities

- Financial stresses from the loss of regular income

- STD’s are currently on the rise with the senior population

- Younger generation taking advantage of elderly’s vulnerability (Aging Care, 2019)

Spiritual

For most elderly, religion plays a major role in their life, with approximately half attending religious services weekly. “Older adults’ level of religious participation is greater than that in any other age group. For older people, the religious community is the largest source of social support outside of the family and involvement in religious organizations is the most comon type of voluntary social activity” (Kaplin & Berkman, 2019, p.1).

When caring for the elderly, religion and spiritual beliefs often play a significant part in the care provided for the seniors. As the elderly ages and necessary increased care is provided, the elderly may have special wishes in accordance with their religious beliefs or spiritual beliefs. It is essential to know if spirituality or religion are important to the elderly as the beliefs may offer assistance with the elderly coping skills acceptance of their declining health and decreased fear of their final demise (Erichsen & Bussing, 2013, p. 1).

The Stigma of Aging

There are many myths and stigmas that have been associated with elderly population. A myth as defined is, “a usually traditional story of ostensibly historical events that serves to unfold part of the world view of a people or explain a practice, belief, or natural phenomenon” (Merriam-Webster, 2019, p.1). Stigma is defined as, “a mark of shame or discredit” (Merriam-Webster, 2019 p. 1). The term stigmatization is evident in the prevailing of “if I can buy enough pills, cream, and hair, I can avoid becoming old” (Esposito, 1987). Seniors efforts to avoid the uncontrollable outcomes of old age reveal the stigma and negative attitudes associated with advanced age. “Ageism refers to the negative attitudes, stereotypes and behaviors directed toward older adults based solely on their perceived age” (Frankelstein, Burke & Raju, 1995, p.662-663).

Ideally ageism will be replaced by truths. For instance, mental health issues among the elderly can decline with mental health services. Further, older adults are not the victims of deterioration that comes with age but are the survivors of life and the strengths of the elderly must be recognized and celebrated and used as the cornerstone in intervention and prevention services (Zastrow, 1993). The way a senior ages depends on several factors including their lifestyle choices, culture they live in, as well as their supports (Thornton, 2002). This is a bulleted list as follows of different myths and stigmas that have been negatively associated with the elderly population.

The following is a list of negative stigmas and beliefs about seniors:

- All elderly people are ill or disabled (Thornton, 2002).

- Pain is a normal part of life and the aging process (Ellison, White, & Farrar, 2015).

- Elderly people live boring lives and do not have romantic and sexual relationships.

- Elderly are uneducated or even able to learn as the world is continuously changing around us (Thornton, 2002).

- The elderly people are mentally incompetent and are able to be educated and learn new tasks just as a younger person is able to.

- The elderly people are a financial drain on our medical institution (Zastrow, 1993).

- Barriers to delivering mental services to older people is ageism, the “negative image of and attitudes toward people simply because they are old. (Zastrow, 1993).

The invaluable presence of an elderly person is one that is too often overlooked. Positive attributes and beliefs about the elderly population:

- They provide the social and cultural continuity that holds our communities together.

- Wisdom comes with age and experience. The older generation is also a great storehouse of knowledge and history.

- Like a tree needs its roots for growth and nourishment, a society needs roots to keep it grounded in its traditional values and history.

- Grandparents are often available for babysitting and spending quality time with their grandchildren, teaching values and respect.

- Families who have active, healthy grandparents living nearby have the opportunity to develop strong relationships between the kids and their elderly relatives that can greatly enrich the lives of both generations. They can also provide positive role models for young children who probably have little contact with older adults and may regard aging as something negative and depressing.

- For many seniors, old age is a time to become deeply engaged in their churches, local politics, schools and cultural and community organizations.

- They know how to socialize and treat other people in face-to-face conversations without the need for modern technology.

- Many are more conscious of their diet and their health. They watch what they eat, and exercise in order to stay active.

- Seniors have time for themselves, to vacation, volunteer, take classes and garden, among many other activities they may not have had time to do when raising a family.

- Seniors become active in senior centers and organizations to meet other elderly people for social purposes such as dances, playing cards, bingo and dating (Pitlane Magazine, 2019).

Working with the Elderly

In the field of social work, it is important to be able to work with other disciplines of work including physicians, nurses, nurse assistants, chaplains, dietitians, volunteers, dentists, and other social workers at various agencies. There is a need to have client centered goals and plans of care from all disciplines that work with the client (Wright, Lockyer, Fidler, & Hofmeister, 2007).

|

Discipline |

Role |

Source |

|

Social Worker |

|

(Csikai & Weisenfluh, 2013) (Monroe & DeLoach, 2004) (Reese & Raymer, 2004) |

|

Physician |

|

(Wright, Lockyer, Fidler, & Hofmeister, 2007) |

|

Nurse |

|

(Greene, 1984) |

|

Nursing Assistant |

|

(Huey-Ming, 2004) |

|

Chaplain |

|

(Williams, Wright, Cobb, & Shiels, 2004) |

|

Dietitian |

|

(Kang et al., 2018) |

|

Volunteer Coordinator |

|

(Claxton-Oldfield, & Jones, 2012) |

|

Volunteers |

|

(Ghesquiere et al., 2015) |

Elder Abuse and Neglect

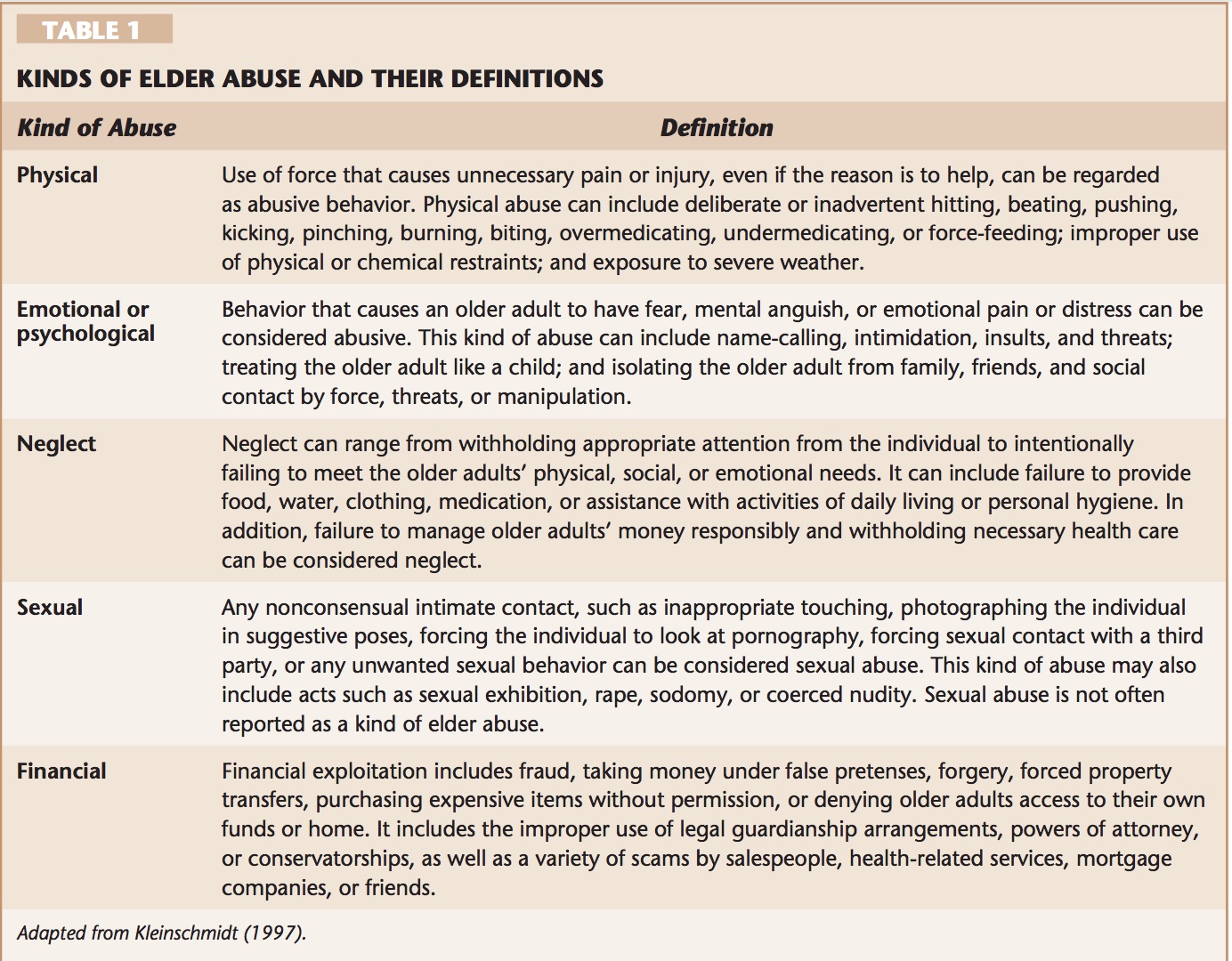

Elder abuse and neglect are under reported in the United States for many reasons including fear and embarrassment by the elderly (O’Connor & Rowe, 2005). Elder victims of abuse risks that include; functional disability, lack of social supports, poor physical health, cognitive impairment, mental health issues, lower social economic status, gender, age, and financial dependence (Pillemar, Burnes, Riffin, & Lachs, 2016). There is an Adult Protective Services (APS) Hotline for reporting a suspected abuse or neglect situation referred to as centralized intake: 855-444-3911 (State of Michigan, 2019). It is important to understand that all social workers are mandated reporters of elder abuse and neglect (State of Michigan, 2019). There is not one specific cause for elderly abuse and neglect. There are many reasons including various dynamics, cultural norms, negligence and lack of education and support (Muehlbauer & Crane, 2006). Potential causes of abuse could be due to mental illness, substance abuse, and the need to abuse from the perpetrator (Pillemar, Burnes, Riffin, & Lachs, 2016). There are several types of abuse defined as follows in Table 1: Kinds of Elder Abuse and their Definitions (Muehlbauer & Crane, 2006, p.44).

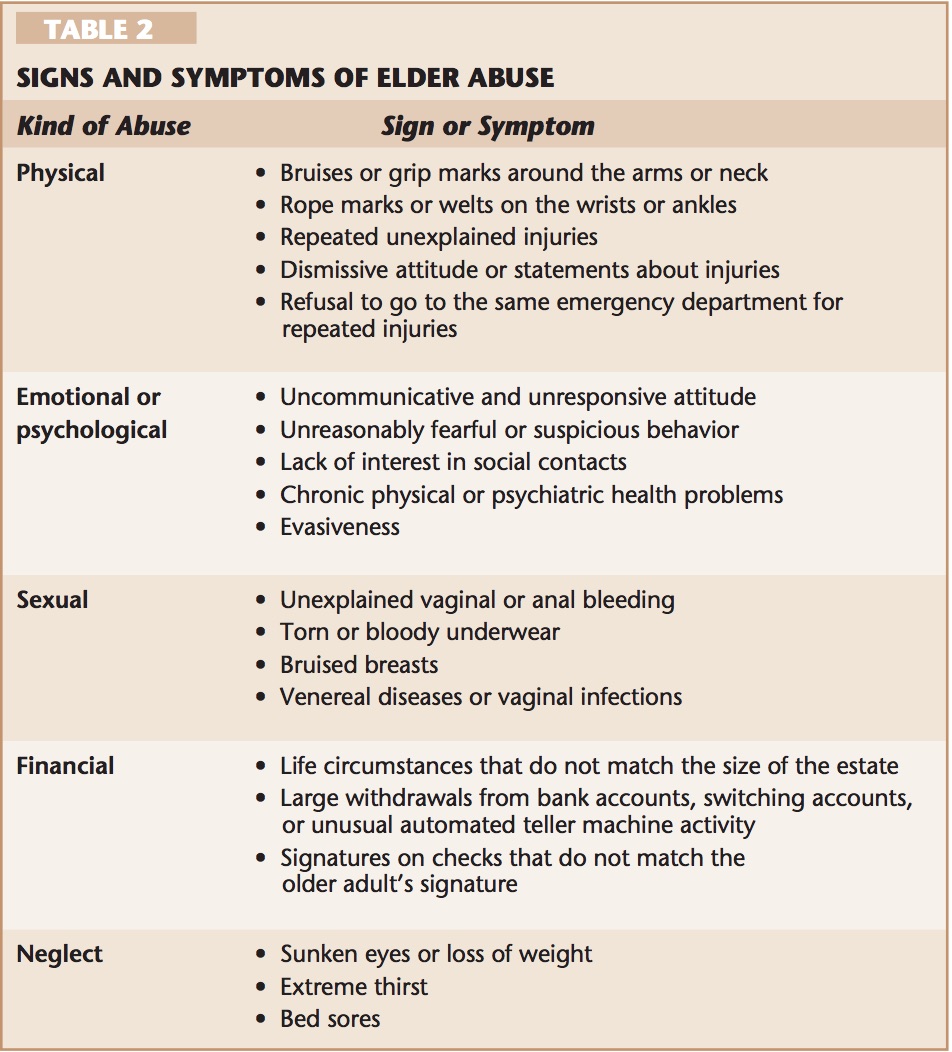

It is important as a social worker to be able to assess the signs and symptoms of elder abuse. It can be difficult to recognize the signs and symptoms of abuse as some elderly are nonverbal and unable to share what is occurring (Muehlbauer & Crane, 2006). Table 2 below lists common signs and symptoms of elder abuse (Muehlbauer & Crane, 2006, p.46).

Adult Protective Services (APS) Case Study: Janice

Janice, a 50 year old women is diagnosed with Schizophrenia and Bipolar Disorder. She was fired from her job as a professor from a University due to not taking her medications and making threats and allegations of a “witch hunt” for her. This client lives alone in a trailer in the middle of the woods. There is no heat or electricity in the home. Several medical professionals have called and reported that she is unable to take care of herself on her own. This client has not been deemed incompetent by two physicians. The APS worker attempts to visit the client and each time is asked to leave the premises. The APS worker noticed some bruises on Janice’s wrists and her arms. The APS worker attempts to address the bruises when Janice says, “Get off my property and never come back or I will call the police!” The APS worker has reported these allegations to her supervisor as well as to the police department. The client has been hospitalized for her medications, but once out of the hospital the client does not continue taking medications. The client is currently not able to pay her bills and the home is in the process of being foreclosed from the client. The bank has reported that there have been several cash withdrawals from the account from ATMs all over the state. The client has refused the APS worker to assist and will not leave the home. The APS worker is unaware of any family or friends of this client in the area. There are also no shelters in the area that will take a client that is non-compliant with taking medications.

- If you were the APS worker, what other resources could you reach out to?

- What would you do to help the client?

- As the APS worker, can you identify any ethical dilemmas, explain?

Medical Care and Insurance

Medicare

Medicare is a supplemental insurance that was created in the U.S. after the Social Security Amendment in 1965 (Rajaram & Bilimoria, 2015). People are eligible for Medicare if they are at least 65 years of age, have end stage renal disease or amyotrophic lateral sclerosis, or have another specific disability (Rajaram & Bilimoria, 2015). There are certain needs that Medicare does not cover including long term skilled nursing facility stays. There are four different sections of Medicare including Part A, Part B, Part C, and Part D (Rajaram & Bilimoria, 2015). This link https://www.ssa.gov/benefits/medicare/ is where a senior can apply for Medicare. Rajaram & Bilimoria (2015) explain the four parts of Medicare as:

Medicare is a supplemental insurance that was created in the U.S. after the Social Security Amendment in 1965 (Rajaram & Bilimoria, 2015). People are eligible for Medicare if they are at least 65 years of age, have end stage renal disease or amyotrophic lateral sclerosis, or have another specific disability (Rajaram & Bilimoria, 2015). There are certain needs that Medicare does not cover including long term skilled nursing facility stays. There are four different sections of Medicare including Part A, Part B, Part C, and Part D (Rajaram & Bilimoria, 2015). This link https://www.ssa.gov/benefits/medicare/ is where a senior can apply for Medicare. Rajaram & Bilimoria (2015) explain the four parts of Medicare as:

|

Part A |

|

|

Part B |

|

|

Part C |

|

|

Part D |

|

Case Study: Jacob

You are working as the social worker for a Commission on Aging agency and one of your clients, Jacob walks into your office. Jacob is an 88-year-old Native American male. He is an U.S. Marine Corps Veteran. Medicare is Jacob’s only insurance. Jacob shares with you that he was unable to purchase his medications last week because the cost is too high with his fixed income of social security.

- What would you do as the social worker to help Jacob?

- What resources do you think could be available for Jacob?

Advanced Directives

As seniors, we have many choices regarding health care and end of life wishes. The Do-Not-Resuscitate orders and Comfort Care Only orders are important for family members who may not know the wishes regarding life sustaining practices. Therefore, if these decisions are made prior and family is made aware , the wishes of the loved one is often carried out with much less stress and ease to both the family and the senior making the decision. If the decision is not made prior to the time it becomes necessary, the loved one may not have the opportunity to have their wishes known. If the DNR or the Advance Directive is not in place, the doctor will make every effort to resuscitate a senior. The Advance Directive and DNR is done in the event an elder is incapacitated to guide decisions about medical treatment.

A Living Will is a document that directs the care in the event of an elderly’s mental incapacitation. A Durable Power of Attorney is a document in which a senior will appoint a person to make decisions in the event they are incapacitated and unable to make the decisions themselves. A Living Will is a document or type of Advance Directive in which a person gives specific directions about treatments that should be following in the event of his or her incapacitation, and usually addresses life-sustaining medical treatment such as removal from life supports, providing food and drink (Pietsch ad Braun, p. 41). Understanding rights as an elderly regarding your wishes for health care is essential as it alleviates much stress for those who would otherwise need to make these decisions. Most seniors have decided under which circumstances they would wish to be resuscitated. It is imperative that each senior make family members or their physician aware of their decisions. Most hospitals will allow these documents to be signed and notarized and filed at the hospital in the event of crisis. It is very important to have documents signed and available for use In the event of an emergency. (Pietsch and Braun, 2000, p. 41).

Placement

In many cases elderly people find they are unable to manage their own care in their homes without some assistance and modifications to their homes for safety purposes. Seniors can make their homes safe by installing ramps, safety bars in bathing areas and widen doorways for walkers and wheel chairs. Oftentimes, the first step taken to keep the elderly in their own home or a family members home, is to hire a caregiver to aid with activities of daily living, medication management and meal preparation. The caregiver will often provide transportation to doctor and dental appointments, errands and any other travel.

https://youtu.be/L0MAZog6IMs

Independent Living Facilities

Many elderly people find that it is either too costly to safely update their own homes or may live in a property with many stairs that are difficult to climb. In the event they need a safer environment, many will seek out independent living facilities where they live in a community of other elderly people where the apartments or homes are built with safety features already I place within the units and where there are many activities and social events specifically designed to help the resident avoid isolation and make new friends. Independent living is typically for those who do not have healthcare needs, but some may need a caregiver to come in and assist with bathing, household chores or to run errands. Many Independent living facilities have a dining room for meals and transportation available for medical appointments and weekly trips to run errands and outing for the residents (National Institute on Aging, 2019).

Assisted Living Facilities

Once care levels increase and the resident is unable to manage their own care without the assistance of daily caregivers, the resident may be encouraged to move to an assisted living facility. Many independent living facilities offer assisted living units on the same property, so the move is minimal. An assisted living level of care, depending on the needs of the senior are often set up to allow one to two to a room, where they may set up their own living areas and meals are often taken in the dining room. The seniors may need assistance ambulating to the dining room resulting in a staff member to assist them with a walker or in a wheel chair. In assisted living facilities, the seniors are usually able to move about the facility without much help, but staff and medical care is available 24/7. There are activities provided for the seniors to encourage them to leave their rooms and engage in social events. Many seniors who move to assisted living facilities state they wish they had moved much sooner as the facilities offers the seniors the opportunity to socialize with others their age and offer a plethora of activities and day trips that seniors who remain in their own homes may have been missing out on. It is not uncommon for family members to take their loved ones out for outside medical appointments, such as dental, medical tests not performed on site and family time. Some seniors are able to be checked out for a night or two in order to spend time with family. For those families who wish to take their loved one out of town, they may make arrangements with another facility in the town they are visiting to place their loved one in an assisted living facility, so as not to interrupt their care, but to allow the senior to continue to be part of the family actives. This is all coordinated with both assisted living facilities prior to travel (Caregivers Library).

Adult Group Homes

Another option for the elderly who are unable to socialize and ambulate, but do not need the level of care of skilled nursing, a group home might be an option for them. The social activities are limited, and the level of care is more individualized with 24/7 care and generally only 10 to 20 seniors living in the home at any given time. All transportation is generally offered, and meals are served family style with all seniors eating together. Many of the seniors in elderly group homes are unable to participate in social activates or engage in extensive conversation. This option is generally utilized once they are unable to manage to ambulate in the assisted living facility and has deteriorated to a high level of care but are not yet bed bound . Many senior can remain in the group home until end of life with hospice care. Some group homes offer “field trips” such as color tours and outings to see the holiday lights. These trips are short, and the seniors generally do not leave the bus (National Institute on Aging, 2019).

Skilled Nursing Facilities

Skilled nursing facilities, often referred to as nursing homes are designed for those who need constant care and are unable to ambulate or perform any of their own ADL’s. This is often the final placement prior to their death. Many suffer significant illness or have been deemed unsafe and unable to be provided the level of care in any offer type of facility. Meals are provided to the residents in their rooms where they do not need to leave their beds. For those who can ambulate but need extensive medical care, there is often limited social activities for them. They may meet in common areas to socialize but rarely do they leave the facility unless a family member checks them out for the day (Caregivers Library).

Memory care facilities are also essential for the elderly who suffer Alzheimer’s disease or dementia. These are often locked wings of assisted living facilities or locked group homes. The care is specialized and considered high level of care as the senior often cannot remember how to toilet themselves, dress, eat by themselves or shower. They need 24/7 care and are a risk for wandering which is the purpose of a locked facility (National Institute on Aging, 2019).

Elderly and the Community

As has been indicated in the above portion of this chapter, the elderly struggle with a variety of issues. But in accordance with their integration and acceptance in the community, various conditions of each community may make a difference in the severity of struggles they endure. Some communities are much more understanding of the needs of their elderly residents and provide social outlets for them. They also redesign their public areas with the elder’s needs in mind and utilize the experiences and intelligence of this population. This is often found in smaller upscale towns where the elderly population is high, and their needs are heard.

For those living in low income or medium income areas in their own homes, many live in areas where the lifestyle is fast paced, transportation is limited to local buses or trains and businesses do not cater to the elderly. Many times, the elderly become victims due to their vulnerability and inability to keep up. Society as a whole tends to have little patience for the aged. They are concerned for their own time and space; they often miss the opportunities they could take to assist someone in need. Understanding that we will all be old one day and know how it feels to be left behind (Merck Manual of Health and Aging, 2004), should keep us all humble and aware of the needs of the older population.

There are many organizations available for elders in need of services. Both public and private social service agencies can either provide services or will have social workers to help locate the appropriate resources for the elderly.

Some agencies included, but are not limited to:

- American Association of Retired Persons

- Area on Aging

- Rotary Club

- Veterans organizations

- Masonic Orders

- United Way

- AARP

- Salvation Army

These are only a few and many more may be available to those living in larger cities (Phillips and Roman, 1984, p. 105-108).

Video shows people laughing (Closed Caption)

The History of Hospice Care

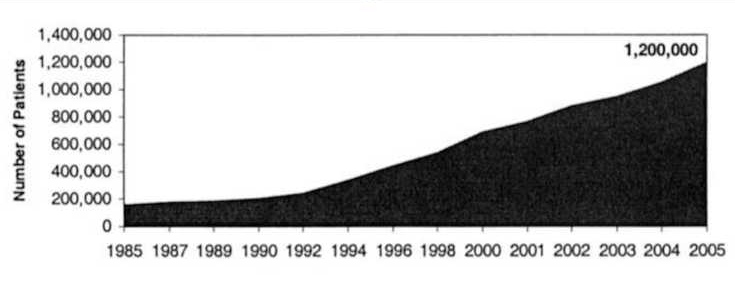

The original concept of hospice care comes from England and has become more popular in the United States (Holden, 1980). There are over three thousand hospices within the United States (Monroe & DeLoach, 2004). Hospice has continued to evolve and develop and has been integrated into the health care system (Monroe & DeLoach, 2004). The concept of hospice started when physician, Dame Saunders, worked with dying clients in 1948. Saunder’s work inspired the creation of St Christopher’s Hospice in 1967 (National Hospice and Palliative Care Organization, 2016). Hospice was established in the United States in 1974 in Connecticut (National Hospice and Palliative Care Organization, 2016). It took a while to progress with hospice and achieve the hospice benefit through Medicaid in Tax Equity and Fiscal Responsibility Act of 1982. Then in 1984, “JCAHO initiated hospice accreditation” (National Hospice and Palliative Care Organization, 2016) Once the Medicare Hospice Benefit (MHB) was created in 1982, hospice care began to become more popular in the United States. Specifically, in 2005 when hospice care clients reached 1.2 million people. (Connor, 2008) As displayed in the chart below by Connor (2008):

As found by National Hospice and Palliative Care Organization (2015) there needs to be two physicians that give a senior a life limiting diagnosis of 6 months or less. Clients can be on hospice at any place that they are comfortable being. The National Hospice and Palliative Care Organization (2018) asserted:

Hospice services can be provided to a terminally ill person wherever they live. This means a client living in a nursing facility or long-term care facility can receive specialized visits from hospice nurses, home health aides, chaplains, social workers, and volunteers, in addition to other care and services provided by the nursing facility. The hospice and the nursing home will have a written agreement in place in order for the hospice to serve residents of the facility (p.1).

There are for-profit, and non-profit hospices (Hospice Analytics, 2018). Hospice care has turned into a competition among hospices to give the best quality of care to the clients. There is a great benefit to having many different options for hospice care. It allows the client to have more control over their end of life decisions. There are more than 5,000 hospices in the United states. The hospices participate in the Medicare program, the first program began in 1974 and has expanded significantly since then across the United States (Fine, 2018). Hospice is growing as the baby boomer generation is aging, in 2020 it is predicted that 20 percent of the population will be elderly in the United States (Niles-Yokum & Wagner,2015).

Hospice Care

Hospice allows clients to be in the comfort of their homes and not be in a hospital environment. As stated by Holden (1980), “High person, low technology” is a good phrase to explain the idea of getting rid of all the hospital equipment and make the client more comfortable (Holden, 1980). Hospice care is not about dying; it is about living and having a good quality of life with celebration. Having an interdisciplinary team implies that all the needs are being met for the client both spiritually, emotionally, and physically (McPhee, Arcand, & MacDonald, 1979). An interdisciplinary team is a group made up of the “physicians, nurses, social workers, chaplains, physiotherapists, dietitians, and volunteers” (McPhee, Arcand, MacDonald, 1979, p.1).

Hospice care is a valuable resource for those near the end of life. It can be a great resource for clients regardless of where their home is. It is beneficial for the clients in nursing homes because they get more professional care experts to a client (Amar, 1994).

National Hospice and Palliative Care Organization (2018) states the following:

Hospice care is available ‘on-call’ after the administrative office has closed, seven days a week, 24 hours a day. Most hospices have nurses available to respond to a call for help within minutes, if necessary. Some hospice programs have chaplains and social workers on call as well (p.1). Both the social worker and nurse are suggested to be present for family at the time of death to offer support to family members and answer questions (Donovan, 1984).

Differences between Palliative Care and Hospice Care

|

Palliative Care |

|

| Hospice Care |

|

| Both |

|

Barriers to Hospice Care

Hospice can be a very difficult discussion and it can be challenging to bring this up to loved ones or a professional hospice staff member. This can be prevented by having the discussion earlier on before the last stages of life (National Hospice and Palliative Care Organization, 2018). Most people have little education on what hospice can offer and what the mission, values, and goals are (Cagle et al., 2015).

Many hospice clients have a great deal of pain. One of the barriers of hospice care is the controversial topic of opioid usage for pain particularly in older adults (Spitz, Moore, Papaleontiou, Granieri, Turner, & Reid, 2011). There are drugs that cause sedation to help with restlessness and pain. However, the ethical issue becomes whether it is better to allow the client to be in pain and able to communicate and eat on their own (Dean, Miller, & Woodwark, 2014). There are barriers to finding appropriate medications for pain management (Cagle et al.,2015). There is a concern about addiction, dependence, and abuse of the medications (Spitz et al., 2011). A fear that the opioids may not reach the client due to unethical doing by a caregiver is another reason to refuse opioid distribution (Spitz et al., 2011). Many physicians are hesitant to distribute opioids and look for alternatives to pain management for clients such as massage therapy (Spitz et al., 2011).

There are negative stigmas that have been associated with hospice and the end of life process. An idea to have a longer stay on hospice by using hospice to treat conditions that could not be stabilized while being at home (McPhee, Arcand, MacDonald, 1979). There is the stigma attached with hospice that is a form of giving up. There are false perceptions that taking medications makes a senior a drug addict or weak for needing pain management control (Cagle et al., 2015).

Hospice clients may feel suicidal and depressed due to the fact they are near the end stages of life (Fine, 2001). Some agencies may monitor the length of visits, which can cause clients not to get the best care or feel as though they were engaged in an appropriate amount of time needed for a life review intervention (Csikai & Weisenfluh, 2013).

It could be very difficult knowing that your lifespan has 6 months or less to be lived. Some clients feel they have unfinished business to attend to. There is a primal fear of death. It may or may not been an unexpected diagnosis (Kumar, D’Souza, & Sisodia, 2013). Some elderly may be living a normal life and suddenly have pain. Once going to a doctor for a checkup, a client may be given an untreatable life-threatening diagnosis. However, some clients may be sick for a long time and not be afraid of dying and be completely at peace with the dying process. Suicidal ideation is common among hospice clients and it is important address why a client is having suicidal feelings.

Barriers are specifically formed when members of the interdisciplinary team do not collaborate appropriately prior to client care (Donovan, 1984). This causes a ripple effect for the client ’s care. There are barriers with the services and resources available to the care team depending on the area. There may be resources available for client benefit in rural compared to urban areas.

Barriers can be very challenging to work through. It is critical to work with the team, which includes: a social worker, nurses, nurse aides, medical director, volunteer coordinator, music therapists, chaplains, and volunteers to brainstorm solutions to these barriers. Education is a good way to help people understand various aspects of social work that many have been mis conceptualized.

Ethical Considerations in Hospice Care

There are ethical dilemmas in all aspects of social work. Csikai (2004) asserted, “During this process hospital social workers may encounter ethical dilemmas regarding quality-of-life, privacy, and confidentiality, interpersonal conflicts, disclosure and truth telling, value conflicts, rationing of health care, and treatment options” (Csikai, 2004, p.1). Euthanasia and assisted suicide are also ethical dilemmas that comes up in conversations with clients on occasion (Csikai, 2004). People have seen this as a legal option in some states and staff struggle with this because it is not legal in all states to practice even when that is the client ’s wish (Csikai, 2004).

Ethical Dilemmas in End of Life Care

It is important to talk about ethical dilemmas when needed and many refer to ethical committees or to their interdisciplinary teams (Csikai, 2004). In the National Association of Social Work (NASW) Code of Ethics to empower a client and give them control. It is mentioned in the NASW Code of Ethics the importance for social workers to promote self-determination under the value of dignity and worth of a person. However, the social work field is not black and white; this causes a struggle when a clinician has to decide if a client is competent to make a decision(Ganzini, Harvath, Jackson, Goy, Miller, & Delorit, 2002). Many ethical dilemmas occur daily and hospice staff must address concerns with their supervisors or managers as needed to give the client the best outcome (Fine, 2001, p.131).Here are some examples of ethical dillemmas as follows in chart below.

- There is worry that the motives for suicide may not just be about the quality of life, but related to finances, feeling like a bother, and other ethical issues (Ganzini et al., 2002).

- There are concerns with the opioid epidemic and risks for abuse and addiction of drugs (Csikai, 2004).

- Is the client is safe in their own home? A client may be at risk of falling while alone, but if they are competent, they can choose to live alone in unsafe environments (Wilson, Gott, & Ingleton, 2011).

- Clinicians should assess for the risk of suicide in all client s who are depressed (Fine, 2001, p.131).

Death and Dying

There are several signs and symptoms that are common during the last few months of a client ’s life. Some of the symptoms include respiratory issues, skin irritations, weakness, swelling, restlessness, confusion, and fatigue (Kehl & Kowalkowski, 2012). There is always a chance that a client may not experience these symptoms at all during the last few days of a client’s life (Kehl & Kowalkowski, 2012). During the last few weeks hospice staff may refer to the client as “transitioning” meaning they are nearing the end of life (Kehl & Kowalkowski, 2012). Donovan (1984) explained, the social worker has a vital role within the hospice team. The social worker helps the client and family with funeral arrangements, financial assistance, resources, and support. Life review is one intervention that does reduce physical pain and depressive symptoms, improving the client’s quality of life (Csikai & Weisenfluh, 2013).

The social worker and the nurse work hand and hand with the client. Both the social worker and nurse are suggested to be present for family at the time of death to offer support to family members and answer questions (Donovan, 1984). The social worker should be present throughout the client’s journey through hospice to help with any issues that may arise (Reese & Raymer, 2004). Monroe & DeLoach explained, “The hospice social worker also makes clinical assessments, provides referrals, facilitates discharge planning, ensures continuity of care, serves as an advocate, offers crisis intervention, and serves as a counselor” (Monroe & DeLoach, 2004).

Grief and Loss

Every person will experience grief differently and will have various bereavement risk levels depending on the person and situation. As the social worker you will complete a bereavement risk assessment based on a specific scale. Most people will be able to function and return to their daily life activities following acute grief process. However, some may develop a mental health diagnosis because the grief may influence a person’s ability to function in their daily lives (Ghesquiere, Aldridge, Johnson-Hürzeler, Kaplan, Bruce, & Bradley, 2015). If grief becomes severe and is left untreated or assessed it may lead to thoughts of suicide or even suicide (Ghesquiere et al., 2015). The social worker should do a bereavement assessment and this information should be distributed to the entire hospice care team especially the Bereavement Coordinator (Ghesquiere et al., 2015). There are different types of grief such as normal grief, anticipatory grief, and complicated grief.

|

Normal Grief

|

|

|

Anticipatory Grief

|

|

|

Complicated Grief

|

|

Self Care and Social Work

There is a need to practice self-care as it has shown to be beneficial to an elder’s health and resilience (Lee & Miller, 2013). There has been a link between effective self-care and being able to cope with stress and traumatic situations. Self-care can help a social worker become a better advocate and have a life long career in social work (Lee & Miller, 2013). Social work leaders recognize the seriousness of the consequences of work-related fatigue, stress and compassion fatigue. “Figley (1995) coined the term Psychological symptoms of this type of secondary traumatic stress include depression, anxiety, fear, rage, shame, emotional numbing, cynicism, suspiciousness, poor self-esteem, and intrusive thoughts or avoidance of reminders about client trauma”. Physiological symptoms include hypertension, sleep disturbances, serious illness and a relatively high mortality rate in helping professionals (Beaton & Murphy, 1995).

Burnout has been an ongoing issue with workers in the human service field. It is a gradual emotional exhaustion that may lead to a negative attitude toward clients and reduced commitment to the profession (Maslach, 1993). When the work demand are high with limited rewards and appreciation, burnout occurs at a significantly high rate.

Some effective means of self-care include:

- Practice mindfulness.

- Start a “positivity” file.

- Get up and move.

- Shake up your routine

- Write it down (and throw it away).

- Activate your self-soothing system

- Take time out for yourself

- Work should be left at the office or job site.

Challenges and Strengths

There are difficulties as well as benefits to the aging process and the transition into becoming an elder. One challenge is that of changing needs that affect housing options. Some are forced to move from their home they have lived in their entire life into some type of facility due to not having caregivers or being able to care for themselves (Ellison, White, Farrar, 2015). Many elderly people also have experienced a significant amount of losses in their life including family, friends, a spouse, partners, and even children as they have aged (Ellison, White, Farrar, 2015).

During the aging process doctor visits may multiply, medical costs are rising, which can impact one’s retirement budget. Challenges also include the declining of health that threatens a senior’s day to day activities. Although it is inevitable health issues progress with age, it is important to prepare mentally prior to the occurrence by learning more about coping skills related to health issues. Challenges also include completing simple tasks once easily accomplished but escalating in difficulty as the body ages and weakens. It may become necessary to have a home care provider to assist with daily tasks. The elderly often worry about financial security. Most live on fixed incomes and are unable to afford the comforts of life they used to enjoy. Loneliness is a major concern of the elderly. They are unable to move about as they once did and find socialization difficult due to lack of mobility. Financial predators are those unscrupulous people looking to prey on the vulnerability of senior citizens by trying scare tactics to get them to provide banking information to them or to sell them unnecessary services or goods (Best for Seniors Online, 2019). Other challenges experienced by seniors are abuse and neglect in the nursing homes and assisted living facilities due to under-staffing issues, leading to discontented staff. Transportation and lack of mobility are also challenges of the elderly. They often must rely on others for help getting to doctors’ appointments, grocery shopping or other necessary errands. Likely the hardest hurdle for seniors to manage is the continuous changes in technology that hinders those who are not familiar with current technology (Agency for Health Care Administration, 2013).

Although challenges are experienced by the elderly, many seniors experience positive and healthy benefits as they age. Seniors who believe in themselves and their capabilities, remain active and stay engaged intellectually have a higher probability of a less challenging experience as they age. Also, those who have strong spiritual beliefs often handle adversity due to their resiliency and faith. Focusing on the strengths and encouraging active and healthy lifestyles can make significant improvements in an elder’s health of their body and mind (Merck Manual of Health and Aging, 2004). Seniors have a lifetime of valuable information to pass on to their family and friends. Many still believe a handshake is all that is needed to make an agreement. The elderly tend to hold to their values and beliefs of hard work and honesty. ” By not listening, society is allowing parents, grandparents, and great grandparents to slip away without allowing them the opportunity to teach. As they leave us, we are refusing them the privilege to share with us the knowledge and invaluable presence that we too could one day offer our own children.

The presence of the elderly is worth more than silver and gold, their presence is priceless” (Debate. org, 20).

References

Administration on Aging. (2000). A profile of older Americans: 2000. Retrieved from http://www.aoa.gov/aoa/stats/profile/default.htm

Aging Care. (2019). What are social issues facing the elderly? [discussion board]. Retrieved from https://www.agingcare.com/Discussions/what-are social- issues-facing-the-elderly-191826.htm

Beaton, R.D., & Murphy, S.A. (1995). Working with people in crisis: Research implications. In Charles R. Figley (Ed.), Compassion fatigue: Coping with secondary traumatic stress disorder in those who treat the traumatized. (pp. 74-75). New York: Brunner/Mazel

Baker, E. K. (2003). The concept and value of therapist self-care. In E. K. Baker (Ed.), Caring for ourselves: A therapist’s guide to personal and professional well-being (pp. 13–23). Washington, DC: American Psychological Association. doi:10.1037/10482–001

Beers, M., & Jones, T. (2004). The Merck manual of health and aging (pp. 1-25). New York, NY: Merck Research Laboratories.

Bereavement. (2001). Mosby’s Medical, Nursing, & Allied Health Dictionary. New York, NY: Elsevier. Retrieved from Health Reference Center Academic.

Best for Seniors Online. (2019). 10 challenges elderly people face and wish you understood I. Retrieved from https://bestforseniors.online/problems-elderly-people-have/

Blueprint for the New Millennium (2001). Strengthening the impact of social work to improve the quality of life for older adults & their families [Brochure]. New York, NY: CSWE

Brucato, B., & Neimeyer, G. (2009). Epistemology as a predictor of psychotherapists’ self-care and coping. Journal of Constructivist Psychology, 22(4), 269–282. doi:10.1080/10720530903113805

Busse, E. W. (1989). The myth, history, and science of aging. In E.W. Busse & D. G. Blaze (Eds.), Geriatric Psychiatry (p. 3). Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Press.

Cagle, J., Zimmerman, S., Cohen, L., Porter, L., Hanson, L., & Reed, D. (2015). Empower: An intervention to address barriers to pain management in hospice. Journal of Pain and Symptom Management, 49(1), 1-12. doi:org/10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2014.05.007

Claxton-Oldfield, S., & Jones, R. (2012). Holding on to what you have got: Keeping hospice palliative care volunteers volunteering. American Journal of Hospice & Palliative Medicine, 30(5), 467-472. doi:10.1177/1049909112453643

Colby, S., & Ortman, M. (2014). The baby boom cohort in the United States 2012 to 2060. Current Population Reports. Washington DC: U.S. Census Bureau.

Collins, W. L. (2005). Embracing spirituality as an element of professional self-care. Social Work & Christianity, 32(3), 263–274. Retrieved for Academic Search Complete.

Connor, S. R. (2008). Development of hospice and palliative care in the United States. OMEGA Journal of Death and Dying, 56(1), 89-99. doi:10.2190/om.56.1.h

Csikai, E. L. (2004). Social workers’ participation in the resolution of ethical dilemmas in hospice care. Health & Social Work, 29(1), 67–76. Retrieved from Academic Search Complete.

Csikai, E., & Weisenfluh, S. (2013). Hospice and palliative social workers’ engagement in life review interventions. American Journal of Hospice and Palliative Medicine, 30(3), 257-263. doi:org/10.1177/1049909112449067

Dean, A., Miller, B., & Woodwark, C. (2014). Sedation at the end of life: a hospice’s decision-making practices in the UK. International Journal of Palliative Nursing, 20(10), 474-481. doi:org.10.12968/ijpn.2014.20.10.474

Debate.org, (2019). Do the elderly play an important role in society? Retrieved from: https://www.debate.org/opinions/do-the-elderly-play-an-important-role-in-society

Donovan, J. A. (1984). Team nurse and social worker avoiding role conflict: Paradoxically, conflict in teamwork can be minimized by more overlap of role functions. American Journal of Hospice Care, 1(1), 21–23. doi/abs/10.1177/104990918400100105

Dyeson, T. B. (2004). The home health care social worker: A conduit in the care continuum for older adults. Home Health Care Management & Practice, 16(4), 290–292. doi/abs/10.1177/108482230352533

Egan, K., & Arnold, R. (2003). Grief and bereavement care. The American Journal of Nursing, 103(9), 42-53. doi:161.57.201.14

Ellison, D., White, D., & Farrar, F. (2015). Aging population. Nursing Clinics of North America, 50(1), 185-213. doi:org/10.1016/j.cnur.2014.10.014

Esposito, J.L. (1987). The obsolete self: Philosophical dimensions of aging. Los Angeles, CA: University of California Press.

Federal Interagency Forum on Aging-Related Statistics, (2016). Older Americans 2016: Key Indicators of Well- Being. Federal Interagency Forum on Aging-Related Statistics. Washington, DC: U.S. Government Printing Office.

Figley, C. R. (2002). Compassion fatigue: Psychotherapists chronic lack of self care. Journal of clinical psychology, 58(11), 1433-1441. doi:10.1002/jclp.10090

Figley, C. R. (2015). Compassion fatigue: Coping with Secondary Traumatic Stress Disorder in Those Who Treat the Traumatized. London: Routledge. doi:. 0021-9010/95/J3.00

Fine, R. L. (2001). Depression, anxiety, and delirium in the terminally ill patient. Baylor University Medical Center Proceedings, 14(2), 130-133. doi:10.1080/08998280.2001.11927747

Fung, V., Mangione, C. M., Huang, J., Turk, N., Quiter, E. S., Schmittdiel, J. A., & Hsu, J. (2010). Falling into the coverage gap: Part D drug costs and adherence for medicare advantage prescription drug plan beneficiaries with diabetes. Health Services Research, 45(2), 355-375. doi:10.1111/j.1475-6773.2009.01071.x

Finkelstein, L. M., Burke, M. J., & Raju, M. S. (1995). Age discrimination in simulated employment contexts: An integrative analysis. Journal of Applied Psychology, 80(6), 652-663. doi:10.1037//0021-9010.80.6.652

Ganzini, L., Harvath, T., Jackson, A., Goy, E., Miller, L., & Delorit, M. (2002). Experiences of Oregon nurses and social workers with hospice clients who requested assistance with suicide. The New England Journal of Medicine, 347(8), 582-588. doi:10.1056/NEJMsa020562

Gandhi, S. (2012). Differences between non-profit and for-profit hospices: Client selection and quality. International Journal of Health Care Finance and Economics, 12(2), 107-127. doi:1 0.1007/s10754-02-9109-y

Ghesquiere, A., Aldridge, M., Johnson-Hürzeler, R., Kaplan, D., Bruce, M., & Bradley, E. (2015). Hospice services for complicated grief and depression: results from a national survey. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society, 63(10), 2173-2180. doi.org/10.1111/jgs.13656

Greene, P. E. (1984). The pivotal role of the nurse in hospice care. CA: A Cancer Journal for Clinicians, 34(4), 204-205. doi:10.3322/canjclin.34.4.204

Grief. (2001). Mosby’s Medical, Nursing, & Allied Health Dictionary. New York, NY: Elsevier. Retrieved from Health Reference Center Academic.

Holden, C. (1980). The hospice movement and its implications. The ANNALS of the American Academy of Political and Social Science, 447(1), 59-63. doi:10.1177/000271628044700108

Hospice Analytics. (2018). In house hospice solutions. Retrieved from http://www.nationalhospicelocator.com/hospices/michigan

Huey-Ming, T. (2004). Roles of nurse aides and family members in acute patient care in Taiwan. Journal of Nursing Care Quality, 19(2), 169-175. doi:10.1097/00001786-200404000-00015

Jordan, K. (2010). Vicarious trauma: Proposed factors that impact clinicians. Journal of Family Psychotherapy, 21(4), 225-237. doi.org/10.1080/08975353.2010.529003

Kang, H., Yang, Y., Park, J., Heo, G., Hong, J., & Kim, H. (2018). Nutrition intervention through interdisciplinary medical treatment in hospice clients: From admission to death. Clinical Nutrition Research, 146-152. doi:10.7762/cnr.2018.7.2.146

Kaplin, D. & Berkman, B., (2014). Religion and spirituality in older adults. Kenilworth, NJ: Merck Manual.

Kehl, K., & Kowalkowski, J. (2012). A systematic review of the prevalence of signs of impending death and symptoms in the last 2 weeks of life. American Journal of Hospice & Palliative Medicine. doi:10.1177/1049909112468222

Knickman, J., & Snell, E., (2002). The 2030 problem: Caring for aging baby boomers. HSR health service research, PMC U.S. National Library of Medicine, National Institute of Health. doi:10.1034/j.1600-0560.2002.56x

Kumar, S. P., D’Souza, M., & Sisodia, V. (2013). Healthcare professionals’ fear of death and dying: implications for palliative care. Indian Journal of Palliative Care, 19(3), 196–198. doi:10.4103/0973-1075.121544

Lee, J., & Miller, S. (2013). A self-care framework for social workers: Building a strong foundation for practice. The Journal of Contemporary SocialServices, 94(2), 96-103. doi:10.1606/1044-3894.4289

Marak, C., (2016). Iris: Understanding the 5 stages of life. Retrieved from: https://www.iris.xyz/solutions/aging/understanding-the-5-stages-of-aging-from-self-sufficiency-to-end-of-life

Maslach, C. (1993). Burnout: A multidimensional perspective. In Schaufeli, W., Maslach, C., & Marek, T. (Eds.), Professional burnout: Recent developments in theory and research (pp. 1-10). Philadelphia, PA: Taylor & Francis.

Mather, M. (2016). Fact sheet: Aging in the United States. population reference bureau.

Mayo Foundation for Medical Education and Research (MFMER). (2019). Dementia. Retrieved from Retrieved from https://www.mayoclinic.org/diseases-conditions/dementia/symptoms-causes/syc-20352013

McPhee, M. S., Arcand, R., & MacDonald, R. N. (1979). Taking the stigma out of hospice care: Flexible approaches for the terminally ill. Canadian Medical Association Journal, 120(10), 1284–1288.

Merriam-Webster. (2019). Myth. Retrieved from https://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/myth

Merriam-Webster. (2019). Stigma. Retrieved from https://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/stigma

Michigan Department of Health and Human Services. (2019). Adult protective services. Retrieved from https://www.michigan.gov/mdhhs/0,5885,7-339-73971_7119_50647—,00.html

Monroe, J., & DeLoach, R. J. (2004). Job satisfaction: How do social workers fare with other interdisciplinary team members in hospice settings? OMEGA – Journal of Death and Dying, 49(4), 327–346. https://doi.org/10.2190/J9FD-V6P8-GCMJ-HFE0

Muehlbauer, P., & Crane, P. (2006). Elder abuse and neglect. Journal of Psychosocial Nursing and Mental Health Services,44(11), 43-48. Retrieved from PubMed database

National Caregivers Library. (2019). Types of care facilities. Retrieved from www.caregiverslibrary.org/caregivers-resources/grp-care-facilities/types-of-carefacilities-article.aspx

National Hospice and Palliative Care Organization. (2009). NHPCO facts and figures: Hospice care in America. Retrieved from http://www.halcyonhospice.org/DL/NHPCO_facts_and_figures 2009.pdf

National Hospice and Palliative Care Organization. (2015). The medicare hospice benefit. Retrieved from www.hospiceactionnetwork.org

National Hospice and Palliative Care Organization. (2016). History of hospice care. Retrieved from https://www.nhpco.org/history-hospice-care

National Hospice and Palliative Care Organization. (2018). Hospice FAQs. Retrieved from https://www.nhpco.org/about-hospice-and-palliative-care/hospice-faqs

Niles-Yokum, K., & Wagner, D. L. (2015). The aging networks: A guide to programs and services (9th ed.). New York, NY: Springer Publishing Company.

Office of Disease Prevention and Health Promotion, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, (2013). Diversity among older adults requires diverse solutions. Retrieved from https//health.gov/news/blog/2013/07/diversity-among-older-adults/.

O’Connor, K., & Rowe, J. (2005). Elder abuse. Reviews in Clinical Gerontology, 15(1), 47-54. doi:10.1017/S0959259805001668

Pietsch, J. H., & Braun, K. L. (2000). Cultural issues in end of life decision making. London: Sage.

Pillemar, K., Burnes, D., Riffin, C., & Lachs, M. (2016). Elder abuse: global situation, risk factors, and prevention strategies. The Gerontologist, 56(S2), S194-S205.

Phillips, A. H., & Roman, C. K. (1984). A practical guide to independent living for older people. Seattle, WA: Pacific Search Press.

Pomeroy, E. C. (2011). On grief and loss. Social Work 56(2), 101-105. doi:org.10.1093/sw/56.2.101

Rajaram, R., & Bilimoria, K. (2015). Medicare. JAMA, 314(4). doi:10.1001/jama.2015.8049

Reese, D., & Raymer, M. (2004). Relationships between social work involvement and hospice outcomes: Results of the national hospice social work survey. Social Work, 49(3), 415-422. Retrieved from Health Reference Center Academic.

Richards, K. C., Campenni, C. E., & Muse-Burke, J. (2010). Self-care and well-being in mental health professionals: The mediating effects of self-awareness and mindfulness. Journal of Mental Health Counseling, 32(3), 247–264.

Spitz, A., Moore, A. A., Papaleontiou, M., Granieri, E., Turner, B. J., & Reid, M. C. (2011). Primary care providers perspective on prescribing opioids to older adults with chronic non-cancer pain: A qualitative study. BMC Geriatrics,11(1). doi:10.1186/1471-2318-11-35

Stebnicki, M. A. (2007). Empathy fatigue: Healing the mind, body, and spirit of professional counselors. American Journal of Psychiatric Rehabilitation, 10(4), 317–338. doi:10.1080/15487760701680570

Thornton, J. E. (2002). Myths of aging or ageist stereotypes. Educational Gerontology, 28(4) 301–312. https://doi.org/10.1080/036012702753590415

U.S. National Library of Medicine. (2018). What is palliative care?: Medline Plus Medical Encyclopedia. Retrieved from https://medlineplus.gov/ency/client instructions/000536.htm

Watcherman, M., Marcantonio, E., Davis, R., & McCarthy, E. (2011). Association of hospice agency profit status with patient diagnosis, location of care, and length of stay. JAMA, 305(5), 472-479. doi:10.1001/jama.2011.70.

Williams, M., Wright, M., Cobb, M., & Shiels, C. (2004). A prospective study of the roles, responsibilities and stresses of chaplains working within a hospice. Palliative Medicine,18(7), 638-645. doi:10.1191/0269216304pm929oa

Wilson, F., Gott, M., & Ingleton, C. (2011). Perceived risks around choice and decision making at end-of-life: A literature review. Palliative Medicine, 27(1), 38-53. doi:10.1177/0269216311424632

Wright, B., Lockyer, J., Fidler, H., & Hofmeister, M. (2007). Roles and responsibilities of family physicians on geriatric health care teams: Health care team members’ perspectives. Canadian Family Physician Medecin De Famille Canadien,53(11), 1954-1955. Retrieved from PubMed.

Zastrow, C., (1993). Introduction to social work and social welfare. Pacific Grove, CA: Brooks/Cole Publishing

Licenses and Attributions

Open Content, Shared Previously

Aging Population -Emma and Kim Capstone Document by Emma Rutkowski , Kimberly Bomar, and and Ferris State University Department of Social Work, Introduction to Social Work at Ferris State University is licensed under CC BY 4.0.