2 Generalist Practice

Aikia Fricke; Ferris State University Department of Social Work; and Elizabeth B. Pearce

About the Author:

My Name is Aikia Fricke, I currently work for Community Mental Health for Central Michigan. I have worked with this agency since 2008, working as a clubhouse advocate, case manager, and most recently as an employment specialist. I obtained my BSW at Ferris State University in 2006, and I am currently an MSW candidate at Ferris State University. I am a full-time mother to four lovely children and a full-time wife to a wonderful and very supportive husband, as without his tremendous support furthering my education would not have been possible. I hope that you find this chapter interesting, informative, and helpful as many of you began your journey into the field of social work.

Generalist Practice

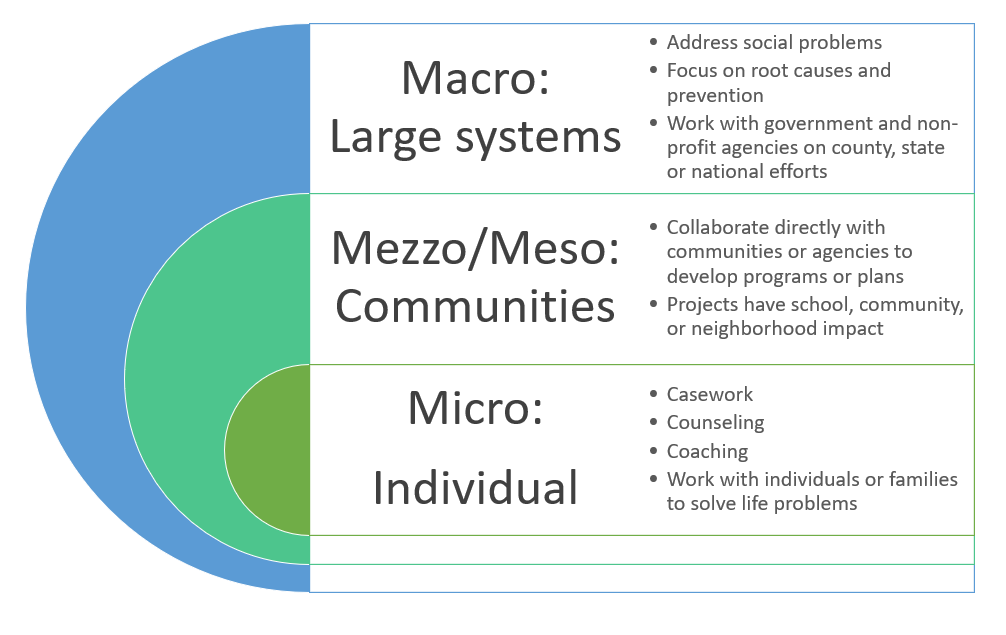

When looking at generalist practice primary theories, the first question that may come to mind is what is generalist practice? Generalist practice introduces students to the basic concepts of promoting human well-being and applying preventative and intervention methods to social problems at individual (micro), group (mezzo), and community (macro) levels while following ethical principles and critical thinking (Inderbitzen, 2014).

A generalist in a helping profession uses a wide range of prevention, intervention, and remediation methods when working with families, groups, individuals, and communities to promote human and social well-being (Johnson & Yanca, 2010).

Being a generalist practitioner prepares you to enter nearly any profession within the human services and social work fields, depending on your population of interest (Inderbitzen, 2014).

Micro, Mezzo, Macro Levels of Problem-Solving

Micro level practice is the most common practice scenario and happens directly with an individual client or family; in most cases this is considered to be case management and therapy service. Micro level work involves meeting with individuals, families or small groups to help identify, and manage emotional, social, financial, or mental challenges, such as helping individuals to find appropriate housing, health care, and social services. Micro-practice may even include helping military officials and families cope with military life and circumstances helping with school related resources, or working with clients around substance use, homelessness, or food insecurity.

The focus of micro level practice is to help individuals, families, and small groups by giving one on one support and provide skills to help manage challenges (Johnson & Yanca. 2010).

Mezzo (aka meso) level practice involves developing and implementing plans with communities such as neighborhoods, places of worship, and schools. Professionals interact directly with people and agencies that share the same passion , interest, location, or challenge. The big difference between micro and mezzo level social work is that instead of engaging in individual counseling and support, mezzo practitioners help groups of people. Human Service professionals might help establish a free food pantry within a local place of worship, health clinics to provide services for the uninsured, or community budgeting/financial programs for low income families.

Macro level practice is similar to mezzo practice in that both tend to address social problems. But the macro practice is on a larger and less direct scale and often with a preventative approach. The responsibilities on a macro level typically are finding the root cause, the why, and the effects of citywide, state, and/or national social problems. Awareness of systems of privilege and oppression are foundational to this work.

Professionals are responsible for creation and implementation of human service programs to address large scale social problems. Macro level social workers often advocate to encourage state and federal governments to change policies to better serve vulnerable populations (Kirst-Ashman & Hull, 2015). They may be employed at non-profit organizations, public defense law firms , government departments, and human rights organizations.While macro human services or social workers typically do not provide therapy or other assistance (case management) to clients, they may interact directly with the individuals while conducting interviews if they are doing research that pertains to the populations and social inequalities of their interest.

The human services and social work professions are broad and allow practitioners to move within the micro, mezzo, and macro levels. Most begin at the micro level to understand the inequalities, disadvantages, and the needed advocacy for vulnerable populations.

Theories

We will examine the human services field from a variety of theoretical perspectives. A theoretical perspective, or more briefly, a “theory” is not just an idea that someone has. Rather it is a structural framework, explanation, or tool that has been tested and evaluated over time. Theories are developed and utilized via scholarship, research, discussion, and debate. Theories help us to understand the world in general, and in this instance the ways in which families and systems form, function, interact with, and experience the world.

Systems Theory

Systems Theory is an interdisciplinary study of complex systems. It focuses on the dynamics and interactions of people in their environments (Ashman, 2013). The Systems Theory is valuable to helping professions because it focuses on identifying, defining, and addressing problems within social systems.

We utilize the Systems Theory to help us understand the relationships between individuals, families, and organizations within our society. Systems theory helps us to identify how a system functions and how the negative impacts of a system can affect a person, family, organization, and society,. The same information can be used to identify strengths and to cause a positive impact within that system (Flamand, 2017).

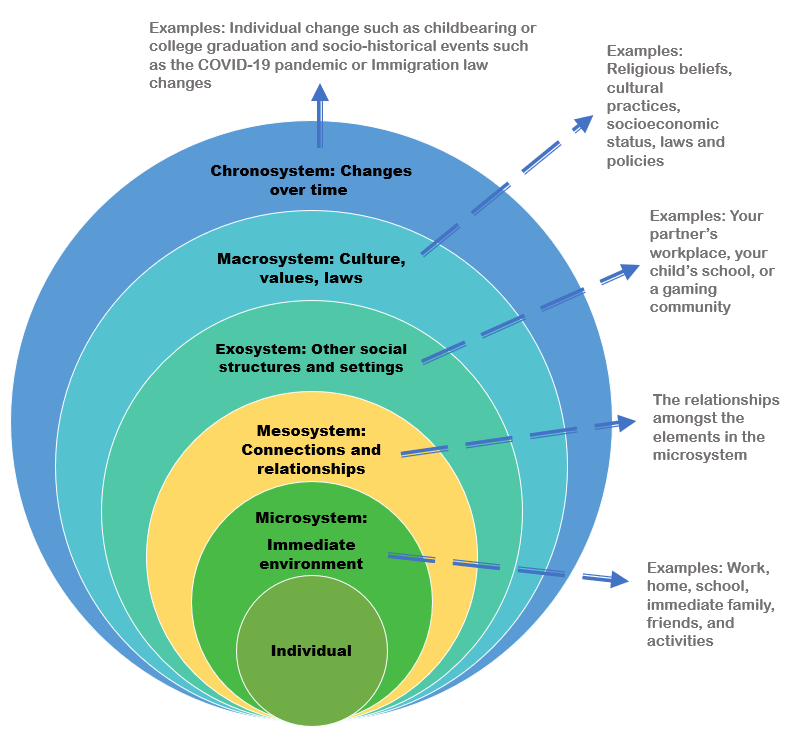

Ecological Systems Theory

The Ecological Systems Theory was created in the late 1970’s by Urie Bronfenbrenner. He developed this theory to explain how environments affect a child’s or individual’s growth and development. The model is typically illustrated with six concentric circles that represent the individual, environments and interactions.

The main concept behind ecological approach is “person in environment” (P.I.E). The ecological approach implies that every person lives in an environment that can affect their outcome or circumstance. In helping professions individuals work to improve a person’s environment by helping them identify what is working well and what is negatively impacting them within their environments.

The microsystem is the smallest system, focusing on the relationship between a person and their direct environment, typically the places and people that the person sees every day often including parents and school for a child or partner, work/school for an adult. The exosystem are the people and places that an individual interacts with on a regular basis but not daily, perhaps a place of worship, club, lesson, or social group. The mesosystem, which lies between the micro and exo systems is representative of how those people and places interact and cooperate. If they work together well, it can have a positive effect on the individual. For example, if a student also has a job, is the employer willing to work around the school schedule? If a child goes to a child care program, do the teacher and the parent communicate clearly with each other? The mesosystem is really important because it is about the relationships and the interactions amongst important environments.

The macrosystem identifies the larger values and attitudes of the culture and varies by location and interest. The chronosystem describes time as a system that affects individuals. Large events and trends such as the dramatic increase in college costs and debt, the COVID-19 pandemic, and the dramatic increase in wildfires on the west coast of the United States are all examples of events in the chronosystem that affect individuals and families in the first part of the 21st century.

Tools: Eco-maps and Genograms

Tools used to understand how systems and environments impact a client include eco-maps and genograms. An eco-map is a diagram that shows the social and personal relationships of an individual with his or her environment. Eco-maps were developed in 1975 by Dr. Ann Hartman, a social worker who is also credited for developing the genogram (Genachte, 2009).

Eco-maps will vary in what they look like as each map will cater to the specific individual or family and will highlight the stressors (negatives), positives, and relationships. The video below addresses what an eco-map is, why it’s important for human services workers, and how it is different from a genogram.

A genogram mimics a family tree. On a family tree each branch represent a family. A genogram digs deeper and identifies relationships, deaths, marriages, births, divorce, and adoptions and other significant family events. When collecting information to complete a genogram it is useful to understand a family’s dynamics (Johnson & Yanca, 2010.)

Genograms can help clients identify their roots and culture. Completing genograms can reopen past trauma or loss. A helping professional needsto be prepared to discuss and address these issues with their clients. The gitmind website rates the best free programs for creating genograms.

Strengths Approach

The Strengths Approach was based on thinking by social worker Bertha Reynolds in the mid-20th century. who wrote several books that emphasized ideas that moved beyond the popular psychoanalytic approach of the time. It was formally developed by a team including Dennis Saleeby, Charles Rapp, and Anne Weick at the University of Kansas. The Strengths Approach emphasizes that

- every person, group, family, and community has strengths; and

- every community or environment is full of resources (Johnson & Yanca, 2010)

In the Strengths Approach, it is the professional’s job to help the client identify their strengths. Sometimes society and individuals are focused on the negative impacts of their lives and have a difficult time identifying the positive aspects of their lives and situations. When using the Strengths Approach not only is the human services professional or social worker helping the client to identify their personal strengths, but the worker is also helping the client identify local resources to help the client needs.

This approach focuses on the strengths and resources that the client already has rather than building on new strengths and resources. The reasoning behind the strength approach is to help clients with immediate needs, to help with finding solutions to immediate problems., and to identify and build strengths to use in the future.

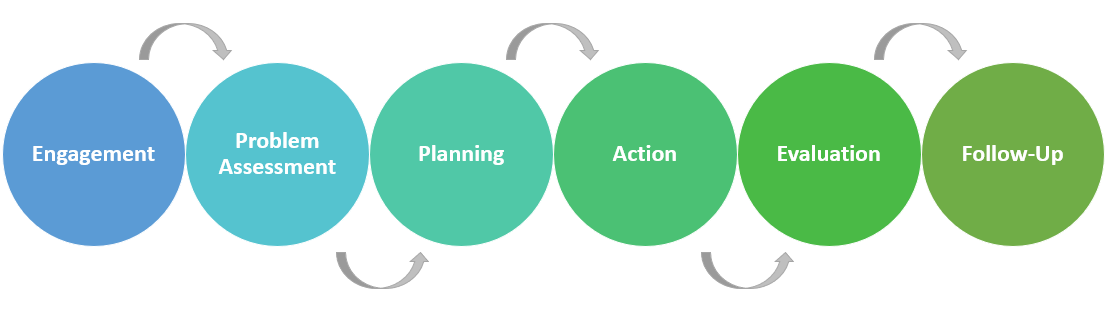

Problem-Solving and Planned Change Model

Helen Harris Perlman started her social work career after facing discrimination as a Jew who was unable to find a professorship in the humanities in the early 20th century. Once she became a caseworker and saw the problems that people face she found that she liked to help people, but felt that the main approach of long term psychotherapy was not effective in all cases. Instead she developed a problem solving approach that focused on one particular aspect of the client’s life and on how to change it. The planned change process was introduced to the social work profession in 1957. To learn more about Helen Harris Perlman and her career at the University of Chicago, read here.

The Planned Change Model consists of a multi-step process which includes:

- Engagement

- Assessment

- Planning

- Implementation

- Evaluation

- Termination

- Follow-up

The Engagement phase is the first interaction between the professional and their client. The engagement stage does not have a predetermined time frame; it can last for a couple of minutes to a few hours depending on the client and the circumstances. It is very important during the engagement phase that the social worker displays active listening skills, eye contact, empathy and empathetic responses, can reflect to the client what has been said, and uses questioning skills (motivational interviewing). It is appropriate to take notes during the engagement phase for assessment purposes or for reflection. Remember, during the engagement phase, the social worker is building a level of rapport and trust with the client.

The Assessment phase is the process occurring between social worker and client in which information is gathered, analyzed and synthesized to provide a concise picture of the client and their needs and strengths. The assessment phase is very important as it is the foundation of the planning and action phases that follow.

During the assessment stages, there are five key points:

- identifying the need or problem

- identify the nature of the problem

- identify strengths and resources

- collect information

- analyze the collected information (Johnson & Yanca, 2010)

The Planning phase is when the client and social worker develop a plan with goals and objectives as to what needs to be done to address the problem. A plan is developed to help the client meet their need or address the problem (Johnson, & Yanca, 2010). The planning phase is a joint process where the worker and the client identify the strengths and resources gathered from the assessment phase. Once the strengths and resources are identified, the social worker and the client come up with a plan by outlining goals, objectives, and tasks to help meets the clients goal to address the need or problem. During the planning phase, keep in mind that the goals should be what the client is comfortable with and finds feasible to obtain. The social worker’s most important job during this phase is to help the client identify strengths and resources, not to come up with the client’s goals for them.

The Implementation/Action phase is when the client and social worker execute a plan to address the areas of concern by completing the objectives to meet the client’s goals. The action phase is also considered a joint phase as the social worker and the client act! The worker and the client begin to work on the task that were identified in the planning phase (Johnson & Yanca, 2010). The worker and the client are responsible for taking on different parts of the identified task; for example, the social worker may find a local food pantry or help with food assistance program if the client needs food. The client may work on making a grocery list of foods that will make bigger portions for leftovers to make food last longer for the family. However, the worker and the client are jointly working together to obtain the goal of providing food for the client and their family.

The Evaluation Phase/Termination phase is a constant. The worker should always evaluate how the client is doing throughout the process of the working relationship (Johnson & Yanca, 2010). When the plan has been completed or the goals have been met, the client and social worker review the goals and objective and evaluate the change and/or the success. If change or progress has not been made the client and social worker will review the goals and objectives and make changes or modifications to meet the goal. Once the goals have been met, termination of services follows if there are no further need for services or other concerns to address. Sometimes termination happens before goal completion, due to hospitalizations, relocation, losing contact with a client, financial hardships , or the inability to engage the client.

The Follow Up phase is when the social worker reaches out to the client to make sure they are still following their goals, using their skills, and making sure the client is doing well. The follow up may not always be possible due to different situations such as death, relocation, or change in contact information.

The diagram below shows the process of the Planned Change Model when working with clients.

Evidence-based Practice (EBP) and Social Problems

Evidence-based practice is the conscientious, explicit and judicious use of current best evidence in making decisions about the care of a client. When working with clients it is important to combine research and clinical expertise. In the fields of human development and family sciences, sociology, and psychology there is constant research being conducted to assess various assessment and treatment modalities. The research that is conducted provides the evidence that professionals use to help our clients improve their living situations and concerns. When new social problems emerge, there is a need to combine existing research and knowledge with best practices, and data that is collected by the government and large agencies in present time. For example, the COVID-19 pandemic presents new challenges and has uncovered existing inequities in our labor and health care systems. Helping professionals must be prepared to help individuals, families, and communities with emerging problems that affect their lives.

People are the experts on their own lives. To be truly client-centered professionals must keep in mind what a person’s values are, and what their preferences are for the outcome of their life situation. It can be tempting to think that as a professional one knows what is best but each individual must be respected.

When working with clients and evidence based practices it is important to know that research is constant surrounding evidence based practices, and as a practicing social worker it is very important to stay abreast of the constant change of new information and changes. It is important to be educated, to collaborate with others, and to respect your clients’ personal values and preferences.

References

Bonecutter, & Gleeson. (n.d.). Genograms and ecomaps: Tools for developing a broad view of family. Retrieved from http://www.tnchildren.org/wp-content/uploads/2014/11/Genograms-and-Ecomaps.pdf

Dziegielewski, S. (2013). The changing face of health care social work (3rd ed.). New York: Springer.

Elements Behavioral Health. (2012, August 10). What are evidence-based practices? Retrieved from https://www.elementsbehavioralhealth.com/addiction-recovery/evidence-based-practices/

Flamand, L. (2017). Systems theory of social work. People of everyday life. Retrieved from http://peopleof.oureverydaylife.com/systems-theory-social-work-6260.html

Inderbitzen, S. (2014, February 3). What does it mean to be a social work generalist? Social work degree guide. Retrieved from http://www.socialworkdegreeguide.com/what-does-it-mean-to-be-a-social-work-generalist/

Johnson, L. C., & Yanca, S. J. (2010). Social work practice: A generalist approach (10th ed.). Boston, MA: Allyn & Bacon.

Kirst-Ashman, K. K., & Hull, G. H., Jr. (2015). Generalist practice with organizations and communities (6th ed.). Pacific Grove, CA: Brooks/Cole.

Lewin, R. G. (2009). Helen Harris Perlman. In Jewish women: A comprehensive historical encyclopedia. Retrieved from https://jwa.org/encyclopedia/article/perlman-helen-harris

Mathainit, M. A., & Meyer, C. H. (2006). Ecosystems perspective: Implications for practice. Retrieved from http://home.earthlink.net/~mattaini/Ecosystems.html

Oswalt, A. (2015). Urie Bronfenbrenner and child development. Gulf Bend Center. Retrieved from http://gulfbend.org/poc/view_doc.php?type=doc&id=7930&cn=28

Pardeck, J. T. (1988). An ecological approach for social work practice. The Journal of Sociology & Social Welfare, 15(2), 134-144. Retrieved from http://scholarworks.wmich.edu/jssw/vol15/iss2/11

Steyaert, J. (2013, April). Ann Hartman. In History of social work. Retrieved from www.historyofsocialwork.org

Licenses and Attributions

Open Content, Shared Previously

Generalist Practice by Aikia Fricke and Ferris State University Department of Social Work, Introduction to Social Work at Ferris State University is licensed under CC BY 4.0.

Figure one. Photo of Aikia Fricke is licensed under CC BY 4.0.

Figure five. Image by fernando zhiminaicela is under the Pixabay License.

Open Content, Original

Figure two. Micro, Mezzo, Macro Visualization by Elizabeth B. Pearce is licensed under CC BY 4.0.

Figure three. Bronfenbrenner’s Ecological Systems Visualization by Elizabeth B. Pearce/ Michaela Willi Hooper is licensed under CC BY 4.0.

Figure four. Planned Change Model Visualization by Elizabeth B. Pearce/ Michaela Willi Hooper is licensed under CC BY 4.0.

All Rights Reserved Content, Shared Previously

Ecomap Animation by Denise Luscombe/Bridget Pieterse (Disability Services Commission and Child and Adolescent Health Service) is under a Standard Youtube License.