2 Ch. 2: Communication Principles and Process

Foundations

Ch. 2: Communication Principles and Process

Learning Objectives

By the end of this chapter, readers should:

- Understand how communication meets various needs.

- Be able to define communication.

- Have a foundational understanding of the communication process.

- Be able to explain how various contexts impact communication.

Key Vocabulary

-

physical needs

-

relational needs

-

communication ethics

-

instrumental needs

-

identity needs

-

self-concept

-

participants

-

message

-

encoding

-

decoding

-

channel

-

linear communication

-

interactional communication

-

transactional communication

-

social context

-

relational context

-

cultural context

Taking this course will likely change how you view communication. Most of us admit that communication is important, but it’s often in the back of our minds or viewed as something that “just happens.” Putting communication at the front of your mind and becoming more aware of how you communicate can be informative and have many positive effects. When I first started studying communication as an undergraduate, I began seeing the concepts we learned in class in my everyday life. When I worked in groups, I was able to apply what I had learned about group communication to improve my performance and overall experience. I also noticed interpersonal concepts and theories as I communicated within various relationships. Whether I was analyzing mediated messages or considering the ethical implications of a decision before I made it, studying communication allowed me to see more of what was going on around me, which allowed me to more actively and competently participate in various communication contexts. In this section, as we learn the principles of communication, I encourage you to take note of aspects of communication that you haven’t thought about before and begin to apply the principles of communication to various parts of your life.

Communication Meets Needs

As a student with years of education experience, you know that communication is far more than the transmission of information. The exchange of messages and information is important for many reasons, but it is not enough to meet the various needs we have as human beings. While the content of our communication may help us achieve certain physical and instrumental needs, it also feeds into our identities and relationships in ways that far exceed the content of what we say.

- Physical needs include needs that keep our bodies and minds functioning like air, food, water, and sleep. Communication, which we most often associate with our brain, mouth, eyes, and ears, actually has many more connections to and effects on our physical body and well-being. At the most basic level, communication can alert others that our physical needs are not being met. Even babies cry when they are hungry or sick to alert their caregiver of the need to satisfy physical needs. Current research indicates that social connection has a huge impact on longevity, our immune systems, and other aspects of physical health (Seppala, et al., 2014).

- Instrumental needs Include needs that help us get things done in our day-to-day lives and achieve short- and long-term goals. We all have short- and long-term goals that we work on every day. Fulfilling these goals is an ongoing communicative task, which means we spend much of our time communicating for instrumental needs. Some common instrumental needs include influencing others, getting information we need, or securing support (Burleson, Metts, & Kirch, 2000). An example could be when Jeon tries to persuade his roommate to turn down his music because he is studying. In this instance, Jeon is using communication to meet an instrumental need.

- Relational needs include needs that help us maintain social bonds and interpersonal relationships. Communicating to fill our instrumental needs helps us function on many levels, but communicating for relational needs helps us achieve the social relating that is an essential part of being human. Communication meets our relational needs by giving us a tool through which to develop, maintain, and end relationships.

- Identity needs include our need to present ourselves to others and be thought of in particular and desired ways. What adjectives would you use to describe yourself? Are you funny, smart, loyal, or quirky? Your answer isn’t just based on who you think you are, since much of how we think of ourselves is based on our communication with other people. Our identity changes as we progress through life, but communication is the primary means of establishing our identity and fulfilling our identity needs.

Communication Is a Process

Communication can be defined as the process of understanding and sharing meaning (Pearson & Nelson, 2000. When we refer to communication as a process, we imply that it doesn’t have a distinct beginning and end or follow a predetermined sequence of events. It can be difficult to trace the origin of a communication encounter, since communication doesn’t always follow a neat and discernible format, which makes studying communication interactions or phenomena difficult. Any time we pull one part of the process out for study or closer examination, we artificially “freeze” the process in order to examine it, which is not something that is possible when communicating in real life. But sometimes scholars want to isolate a particular stage in the process in order to gain insight by studying, for example, feedback or eye contact. Doing that changes the very process itself, and by the time you have examined a particular stage or component of the process, the entire process may have changed. However, these behavioral snapshots are useful for scholarly interrogation of the communication process, and they can also help us evaluate our own communication practices, troubleshoot a problematic encounter we had, or slow things down to account for various contexts before we engage in communication (Dance & Larson, 1976).

Communication Is Guided by Culture and Context

Context is a dynamic component of the communication process. Culture and context also influence how we perceive and define communication. Western culture tends to put more value on senders than receivers and on the content rather the context of a message whereas Eastern cultures tend to communicate with the listener in mind. These cultural values are reflected in our definitions and models of communication. As we will learn in later chapters, cultures vary in terms of having a more individualistic or more collectivistic cultural orientation. The United States is considered an individualistic culture, where emphasis is put on individual expression and success. Japan is considered a collectivistic culture, where emphasis is put on group cohesion and harmony. These are strong cultural values that are embedded in how we learn to communicate. In many collectivistic cultures, there is more emphasis placed on silence and nonverbal context. Whether in the United States, Japan, or another country, people are socialized from birth to communicate in culturally specific ways that vary by context.

Communication Is Learned

Most of us are born with the capacity and ability to communicate, but we all communicate differently. This is because communication is learned rather than innate. As we have already seen, communication patterns are relative to the context and culture in which one is communicating. Many cultures have distinct languages consisting of unique systems of symbols. A key principle of communication is that it is symbolic. Communication is symbolic in that the words that make up our language systems do not directly correspond to something in reality. Instead, they stand in for or symbolize something. Odgen and Richards (1923) believe that there is a triangle of meaning with “thought,” “symbol,” and “referent” in relationship.

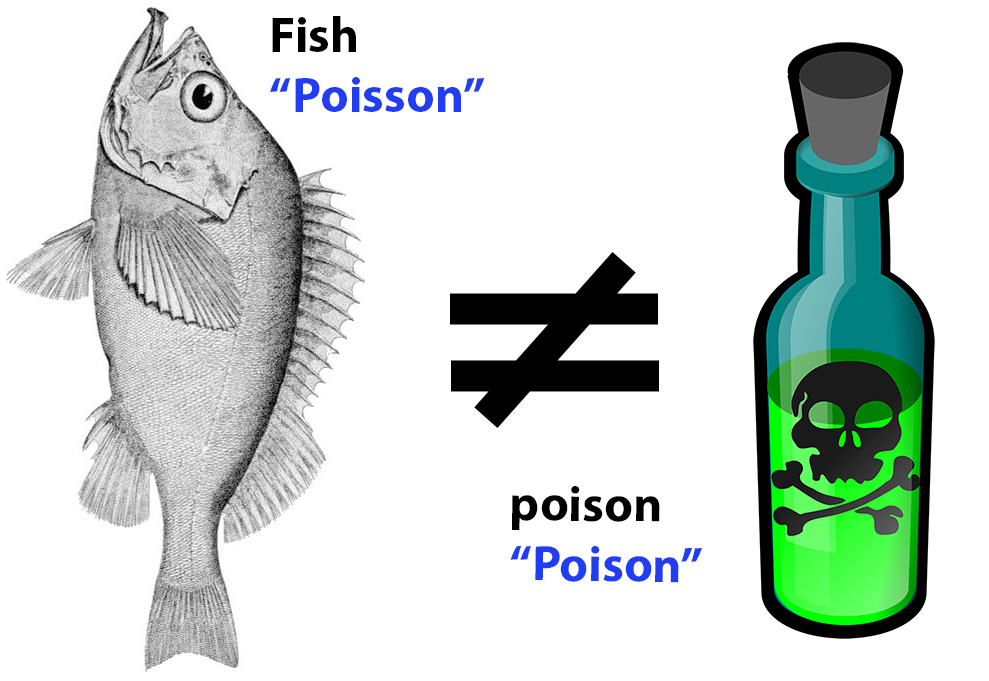

The fact that communication varies so much among people, contexts, and cultures illustrates the principle that meaning is not inherent in the words we use. For example, let’s say you go to France on vacation and see the word poisson on the menu. Unless you know how to read French, you will not know that the symbol is the same as the English symbol fish. Those two words don’t look the same at all, yet they symbolize the same object. If you went by how the word looks alone, you might think that the French word for fish is more like the English word poison and avoid choosing that for your dinner. Putting a picture of a fish on a menu would definitely help a foreign tourist understand what they are ordering, since the picture is an actual representation of the object rather than an arbitrary symbol for it.

All symbolic communication is learned, negotiated, and dynamic. We know that the letters b-o-o-k refer to a bound object with multiple written pages. We also know that the letters t-r-u-c-k refer to a vehicle with a bed in the back for hauling things. But if we learned in school that the letters t-r-u-c-k referred to a bound object with written pages and b-o-o-k referred to a vehicle with a bed in the back, then that would make just as much sense, because the letters don’t actually refer to the object and the word itself only has the meaning that we assign to it. We will learn more, in the verbal communication chapter, about how language works, but communication is more than the words we use.

We are all socialized into different languages, but we also speak different “languages” based on the situation we are in. For example, in some cultures it is considered inappropriate to talk about family or health issues in public, but it wouldn’t be odd to overhear people in a small town grocery store in the United States talking about their children or their upcoming surgery. There are some communication patterns shared by very large numbers of people and some that are particular to a specific relationship–best friends, for example, who have their own inside terminology and expressions that wouldn’t make sense to anyone else. These examples aren’t on the same scale as differing languages, but they still indicate that communication is learned. They also illustrate how rules and norms influence how we communicate. We will discuss rules and norms in communication in later chapters.

Communication Has Ethical Implications

Another culturally and situationally relative principle of communication is the fact that communication has ethical implications. Communication ethics deal with the process of negotiating and reflecting on our actions and communication regarding what we believe to be right and wrong. Aristotle, an important Greek philosopher and influencer of communication studies said, “In the arena of human life the honors and rewards fall to those who show their good qualities in action” (Pearson et al., 2006).

In communication ethics, we are more concerned with the decisions people make about what is right and wrong than the systems, philosophies, or religions that inform those decisions. Much of ethics is gray area. Although we talk about making decisions in terms of what is right and what is wrong, the choice is rarely that simple. Aristotle goes on to say that we should act “to the right extent, at the right time, with the right motive, and in the right way.”

Communication has broad ethical implications. When dealing with communication ethics, it’s difficult to state that something is 100 percent ethical or unethical. I tell my students that we all make choices daily that are more ethical or less ethical, and we may confidently make a decision only later to learn that it wasn’t the most ethical option. In such cases, our ethics and goodwill are tested, since in any given situation multiple options may seem appropriate, but we can only choose one. If, in a situation, we make a decision and we reflect on it and realize we could have made a more ethical choice, does that make us a bad person?

While many behaviors can be more easily labeled as ethical or unethical, communication isn’t always as clear. Murdering someone is generally thought of as unethical and illegal, but many instances of hurtful speech, or even what some would consider hate speech, have been protected as free speech. This shows the complicated relationship between protected speech, ethical speech, and the law. In some cases, people see it as their ethical duty to communicate information that they feel is in the public’s best interest. The people behind WikiLeaks, for example, have released thousands of classified documents related to wars, intelligence gathering, and diplomatic communication. WikiLeaks claims that exposing this information keeps politicians and leaders accountable and keeps the public informed, but government officials claim the release of the information should be considered a criminal act because such exposure may threaten national security. Both parties consider the other’s communication unethical and their own communication ethical. Who is right?

Communication Influences Your Thinking about Yourself and Others

We all share a fundamental drive to communicate. As previously stated, communication can be defined as the process of understanding and sharing meaning (Pearson & Nelson, 2000). . You share meaning in what you say and how you say it, both in oral and written forms. If you could not communicate, what would life be like? A series of never-ending frustrations? Not being able to ask for what you need, or even to understand the needs of others?

Being unable to communicate might even mean losing a part of yourself, for you communicate your self-concept—your sense of self and awareness of who you are—in many ways. Do you like to write? Do you find it easy to make a phone call to a stranger, or to speak to a room full of people? Do you like to work in teams and groups? Perhaps someone told you that you don’t speak clearly, or your grammar needs improvement. Does that make you more or less likely to want to communicate? For some it may be a positive challenge, while for others it may be discouraging, but in all cases your ability to communicate is central to your self-concept.

Take a look at your clothes. What are the brands you are wearing? What do you think they say about you? Do you feel that certain styles of shoes, jewelry, tattoos, music, or even automobiles express who you are? Part of your self-concept may be that you express yourself through texting, or through writing longer documents like essays and research papers, or through the way you speak. Those labels and brands that you wear also in some ways communicate with your group or community. They are recognized, and to some degree, are associated with you. Just as your words represent you in writing, how you present yourself with symbols and images influences how others perceive you.

On the other side of the coin, your communication skills help you to understand others—not just their words, but also their tone of voice, their nonverbal gestures, or the format of their written documents provide you with clues about who they are and what their values and priorities may be. Your success as a communicator hinges on your ability to actively listen and accurately interpret others’ messages.

Communication Influences How You Learn

When you were an infant, you learned to talk over a period of many months. There was a group of caregivers around you that talked to each other, and sometimes you, and you caught on that you could get something when you used a word correctly. Before you knew it you were speaking in sentences, with words, in a language you learned from your family or those around you. When you got older, you didn’t learn to ride a bike, drive a car, or even text a message on your cell phone in one brief moment. Learning works the same way with the continuous improvement of your communication skills.

You learn to speak in public by first having conversations, then by answering questions and expressing your opinions in class, and finally by preparing and delivering a “stand-up” speech. Similarly, you learn to write by first learning to read, then by writing and learning to think critically. Your speaking and writing are reflections of your thoughts, experience, and education, and part of that combination is your level of experience listening to other speakers, reading documents and styles of writing, and studying formats similar to what you aim to produce. Speaking and writing are both key communication skills that you will use in teams and groups.

As you study communication, you may receive suggestions for improvement and clarification from professionals more experienced than yourself. Take their suggestions as challenges to improve, don’t give up when your first speech or first draft does not communicate the message you intend. Stick with it until you get it right. Your success in communicating is a skill that applies to almost every field of work, and it makes a difference in your relationships with others.

Remember, luck is simply a combination of preparation and timing. You want to be prepared to communicate well when given the opportunity. Each time you do a good job, your success will bring more success.

The Communication Process

Communication is a complex process, and it is difficult to determine where or with whom a communication encounter starts and ends. For example, when you finish your best friends’ sentences before they can even get the words out, who is the sender, and who is the receiver? Models of communication simplify the process by providing a visual representation of the various aspects of a communication encounter. Models allow us to see specific concepts and steps within the process of communication, define communication, and apply communication concepts. When you become aware of how communication functions, you can think more deliberately through your communication encounters, which can help you better prepare for future communication and learn from your previous communication. The three models of communication we will discuss are the transmission, interaction, and transaction models.

Although the models differ, they all contain some common elements such as participants, messages, encoding, decoding, and channels. In communication models, the participants are the senders and/or receivers of messages in a communication encounter. The message is the verbal or nonverbal content being conveyed from sender to receiver. For example, when you say “Hello!” to your friend, you are sending a message of greeting that will be received by your friend.

The internal cognitive processes that allow participants to send, receive, and understand messages are the encoding process and decoding process. Encoding is the process of turning thoughts into communication. As we will learn later, the level of conscious thought that goes into encoding messages varies. Decoding is the process of turning communication into thoughts. For example, you may realize you’re hungry and encode the following message to send to your roommate: “I’m hungry. Do you want to get pizza tonight?” As your roommate receives the message, he decodes what you are expressing to him and turns it back into thoughts in order to make meaning out of it. Of course, we don’t just communicate verbally—we have various options, or channels for communication. Encoded messages are sent through a channel, or a sensory route on which a message travels, to the receiver for decoding. While communication can be sent and received using any sensory route (sight, smell, touch, taste, or sound), most communication occurs through visual (sight) and/or auditory (sound) channels. If your roommate has headphones on and is engrossed in a video game, you may need to get his attention by waving your hands before you can ask him about dinner.

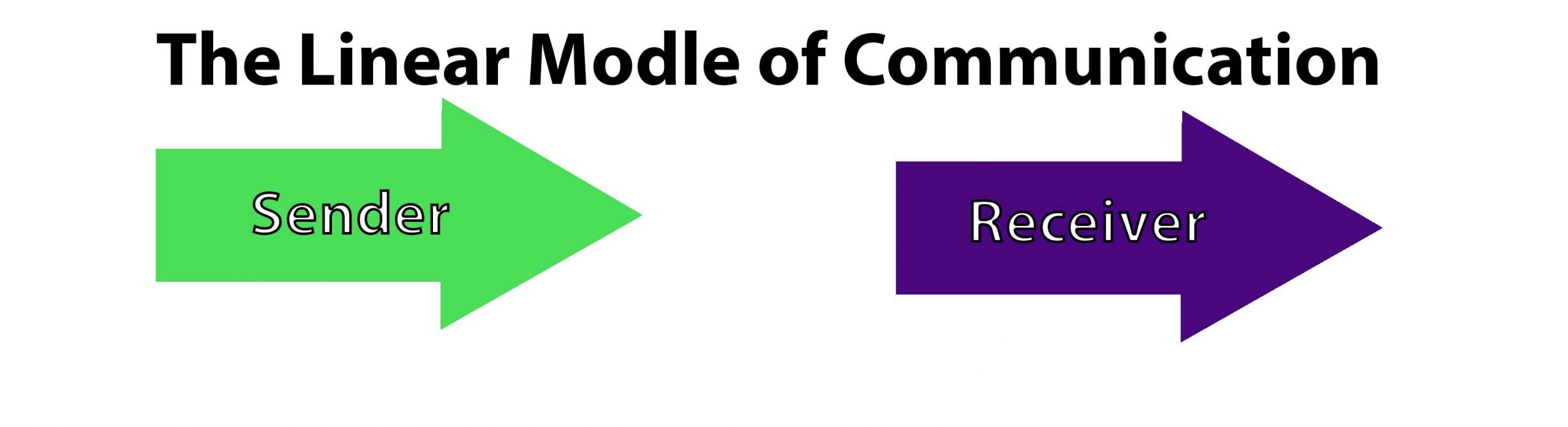

Linear Model of Communication

The linear model of communication describes communication as a linear, one-way process in which a sender intentionally transmits a message to a receiver (Ellis & McClintock, 1990). This model focuses on the sender and message within a communication encounter. Although the receiver is included in the model, this role is viewed as more of a target or end point rather than part of an ongoing process. We are left to presume that the receiver either successfully receives and understands the message or does not. The scholars who designed this model extended on a linear model proposed by Aristotle centuries before that included a speaker, message, and hearer. They were also influenced by the advent and spread of new communication technologies of the time such as telegraphy and radio, and you can probably see these technical influences within the model (Shannon & Weaver, 1949). Think of how a radio message is sent from a person in the radio studio to you listening in your car. The sender is the radio announcer who encodes a verbal message that is transmitted by a radio tower through electromagnetic waves (the channel) and eventually reaches your (the receiver’s) ears via an antenna and speakers in order to be decoded. The radio announcer doesn’t really know if you receive his or her message or not, but if the equipment is working and the channel is free of static, then there is a good chance that the message was successfully received.

Although the linear model may seem simple or even underdeveloped to us today, the creation of this model allowed scholars to examine the communication process in new ways, which eventually led to more complex models and theories of communication that we will discuss more later. This model is not quite rich enough to capture dynamic face-to-face interactions, but there are instances in which communication is one-way and linear, especially computer-mediated communication (CMC). CMC is integrated into many aspects of our lives now and has opened up new ways of communicating and brought some new challenges. Think of text messaging for example. The linear model of communication is well suited for describing the act of text messaging since the sender isn’t sure that the meaning was effectively conveyed or that the message was received at all.

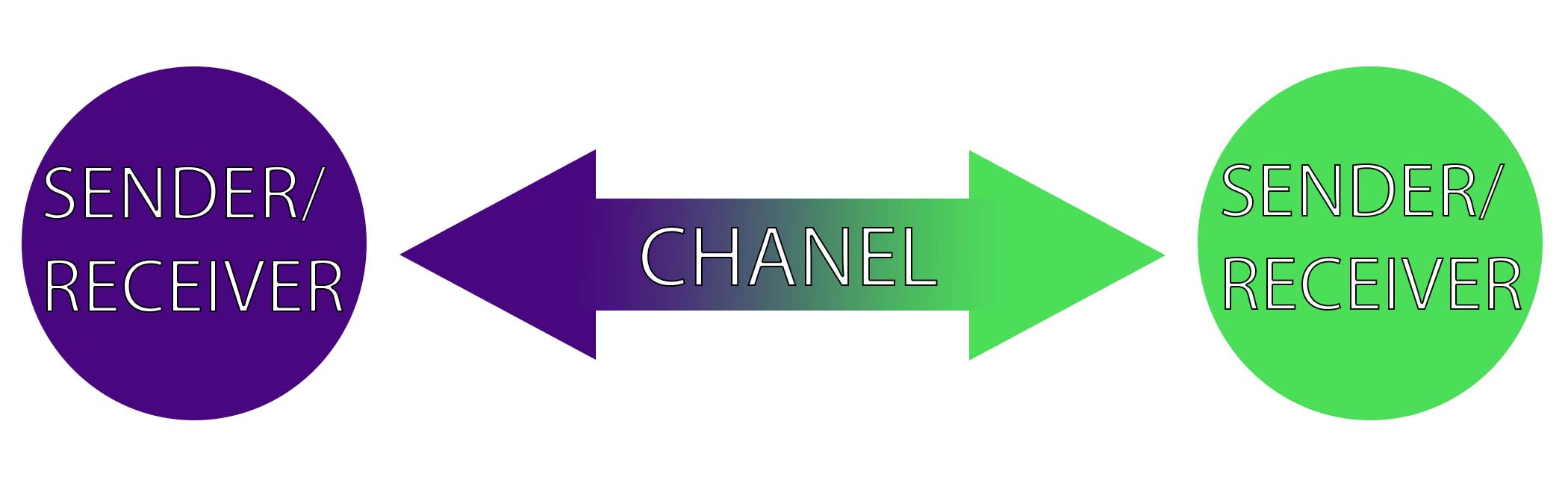

Interactional Model of Communication

The interactional model of communication describes communication as a process in which participants alternate positions as sender and receiver and generate meaning by sending messages and receiving feedback within physical and psychological contexts (Schramm et al., 1997). Rather than illustrating communication as a linear, one- way process, the interaction model incorporates feedback, which makes communication a more interactive, two- way process. Feedback includes messages sent in response to other messages. For example, your instructor may respond to a point you raise during class discussion or you may point to the sofa when your roommate asks you where the remote control is. The inclusion of a feedback loop also leads to a more complex understanding of the roles of participants in a communication encounter. Rather than having one sender, one message, and one receiver, this model has two sender-receivers who exchange messages. Each participant alternates roles as sender and receiver in order to keep a communication encounter going. Although this seems like a perceptible and deliberate process, we alternate between the roles of sender and receiver very quickly and often without conscious thought.

The interactional model is focused on both the message and interaction. While the linear model focused on transmitting a message, the interactional model is more concerned with the communication loop itself. Feedback and context help make the interactional model a more accurate illustration of the typical communication process, and is a powerful tool that helps us understand communication encounters.

Transactional Model of Communication

As the study of communication progressed, models expanded to account for more of the communication process. Many scholars view communication as more than a process that is used to carry on conversations and convey meaning. We don’t send messages like computers, and we don’t neatly alternate between the roles of sender and receiver as an interaction unfolds. We also can’t consciously decide to stop communicating, because communication is more than sending and receiving messages. The transactional model differs from the linear and interactional models in significant ways, including the conceptualization of communication, the role of sender and receiver, and the role of context (Barnlund, 1970).

To review, each model incorporates a different understanding of what communication is and what communication does. The linear model views communication as a thing, like an information packet, that is sent from one place to another. From this view, communication is defined as sending and receiving messages. The interactional model views communication as an interaction in which a message is sent and then followed by a reaction (feedback), which is then followed by another reaction, and so on. From this view, communication is defined as producing conversations and interactions within physical and psychological contexts. The transactional model views communication as integrated into our social realities in such a way that it helps us not only understand them but also create and change them.

The transactional model of communication describes communication as a process in which communicators generate social realities within social, relational, and cultural contexts. In this model, we don’t just communicate to exchange messages; we communicate to create relationships, form intercultural alliances, shape our self-concepts, and engage with others in dialogue to create communities. In short, we don’t communicate about our realities; communication helps to construct our realities.

The roles of sender and receiver in the transactional model of communication differ significantly from the other models. Instead of labeling participants as senders and receivers, the people in a communication encounter are referred to as communicators. Unlike the interactional model, which suggests that participants alternate positions as sender and receiver, the transactional model suggests that we are simultaneously senders and receivers. For example, on a first date, as you send verbal messages about your interests and background, your date reacts nonverbally. You don’t wait until you are done sending your verbal message to start receiving and decoding the nonverbal messages of your date. Instead, you are simultaneously sending your verbal message and receiving your date’s nonverbal messages. This is an important addition to the model because it allows us to understand how we are able to adapt our communication—for example, a verbal message—in the middle of sending it based on the communication we are simultaneously receiving from our communication partner.

The transactional model also includes a more complex understanding of context. The interaction model portrays context as physical and psychological influences that enhance or impede communication. While these contexts are important, they focus on message transmission and reception. Since the transaction model of communication views communication as a force that shapes our realities before and after specific interactions occur, it must account for contextual influences outside of a single interaction. To do this, the transactional model considers how social, relational, cultural, and physical contexts frame and influence our communication encounters.

- Social context refers to the stated rules or unstated norms that guide communication. As we are socialized into our various communities, we learn rules and implicitly pick up on norms for communicating. Some common rules that influence social contexts include don’t lie to people, don’t interrupt people, don’t pass people in line, greet people when they greet you, thank people when they pay you a compliment, and so on. Parents and teachers often explicitly convey these rules to their children or students. Rules may be stated over and over, and there may be punishment for not following them. Norms are social conventions that we pick up on through observation, practice, and trial and error. We may not even know we are breaking a social norm until we notice people looking at us strangely or someone corrects or teases us. For example, as a new employee you may over- or underdress for the company’s holiday party because you don’t know the norm for formality. Although there probably isn’t a stated rule about how to dress at the holiday party, you will notice your error without someone having to point it out, and you will likely not deviate from the norm again in order to save yourself any potential embarrassment. Even though breaking social norms doesn’t result in the formal punishment that might be a consequence of breaking a social rule, the social awkwardness we feel when we violate social norms is usually enough to teach us that these norms are powerful even though they aren’t made explicit like rules. Norms even have the power to override social rules in some situations. To go back to the examples of common social rules mentioned before, we may break the rule about not lying if the lie is meant to save someone from feeling hurt. We often interrupt close friends when we’re having an exciting conversation, but we wouldn’t be as likely to interrupt a professor while they are lecturing. Since norms and rules vary among people and cultures, relational and cultural contexts are also included in the transaction model in order to help us understand the multiple contexts that influence our communication.

- Relational context includes the previous interpersonal history and type of relationship we have with a person. We communicate differently with someone we just met versus someone we’ve known for a long time. Initial interactions with people tend to be more highly scripted and governed by established norms and rules, but when we have an established relational context, we may be able to bend or break social norms and rules more easily. For example, you would likely follow social norms of politeness and attentiveness and might spend the whole day cleaning the house for the first time you invite your new neighbors to visit. Once the neighbors are in your house, you may also make them the center of your attention during their visit. If you end up becoming friends with your neighbors and establishing a relational context, you might not think as much about having everything cleaned and prepared or even giving them your whole attention during later visits. Since communication norms and rules also vary based on the type of relationship people have, relationship type is also included in relational context. For example, there are certain communication rules and norms that apply to a supervisor-supervisee relationship that don’t apply to a brother-sister relationship and vice versa. Just as social norms and relational history influence how we communicate, so does culture.

- Cultural context includes various aspects of identities such as race, gender, nationality, ethnicity, sexual orientation, class, and ability. We will learn more about these identities in other chapters, but for now it is important for us to understand that whether we are aware of it or not, we all have multiple cultural identities that influence our communication. Some people, especially those with identities that have been historically marginalized, are regularly aware of how their cultural identities influence their communication and influence how others communicate with them. Conversely, people with identities that are dominant or in the majority may rarely, if ever, think about the role their cultural identities play in their communication. When cultural context comes to the forefront of a communication encounter, it can be difficult to manage. Since intercultural communication creates uncertainty, it can deter people from communicating across cultures or lead people to view intercultural communication as negative. But if you avoid communicating across cultural identities, you will likely not get more comfortable or competent as a communicator. “Difference,” isn’t a bad thing. In fact, intercultural communication has the potential to enrich various aspects of our lives. In order to communicate well within various cultural contexts, it is important to keep an open mind and avoid making assumptions about others’ cultural identities. While you may be able to identify some aspects of the cultural context within a communication encounter, there may also be cultural influences that you can’t see. A competent communicator shouldn’t assume to know all the cultural contexts a person brings to an encounter, since not all cultural identities are visible. As with the other contexts, it requires skill to adapt to shifting contexts, and the best way to develop these skills is through practice and reflection.

References:

This chapter contains material taken from Chapter 1 “The communication process”in Communication in the real world: An introduction to communication studies and is used under a CC-BY-NC-SA 4.0 International license.