3 Ch. 3: Cultural Characteristics and the Roots of Culture

Foundations

Ch. 3: Cultural Characteristics and the Roots of Culture

Learning Objectives

By the end of this chapter, readers should:

- Explain what culture is and define it in several ways.

- Discuss the effect that culture has on communication.

- Describe the role of power in culture and communication.

- Discuss Kluckhohn and Strodtbeck’s Value Orientation Theory.

- Discuss Hofestede’s Dimensions of National Culture Theory.

- Discuss Edward T. Hall’s Theories.

Key Vocabulary

-

collectivism

-

ethnocentrism

-

heterogeneous

-

individualism

-

uncertainty avoidance

-

uncertainty reduction theory

-

space

-

power distance

-

high vs. low context

-

femininity vs. masculinity

-

short-term orientation vs.

long-term orientation -

polychronic vs.

monochronic Cultures -

proxemics

-

values

-

worldviews

-

assumption

-

co-culture

What does the term “culture” mean to you? Is it the apex of knowledge and intellectual achievement? A particular nation, people or social group? Rituals, symbols and myths? The arbiter of what is right and wrong behavior?

It has become quite common to describe natural groupings that humans create as a “culture.” Popular media has given us women’s culture, men’s culture, workplace cultures, specially-abled culture, pet culture, school culture, exercise culture, and the list goes on. But, are all these divisions really classified as culture? For the purposes of this textbook, the answer is no. Cultural communication researcher, Donal Carbaugh (1988) defines culture as “a system of symbols, premises, rules, forms, and the domains and dimensions of mutual meanings associated with these.”

Carbaugh was expanding on the work of anthropologist Clifford Geertz, who believed that culture was a system based on symbols. Geertz said that people use symbols to define their world and express their emotions. As human beings, we all learn about the world around us, both consciously and unconsciously, starting at a very young age. What we internalize comes through observation, experience, interaction, and what we are taught. We manipulate symbols to create meaning and stories that dictate our behaviors, to organize our lives, and to interact with others. The meanings we attach to symbols are arbitrary. Looking someone in the eye means that you are direct and respectful in some countries, yet, in other cultural systems, looking away is a sign of respect.

Carbaugh also suggested that culture is “a learned set of shared interpretations and beliefs, values, and norms, which affect the behaviors of a relatively large group of people.” Our course will combine Carbaugh’s longer definitions into the statement that culture is a learned pattern of values, beliefs, and behaviors shared by a large group of people. It is within this framework that we will explore what happens when people from different cultural backgrounds interact.

Culture is Learned

Although there is a debate as to whether babies are born into the world as tabula rasa (blank slate) or without knowing anything. We can say that they do not come with pre-programmed preferences like your personal computer or cell phone. And, although human beings do share some universal habits such as eating and sleeping, these habits are biologically and physiologically based, not culturally based. Culture is the unique way that we have learned to eat and sleep. Other members of our culture have taught us slowly and consciously (or even subconsciously) what it means to eat and sleep.

Values and Culture

Value systems are fundamental to understanding how culture expresses itself. Values are deeply felt and often serve as principles that guide people in their perceptions and behaviors. Using our values, certain ideas are judged to be right or wrong, good or bad, important or not important, desirable or not desirable. Common values include fairness, respect, integrity, compassion, happiness, kindness, creativity, curiosity, religion, wisdom, and more.

Ideally, our values should match up with what we say we will do, but sometimes our various values come into conflict, and a choice has to be made as to which one will be given preference over another. An example of this could be love of country and love of family. You might love both, but ultimate choose family over country when a crisis occurs.

Beliefs and Culture

Our values are supported by our assumptions of our world. Assumptions are ideas that we believe and hold to be true. Beliefs come about through repetition. This repetition becomes a habit we form and leads to habitual patterns of thinking and doing. We do not realize our assumptions because they are in-grained in us at an unconscious level. We become aware of our assumptions when we encounter a value or belief that is different from our own, and it makes us feel that we need to stand up for, or validate, our beliefs.

People from the United States strongly believe in independence. They consider themselves as separate individuals in control of their own lives. The Declaration of Independence states that all people—not groups, but individual people—are created equal. This sense of equality leads to the idea that all people are of the same standing or importance, and therefore, informality or lack of rigid social protocol is common. This leads to an informality of speech, dress, and manners that other cultures might find difficult to negotiate because of their own beliefs, assumptions, and behaviors.

Beliefs are part of every human life in all world cultures. They define for us, and give meaning to, objects, people, places, and things in our lives. Our assumptions about our world determine how we react emotionally and what actions we need to take. These assumptions about our worldviews guide our behaviors and shape our attitudes. Mary Clark (2005) defines worldviews as “beliefs and assumptions by which an individual makes sense of experiences that are hidden deep within the language and traditions of the surrounding society.” Worldviews are the shared values and beliefs that form the customs, behaviors and foundations of any particular society. Worldviews “set the ground rules for shared cultural meaning” (Clark, 2005). Worldviews are the patterns developed through interactions within families, neighborhoods, schools, communities, churches, and so on. Worldviews can be resources for understanding and analyzing the fundamental differences between cultures.

Feelings and Culture

Our culture can give us a sense of familiarity and comfort in a variety of contexts. We embody a sense of ethnocentrism. Ethnocentrism is the belief that one’s own culture is superior to all other’s and is the standard by which all other cultures should be measured (Sumner, 1906). An example of this could be the farm-to-table movement that is currently popular in the United States. Different parts of the country, pride themselves in growing produce for local consumption touting the benefits of better food, enhanced economy, and carbon neutrality. Tasting menus are developed, awards are given, and consumers brag about the amazing, innovative benefits of living in the United States. What is often missed is the fact that for many people, in many cultures across the planet, the farm-to-table process has not changed for thousands of years. Being a locavore is the only way they know.

Geertz (1973) believed the meanings we attach to our cultural symbols can create chaos when we meet someone who believes in a different meaning or interpretation; it can give us culture shock. This shock can be disorientating, confusing, or surprising. It can bring on anxiety or nervousness, and, for some, a sense of losing control. Culture is always provoking a variety of feelings. Culture shock will be discussed in greater depth in the next chapter.

Behavior and Culture

Our worldview influences our behaviors. Behaviors endure over time and are passed from person to person. Within a dominant or national culture, members can belong to many different groups. Dominant cultures may be made up of many subsets or co-cultures that exist within them. For example, your dominant or national culture may be the United States, but you are also a thirty-year-old woman from the Midwest who loves poodles. Because you are a thirty-year-old woman, you exist in the world very differently than a fifty-year-old man. A co-culture is a group whose values, beliefs or behaviors set it apart from the larger culture of which it is a part of and shares many similarities. (Orbe, 1996) Social psychologists may prefer the term micro-culture as opposed to co-culture.

Culture is Dynamic and Heterogeneous

In addition to exploring the components of the definition, it should be understood that culture is always changing. Cultural patterns are not rigid but slowly and constantly changing. The United States of the 1960s is not the United States of today. Nor if I know one person from the United States do I know them all. Within cultures there are struggles to negotiate relationships within a multitude of forces of change. Although the general nature of this book focuses on broad principles, by viewing any culture as diverse in character or content (heterogeneous), we are better equipped to understand the complexities of that culture and become more sensitive to how people in that culture live.

Describing Culture

Anyone who has had an intercultural encounter or participated in intercultural communication can tell you that they encountered differences between themselves and others. Acknowledging the differences isn’t difficult. Rather, the difficulties come from describing the differences using terms that accurately convey the subtle meanings within cultures.

The study of cross-cultural analysis incorporates the fields of anthropology, sociology, psychology, and communication. Within cross-cultural analysis, several names dominate our understanding of culture—Florence Kluckhohn, Fred Strodtbeck, Geert Hofstede and Edward T. Hall. Although new ideas are continually being proposed, Hofstede remains the leading thinker on how we see cultures.

This section will review both the thinkers and the main components of how they define culture. These theories provide a comprehensive and enduring understanding of the key factors that shape a culture. By understanding the key concepts and theories, you should be able to formulate your own analysis of the different cultures.

Value Orientation Theory

The Kluckhohn-Strodtbeck Value Orientations theory represents one of the earliest efforts to develop a cross-cultural theory of values. According to Kluckhohn and Strodtbeck (1961), every culture faces the same basic survival needs and must answer the same universal questions. It is out of this need that cultural values arise. The basic questions faced by people everywhere fall into five categories and reflect concerns about: 1) human nature, 2) the relationship between human beings and the natural world, 3) time, 4) human activity, and 5) social relations. Kluckhohn and Strodtbeck hypothesized three possible responses or orientations to each of the concerns.

SUMMARY OF KLUCKHOHN-STRODTBECK VALUES ORIENTATION THEORY

Basic Concerns |

Orientations |

||

Human nature |

Evil |

Mixed |

Good |

Relationship to natural world |

Mastery |

Harmony |

Submission |

Time |

Past |

Present |

Future |

Activity |

Being |

Becoming |

Doing |

Social relations |

Collective |

Collateral |

Individual |

What is the inherent nature of human beings?

According to Kluckhohn and Strodtbeck, this is a question that all societies ask, and there are generally three different responses. The people in some societies are inclined to believe that people are inherently evil and that the society must exercise strong measures to keep the evil impulses of people in check. On the other hand, other societies are more likely to see human beings as basically good and possessing an inherent tendency towards goodness. Between these two poles are societies that see human beings as possessing the potential to be either good or evil depending upon the influences that surround them. Societies also differ on whether human nature is immutable (unchangeable) or mutable (changeable).

What is the relationship between human beings and the natural world?

Some societies believe nature is a powerful force in the face of which human beings are essentially helpless. We could describe this as “nature over humans.” Other societies are more likely to believe that through intelligence and the application of knowledge, humans can control nature. In other words, they embrace a “humans over nature” position. Between these two extremes are the societies who believe humans are wise to strive to live in “harmony with nature.”

What is the best way to think about time?

Some societies are rooted in the past, believing that people should learn from history and strive to preserve the traditions of the past. Other societies place more value on the here and now, believing people should live fully in the present. Then there are societies that place the greatest value on the future, believing people should always delay immediate satisfactions while they plan and work hard to make a better future.

What is the proper mode of human activity?

In some societies, “being” is the most valued orientation. Striving for great things is not necessary or important. In other societies, “becoming” is what is most valued. Life is regarded as a process of continual unfolding. Our purpose on earth, the people might say, is to become fully human. Finally, there are societies that are primarily oriented to “doing.” In such societies, people are likely to think of the inactive life as a wasted life. People are more likely to express the view that we are here to work hard and that human worth is measured by the sum of accomplishments.

What is the ideal relationship between the individual and society?

Expressed another way, we can say the concern is about how a society is best organized. People in some societies think it most natural that a society be organized [by groups or collectives]. They hold to the view that some people should lead and others should follow. Leaders, they feel, should make all the important decisions [for the group]. Other societies are best described as valuing collateral relationships. In such societies, everyone has an important role to play in society; therefore, important decisions should be made by consensus. In still other societies, the individual is the primary unit of society. In societies that place great value on individualism, people are likely to believe that each person should have control over his/her own destiny. When groups convene to make decisions, they should follow the principle of “one person, one vote.”

As Hill (2002) has observed, Kluckhohn and Strodtbeck did not consider the theory to be complete. In fact, they originally proposed a sixth value orientation—Space: here, there, or far away, which they could not quite figure out how to investigate at the time. Today, the Kluckhohn and Strodtbeck framework is just one among many attempts to study universal human values.

Hofstede’s Dimensions of National Culture Theory

Geert Hofstede, sometimes called the father of modern cross-cultural science and thinking, is a social psychologist who focused on a comparison of nations using a statistical analysis of two unique databases. The first and largest database composed of answers that matched employee samples from forty different countries to the same survey questions focused on attitudes and beliefs. The second consisted of answers to some of the same questions by Hofstede’s executive students who came from fifteen countries and from a variety of companies and industries. He developed a framework for understanding the systematic differences between nations in these two databases. This framework focused on value dimensions. Values, in this case, are broad preferences for one state of affairs over others, and they are mostly unconscious.

Most of us understand that values are our own culture’s or society’s ideas about what is good, bad, acceptable, or unacceptable. Hofstede developed a framework for understanding how these values underlie organizational behavior. Through his database research, he identified five key value dimensions (power distance, individualism, masculinity, uncertainty avoidance, & time) that analyze and interpret the behaviors, values, and attitudes of a national culture (Hofstede, 1980).

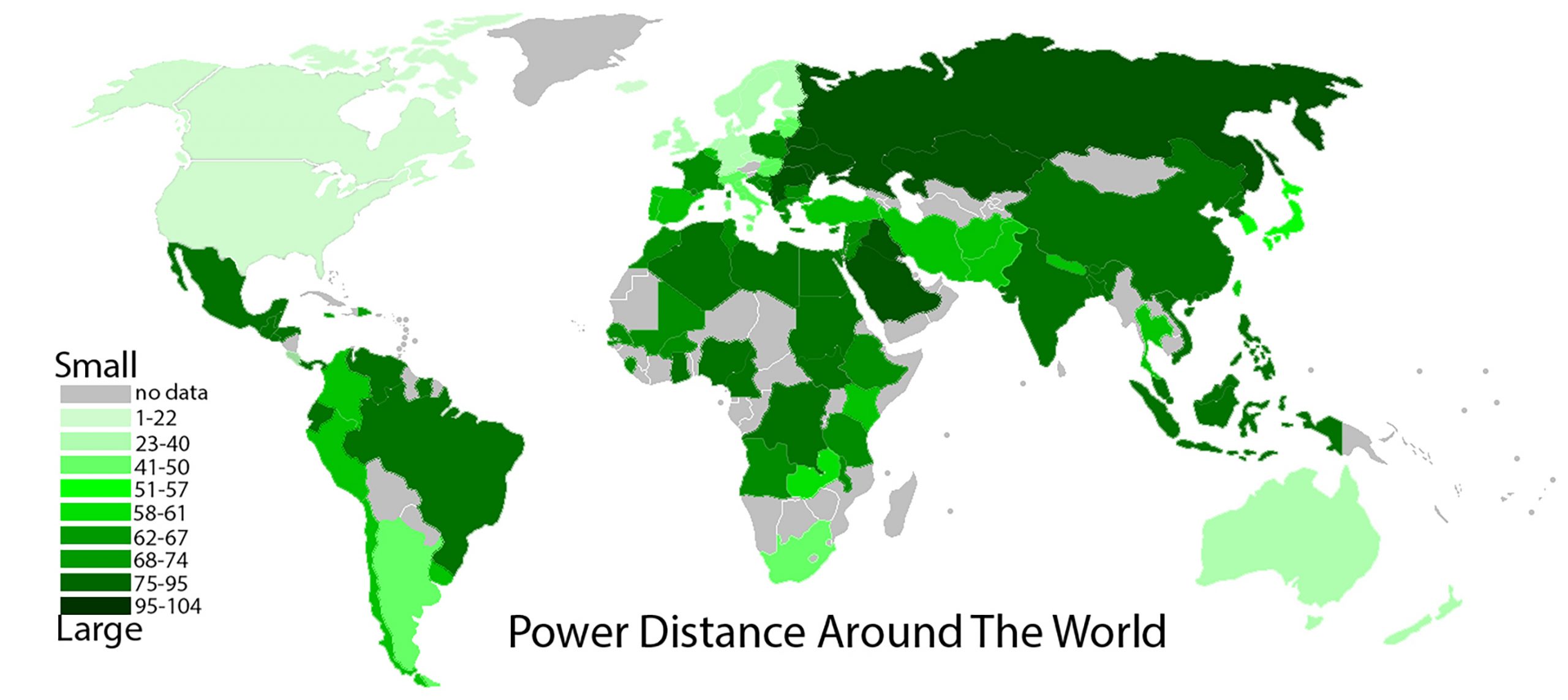

Power Distance

Power distance refers to how openly a society or culture accepts or does not accept differences between people, as in hierarchies in the workplace, in politics, and so on. For example, high power distance cultures openly accept that a boss is “higher” and as such deserves a more formal respect and authority. Examples of these cultures include Japan, Mexico, and the Philippines. In Japan or Mexico, the senior person is almost a father figure and is automatically given respect and usually loyalty without questions.

In Southern Europe, Latin America, and much of Asia, power is an integral part of the social equation. People tend to accept relationships of servitude. An individual’s status, age, and seniority command respect—they’re what make it all right for the lower-ranked person to take orders. Subordinates expect to be told what to do and won’t take initiative or speak their minds unless a manager explicitly asks for their opinion.

At the other end of the spectrum are low power distance cultures, in which superiors and subordinates are more likely to see each other as equal in power. Countries found at this end of the spectrum include Austria and Denmark. To be sure, not all cultures view power in the same ways. In Sweden, Norway, and Israel, for example, respect for equality is a warranty of freedom. Subordinates and managers alike often have carte blanche to speak their minds.

Interestingly enough, research indicates that the United States tilts toward low power distance but is more in the middle of the scale than Germany and the United Kingdom. The United States has a culture of promoting participation at the office while maintaining control in the hands of the manager. People in this type of culture tend to be relatively laid-back about status and social standing—but there’s a firm understanding of who has the power. What’s surprising for many people is that countries such as the United Kingdom and Australia actually rank lower on the power distance spectrum than the United States.

In a high power distance culture, you would probably be much less likely to challenge a decision, to provide an alternative, or to give input. If you are working with someone from a high power distance culture, you may need to take extra care to elicit feedback and involve them in the discussion because their cultural framework may preclude their participation. They may have learned that less powerful people must accept decisions without comment, even if they have a concern or know there is a significant problem.

Individualism vs. collectivism

Individualism vs. collectivism anchor opposite ends of a continuum that describes how people define themselves and their relationships with others. Individualism is just what it sounds like. It refers to people’s tendency to take care of themselves and their immediate circle of family and friends, perhaps at the expense of the overall society. In individualistic cultures, what counts most is self-realization. Initiating alone, sweating alone, achieving alone— not necessarily collective efforts—are what win applause. In individualistic cultures, competition is the fuel of success.

The United States and Northern European societies are often labeled as individualistic. In the United States, individualism is valued and promoted—from its political structure (individual rights and democracy) to entrepreneurial zeal (capitalism). Other examples of high-individualism cultures include Australia and the United Kingdom.

Communication is more direct in individualistic societies but more indirect in collectivistic societies. The U.S. ranks very high in individualism, and South Korea ranks quite low. Japan falls close to the middle.

When we talk about masculine or feminine cultures, we’re not talking about diversity issues. It’s about how a society views traits that are considered masculine or feminine. Each carries with it a set of cultural expectations and norms for gender behavior and gender roles across life.

Traditionally perceived “masculine” values are assertiveness, materialism, and less concern for others. In masculine-oriented cultures, gender roles are usually crisply defined. Men tend to be more focused on performance, ambition, and material success. They cut tough and independent personas, while women cultivate modesty and quality of life. Cultures in Japan and Latin American are examples of masculine-oriented cultures.

In contrast, feminine cultures are thought to emphasize “feminine” values: concern for all, an emphasis on the quality of life, and an emphasis on relationships. In feminine-oriented cultures, both genders swap roles, with the focus on quality of life, service, and independence. The Scandinavian cultures rank as feminine cultures, as do cultures in Switzerland and New Zealand. The United States is actually more moderate, and its score is ranked in the middle between masculine and feminine classifications. For all these factors, it’s important to remember that cultures don’t necessarily fall neatly into one camp or the other. The range of difference is one aspect of intercultural communication that requires significant attention when a communicator enters a new environment.

Uncertainty avoidance

When we meet each other for the first time, we often use what we have previously learned to understand our current context. We also do this to reduce our uncertainty. People who have high uncertainty avoidance generally prefer to steer clear of conflict and competition. They tend to appreciate very clear instructions. They dislike ambiguity. At the office, sharply defined rules and rituals are used to get tasks completed. Stability and what is known are preferred to instability and the unknown.

Some cultures, such as the U.S. and Britain, are highly tolerant of uncertainty, while others go to great lengths to reduce the element of surprise. Cultures in the Arab world, for example, are high in uncertainty avoidance; they tend to be resistant to change and reluctant to take risks. Whereas a U.S. business negotiator might enthusiastically agree to try a new procedure, the Egyptian counterpart would likely refuse to get involved until all the details are worked out.

Berger and Calabrese (1975) developed uncertainty reduction theory to examine this dynamic aspect of communication. Here are seven axioms of uncertainty:

- There is a high level of uncertainty at first. As we get to know one another, our verbal communication increases and our uncertainty begins to decrease.

- Following verbal communication, as nonverbal communication increases, uncertainty will continue to decrease, and we will express more nonverbal displays of affiliation, like nodding one’s head to express agreement.

- When experiencing high levels of uncertainty, we tend to increase our information-seeking behavior, perhaps asking questions to gain more insight. As our understanding increases, uncertainty decreases, as does the information-seeking behavior.

- When experiencing high levels of uncertainty, the communication interaction is not as personal or intimate. As uncertainty is reduced, intimacy increases.

- When experiencing high levels of uncertainty, communication will feature more reciprocity, or displays of respect. As uncertainty decreases, reciprocity may diminish.

- Differences between people increase uncertainty, while similarities decrease it.

- Higher levels of uncertainty are associated with a decrease in the indication of liking the other person, while reductions in uncertainty are associated with liking the other person more.

In educational settings, people from countries high in uncertainty avoidance expect their teachers to be experts with all of the answers. People from countries low in uncertainty avoidance don’t mind it when a teacher says, “I don’t know.”

Long-term vs. short-term orientation

The fifth dimension is long-term orientation, which refers to whether a culture has a long-term or short-term orientation. This dimension was added by Hofstede after the original four you just read about. It resulted in the effort to understand the difference in thinking between the East and the West. Certain values are associated with each orientation. The long-term orientation values persistence, perseverance, thriftiness, and having a sense of shame. These are evident in traditional Eastern cultures. Long-term orientation is often marked by persistence, thrift and frugality, and an order to relationships based on age and status. A sense of shame, both personal and for the family and community, is also observed across generations. What an individual does reflects on the family, and is carried by immediate and extended family members.

The short-term orientation values tradition only to the extent of fulfilling social obligations or providing gifts or favors. While there may be a respect for tradition, there is also an emphasis on personal representation and honor, a reflection of identity and integrity. Personal stability and consistency are also valued in a short-term oriented culture, contributing to an overall sense of predictability and familiarity. These cultures are more likely to be focused on the immediate or short-term impact of an issue. Not surprisingly, the United Kingdom and the United States rank low on the long-term orientation.

CRITIQUE OF HOFSTEDE’S THEORY

Among the various attempts by social scientists to study human values from a cultural perspective, Hofstede’s is certainly popular. In fact, it would be a rare culture text that did not pay special attention to Hofstede’s theory. Value dimensions are all evolving as many people gain experience outside their home cultures and countries, therefore, in practice, these five dimensions do not occur as single values but are really woven together and interdependent, creating very complex cultural interactions. Even though these five values are constantly shifting and not static, they help us begin to understand how and why people from different cultures may think and act as they do.

However, Hofstede’s cultural dimensions are not without critics. It has been faulted for promoting a largely static view of culture (Hamden-Turner & Trompenaars, 1997) and as Orr & Hauser (2008) have suggested, the world has changed in dramatic ways since Hofstede’s research began.

Edward T. Hall

Edward T. Hall was a respected anthropologist who applied his field to the understanding of cultures and intercultural communications. Hall is best noted for three principal categories that analyze and interpret how communications and interactions between cultures differ: context, space, and time.

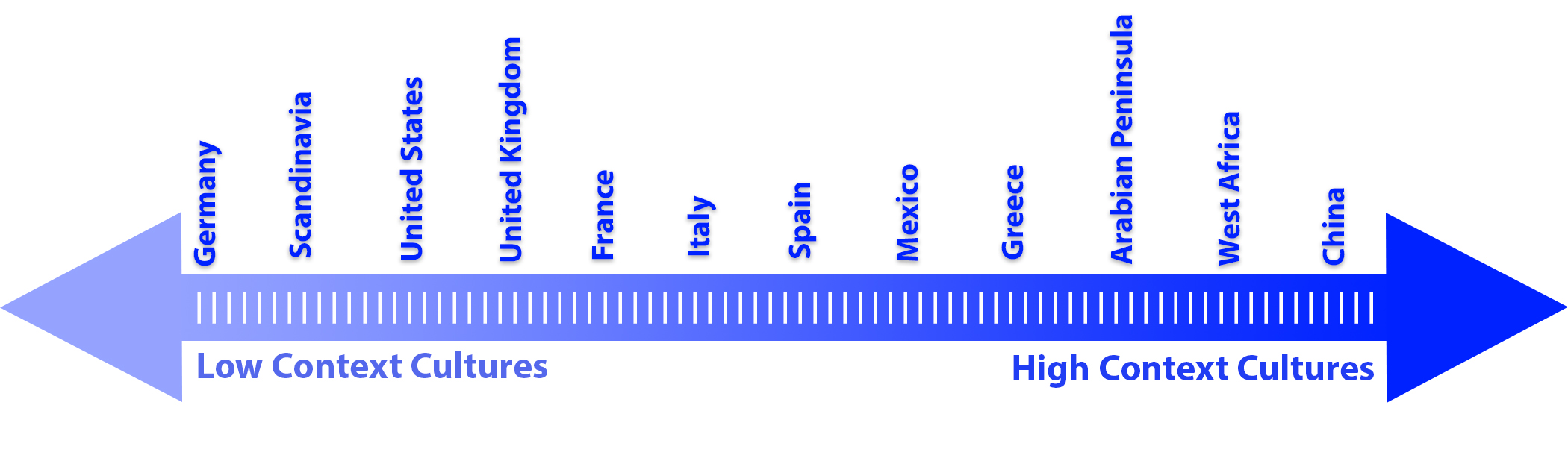

High and low context refers to how a message is communicated. In high-context cultures, such as those found in Latin America, Asia, and Africa, the physical context of the message carries a great deal of importance. People tend to be more indirect and to expect the person they are communicating with to decode the implicit part of their message. While the person sending the message takes painstaking care in crafting the message, the person receiving the message is expected to read it within context. The message may lack the verbal directness you would expect in a low-context culture. In high-context cultures, body language is as important and sometimes more important than the actual words spoken.

In contrast, in low-context cultures such as the United States and most Northern European countries, people tend to be explicit and direct in their communication. Satisfying individual needs is important. You’re probably familiar with some well-known low-context mottos: “Say what you mean” and “Don’t beat around the bush.” The guiding principle is to minimize the margins of misunderstanding or doubt. Low-context communication aspires to get straight to the point.

Communication between people from high-context and low-context cultures can be confusing. In business interactions, people from low-context cultures tend to listen primarily to the words spoken; they tend not to be as cognizant of nonverbal aspects. As a result, people often miss important clues that could tell them more about the specific issue.

Space

Space refers to the study of physical space and people. Hall called this the study of proxemics, which focuses on space and distance between people as they interact. Space refers to everything from how close people stand to one another to how people might mark their territory or boundaries in the workplace and in other settings. Stand too close to someone from the United States, which prefers a “safe” physical distance, and you are apt to make them uncomfortable. How close is too close depends on where you are from. Whether consciously or unconsciously, we all establish a comfort zone when interacting with others. Standing distances shrink and expand across cultures. Latins, Spaniards, and Filipinos (whose culture has been influenced by three centuries of Spanish colonization) stand rather close even in business encounters. In cultures that have a low need for territory, people not only tend to stand closer together but also are more willing to share their space—whether it be a workplace, an office, a seat on a train, or even ownership of a business project.

Attitudes toward Time: Polychronic versus Monochronic Cultures

Hall identified that time is another important concept greatly influenced by culture. In polychronic cultures—polychronic literally means “many times”—people can do several things at the same time. In monochronic cultures, or “one-time” cultures, people tend to do one task at a time.

This isn’t to suggest that people in polychronic cultures are better at multitasking. Rather, people in monochronic cultures, such as Northern Europe and North America, tend to schedule one event at a time. For them, an appointment that starts at 8 a.m. is an appointment that starts at 8 a.m.—or 8:05 at the latest. People are expected to arrive on time, whether for a board meeting or a family picnic. Time is a means of imposing order. Often the meeting has a firm end time as well, and even if the agenda is not finished, it’s not unusual to end the meeting and finish the agenda at another scheduled meeting.

In polychronic cultures, by contrast, time is nice, but people and relationships matter more. Finishing a task may also matter more. If you’ve ever been to Latin America, the Mediterranean, or the Middle East, you know all about living with relaxed timetables. People might attend to three things at once and think nothing of it. Or they may cluster informally, rather than arrange themselves in a queue. In polychronic cultures, it’s not considered an insult to walk into a meeting or a party well past the appointed hour.

In polychronic cultures, people regard work as part of a larger interaction with a community. If an agenda is not complete, people in polychronic cultures are less likely to simply end the meeting and are more likely to continue to finish the business at hand.

Those who prefer monochronic order may find polychronic order frustrating and hard to manage effectively. Those raised with a polychronic sensibility, on the other hand, might resent the “tyranny of the clock” and prefer to be focused on completing the tasks at hand.

What Else Determines a Culture?

The three approaches to the study of cultural values (Kluckhohn & Strodtbeck, Hofstede, and Hall) presented in this chapter provide a framework for a comparative analysis between cultures. Additionally, there are other external factors that also constitute a culture—identities, language, manners, media, relationships, and conflict, to name a few. Coming chapters will help us to understand how more cultural traits are incorporated into daily life.

References: