3.1 Document Design

Designing Reader-Centered Pages and Documents

You build your communications out of visual elements: the dark marks of your words, sentences, and paragraphs against the light background of the page, as well as your drawings and graphs and tables. Your readers see the visual design of these elements before they read and understand your message. And what they see has a powerful effect on the success of your communications, on its usability and persuasiveness.

Here are ways that good design enhances usability.

-

-

- Good design helps readers understand your information.

- Good page design helps readers locate information quickly.

- Good design helps readers notice highly important content.

-

Here are some ways good design affects readers’ attitudes, thereby increasing a communication’s persuasiveness.

-

-

- Good design encourages readers to feel good about the communication itself.

- Good design encourages readers to feel good about the communication’s subject matter.

-

A Reader-Centered Approach to Design

Because page design can have such a significant impact on your communication’s usability and persuasiveness, you should approach design in the same reader-centered manner that you use when drafting text and graphics. Think continuously about your readers, including who they are, what they want from your communication, and the context in which they will be reading.

Design Elements of a Communication

It is helpful to think about the building blocks of a page design in the way that professional graphic designers do. When they look at a page, they see six basic elements:

-

-

- Text: Paragraphs and sentences.

- Headings and titles: Labels for sections of your communication.

- Graphics: Drawings, tables, photographs, and so on — including their captions.

- White space: Blank areas.

- Headers and footers: The items, such as page numbers, that occur at the top or bottom of each page in a multipage document.

- Physical features: These include paper, which may take many shapes and sizes, and bindings, which come in many forms.

-

In Figure 3.1.1 below, notice how your eye is drawn to the blue header and the boxed elements. In these spaces, you can highlight the important parts of your message:

Document Formatting

Most academic and workplace documents are created using Microsoft Office products (Word, Excel, PowerPoint) or Google Docs (G-Suite). These are generally considered industry standards, so it is important that you learn to use them effectively to create professional workplace documents.

Table 3.1 provides some general specifications for many types of technical writing documents:

| MARGINS | Use 1″ margins on all sides (use 2″ when binding) |

| Justify your left margin only; don’t fully justify your paragraphs, as this can result in odd spacing | |

| FONTS | Headings: Sans serif, such as Arial or Calibri |

| Body text: Serif font, such as Times New Roman or Cambria | |

| FONT SIZE | Headings: 12-20 point sans serif font |

| Body text: 11-12 | |

| SPACING | Single-spacing is used for most letters, memos, and emails; 1.5 or double spacing to allow for comments. |

| LENGTH | Paragraphs tend to be no longer than 10 lines |

| Sentences are usually 15-20 words |

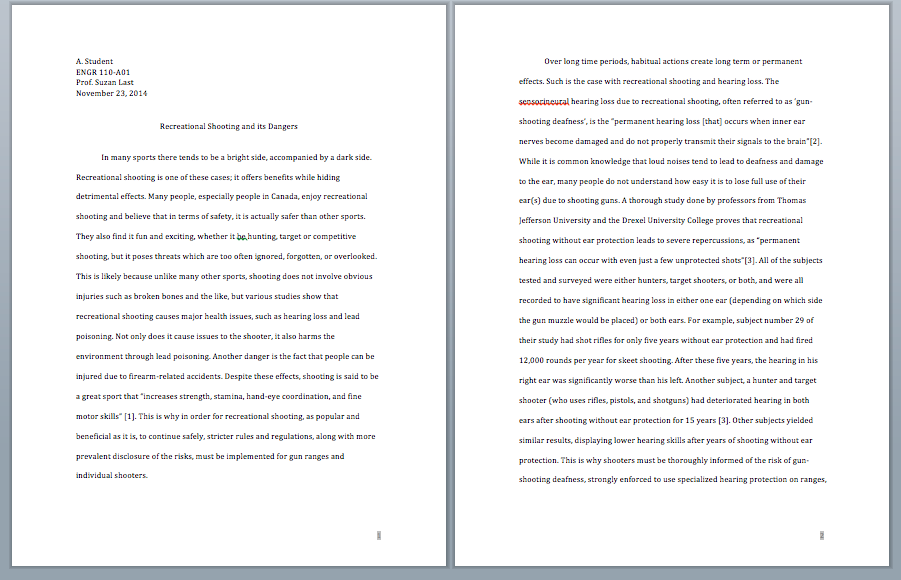

Figure 3.1.2 is an example of the layout for a standard research-style document:

Headings

One of the most useful characteristics of technical writing is the use of headings.

Headings are the titles and subtitles you see within the actual text of much scientific, technical, and business writing. Headings are like the parts of an outline that have been pasted into the actual pages of the document.

Headings are an important feature of technical writing: they alert readers to upcoming topics and subtopics, help readers find their way around in long reports and skip what they are not interested in, and break up long stretches of straight text. They make text easy to navigate and enable the reader to find information they need quickly.

Headings are also useful for you, the writer. They keep you organized and focused on the topic. When you begin using headings, your impulse may be to slap in the headings after you’ve written the rough draft. Instead, visualize the headings before you start the rough draft, and plug them in as you write.

First-Level Headings & Titles

First-level headings are for formal reports with multiple sections (or “chapters”). If you are writing a brief document, start with second-level headings in the body of the document. Follow these guidelines for first-level headings:

-

-

- Make first-levels all-caps.

- Use Roman numerals with first-levels.

- Bold the entire heading including the Roman numeral.

- Make first-levels centered on the page.

- Start a new page whenever you have a first-level heading.

- Begin first-levels on the standard first text line of a page.

-

*Note: Short documents, such as those you write for technical writing classes, typically use a centered title and then start with second-level headings in the body of the document.

Second-Level Headings

Follow these guidelines for second-level headings:

-

-

- Make second-levels headline-style caps (every main word).

- Use bold on second-levels.

- Do not include outlining apparatus such as “A.” or “B.” or “1.” or “2.” with second-levels.

- Make second-levels flush left.

- Leave the equivalent of 2 blank lines between previous text and second-levels.

- Leave the equivalent of 1 blank line between second-levels and the following text.

-

Third-Level Headings

Follow these guidelines for third-level headings:

-

-

- Make third-levels sentence-style caps.

- Use bold for third-levels.

- Either indent third-levels using standard paragraph indentation, or just start third-levels flush left.

- Do not make third-levels a grammatical part of sentences that follow.

- Whether third-levels are indented or not, start all following lines flush left. Don’t indent the entire paragraph.

- Use the standard spacing between paragraphs for paragraphs that contain third-levels.

-

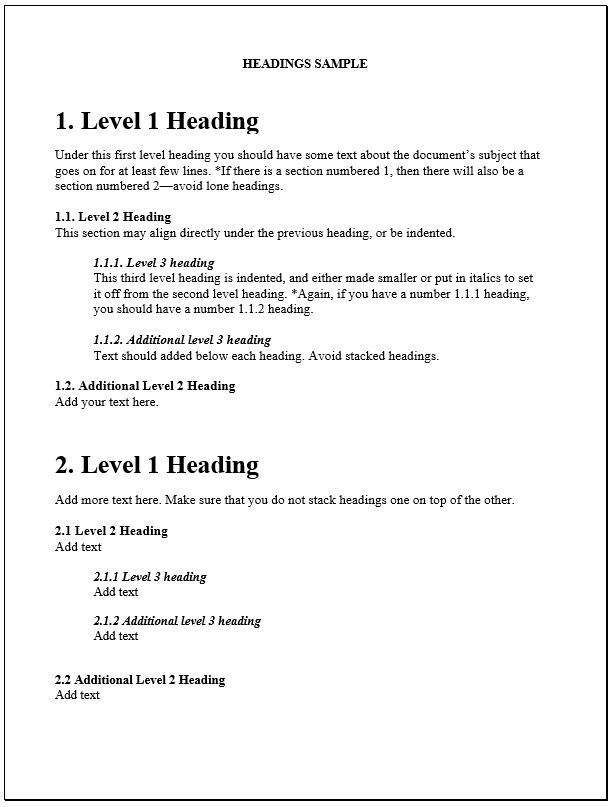

Figure 3.1.3 is an example of a document with first-, second- and third-level headings:

Additional Resources

- “10 Rules of Document Design,” from VirtuallyUntangled.com

- “Business Document Design: Basic Principles for the Contemporary Workplace” (comprehensive video from David Taylor on document design, with specific design instructions for Microsoft Word)

CHAPTER ATTRIBUTION INFORMATION"Page Design." Technical and Business Writing. [License: CC BY-NC-ND] "4.4 Headings." Open Technical Communication. [License: CC BY 4.0] |