1.2 Historical Perspective on Mental Disorders

In our modern world, it is often noted that jails and prisons are the largest treatment providers for mental disorders in the United States; these facilities house and treat far more people with mental disorders than any other psychiatric facility (Chang, 2018). However, it is difficult to put exact numbers to this reality. According to one government report, for example, more than 40% of state and federal prison and jail inmates have some “mental health” problems. This statistic was gleaned from surveys of people in jail and prison, asking if they had been informed by a mental health professional that they had a mental disorder (Maruschak et al., 2021b). These numbers thus fail to count a presumably significant number of people who lack formal evaluation or diagnosis or, for reasons that are easy to imagine, do not answer that jailhouse question truthfully. It also omits people with substance use disorders and other mental disorders that may not be characterized as “mental health” issues, such as learning disabilities.

However, learning disabilities and related disorders are prevalent in custody and should be counted. Nearly a quarter of all prisoners report having a “cognitive disability,” defined as an impairment in thinking, problem-solving, or attention, compared to about 13% of the general population (Maruschak et al., 2021a; Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2023). Similarly, about 25% of prisoners report that they were in special education classes in school, meaning that they were identified in childhood as having a disability that impacts learning (Maruschak et al., 2021a). Again, these self-reported numbers may not be accurate for various reasons, and it is unclear how many people identify as having multiple mental disorders.

In this text, the term mental disorders is used broadly to include mental illnesses, personality disorders, substance use disorders, and diagnoses such as developmental disorders or brain injuries that may impact a person’s functioning.

The presence of large numbers of people with mental disorders in the criminal justice system is a somewhat modern development that is part of the growth of incarceration more generally. Jails and prisons historically held a small fraction of their current population. Over the past 50 years, that population has grown significantly—both overall and for people with mental disorders (Cullen, 2018).

People with mental disorders filling jails and prisons is a real problem on its own, and it is also a slice of a larger problem: the role of the criminal justice system generally—from the point of law enforcement response to community reentry support—in the lives of people with mental disorders. American society and its predecessors have, through time, been unable or unwilling to meet the needs of people with mental disorders—or, often, even properly recognize their humanity. The U.S. criminal justice system is the latest inappropriate landing spot for many people with mental disorders, the culmination of the history outlined in this chapter.

Early Treatment of Mental Disorders

Mental disorders have long been met with negative responses, including denial, fear, frustration, and misinformation. These reactions, dating back to the earliest history of mental disorders, have led to poor treatment of people who experience these disorders. While history is not our primary focus, a look at people with mental disorders over time demonstrates how ignorance and hostility can result in mistreatment. These events are part of our society’s history and set the stage for our current approach to mental disorders.

Prior to the spread of more modern scientific understandings of the brain, mental disorders likely felt especially mysterious and daunting. This led to a common belief in ancient times that mental illness or disability was caused by demonic possession. If someone was “possessed,” treatment might be focused on releasing the “evil spirits” from that person (Szasz, 1960, as cited in Spielman et al., 2020).

The ancient practice of trephination, for example, is believed by some to have been an early way to manage a person who was beset with this kind of problem. Our understanding of trephination is pieced together from archeological finds, including skulls of children and adults on whom the procedure was performed. Trephined skulls have one or more holes drilled in them (figure 1.1). Some researchers believe trephination may have been used to treat seizures, mental illness, or other events that were perceived as signs of demonic presence. The holes may have been intended to allow the release of evil spirits that were causing pain or illness (Spielman et al., 2020). It has been speculated that the procedure may have been done to treat headaches as well, but one would assume those were very bad headaches! Ancient skulls with trephination holes often show signs of healing where the holes were created, suggesting that some who underwent the surgery survived at least for a time—though their condition or quality of life post-surgery is not known (Faria, 2013).

Another ancient treatment option, originating from early Christian beliefs, was exorcism. If a person was experiencing symptoms like delusions or hearing voices, they might be seen as being possessed by the Devil, who was an enemy of God. The Devil then needed to be removed, or exorcized, to help the person recover. Exorcism (pictured in figure 1.2) involved special prayers and rituals conducted by religious leaders (Spielman et al., 2020). Unfortunately, exorcism has sometimes involved abusive or harmful elements as well, resulting in injury or even death for people who, in all likelihood, were experiencing mental disorders (Thomson, 2021).

Although the idea of exorcism dates back to New Testament accounts of Jesus expelling demons from the afflicted, this ritual still exists on the edges of church practices today. In 1999, the Catholic church issued guidelines on how to conduct an exorcism in modern times (Stammer, 1999). When the church created the new exorcism rules, it attempted to make clear that the practice should not be viewed as a cure for mental illness. An exorcist is supposed to consider whether a person needs psychiatric help and perhaps “collaborate” with mental health professionals (Religion News Service, 1999).

Amidst stubbornly problematic practices throughout history, there were also reformers and voices of wisdom when it came to mental disorders, even in ancient times. As early as 500 BCE, for example, the Greek physician Hippocrates had begun to treat mental illness as a disease rather than as a punishment from the gods. Likewise, in the early Middle Ages, Muslim Arabs began creating asylums to care for those with mental illness (Tracy, 2019). Asylums were places intended as a refuge for those with mental disorders, and they later emerged in Europe and America as precursors to mental hospitals and psychiatric facilities (Farreras, 2023). Religious influences on the management of mental disorders remained powerful over time, up until much closer to the modern day.

Mental Disorders in the Middle Ages and Early Modern Era

In the later Middle Ages, around the 11th century, the influence of the Roman Catholic church in Europe had grown very powerful. Natural disasters, such as famine and plague, that occurred during this time were thought to be caused by the Devil. Accordingly, during this same period, religious and spiritual explanations for individual problems, such as mental disorders, increased in popularity. Treatments for mental disorders tended toward prayers, confessions, and atonement, or asking for God’s forgiveness (Farreras, 2023).

Beginning around the 13th century in Europe, religious leaders began spreading the word that certain people—mostly women, and often marginalized women such as widows—were “witches” (History, 2017; Blumberg, 2022). Witches were believed to have formed a pact with Satan himself, rejecting Jesus and the church and posing a threat to those around them (Lewis & Russell, 2024). So-called “witch hunts” during the next several hundred years, culminating in the 15th to 17th centuries, resulted in more than 100,000 people being burned at the stake (Farreras, 2023). Modern historians are not in complete agreement, but many have concluded that at least some of these supposed witches who were so terribly punished were people suffering from some type of mental disorder. Even during the time of the witch hunts, some scholars attempted to argue that the supposed witches were actually mentally ill women, not women possessed by the Devil. However, the Catholic church effectively silenced these voices by banning their writings (Farreras, 2023).

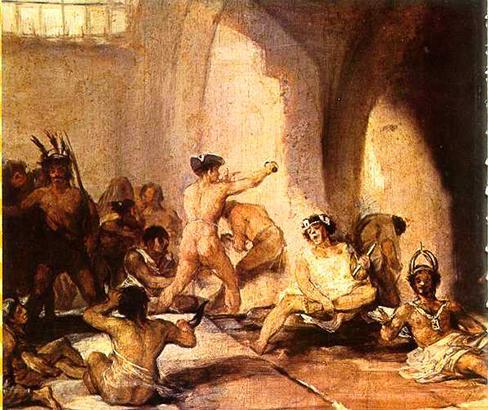

Meanwhile, beginning in the 1600s, as Europe was emerging from the Middle Ages, a first step toward the modern era of treating mental disorders began with the growth of the early institutions often known as asylums. Asylums were purportedly intended to shelter mentally ill people along with other groups, such as poor, unhoused, and disabled people. In reality, as they increased in prevalence, asylums were used to effectively remove undesirable populations from view—protecting the public from asylum occupants—rather than actually helping patients (Farreras, 2023). The conditions inside these early asylums were horrible (figure 1.3).

Two infamous institutions operating in the 1700s and beyond were the Hospital of St. Mary of Bethlehem in London (figure 1.4) and La Salpêtrière, an asylum for women located in Paris that held thousands of patients (figure 1.5). Both of these institutions were essentially dungeons; mentally ill patients were often chained to walls alongside other unfortunate occupants, including the sick and the poor (Tracy, 2019). Asylum patients throughout Europe were sometimes displayed to the public for a fee (Farreras, 2023). It is telling of the conditions in these asylums that London’s Bethlehem hospital was casually called “Bedlam,” a name that gave rise to the modern term “bedlam,” meaning a wild and chaotic situation (Merriam-Webster, n.d.).

To the extent that they were offered in early institutions, treatments for patients with mental disorders were extremely primitive. At the time, the medical response to mental disorders was similar to the treatment of physical illnesses (Farreras, 2023). Bloodletting was one example of an early all-purpose treatment: a care provider would cut a nick in a vein or artery to allow the removal of “excess” blood, supposedly increasing the health of the patient (Cohen, 2023).

Although the conditions in early institutions for people with mental disorders can be hard to fathom, they show us something about how this group of people was viewed. Authorities (including medical, legal, and moral leaders) believed that this group of people lacked the capacity to control themselves and that, along with that inability or lack of “reason,” it followed that they also lacked sensitivity to pain or misery (Farreras, 2023). This is not so different from the startlingly recent belief that infants don’t feel pain—simply because they cannot verbalize or express it in a typically understood or “reasonable” way. This utterly false belief about infants was debunked in recent years with scientific evidence, but even through the 1980s, this misinformation allowed surgeons to operate on young babies without providing any pain relief (University of Oxford, 2015).

Reforming Treatment of Mental Disorders

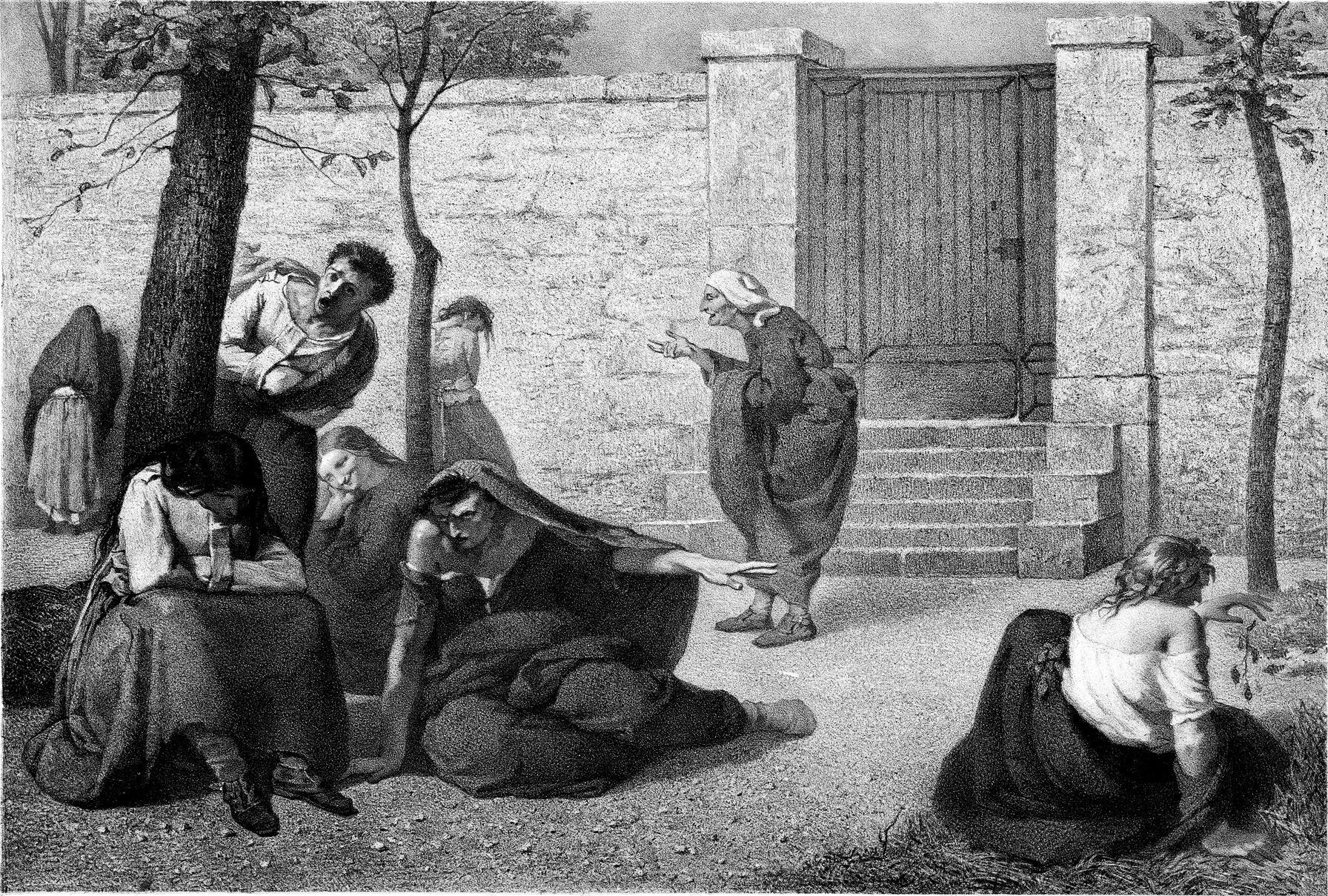

Fortunately, reformers in early 18th-century Europe began thinking differently about the treatment of people with mental disorders. Some doctors began to experiment with less restrictive practices for their patients. In Italy in the late 1700s, the physician Vincenzo Chiarugi began to unchain his patients at St. Boniface hospital in Florence, encouraging them to practice good hygiene and engage in recreational activity. Around the same time in France, physician Philippe Pinel famously unshackled his patients and actually talked to them at the Salpêtrière hospital in Paris (figure 1.6) (Micale, 1985, as cited in Farreras, 2023).

Pinel reportedly engaged in “therapeutic conversations” with patients, talking them through, or out of, their delusions. Although psychiatry was not yet an established medical field and Pinel did not have many appealing options for medical treatment, he did recognize the need for treatment and offered what was available at the time: baths, opium, bloodletting, and occasional laxatives. He saw the occupants of institutions as people in need of care, rather than as dangerous threats to society who needed to be restrained. Pinel, who would later be called the “father of modern psychiatry,” made lasting contributions to the field by improving conditions in the Salpêtrière and providing a model of a new kind of treatment (Tietz, 2021).

Licenses and Attributions for Historical Perspective on Mental Disorders

Open Content, Shared Previously

“Historical Perspective on Mental Disorders” by Anne Nichol is adapted from:

- “Mental Health Treatment: Past and Present” by R. M. Spielman, W. J. Jenkins, and M.D. Lovett, Psychology 2e, Openstax which is licensed under CC BY 4.0.

- “History of Mental Illness” by Ingrid G. Farreras, Noba Textbook Series, Psychology, which is licensed under CC BY-NC-SA 4.0.

Modifications by Anne Nichol, licensed under CC BY-NC-SA 4.0, include substantially expanding and rewriting.

Figure 1.1. Photograph of trephined skull by Wellcome Images is licensed under CC BY 4.0.

Figure 1.2. “Pius Performing an Exorcism” by Lawrence OP is licensed under CC BY-NC-ND 4.0.

Figure 1.3. The Madhouse by Francisco Goya is in the public domain.

Figure 1.4. “Rake’s Progress: Scene In Bedlam” by National Library of Medicine is in the public domain.

Figure 1.5. Armand Gautier’s Madwomen of the Salpetriere by Cushing/Whitney Medical Library is in the public domain.

Figure 1.6. “Pinel, médecin en chef de la Salpêtrière en 1795” by Tony Robert-Fleury is in the public domain.