2.8 Additional Behavioral Considerations

As has been noted throughout this chapter, the vast majority of people who experience mental disorders never find themselves negatively involved in the criminal justice system. This text, of course, is focused on the people who do come into contact with this system, appropriately or not.

Where people with mental disorders do become involved in the criminal justice system, this can be related to maladaptive approaches to getting their needs met – that is, they may engage in harmful or anti-social behaviors. As a professional in the criminal justice field, it is important to be objective and non-judgmental when working with this population, so people impacted by the criminal justice system are not further stigmatized. Some important considerations when working with this population are not diagnoses in the DSM, but they are terms and issues of which you will want to be aware.

2.8.1 Malingering

Malingering occurs where a person fakes or greatly exaggerates symptoms of a medical or mental health condition with a purpose of some sort of personal gain – that is, getting out of a responsibility or attaining some benefit (Psychology Today, 2019). There are many situations where this may occur. A person with a substance use disorder, for example, may falsely report great pain in order to obtain a drug from a medical provider. There are numerous occasions where malingering may occur within the criminal justice system, and some estimates suggest up to 20% of justice-involved people engage in malingering to some degree (Psychology Today, 2019). Malingering may occur in lower-stakes criminal justice situations, such as where a person exaggerates mental health symptoms to attempt to get special housing in a prison or a jail.

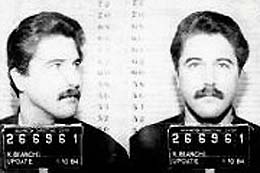

Of greater public concern are situations where a person reports wholly false information during a clinical interview in an attempt to appear mentally ill and avoid responsibility for criminal actions. Successfully avoiding responsibility via malingering is quite rare however, given the caution around malingering and the resistance of the criminal justice system overall to excusing behavior that is attributable to mental disorders (discussed much more in upcoming chapters). An infamous example of an apparent malingerer was Los Angeles’s “hillside strangler” Kenneth Bianchi (figure 2.18) who horribly tortured and murdered at least 10 young women, along with his cousin, in the late 1970s. Though he convincingly claimed to have the rare diagnosis of dissociative disorder, or split personality disorder, Bianchi was disbelieved by skeptical law enforcement officials. Bianchi’s defense story was debunked with a later evaluation, and he eventually pled guilty to his crimes (Biography.com Editors, 2021).

Figure 2.18 shows Kenneth Bianchi in his 1979 mugshot.

2.8.2 Psychopathy

Psychopathy traits are clinically recognized, however psychopathy (like malingering) is not a diagnosis recognized in the DSM-V. Examples of psychopathic traits include: lack of empathy, callousness, deceitfulness, and grandiosity (Burton & Saleh, 2020). It is essential to be familiar with these traits when working in the criminal justice system, where they are found in much higher numbers than in the general population. According to the American Psychological Association, “About 1.2 percent of U.S. adult men and 0.3 percent to 0.7 percent of U.S. adult women are considered to have clinically significant levels of psychopathic traits. Those numbers rise exponentially in prison, where 15 percent to 25 percent of inmates show these characteristics.”

Dr. Robert Hare created the Hare Psychopathy Checklist Revised (PCL-R), a tool that screens for these traits to aid in diagnosis. The tool is essentially a “checklist” of various traits related to an overall “score” of psychopathy. Traits reviewed by the checklist include things like superficial charm and cunningness (Encyclopedia of Mental Disorders, 2023). Generally, the PCL-R is used for forensic populations (i.e. incarcerated people, patients in forensic hospitals, or people involved in the criminal justice system) to determine their level of risk, because people who exhibit these traits are more likely to engage in criminal activity. Clinical professionals with an advanced degree can complete specialized training to administer the PCL-R (Hare, n.d.).

2.8.3 Criminality

Criminality includes the thinking and behavior that a person engages in that supports criminal conduct. This can be a complicated term for professionals working in the criminal justice field. Generally, professionals acknowledge that people who become entangled in the criminal justice system have experienced very high rates of trauma in their lives, from many sources. Additionally, people who are justice-involved often have developed deeply ingrained behaviors and thoughts, for many reasons, that contribute to a criminal lifestyle. Those who work in the criminal justice system recognize the criminality itself is often a symptom to acknowledge and treat – even as other mental disorders or traits are being addressed. Well-informed professionals appreciate the “both/and” nature of some of the conduct they are addressing: people may be responding to trauma, dealing with mental disorders, etc., and they are engaging in maladaptive behaviors and cognitions that lead them further into criminal patterns. There are many curriculums and treatment modalities that incorporate and acknowledge criminality, alongside other conditions that people in the justice system may experience and for which they may need support.

2.8.4 Licenses and Attributions

“Additional Behavioral Considerations” by Kendra Harding is licensed under CC BY 4.0.

Figure 2.18. Kenneth Bianchi mugshot by Los Angeles Sheriff’s Department is in the Public Domain.