9.3 The Role of Civil Commitment

Over time, our society has come to recognize that people with mental disorders—like other people—enjoy individual rights and personal liberties. People do not automatically forfeit their rights to freedom and autonomy when they experience illness or disability. Rather, rights must be compromised only in extreme circumstances, for important reasons, and with adequate protections in place.

As you will recall from the history of mental disorders and the development of laws related to mental disorders in Chapter 1 and Chapter 3 of this text, the existence of rights for people with mental disorders was not always self-evident. The laws related to civil commitment help ensure that people who are experiencing mental illness and disability are not confined or forced into involuntary treatment improperly—merely because of their diagnosis or because they are more vulnerable. Civil commitment has rightfully taken its spot as a “last resort” option in the mental health continuum of care.

9.3.1 Commitment as a Threat to Freedom

The prospect of commitment raises important questions about the competing goals of safety and individual liberty:

- When is it appropriate to restrict the freedom of a person for something that is merely threatened, but has not yet happened? On the other hand, when is it appropriate to allow a situation to unfold where people may be hurt?

- More specifically to the topic of this text, are we pleased to have a mechanism to help a person avoid engaging in potential criminal activity? Or are we troubled by treating a person, in some ways, like they have committed a crime—when they have not?

Scholars, medical and legal professionals, and disability and mental health communities have struggled with these questions. Opinions differ on how best to strike a balance and identify what takes priority: a person’s need to receive care and treatment for a serious mental disorder that threatens health and safety—or the person’s right to decline treatment and move about the world as desired—even if that desire is influenced or compromised by a mental disorder (figure 9.3).

Figure 9.3 (1) & (2) includes pictures of an indoor cat on a bed and an outdoor cat on the move. Both freedom and confinement have benefits, even for our beloved pets. For people, of course, the issues and contrast are much more weighty and complex.

As stated by one prominent scholar considering the issue of civil commitment, “Patients should not die with their rights on. But they should not live with their rights off, either.” (Hoffman, 1) In other words, it is troubling to think of someone sacrificing their life or health for an abstract “right” to liberty, yet it is also troubling to consider that a life preserved via involuntary care may lack the freedom that most of us consider essential to a good life. Do we allow a sick or disabled person to “die with their rights on,” or do we intervene, perhaps maintaining safety and life, but at the expense of freedom, forcing this vulnerable person to “live with their rights off?”

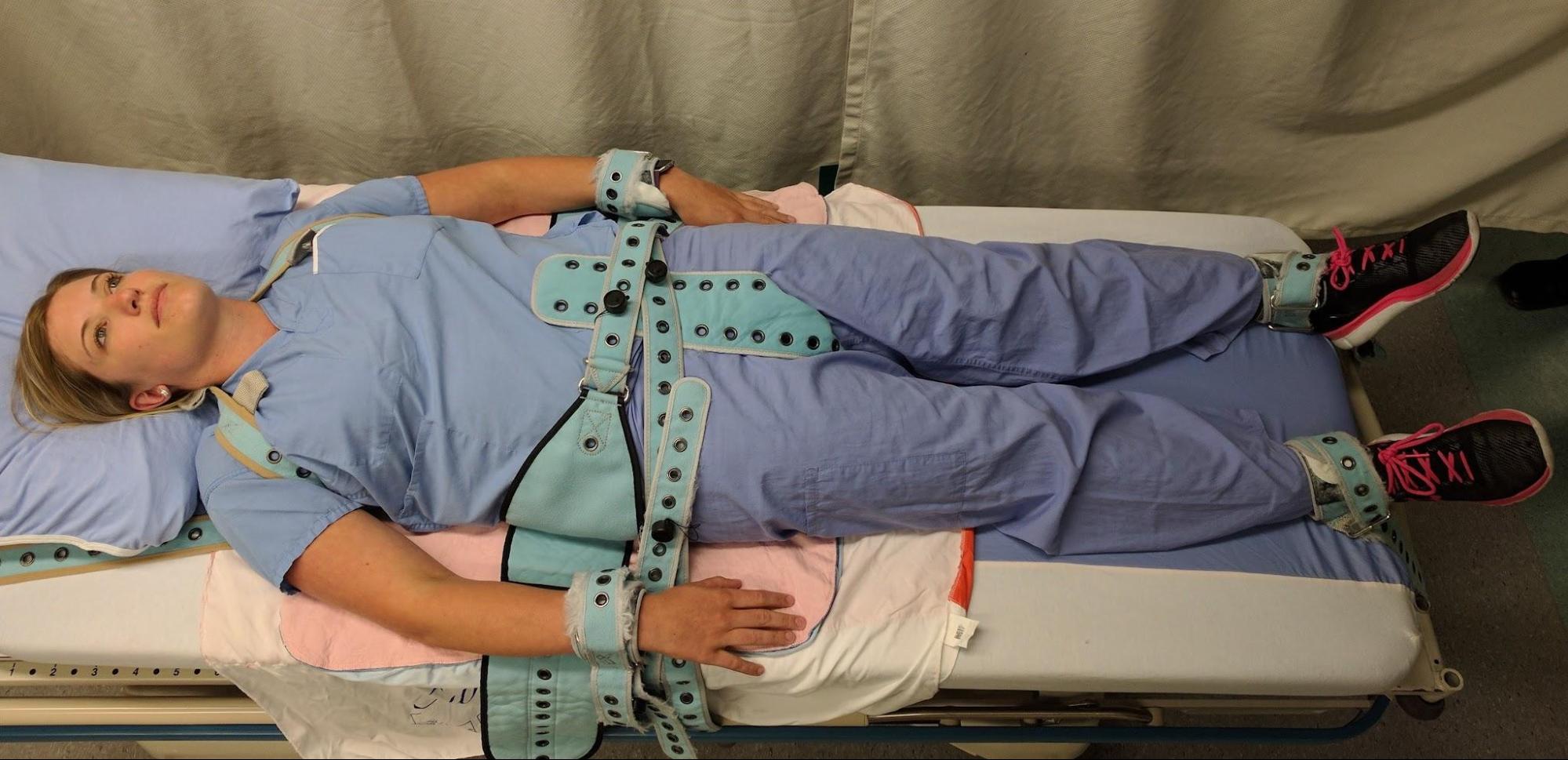

These are not simply theoretical or legal questions, either. To be forced into a hospitalization at a point of serious illness and extreme vulnerability is traumatic and damaging. In the words of one writer offering her own first-person account of civil commitment: “Unless you have experienced it, I don’t think you can fully comprehend what it means to lose autonomy over your own body (figure 9.4), or to have to ‘earn the privilege’ of 30 minutes of fresh air and sunshine” (Sangree, 2022).

Figure 9.4 pictures a person in Pinel restraints, a tool used in medical settings when patients are behaving dangerously. Restraints are a last resort, but seeing them in use, especially in a medical setting, feels a bit shocking and emphasizes the serious loss of autonomy that can occur in a medical hold.

A further challenge in determining the right “balance” between competing concerns of freedom and safety is the impact of inappropriate factors, like racism, sexism, and ableism, on these determinations. For example, studies looking at civil commitment populations have found clear racial bias in involuntary commitment trends: “Patients of color [are] significantly more likely than white patients to be subjected to involuntary psychiatric hospitalization, and Black patients and patients who identified as other race or multiracial [are] particularly vulnerable, even after adjustment for confounding variables” (Shea et al., 2022). When freedom and autonomy are generally valued less for a particular group—as has been the case for Black people, women and those with mental disorders in America—the concerns around involuntarily committing members of these groups in their “best interest” should be heightened.

9.3.2 Commitment as a Safety Measure

While limits on civil commitment are critically important for protection of those with mental disorders, it is also true that many observers and participants in this system experience legitimate frustration at the seeming unavailability of this tool. Legal and mental health professionals, as well as first responders, may naturally want to prevent harm or stop problems from materializing. A county attorney advocating for civil commitment, for example, has only this route to intervene prior to a person experiencing a severe deterioration in health and safety. If the person comes back to the courthouse as a criminal defendant, after civil commitment was denied, that can be seen as a system failure. If a goal is to avoid criminalizing mental disorders, then shouldn’t civil commitment be used more often?

Community and family members may share similar feelings of frustration (or fear, or sadness) as they try to prevent a loved one from becoming very sick, or from acting in ways that might bring them harm or send them into the criminal justice system. Disability advocates may express concern on both sides of this issue. There is concern about government overreach in civil commitment – but also concern for the loss of dignity a person may experience prior to reaching a court-recognized level of deterioration. Before being eligible for commitment, a person may experience a great deal of loss from destroyed relationships, jobs, support systems, and other critical pieces of a stable life. Should we really allow it to go that far? Should the standard for stepping in with help be lower?

This issue is closely connected to the problem of criminalization discussed in Chapter 4. Ideally, people choose and have access to treatment in the community – but sometimes they can’t effectively access treatment. The criminal justice system can quickly become an alternative source of care, absorbing people who did not qualify for involuntary treatment in a civil process and so become criminally involved: arrested, charged, and confined. As we have learned, vastly more people receive mental health treatment in the criminal system than anywhere else. Objections to this state of affairs range from financial (it’s expensive) to practical (jail is a horrible place to provide mental health care) to ethical (it is simply wrong to criminalize mental disorders). Again, this begs the question: should civil commitment be an easier hurdle? Is the difficulty of obtaining commitment a source of the criminalization problem?

Courts have wrestled with all of these questions, and they face the conundrum of how speedily and confidently to require involuntary treatment for people with mental disorders. Decisions by courts responding to these questions provide us with some Constitutional guidance around civil commitments. However, the issues and questions presented in this section are not easily or finally resolved.

As you watch the 6-minute video linked at figure 9.5, think about the commitment process reviewed there and the requirements to qualify for civil commitment. As you consider the perspectives of Eric’s mother, frustrated that her son was not committed, and the perspective of Lorene, who faced civil commitment herself, what do you think is the proper role of civil commitment? What important perspectives are missing from this clip?

Figure 9.5 is a local news outlet’s story about the status of civil commitment practices in Oregon. If you are interested in more details about the stories introduced in this shorter clip, you may want to follow up by watching the longer piece Uncommitted report produced by KGW news [Website/video].

9.3.3 The Role of Civil Commitment: Licenses and Attributions

“The Role of Civil Commitment” by Anne Nichol is licensed under CC BY 4.0.

Figure 9.3. (1) Photo of cat in window from Pixabay; (2) Photo of cat outdoors from Pixabay.

Figure 9.4. Photo of person in pinal restraints by James Heilman, MD, CC BY-SA 4.0 <https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/4.0>, via Wikimedia Commons

Figure 9.5. What it takes for a patient to be committed involuntarily by KGW News is licensed under the Standard YouTube License.