1.4 Modern Developments: The Decline of Institutional Treatment

Significant changes to the American approach to mental disorders, and to the status quo of institutionalization, had already began to occur in the 1940s. President Harry Truman signed the National Mental Health Act in 1946, leading to the creation of the National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH) a few years later. Over the next decades, the NIMH significantly expanded America’s commitment to use science to understand and treat mental illness (National Institute of Mental Health, 2021). Scientific progress would, eventually, lead to opportunities for treatment of mental disorders outside of hospitals.

The idea of asylums, and state hospitals, had been to provide care via a sheltering environment, which necessarily removed people with mental disorders from their communities. Also, while primitive brain surgeries and shock therapy had many drawbacks, one practical one was that these treatments could not be accessed in the community – recipients were required to be hospitalized. Thus, a most revolutionary scientific development in treating mental disorders was the development of psychiatric medications. Unlike previous procedures and treatments that could only be performed in hospital settings, medications that treated mental disorders could be used in the community. And, where severe symptoms might have required confinement of patients, medications to control symptoms of mental illness alleviated that need for confinement. Just as many activists were beginning to question the routine institutionalization of people with mental disorders, medication management provided an opportunity to end this approach.

1.4.1 SPOTLIGHT: The Oregon State Hospital, Then and Now

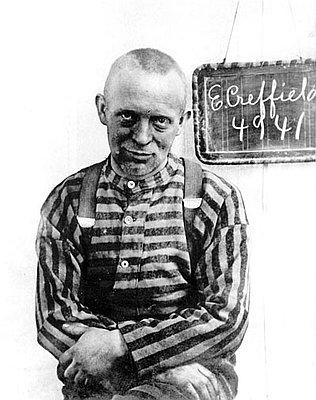

After Corvallis-area cult leader Edmund Creffield (figure 1.13) was convicted on charges of adultery, most of the members of the Brides of Christ Church were committed to what was then called the Oregon State Insane Asylum in Salem. The diagnosis was “religious hysteria,” and the women were committed by concerned family members. The year was 1904, and the Asylum had only been in operation since 1883.

Figure 1.13. Edmund Creffield, shown in an Oregon State Penitentiary photo around 1904. Feel free to learn more about Creffield’s fascinating story [Website].

The Oregon State Insane Asylum was, at the close of the 1800s, considered a safe place for people to take their family members for many reasons, in addition to supposed insanity. Some had committed crimes, others were developmentally disabled, and many others may have simply been seen as a burden to society. A report released by the Oregon State Insane Asylum in 1896 listed the various “causes for insanity” among those admitted between December 1894 and November 1896. Among these reasons were things such as business trouble, financial trouble, loss of sleep, menopause, and even masturbation (Mental Health Association of Portland, 2012).

Purportedly, asylum patients could receive treatment and rehabilitation, and then return back to society. Unfortunately, a mental institution’s idea of “treatment” back in the 1800s and early 1900s was often more detrimental than helpful, and many abuses occurred. Among these treatments were lobotomies, ice baths, electroshock therapy, straightjackets, sedation, and forced sterilization.

By the middle of the 20th century, it became apparent that the Oregon State Insane Asylum wasn’t large enough to house all of the Oregonians in need of inpatient mental health services. By 1958, the facility was vastly overcrowded with 3,545 patients, causing already-horrific conditions to be even worse. This led to the opening of several new mental health facilities around the state, and the Asylum officially changed its name to Oregon State Hospital. For more history, photos and stories from the Oregon State Hospital, you may be interested in exploring the website of the hospital’s fascinating Museum of Mental Health [website].

Fortunately, as science and medicine have made advances, so has our understanding of effective treatments for mental disorders. Psychiatric facilities such as the Oregon State Hospital no longer administer lobotomies or any of the other horrific “treatments” that were once the norm. Treatments for mental disorders now often include medications, supplemented by individual and group therapies and activities.

As discussed in more depth in the main text, psychiatric hospitals that remain in operation have improved vastly since the time of their inception. However, the overall mental health system in the United States, including Oregon, has floundered since deinstitutionalization, or the widespread closure of the old version of these hospitals. Recognizing the inadequacy of community mental health supports, Oregon has renewed its commitment to this population – at least for the moment. In the 2021-2022 legislative session, Sen. Kate Lieber and Rep. Rob Nosse passed large investment packages for Oregon’s behavioral health system (Porter, 2022). With any luck, these investments and resulting services will ensure those Oregonians who need care and social support will be able to access them.

In 1949, lithium was introduced as the very first effective medication to treat mental illness, specifically what is now known as bipolar disorder (Tracy, 2019). Another critical breakthrough occurred in 1952, when the first antipsychotic medication, chlorpromazine, became publicly available. Antipsychotic medications treat psychosis, a debilitating aspect of mental illness that impacts a person’s ability to distinguish what is real. People experiencing psychosis (discussed further in Chapter 2 of this text) may have delusions, where they believe something that is not real, or hallucinations, where they see or hear things that do not exist. Antipsychotic drugs treat and help control these symptoms – allowing a person to again perceive reality (National Institute of Mental Health, 2022). Chlorpromazine, marketed and more commonly known as Thorazine, effectively (though not completely) controlled symptoms of psychotic illness in many patients (Tracy, 2019).

Fueled by the scientific successes of the late 1940s and 1950s, as well as the growing activism against institutional treatment of mental disorders, the Community Mental Health Act (CMHA) was passed by Congress in 1963. President John F. Kennedy, whose sister had undergone a lobotomy twenty years earlier, signed it into law (figure 1.14). The CMHA promised federal support and funding for community mental health centers (National Institutes of Health, 2013). This legislation (along with some of the other laws discussed in Chapter 3 of this text) was intended to change how services for mental disorders were delivered in the United States. Specifically, the CMHA meant to shift mental health care to communities, bringing patients along to live safely in those communities.

Figure 1.14. President John F. Kennedy signs the Community Mental Health Act into law in 1963. Oregon Representative Edith Green is in the background with other lawmakers.

The signing of the CMHA was done with hope and good intentions for reducing institutionalization of all people with mental disorders – those with mental illness as well as people with intellectual and developmental disabilities. In a speech to Congress promoting his agenda, President Kennedy described a plan that would change the landscape for people with mental disorders:

I am proposing a new approach to mental illness and to mental retardation. This approach is designed, in large measure, to use Federal resources to stimulate State, local and private action. When carried out, reliance on the cold mercy of custodial isolation will be supplanted by the open warmth of community concern and capability. Emphasis on prevention, treatment and rehabilitation will be substituted for a desultory interest in confining patients in an institution to wither away.

John F. Kennedy, Special Message to the Congress on Mental Illness and Mental Retardation, February 5, 1963 (Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, 2021).

(Mental retardation was the medical term that predated the modern and preferred terms intellectual disability or intellectual developmental disorder. As retardation became used as a slur, drawing on the nearly universal societal disdain for people with intellectual disability, the term was rejected by disability self-advocates, and eventually the general public, as well as the legal and medical establishments (Social Security Administration, 2013).)

The CMHA anticipated the building of 1500 mental health centers in communities, which would allow half of the nearly 600,000 people with mental disorders who were then institutionalized in state hospitals to be treated, instead, in their homes and communities (Erickson, 2021). While the CMHA did help connect many people with community-based treatment, and psychiatric hospitalizations decreased drastically in the ensuing years, the law did not meet its full promise. Only half of the expected mental health centers were ever built, and funding proved inadequate for the ones that were created. Though the CMHA provided dollars to build the mental health centers, it did not provide continuous funding to run them, expecting states to step up with support. States, though, were quick to reduce their own contributions when funding was tight or other priorities were more politically popular (Smith, 2013).

Critics argue that the CMHA was an example of “optimism without infrastructure” (Erickson, 2021). The CMHA was well-intentioned, hopeful even, but there were failures in executing its plans; in the end, not nearly enough community support was available for people to quickly leave institutions, or to get the help they needed when they did leave. This was particularly true for people with more serious or severe mental disorders.

1.4.2 Modern Developments: The Decline of Institutional Treatment: Licenses and Attributions

“Modern Developments: The Decline of Institutional Treatment” by Anne Nichol is licensed under CC BY 4.0.

Spotlight: The Oregon State Hospital: Then and Now” by Monica McKirdy is licensed under CC BY 4.0.

Figure 1.13. Photo of Edmund Creffield at Oregon State Penitentiary, by Oregon State Penitentiary is in the Public Domain

Figure 1.14. John F. Kennedy by Cecil Stoughton is in the Public Domain