1.6 Mental Disorders Post-Deinstitutionalization

Today, the horrific asylums that were a part of America’s earlier history no longer exist. Now, state hospitals are actually psychiatric hospitals run by state governments, and they are not simply repositories for unwanted people. These hospitals offer, and are focused on, short-term care. People are hospitalized only if they are an imminent threat to themselves or others – not simply because they have a mental disorder. (Spielman, Jenkins & Lovett, 2020) Lengthy psychiatric hospitalizations occur only under specific circumstances and with careful safeguards, as discussed in Chapter 9. People are not legally locked up in institutions simply because they experience a mental disorder.

In the wake of deinstitutionalization, many people with mental disorders were able to live happier and more fulfilling lives, with increased dignity and independence, than would have been possible during the heyday of state hospitals. These are people who were able to secure sufficient housing, treatment, and community supports; for these people and their loved ones, deinstitutionalization was an enormous victory.

1.6.1 Inadequate Community Alternatives

However, the story of deinstitutionalization is not an entirely happy one. Lack of adequate community opportunity, care, and support for people with mental disorders has led to new challenges. There are not enough community-based mental health centers, and they are often inadequate. Funding is an often-cited issue, but underfunding is not the only problem. Staffing is a challenge as well – with not enough dedicated professionals entering and staying in critical behavioral health fields. A recent government report from Oregon, which is understood to have a very high rate of unmet community mental health needs, outlines numerous issues: inadequate workforce overall; low numbers of providers of color in all workforce roles, depriving consumers of culturally responsive care; and poor work environments due to low pay, unmanageable workloads, and workplace stress – all of which lead providers to exit the field (Center for Health Systems Effectiveness, 2022).

The shortage of practitioners is not the only barrier to providing community services. Mental health staff may not be adequately trained, or have the resources, or find collaborative partners to handle the needs of people with severe mental illnesses. There is often no provision made for the other services people require to be able to access mental health care: housing, food, and job training (Spielman, Jenkins & Lovett, 2020).

Hardest hit by system failures are people who already have additional barriers to success – including people of color, immigrants, and others. Populations who, even in the best of circumstances, are likely to face discrimination in accessing community services, housing, and education, had greater challenges post-deinstitutionalization in making their homes in the community (Deas-Nesmith & McLeod-Bryant, 1992). Homelessness and criminal engagement – the topic of this text – are significant risks for underserved groups (Spielman, Jenkins & Lovett, 2020).

1.6.2 Links to Homelessness and Incarceration

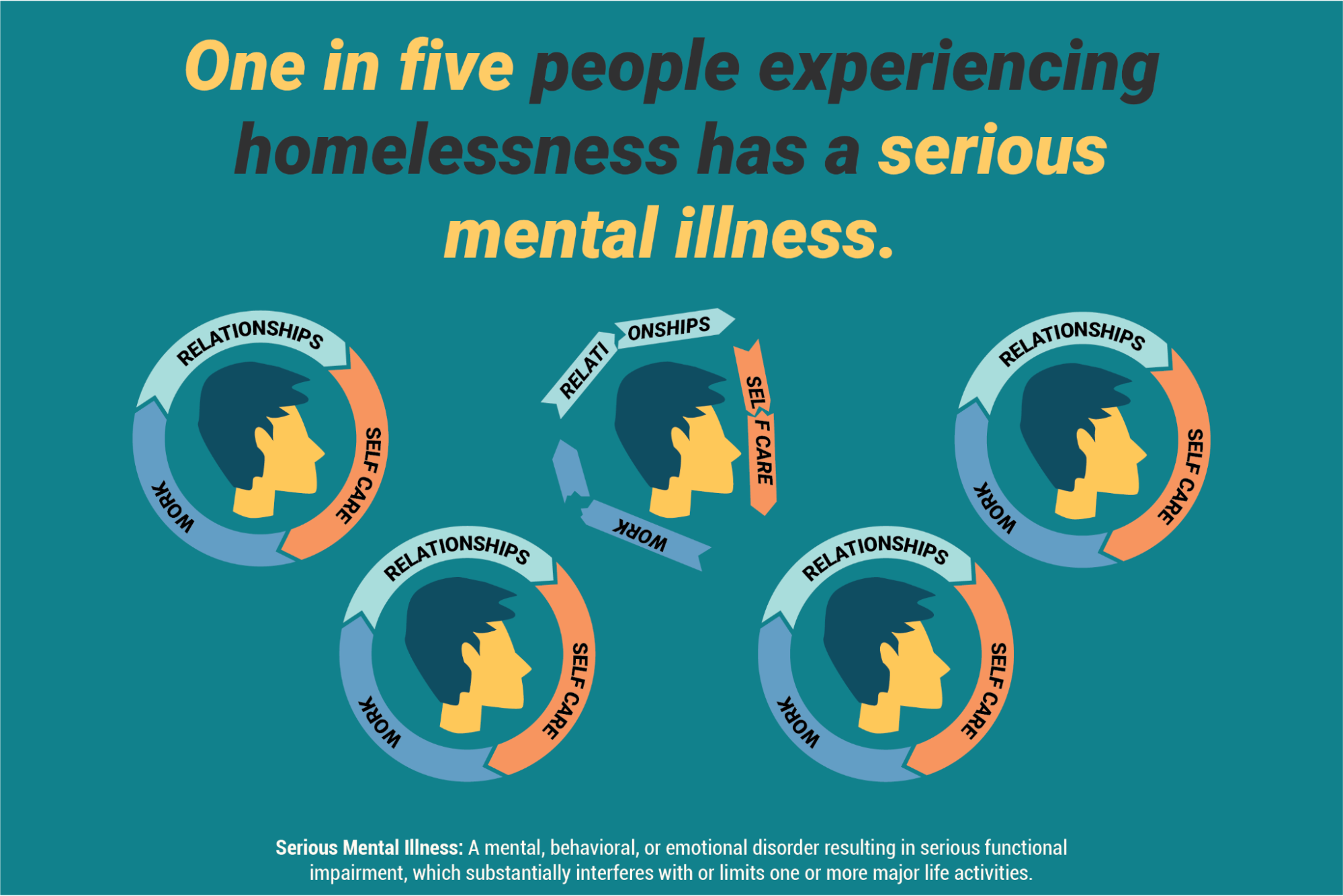

Some observers, noting the current housing crisis, along with overflowing jails and prisons, are quick to blame deinstitutionalization for many of these problems. Indeed, a large portion of the homeless population has one or more mental disorders. An estimated 20-30% of houseless individuals have a serious mental illness such as schizophrenia (figure 1.19), and a startling 50% have traumatic brain injuries – far beyond the numbers found in the general population (Padgett, 2020). Likewise, jails and prisons began to fill to overflowing around the same time state hospitals were emptying, and these institutions are now the largest providers of mental health services in America.

Figure 1.19 illustrates a conservative estimate from the federal government suggesting that one in five homeless individuals experience serious mental illness that greatly impacts their capacity to sustain relationships, work, and self-care.

Other observers will point out that deinstitutionalization did not cause homelessness, nor deprive people of mental health treatment in their communities. Rather, the initial wrong that had to be righted was institutionalization. Then, shortages of care, housing and other services followed. Also, stigma, the persistent and unfounded negative reputation surrounding people with mental disorders, constantly contributes to the marginalization of this population. It is harder for people who experience mental illness or disability to find housing, get jobs, and otherwise succeed. Denial of these opportunities based on a person’s disability status may be illegal, but it is common and persistent (Ponte, 2020).

The deinstitutionalization movement also did not require the growth of jails and prisons. In fact, the “war on drugs” of the 70s and 80s, and the “get tough on crime” movements of the 80s and 90s are more direct causes of mass incarceration in America. The supposed shift of people directly from state hospitals into jails and prisons is sometimes referred to as transinstitutionalization, a hypothesis suggesting that the same group of people simply moved from one institution (hospitals) to another (prisons). However, while people with mental disorders are disproportionately found in jails and prisons, this is for many complicated reasons that go beyond the simple assumption that a person with mental illness simply had to be moved from one institution to another. (Prins 2011)

In addition to the reasons for increased incarceration discussed above, there is the factor of continued or repeated incarceration. Studies indicate that people with mental disorders get “stuck” in jail and prison significantly longer than other people: they are denied pretrial release more frequently and they receive longer sentences more often. Additionally, once in prison, people with mental disorders are often not provided with adequate or effective treatment, leading them to fail to qualify for parole, which keeps them in prison. Or, if released untreated, people with mental disorders are more likely to “fail” upon release; they are at high risk of reoffending and cycling back into the criminal justice system (Ponte, 2020).

There is also strong evidence that simply putting more people into psychiatric hospitals is a very expensive reaction that would not actually significantly decrease the number of people with mental disorders in the criminal justice system. Rather, solutions like providing housing and other community supports are far more effective in preventing criminal system involvement. (Prins, 2011).

1.6.3 Mental Disorders Post-Deinstitutionalization: Licenses and Attributions

“Mental Disorders Post-Deinstitutionalization” by Anne Nichol is licensed under CC BY 4.0.

Figure 1.19. “Unmet Behavioral Health Needs” by The Bureau of Justice Assistance is in the Public Domain.