3.2 Overview of Federal Disability Law

In Chapter 1 of this text, you were able to see how historical attempts to eradicate mental disorders, and the mistreatment and confinement of people with mental disorders, came to be challenged by both evolving social ideas and by scientific and legal developments that helped make change possible. As social activists were criticizing overflowing state hospitals, the development of psychiatric medications and the passage of the Community Mental Health Act in 1963 were making it increasingly possible for people with mental disorders to function outside of hospitals. Together, these forces led to the reduction and closure of institutions that resulted in an increase of people with mental illness and disabilities living in American communities.

Though the movement towards deinstitutionalization in the 1960s (discussed in Chapter 1) signaled the end of routine confinement of people with mental disorders, there was still a lot of work to do. People with disabilities of all sorts had limited opportunities to achieve financial or other forms of independence. Discrimination, the categorical exclusion based on a person’s status, was perfectly legal when based on disability. People with disabilities had no right to an education and were often excluded from jobs, housing, and services like restaurants or stores. A person who used a wheelchair, for example, often could not get in the door of businesses, use public transportation, or find accessible toilets. Some barriers were especially burdensome to those with mental disorders; for example, students with any type of disability did not have to be accommodated at (or even admitted to) public schools, and medical insurance did not cover mental health needs.

Over the next several decades, more progressive thinking about people with disabilities, coupled with a growing body of legislation and court decisions, began to change the outlook for people with mental disorders. As part of the disability rights movement in the 1970s and beyond, advocates fought to end discrimination, and to achieve access and inclusion, for people with all sorts of disabilities, including mental disorders. Advocacy was not enough, though. Laws were needed – and they were eventually passed – to provide a legal basis for people with disabilities to fight discrimination and demand access to education, workplaces, recreational settings, transportation, health care, and more.

The timeline here provides an overview of these legal highlights. Links are provided for your information if you would like to learn more about a particular piece of legislation:

3.2.1 SPOTLIGHT: Timeline of Important Disability Laws

1956 – Social Security Act amended [Website]: This law provided new monthly benefits to disabled workers over 50, and allowed benefits for disabled children of workers, even after the child was over 18.

1963 – Community Mental Health Act (CMHA) [Website]: This JFK-driven legislation provided federal funding for development of local/community mental health resources with the intent to shift care from institutions to home. See more information about the CMHA in Chapter 1.

1964 – Civil Rights Act [Website]: This landmark law prohibited discrimination based on race, religion or national origin. This law did not protect people with disabilities, but it provided a model for eventual legislation recognizing the civil rights, or personal legal rights, of disabled people.

1965 – Medicaid [Website]: This part of the Social Security Act provided some coverage of medical expenses for people with disabilities.

1973 – Section 504 of Rehabilitation Act [Website]: This Act was the first legal recognition of the civil rights of disabled people. It prohibits recipients of federal funds (hospitals, government offices, schools) from denying access to or discriminating against disabled people. This law is still used to allow students with disabilities, including mental disorders, to demand access to schools via “504” plans. The federal government resisted implementing this law until protests forced them to do so in 1977.

1975 – Education for All Handicapped Children Act: This law provided, for the first time, that children with disabilities (including those caused by mental disorders) are entitled to public education alongside non-disabled peers. It was renamed Individuals with Disabilities Education Act (IDEA) [Website] in 1990.

1980 – Civil Rights of Institutionalized Person Act (CRIPA) [Website]: This law gives the federal Department of Justice the power to sue state and local authorities when there is a pattern of rights being violated in an institutional setting (prisons, juvenile facilities, nursing homes, state hospitals). An example would be a prison repeatedly denying required mental health care to inmates.

1988 – Fair Housing Amendments Act [Website]: This law expanded the 1968 Fair Housing Act, which prohibited race discrimination in housing sales and rentals, to include a prohibition on disability discrimination.

1990 – Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA) [Website]: The ADA was a civil rights law modeled after the Civil Rights Act, and it prohibited discrimination and required large parts of American society to increase accessibility. Discussed in detail later in this Chapter.

1996 – Mental Health Parity Act (MHPA) [Website]: This law required insurance plans to offer the same level of coverage for mental disorders as physical disorders. This law was strengthened in 2010 by the Affordable Care Act [Website], which requires most insurers to offer mental health and substance use treatment coverage.

1996 – Air Carrier Access Act (ACAA) [Website]: This Act fills in a hole left by the ADA, forbidding discrimination based on disability in air travel.

2008 – ADA Amendments [Website]: Amendments to the ADA resolved disputes among the courts by clarifying that certain mental disorders (including intellectual disability, bipolar disorder, depression) were included “disabilities” under the law.

(Accessibility.com, 2022; College of Education and Human Development, Institute on Disabilities, 2022; Georgetown, 2016; Social Security, n.d.)

As the above timeline shows, some of the most important laws, especially the earlier ones, focused on the financial support of people with disabilities. These laws (Social Security, the CMHA, and Medicaid) were first steps in allowing a degree of independence and community opportunity for people with a variety of disabilities. Though it was an enormous and celebrated step to prohibit discrimination against people based on race and sex, the Civil Rights Act of 1964 did not address discrimination based on disability. Discrimination against people who experienced mental disorders and other disabilities remained legal and unchecked for many more years.

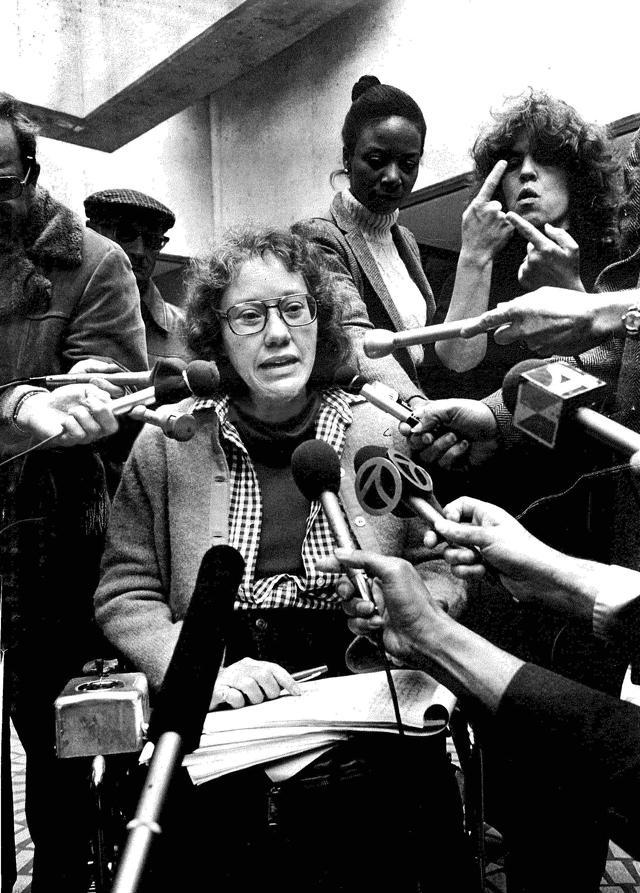

Section 504 of the Rehabilitation Act, known as “Section 504,” was the very first law that recognized the civil rights of people with disabilities. The language in Section 504 prohibited discrimination against disabled people by the federal government and by state entities receiving federal funding (U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, 2006). The law was passed by Congress in 1973, in what was reportedly an “under the radar” insertion of revolutionary language into an otherwise uncontroversial act. Once it became clear that the new law would have a huge impact (requiring places like government buildings to become accessible, for example), three Presidents (Nixon, Ford, and Carter) resisted signing the regulations needed to put the law into action. Focused advocacy, culminating in a month-long “sit-in” at a federal office building in San Francisco, along with shorter sit-ins in other locations, protested the delay. The San Francisco protest was led by a group that included Judith Heumann (figure 3.1), introduced in Chapter 1 of this text, and her friend Kitty Cone, another disability activist involved in the Berkeley Center for Independent Living. As a child, Heuman, a wheelchair user, had been denied entry to kindergarten as a “fire hazard” – only the first of many times she faced discrimination. Kitty Cone, who had muscular dystrophy, had already been active in protesting race and gender discrimination when she became involved in the disability rights movement in the 1970s (figure 3.2). An openly gay woman, Cone faced additional discrimination based on her gender and sexuality (Disability Rights Education & Defense Fund, n.d.).

Figure 3.1. Activist Judith Heumann, alongside prominent disability rights attorney Barbara Ransom, is pictured here in 2019.

Figure 3.2 LGBTQ disability activist Kitty Cone, who helped organize the Section 504 protests.

Supporting the Section 504 demonstrations, including the federal building sit-in, were another group of experienced civil rights activists, the Black Panthers. This group had formed to empower Black people, especially in protest against police brutality, and they now lent their voices, skills and power to the disability rights movement. Longtime Black Panther party leader Bradley Lomax (figure 3.3) had developed multiple sclerosis, which gave him a personal view into the myriad challenges of being a disabled Black man in America.

Figure 3.3. Bradley Lomax, center, a member of the Black Panther party and a disability rights activist, is pictured next to activist Judith Heumann at a rally in 1977 at Lafayette Square in Washington.

Lomax’s personal experience drew him to the disability rights movement. When he joined the Section 504 protests, along with a few other disabled Black activists, he inspired the involvement of other Black Panthers. The Panthers kept showing up to feed and supply the disabled protesters stuck in the federal building for their nearly month-long protest. The Panthers were a critical source of support for the Section 504 sit-in (Connelly, 2020; Thompson, 2017). And, according to Kitty Cone, the disability protestors felt a strong connection with the Black activists who had inspired them and now supported them: “we felt ourselves the descendants of the civil rights movement of the ’60s” (Cone, n.d.).

In the face of the lengthy protests and other pressure by the disabled community and their allies, Section 504 regulations were finally implemented, and the law went into effect in 1977. Once enacted, Section 504 applied only to select federally funded entities, not state or private ones, but its reach was incredibly significant. As noted, this law was the first to establish the civil rights of people with disabilities, prohibiting discrimination and exclusion based on disability. Section 504 began to be used – and is still often used – to secure access to public school for children with a range of disabilities, including mental disorders. It allows children, via a “504 plan” to get basic accommodations to overcome barriers. For example, a typical 504 plan might provide for breaks in the school day to help a child manage an anxiety disorder so that they can participate in school. Section 504 is often viewed as the law that allows children with disabilities to get in the door – and stay – at school. Most importantly, Section 504 served as something of a “warm-up” for the later laws discussed here – especially the Americans with Disabilities Act.

The Education for All Handicapped Children Act (1975), later renamed the Individuals with Disabilities Education Act (IDEA), was passed in its original form just a few years after Section 504. The IDEA established “special education” services for children who experience disabilities (including mental disorders) that impact their ability to learn and function in school. While Section 504 might allow a child to be at school, the IDEA actually requires that they be provided with an education at school.

The IDEA requires that the government provide a “free and appropriate” public education (FAPE) to all disabled children – just as is provided to nondisabled children. Plans for the education of the disabled child must be outlined in a document called an individualized educational plan, or IEP. The IDEA explicitly disfavors segregation of children due to disability, preferring that all children be educated together where possible (figure 3.4). Today, school systems regularly engage in the segregation of disabled children and families still must advocate for appropriate and inclusive education in light of their child’s disability, but, prior to the passage of Section 504 and the IDEA, children with disabilities quite simply had no right to public education at all.

Figure 3.4 shows a child receiving individual support from an adult in a classroom.

Other laws displayed in the Spotlight timeline above – the inclusion of disabled people specifically in the Fair Housing Act of 1988, as well as the Mental Health Parity Act and the Air Carrier Access Act, both passed in 1996 – are remarkable for staking out basic opportunities for people with disabilities (housing, air travel, and health insurance) in very recent history. Likewise, the Americans with Disabilities Act (the ADA), which is discussed in detail in the next section, was passed in 1990. The year 2008 in the United States is better known for the election of Barack Obama as president, but it was also the year that the ADA was amended to ensure protection for people with most mental disorders (such as mental illness or intellectual disability) or brain-related disorders (such as epilepsy).

3.2.2 The Criminal Justice System in Context

You may wonder, how does access to education, employment, and other activities relate to our topic of people with mental disorders in the criminal justice system? People who find themselves being processed in the criminal justice system were not always there, and most will not always be there. The same people found in the criminal justice system are (or were) also involved in the educational system; they may have been employed (or wish to be); they ride buses and trains; and they live in neighborhoods. These community experiences are intertwined with their eventual involvement in criminal justice. How people are treated and supported in their communities impacts whether or not they will find themselves engaged in the criminal justice system. You can imagine many examples of this connection but, as one example, we know that lack of school success due to unmet educational needs is an enormous risk factor for juvenile or criminal system involvement, and this effect is even more pronounced for children with less social privilege, such as students of color or students in the foster care system (Leone et al., 2003).

Likewise, those who work in the criminal justice system – whether they are law enforcement officers, lawyers, corrections staff, or any other role – are all part of our larger society. Their view of people with disabilities, including mental disorders, is shaped at home and at school, and refined as they continue into adulthood. If, for example, a young student is led to believe that people with mental disorders do not belong or are not welcome in typical classrooms at school, how might that same person, now a law enforcement officer, treat a vulnerable person with a mental disorder that they encounter in the course of their work? Will that officer understand that the person with a mental disorder is deserving of respect and entitled to inclusion in their community, and that they need accommodations to do so? Alternatively, if a victim advocate has ridden the bus to work every day alongside a neighbor who experiences an intellectual disability, might that advocate be more able to appreciate the needs of a similarly situated person who appears in their office, needing help? Though the specific focus in this textbook is the criminal justice system, that system has to be considered in the context of our larger society, of which it is both a part and a product.

3.2.3 Overview of Federal Disability Law: Licenses and Attributions

“Overview of Federal Disability Law” by Anne Nichol is licensed under CC BY 4.0.

Figure 3.1.“Judy Heumann and Barbara Ransom” by Bailey Hill is licensed under CC BY-SA 4.0

Figure 3.2 Photo of Kitty Cone by The Center for Independent Living is included under fair use.

Figure 3.3 Photo of Bradley Lomax with Judith Heumann by HolLynn D’Lil. Used under fair use.

Figure 3.4 Photo of child in school by Mikhail Nilov is licensed under the Pexels license.