5.4 Guidelines for Encounters

Encounters with people with mental disorders are not necessarily more likely to escalate into violence than are encounters with people without mental disorders. It is a common misconception that people with mental disorders are more violent, generally, than people who do not experience mental disorders. In fact, people with mental disorders are not more violent. People with mental disorders and developmental disabilities need to be treated with compassion, patience and support when trying to convey information. It is never the goal to escalate situations, the goal should always be to use techniques to de-escalate situations wherever possible.

5.4.1 De-Escalation

De-escalation, or reduction in intensity or conflict, is an essential technique in the criminal justice field, where professionals are likely to consistently find themselves in tense and stressful, and even dangerous, situations. The goal of de-escalation is to bring a person back to their baseline, and away from an intense state where they may be unreasonable and unpredictable – due to panic or anger or other triggers, so that use of physical force is not required.

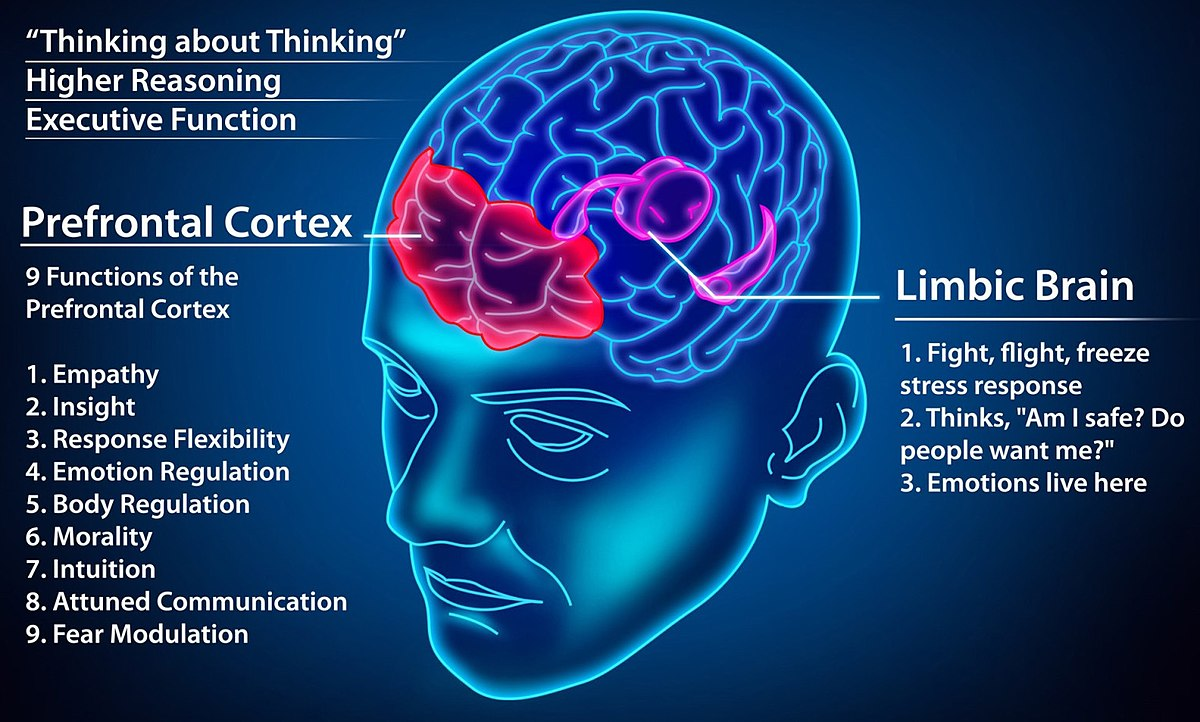

The first step in de-escalating a situation is to remain calm. Using your breath and your own coping skills to maintain a sense of calm will go far. People absorb external, escalating stimuli which causes their prefrontal cortex (i.e. rational brain that helps us make decisions and solve complex problems) to turn off. What is left to function is a person’s amygdala (i.e. fight, flight, or freeze part of the brain). When someone’s amygdala is activated, they cannot make rational decisions until their prefrontal cortex comes back online. The goal of de-escalation is to use skills to calm the amygdala and reactivate the reasonable prefrontal cortex (figure 5.6).

Figure 5.6 shows the prefrontal cortex or the higher reasoning part of one’s brain and the limbic brain, which is the part of the brain that functions for survival in a stressful situation.

De-escalating a situation – as you are sharing your calmness with a very upset person – requires that you use assertiveness skills, that may include both physical and verbal assertiveness.

Physical assertiveness is generally taught as displaying a strong posture, firm stance, and open body language. Interacting with a panicked or very angry person is not the time to fold your arms together, slouch down, cross your feet, or divert your eye contact. It is a time to display calm body language, but also demonstrate authority. This approach includes being mindful of your movements and being sure to not raise hands above waist level or make sudden movements.

Physical assertiveness is also positioning yourself for safety. Throughout your career, it is very important to always be aware of your exits when meeting with someone where the situation could potentially escalate. You should always be closest to an exit and know how to re-position for safety if a situation escalates. For instance, if someone is becoming out of control when meeting in an office setting, move to safety by slowly making your way to the door. You can also position yourself so that a piece of furniture is between you and the person who may be a threat.

Verbal assertiveness is maintaining a sense of calm, and helping control a situation, with your voice. You may need to raise your voice initially to get an escalated person’s attention (e.g. call out their name), and then slowly bring your voice down, so the person must lower their voice in order to hear you speak. Verbal assertiveness includes using clear and short sentences with some form of directive. A directive to give to an escalated person may be, “I need you to step out of the doorway and let me pass.” It may also be something more direct to maintain your safety. For example, “put the knife down and step away from the kitchen.” When someone is in a heightened emotional state, they cannot comprehend complex sentences or complex problem solving; short sentences and precise directives can go far when working to deescalate a situation, verbally.

After skills have been used to effectively de-escalate a situation, it is important to rest and take care of yourself. De-escalating someone can be time-consuming and emotionally exhausting for the person tasked with de-escalating the encounter. Your body will have likely had an emotional and physical response to being around an escalated person, which could leave you tired and feeling drained. All these feelings are common after responding to an escalated situation (City of Portland, n.d.).

Most de-escalation training is, naturally, taught by and for men – who still make up the vast majority of law enforcement professionals. Women make up less than 15 percent of full time law enforcement officers in the United States (Van Ness, 2021). Commenters have observed that women may more naturally tend to deescalate situations, perhaps stemming from the physical reality that most cannot actually muscle their way out of confrontations and may be socialized throughout their lives to work as peacemakers. Female-presenting officers may more naturally rely on their voices, their reason, and their empathy to deescalate situations. These techniques may look and feel different in some ways from those discussed above – which are traditionally used and passed along in the current male-dominant law enforcement culture. Some advocates suggest that a substantial increase in women on police forces might be critical to truly changing the culture of policing. Women officers are statistically less likely to use excessive and deadly force than male officers, and so are male officers who work alongside them (Naili, 2015). However, even where police increase their female employees, racial disparities in arrests and other measures are not improved (Corley, 2022). In order to be truly effective, deescalation strategies need to be developed, and provided to officers, with the traits of the individual officer in mind, as well as the traits (gender, culture, disability status) of the person with whom they are working.

Specific de-escalation techniques and approaches may be helpful in dealing specifically with people in crisis due to mental disorders, and some of these approaches are the focus of Crisis Intervention Training (CIT), discussed in the previous section. These approaches encourage human connections and empathy. Watch the video linked here, at figure 5.7, sharing the experience of officers engaged in this training.

Figure 5.7 is a news report about CIT de-escalation training. As you watch, note the methods used to build empathy among the officers. Do you believe this may be an effective approach?

5.4.2 Use of Force

Use of force situations are the last resort when de-escalation encounters have been unsuccessful. Most law enforcement agencies have use of force policies. These policies describe an escalating series of actions an officer may take to resolve a situation. This continuum generally has many levels, and officers are instructed to respond with a level of force appropriate to the situation at hand, acknowledging that the officer may move from one part of the continuum to another in a matter of seconds.

An example of a use-of-force continuum follows:

-

Officer Presence — No force is used. Considered the best way to resolve a situation.

- The mere presence of a law enforcement officer works to deter crime or diffuse a situation.

- Officers’ attitudes are professional and nonthreatening.

-

Verbalization — Force is not-physical.

- Officers issue calm, nonthreatening commands, such as “Let me see your identification and registration.”

- Officers may increase their volume and shorten commands in an attempt to gain compliance. Short commands might include “Stop,” or “Don’t move.”

-

Empty-Hand Control — Officers use bodily force to gain control of a situation.

- Soft technique. Officers use grabs, holds and joint locks to restrain an individual.

- Hard technique. Officers use punches and kicks to restrain an individual.

-

Less-Lethal Methods — Officers use less-lethal technologies to gain control of a situation.

- Blunt impact. Officers may use a baton or projectile to immobilize a combative person.

- Chemical. Officers may use chemical sprays or projectiles embedded with chemicals to restrain an individual (e.g., pepper spray).

- Conducted Energy Devices (CEDs). Officers may use CEDs to immobilize an individual. CEDs discharge a high-voltage, low-amperage jolt of electricity at a distance.

-

Lethal Force — Officers use lethal weapons to gain control of a situation. Should only be used if a suspect poses a serious threat to the officer or another individual.

- Officers use deadly weapons such as firearms to stop an individual’s actions.

Using any form of force is by all means a last resort. Many trainings are taking place across many police departments with an emphasis on crisis intervention, mental health awareness, and de-escalation techniques. A police officer’s verbal skills are going to be one of the most important skills to utilize and are by far the most frequently used. A big focus is placed on enhancing verbal communication in heightened situations to prevent more physical interactions on the use of force continuum.

5.4.3 Guidelines for Encounters Licenses and Attributions

DPSST Section attributed by Ashley Anstett.

De-escalation section attributed by Kendra Harding. Pieces of this section was learned through Portland Police Bureau Women Strength Programs developed by Sara Johnson (Introductory Self-Defense Classes | Class Schedules | The City of Portland, Oregon (portlandoregon.gov))

Behavioral Health Unit | Portland.gov

Use of Force: Copied verbatim from: National Institute of Justice, “The Use-of-Force Continuum

For Police, a Playbook for Conflicts Involving Mental Illness – The New York Times (nytimes.com)

Learning | Bureau of Justice Assistance (ojp.gov)

Brain image (CC-BY-4.0)File:Blog prefrontal cortex.jpg – Wikiversity

Figure 5.6 “Trauma brain” by Jan Edmiston, A Church for Starving Artists is licensed under CC-BY-NC-SA 3.0.

Figure 5.7 Police officers take course teaching de-escalation techniquesyou tube license