6.3 Competency Determinations

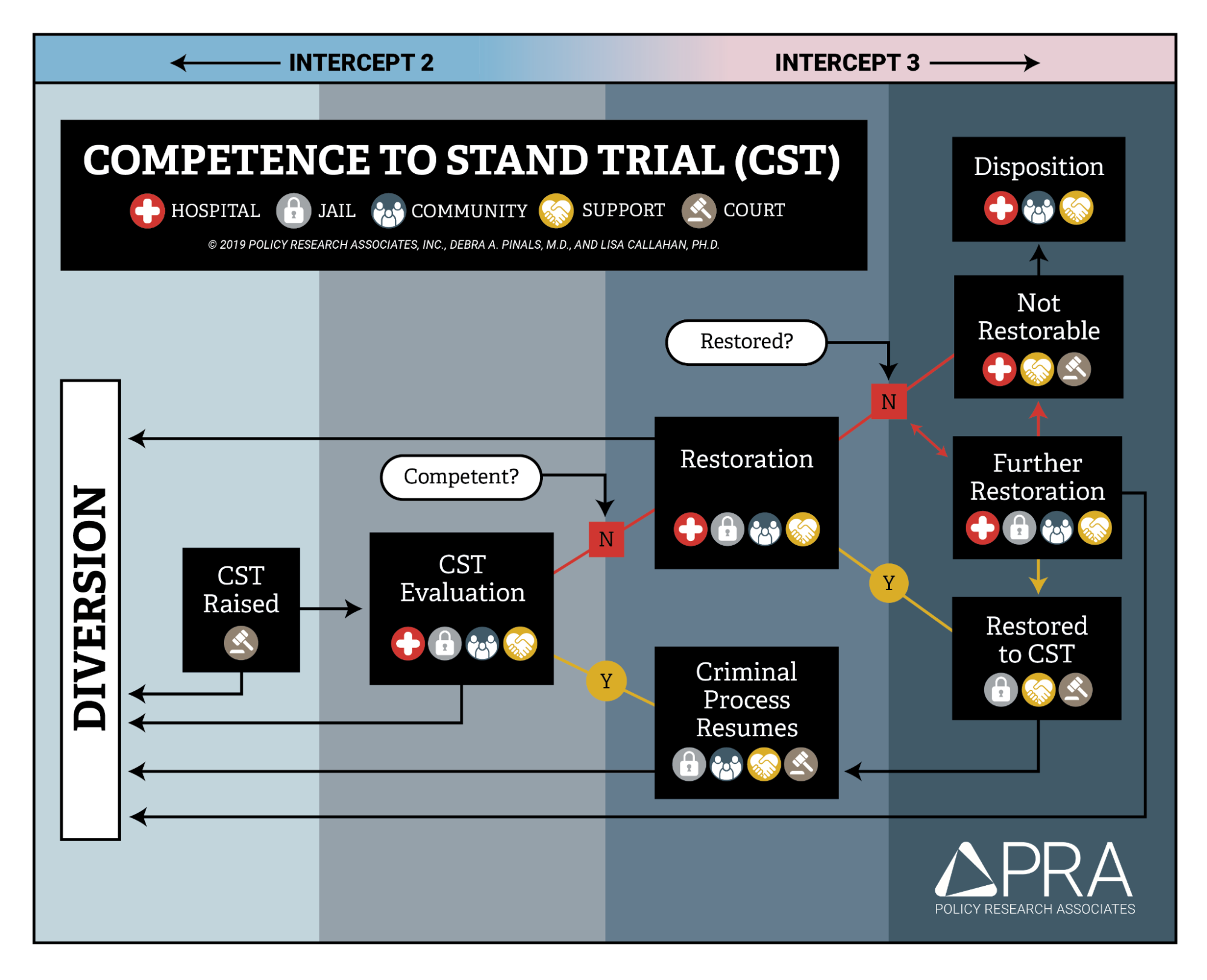

Competence is not just a legal principle; it is something that must be ensured for each individual in the criminal courts. If a serious question is raised about a defendant’s competence, the defendant must be evaluated by a mental health professional to determine their ability to proceed and advise the court on required next steps (figure 6.4, Pinals & Callahan, 2019). In our example case, Jose Veguilla’s new defense attorney, at that very first hearing, recognized that Mr. Veguilla was likely not competent. The attorney objected to the case moving forward at all. The judge did complete the hearing, formally advising Mr. Veguilla of his charges, and then ordered Veguilla to be sent to a psychiatric hospital for a formal evaluation of his competence to stand trial (Thompson, 2023).

Figure 6.4 shows the progression of the “aid and assist” or competence process, from the point of the issue being raised, to evaluation, then restoration (if necessary and if possible) and eventual return to the criminal process. Note that the corresponding Intercepts for diversion, discussed in detail in Chapter 4, are indicated at the top of this flowchart.

6.3.1 Assessing Competence

When an accused person is clearly very ill or disabled, and wholly unable to comprehend the reality of their situation, it may seem obvious that they are not competent to proceed with their case in court. This would seem the situation for Jose Veguilla, who suffered from severe dementia. It would likewise seem true for any defendant who is extremely impaired by a mental disorder, for example, a defendant operating on delusional beliefs, such as insisting that they are an undercover operative in a military action, rather than a defendant on trial. Nonetheless, a competency determination has enormous legal impact, with the power to halt a murder trial, and so it must be made with care, based on the evidence and the law.

The key piece of evidence in a competency determination is usually a court-ordered evaluation of the defendant. A typical competency evaluation is performed by a licensed mental health professional, generally a psychologist or psychiatrist. The evaluator considers the person’s mental capability, in light of the legal standard for competence in the relevant jurisdiction, and then offers a professional opinion as to whether the person is legally competent.

A good competency evaluation would include a number of pieces of information that support the evaluator’s competency conclusion and allow a reviewing judge to use the evaluation as the basis for a legal decision:

- a mental status exam, looking at whether the person has basic orienting facts, such as who and where they are;

- a description of psychiatric symptoms the person is experiencing, such as loss of memory, hearing voices or having delusional beliefs;

- an assessment of the person’s understanding of the criminal proceedings, including their knowledge of the charges against them, possible outcomes in court, and perhaps the pros and cons of engaging in a plea agreement.

It is best practice for competency evaluations to explicitly address whether the evaluator believes that the person is making up or exaggerating symptoms for some benefit, e.g. avoiding criminal processing, which is known as malingering (discussed in Chapter 2).

To think about how a competency evaluation process looks in practice, imagine a defendant who has bipolar disorder and is symptomatic in the midst of a manic episode (see discussion of bipolar disorder in Chapter 2). The defendant might meet the requirement of factually understanding the proceedings against them, but their racing thoughts, delusional beliefs, and overall uncontrolled emotions might prevent them from working effectively with their defense attorney. The defendant might be unable to track discussions about their case, or be constantly trying to fire their attorney. The defendant’s active mental illness may prevent them from behaving in an orderly way that would allow them to attend their courtroom proceeding. In this case, the evaluator may state their opinion that the person is not competent to proceed and needs treatment to gain competence.

Each state’s practices vary in terms of their competency proceedings, and the federal system has its own separate set of rules. But competency procedures everywhere must – at a minimum – protect a defendant’s due process rights according to the federal Constitution. Ideally, procedures protect the safety of the public and the defendant, while maintaining the integrity of the criminal justice system. Oregon examples are provided here for purposes of illustration.

In Oregon, the law governing competency determinations is Oregon Revised Statute 161.370 [Website], and the process is formally called a “Determination of Fitness to Proceed.” You can click the link provided, and other links to Oregon statutes in this section, if you are interested in seeing the statutory language. The evaluation performed as part of an Oregon court’s determination is often called either an aid and assist evaluation or a “370 evaluation” based on the local statute number. Consideration of malingering (or “faking”) is required by Oregon law (Or. Admin. R. 309–090–0025).

If an Oregon criminal defendant “lacks fitness to proceed,” court proceedings halt, leaving the parties with several options and requirements for moving the case forward. Or. Rev. Stat. §161.370(2). Among the available options listed in the Oregon statute are:

- pausing to “restore” the accused person’s competence (discussed later in this chapter);

- completely dismissing the charges against the person; and/or

- beginning the process of hospitalizing the person for involuntary mental health treatment, or civil commitment, which is discussed in Chapter 9 of this text.

If the defendant is evaluated and found competent to proceed, they will remain either in jail custody or in the community and proceed with their criminal case.

6.3.2 Restoration of Competence

You have learned that the mere presence of a mental disorder does not prevent a person from being arrested or charged with a crime, though diversion opportunities (discussed in Chapter 4) may offer police or prosecutors an alternative to criminal proceedings in some cases. If a person is headed to criminal court however, lack of competence is a complete bar to continuing the case; an accused person cannot go forward to trial or any other resolution unless or until they are found competent to do so. The process of treating a person with the objective of making them competent, or able to aid and assist, is referred to as restoration of competence (figure 6.5).

Figure 6.5 shows a provider providing therapeutic services to a small group. Restoration can involve an array of services aimed at getting a person to the point of competence to resolve their legal case.

Restoration involves targeted treatment to take the accused person from an irrational or confused state to one of adequate understanding of the criminal process and their particular situation. Some people are not good candidates for restoration. The elderly dementia patient Jose Veguilla, who we have discussed throughout this chapter, cannot be made competent, as several professionals have opined; rather, his memory and ability to aid and assist in his defense worsens over time as his dementia progresses. This presents a particular problem that is discussed further in Chapter 9 of this text: the defendant who is never able to proceed (Thompson, 2023).

Most defendants, however, are better suited to competency restoration. For example, the competency evaluation imagined in the previous section involved a mental health professional who found that a defendant experiencing mania lacked the ability to aid and assist their attorney. In this type of case, restoration should strive to help or correct in the areas of deficit identified by the evaluator (e.g. racing thoughts, delusional beliefs, and attention span). Restoration is specifically meant to help the person meet the Dusky qualifications so that they can proceed to trial or other resolution of their case.

Restoration treatment is not focused on the overall mental health of the person, though it often requires psychiatrically stabilizing the person with medication and therapy. If psychiatric symptoms, such as voices, delusions, or mania are preventing a person from meeting the standard of competence, those symptoms need to be targeted in restoration treatment. If the person refuses medication that is necessary for restoration, medication treatment may be forced under some limited circumstances. Sell v. United States, 539 US 166 (2003).

Another part of competency restoration treatment is the teaching of legal terms and concepts. For example, a person may be instructed about the role of their lawyer; what confidentiality means; what a judge and jury do; and other general information about the criminal justice system. In its fact sheet on the topic, the Oregon State Hospital, for example, describes restoration as potentially including other therapeutic services: occupational therapy to work on daily living skills (cooking and managing personal finances); educational services; and medical and dental services (figure 6.6; Oregon Health Authority, 2019). Restoration takes place most often in state psychiatric hospitals, such as the Oregon State Hospital, where it is generally referred to as treatment under a “370 order,” again referring to Oregon’s particular competency statute.

In Oregon, as well as other jurisdictions, people with serious mental disorders who are accused of crimes can get “stuck” – unable to resolve charges against them as they face a series of delays triggered by questions about their competence. For example, a person may wait in jail for potential resolution of their case, which becomes impossible due to competency questions; they then await transfer to a hospital for a competency evaluation, only to return to jail and then wait again for competency restoration if ordered. Defendants such as Jose Veguilla can become “stuck” in another way – experiencing a mental disorder that wholly defies restoration to competence, yet facing charges that no victim or prosecutor is likely to want to dismiss or set aside. Commitment to a psychiatric hospital for restoration of competence is discussed in Chapter 9 of this text, along with other types of civil commitments.

Figure 6.6. The Oregon State Hospital in Salem is where evaluation and treatment for restoration of competence occurs, as well as care for people found Guilty Except for Insanity (GEI) of felony-level offenses, in the state of Oregon. All states have public psychiatric facilities that serve similar roles.

Restoration can occur outside of the hospital as well. In Oregon, as in most other states, the law provides for restoration in the community under the supervision of mental health providers, rather than in a hospital setting, if that can be done safely. Or. Rev. Stat. § 161.370(2). Usually, either the competency evaluator or another designated evaluator will offer an opinion as to whether the defendant needs to remain in the hospital, or whether treatment can occur in the community. Often, a person may be incompetent to proceed to trial, but can be safe in the community while receiving care.

A number of states have recently begun restoration programs within the jails themselves, avoiding transfers to a state hospital for restoration (figure 6.7). Providing restoration services in jail is controversial, with proponents emphasizing the immediacy of treatment available, and opponents noting the lack of therapeutic environment, among other problems. Of significant concern is the potential for prolonging incarceration of a person merely based on their mental disorder (Ash et al., 2019).

Jail Based Competency Treatment Program – San Diego County Sheriff’s Department

Figure 6.7 is a short video produced by the San Diego County sheriff’s department, introducing that county’s jail-based restoration program. Watch the video and consider the pros and cons of restoration services provided in jail versus in a hospital.

6.3.3 Alternatives to Restoration

As noted previously, restoration is only one of the options available to the parties where an accused person is not competent to proceed with their case. Other options (outright dismissal of charges or pursuit of a civil commitment, described in Chapter 9) would remove the case from the criminal courts more permanently, possibly to the detriment of victims, as well as the larger community. Victims deserve resolution in cases where they have been harmed, and important goals of the criminal justice system are not met if offenders are released into the community without accountability and supervision.

Outright dismissal of criminal charges may be a reasonable option in more minor cases, however. In the case of non-violent or lower-level charges, the lengthy process of evaluation, restoration, and resumption of court proceedings might take far longer than the person would ever have been jailed for an underlying charge of theft or trespass. Thus, insisting on continuing a lower-level case – with all of the delays involved – arguably places an unfair burden on people with mental disorders. In these cases, dismissal can be a just resolution, especially if support can be offered to avoid reoffense. Indeed, a systemic approach that anticipates justice-based dismissals of minor criminal charges in this category of cases might be a “diversion” opportunity like those discussed in Chapter 4. At what point in the Sequential Intercept Model would this type of decision and action occur?

6.3.4 Competency Determinations: Licenses and Attributions

“Competency Determinations” by Anne Nichol is licensed under CC BY 4.0.

Figure 6.4. “Competence to Stand Trial (CST) Flowchart” by D.A. Pinals & L. Callahan © Policy Research Associates is all rights reserved and included with permission.

Figure 6.5 Photo of group therapy by Mangionekd, CC BY-SA 4.0 <https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/4.0>, via Wikimedia Commons.

Figure 6.6. Photo of Oregon State Hospital Sign by Ocsdog, CC BY-SA 4.0 <https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/4.0>, via Wikimedia Commons.

Figure 6.7 Jail Based Competency Treatment Program – San Diego County Sheriff’s Department by the San Diego Sheriff’s Department is licensed under the Standard YouTube License.