6.5 Use of the Insanity Defense

The insanity defense is rarely presented in court, despite its intriguing nature that brings it into media coverage as well as dinner-table discussions. The defense is even more rarely successful in excusing a person from criminal conduct. Any concern that offenders can easily “get away with” criminal conduct via the insanity defense is not well-founded. In fact, people who criminally offend are overwhelmingly convicted of those crimes and punished – and this is true even when mental disorders are part of the picture. In the federal criminal system, for example, over 90% of charged defendants are convicted, almost all of them through guilty pleas without trial (Gramlich, 2019).

Only about one out of every hundred people being tried for felonies in U.S. courts assert the insanity defense, and the defense is successful only about 25% of the time. In other words, in about 75% of cases where the defense is presented (with all that entails – including professional evaluations), the defense is rejected and the person is convicted (Williams, 2020). Even in the unusual event of having conduct excused due to insanity, rarely does that person walk away free. Long hospital stays and periods of supervision are the norm for those “excused.”

As discussed earlier in this textbook, jails and prisons in the United States are filled with people experiencing mental illness and disability. While it is impossible to say how many were potentially eligible for an insanity defense, it seems reasonable to assume many were. Oregon (which is certainly not alone in its mental health numbers) reports, for example, that almost 30 percent of its adults in custody have serious mental disorders that need high levels of care. About 10% of Oregon adults in custody were rated to have “highest [mental health] treatment need” and another 18.4% were classified with “severe mental health problems” in 2022 (Oregon Department of Corrections, 2022). Where the issues were not raised at the time of conviction, it is impossible to know whether or how much of the conduct that landed these people in prison was a result of a mental disorder.

6.5.1 Prerequisites and Barriers to Defense of Insanity

The insanity defense is rarely successful because there are many barriers to its use, some that are inherent to the system, and others that are specific to certain defendants.

6.5.1.1 Proof of Insanity

The insanity defense is hard to prove. A successful insanity defense requires intricate proof on difficult issues of medicine and law, as discussed in this chapter. The insanity defense is generally an affirmative defense, meaning that it is a defense based on facts produced by the defendant, not by the state, which normally bears the burden of proof. Instead of the prosecutor having to prove that the person was “sane,” the accused person must offer proof that they were “insane” or not mentally capable of committing a crime, according to rules in their jurisdiction.

The proof presented by the defense must include an evaluation by a mental health professional, who will offer a diagnosis and explanation as to how a mental disorder impacted the conduct at issue. An evaluator would also consider whether the person is “faking” a mental disorder in order to gain some benefit, known as malingering. Remember that a diagnosis of a mental disorder is not the same thing as legal insanity. Many defendants who do have mental disorders, even significant ones, may be evaluated only to be advised that the evaluating expert does not believe that a mental disorder impacted their conduct sufficiently to warrant use of the defense.

Additionally, not every diagnosed and impactful mental disorder can, legally, form the basis for an insanity defense. Non-qualifying mental disorders are diagnoses that, while potentially very impactful, do not make a person eligible for the insanity defense; if criminal conduct arises from a non-qualifying disorder, it will not be excused. Non-qualifying mental disorders usually include personality disorders, substance use disorders, and conditions such as pedophilia, which are generally excluded from the insanity defense by statute. See Chapter 2 for more on these specific diagnoses.

Diagnoses that are permitted to form the basis for an insanity defense are known as qualifying mental disorders and commonly include psychotic disorders such as schizophrenia and mood disorders such as bipolar disorder. Other qualifying disorders include post-traumatic stress disorder or cognitive disorder resulting from traumatic brain injury. Developmental and intellectual disabilities can also form the basis for an insanity defense. Each of these disorders is discussed in detail in Chapter 2 of this text. In any case, the impact of a qualifying mental disorder must be so severe as to overcome a person’s ability to be criminally responsible for their behavior.

6.5.1.2 Defense Barriers

Another reason the insanity defense is not commonly used is that it is not necessarily the good “deal” some may imagine. Daniel M’Naghten, whose case inspired a tough new rule in his name, spent the rest of his life in a hospital and John Hinckley, who shot President Reagan in 1981 and inspired restrictive changes in the federal insanity defense, spent about thirty years in a state hospital and another decade on supervised release before being granted his freedom more than forty years later, in 2022. (Asokan, 2007; Johnson, 2021).

These cases are the rule, not the exception. A person who successfully asserts the insanity defense is almost certain to be committed to psychiatric care, often in a very restrictive setting such as a state hospital. And this commitment can be quite lengthy. Some states routinely commit patients to a state hospital for the maximum length of time they could be imprisoned if they had been found guilty (Oregon’s practice). Other states order commitment to care for an indeterminate period – with release nowhere in sight (McClelland, 2017). While early discharge is possible, it is not a certainty by any means. This result may not appeal to every person to whom the defense is available.

Defendants may also hesitate to assert the defense due to stigma around mental health in our society generally, or in their community specifically. Even if they do assert the defense, they may lack the prior diagnoses, history of treatment, and access to culturally competent assessments needed to gather the required proof. This is especially a problem for defendants who are Black, Indigenous, or People of Color (BIPOC). It has become ever more apparent that the deck is fully stacked against BIPOC defendants with mental disorders, who suffer disproportionately from lack of access to care, lack of appropriate providers, and rampant misdiagnoses that may make mounting a compelling insanity defense near-impossible (Perzichilli, 2020).

6.5.1.3 Prosecution Barriers

Even when a motivated, well-prepared and racially/financially/medically privileged defendant does pursue an insanity defense, the prosecution will, in our adversarial system, appropriately challenge the defense, perhaps with a competing evaluation or other evidence. Elected prosecutors, who are overwhelmingly white (95%) and male (73%) are also undoubtedly impacted by their own biases when deciding when and to what extent they will challenge an insanity defense (The Reflective Democracy Campaign, 2019). Even a progressive, elected prosecutor likely will have resistance to the insanity defense generally. A prosecutor’s job, after all, is to convict offenders and protect communities, and supporting the use of an excuse defense like insanity can seem at odds with those concerns.

Excusing guilt due to the presence of a mental disorder meets the demand of fairness in the criminal justice system — that is, not convicting a person of crime they did not intend to commit. However, it can also be very difficult and unsatisfying for victims. The insanity defense may be offered to excuse horrific and frightening offenses, including rapes or brutal murders. Victims may feel justice is not served where no sentence or punishment is imposed – and these valid feelings may persist strongly even while they appreciate the injustice of punishing a person excused under the defense. The observing (and voting) public is likely to align with victims in their attitudes towards the insanity defense, which tend to be heavily negative. The overwhelming public perception is that the insanity defense is overused (it is not) and there is a general belief that verdicts based upon it fail to keep the public safe, though there is little evidence to support that belief” (Hans, 1986).

6.5.1.4 Systemic Bias & the Insanity Defense

Doubtless, the racism, sexism and other improper biases inherent in all of our government systems, particularly in the criminal justice system, play a repeating role in the outcome of insanity defense cases. In some cases, statistics are available to illuminate this problem. For example, while juries and judges may be reluctant to excuse defendants who have done something harmful, studies suggest juries are more reluctant in the case of Black defendants. (Maeder). It is reasonable to conclude that similar bias exists amongst prosecutors, judges, and other decision makers in the criminal justice system. Bias likely impacts many mental health professionals conducting evaluations, defense attorneys who seek them, and every other cog in the wheel of the justice system. Because their behind-the-scenes work is less measurable than that of jury decisions, it is harder to produce supporting statistics as to some of these elements.

Regardless of the impact of each player, the end result is that the insanity defense is far more likely to succeed for white men. In Oregon, for example, of the approximately 600 people currently being supervised under Guilty Except for Insanity (GEI) verdicts, 82% are white, and 83% are male. Only about 6% are Black, another 6% are Latinx, and less than 3% are Native American (Psychiatric Security Review Board, 2021). This contrasts with Oregon’s jail and prison population which is about 9% Black and 14% Latinx (Vera Institute of Justice, 2019). The disparity in these numbers raises the question of why Black and Latinx defendants do not, apparently, assert or succeed in using the insanity defense at the same rate as white defendants. Though, as noted, the barriers to use of the defense are substantial for all, they appear to be more substantial for people of color.

6.5.2 SPOTLIGHT: John Hinkley, Jr. and the Insanity Defense

John Hinckley, Jr. was raised in a home not unlike that of many conservative American families. His father worked full time, and his mother stayed home to care for her son and keep up the house. Hinckley was emotionally dependent upon his mother throughout his adolescence, but none would ever have guessed that he would someday become notorious for an attempted presidential assassination.

The first signs of trouble came in the late 1970s when Hinckley first viewed the movie Taxi Driver. What began as a simple affinity for the film later became an all-consuming obsession. He adopted the dress, mannerisms, and lifestyle of the main character, and developed a burning desire for the actress, Jodie Foster, who depicted a teen prostitute in the film.

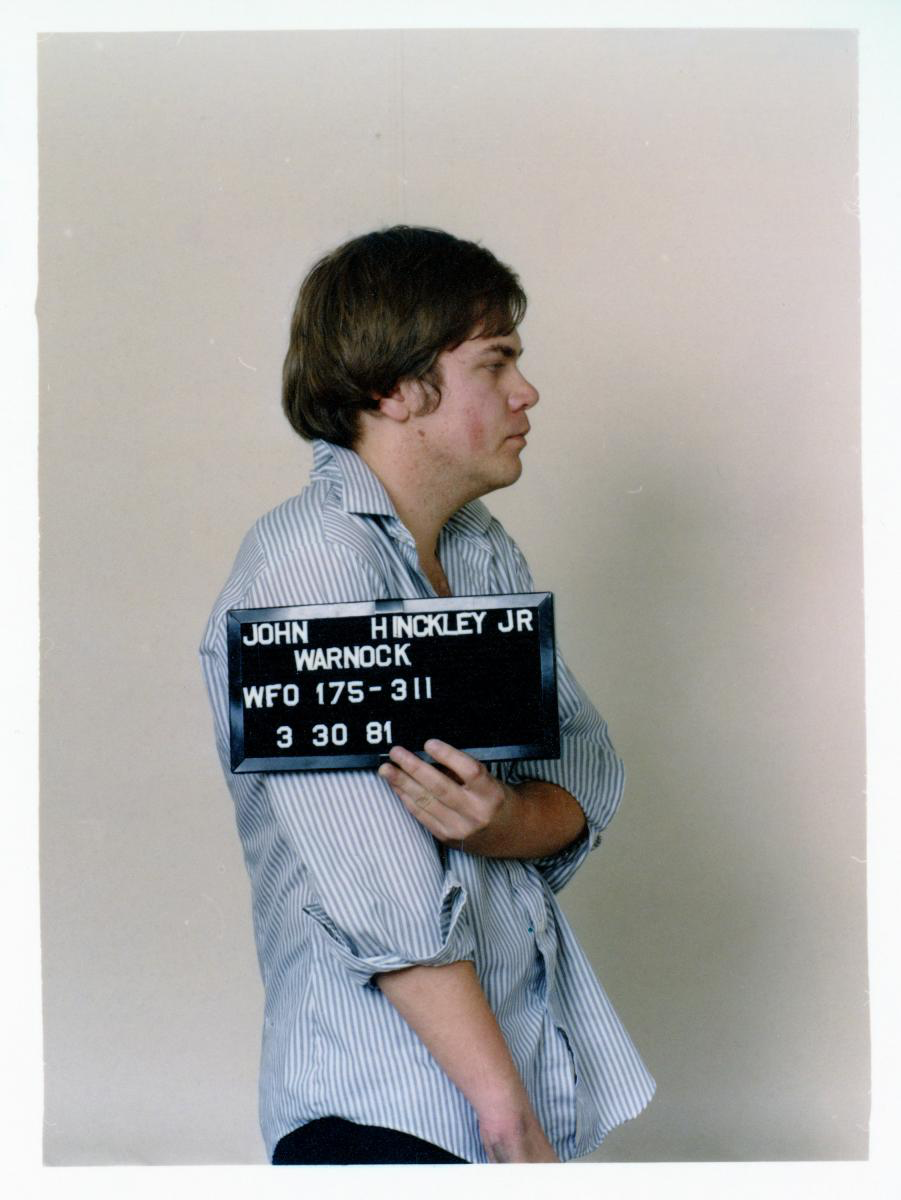

This obsession manifested itself outwardly in the form of stalking. As his mental health deteriorated, and Jodie Foster remained unimpressed by his attempts to get her attention, Hinckley came to the conclusion that he needed to assassinate the President of the United States. By the time he acted on this decision, Ronald Reagan was the sitting President. Hinckley made his attempt on March 29, 1981, and was promptly taken into custody (figure 6.10).

Figure 6.10. John Hinckley, Jr. is pictured here in 1981, after attempting to assassinate President Ronald Reagan. Hinkley injured four men, including White House press secretary James Brady, who much later died from his injuries.

John Hinckley was tried in federal court in 1982, and many Americans were outraged when he was found not guilty by reason of insanity. An ABC News poll conducted the day after the verdict was read indicated that 83% of respondents believed “justice was not done” and Hinckley should have been found guilty of a crime. This public pressure spurred Congress—and many individual states—to enact major reforms. In fact, eighty percent of the insanity reforms that happened over the next decade can be attributed to the outcry over the Hinckley verdict (Collins, Hinkebein, & Schorgl, 2022). All of the reforms focused on limiting a defendant’s ability to use the insanity defense in a criminal trial.

As for John Hickley, he was transferred to St. Elizabeth’s Hospital in Washington. He was released back into the community in July, 2016 after 41 years hospitalized under the supervision of mental health professionals.

6.5.3 Use of the Insanity Defense: Licenses and Attributions

“Use of the Insanity Defense” by Anne Nichol is licensed under CC BY 4.0.

“SPOTLIGHT: John Hinckley and the Insanity Defense” by Monica McKirdy is licensed under CC BY 4.0.

Figure 6.10. Photo of John Hinckley from https://www.reaganlibrary.gov/public/archives/photographs/jhjphotos/jhj-206.jpg is in the public domain.