7.2 Management of Mental Disorders in Custodial Settings

Mental disorders in jails and prisons have not been well managed over the decades. According to the National Alliance on Mental Illness (NAMI) , “there is a significant lack of access to adequate mental health care in incarcerated settings. About three in five people with a history of mental illness do not receive mental health treatment while incarcerated in state and federal prisons” (NAMI, n.d.). Someone diagnosed with a mental disorder may face challenges while in prison, including victimization from other incarcerated people, trouble following behaviors and rules imposed by correctional officers, and difficulty regulating symptoms in a strained environment. Oftentimes when someone’s behavior does not line up with what is expected in a prison or jail setting, the incarcerated person can face consequences like increased time in solitary confinement or less time spent accessing special programming. Someone with a mental disorder can decompensate (i.e., experience significant increase of symptoms) if their mental disorder is not properly treated in a controlled setting.

Prisons and other custodial environments face multiple barriers in providing treatment to people with mental disorders. For example, The Marshall Project, a non-profit newsroom that covers issues in the U.S. criminal justice system, has examined the lack of opportunities for people who are incarcerated to be evaluated for a mental disorder (Thomas & Elridge, 2018). Consequently, many incarcerated people’s mental health needs or disabilities remain unidentified. Significantly, many prisons are in rural areas, making it challenging to hire mental health professionals to treat incarcerated people. In addition, since the COVID-19 pandemic, many professions, including the behavioral health field, have experienced a mass exit of professionals from the field. This has increased the workforce shortage that ultimately impacts people needing experienced and educated professionals to treat their mental disorders. Burnout, which will be discussed more in Chapter 10 is another significant barrier when professionals are asked to do more work with fewer resources.

Jails and prisons house significantly greater proportions of individuals with mental disorders, including substance use and co-occurring disorders, than are found in the general public. While it is estimated that approximately 5 percent of people living in the community have a serious mental illness, comparable figures in state prisons and jails are 16 percent and 17 percent, respectively (Kessler et al., 1996; Ditton, 1999; Metzner, 1997; Steadman, Osher, Robbins, Case, & Samuels, 2009). The prevalence of substance use disorders is notably more disparate, with estimates of 8.5 percent in the general public (aged 18 or older) but 53 percent in state prisons and 68 percent in jails (Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, 2014; Mumola & Karberg, 2004; Karberg & James, 2005). Similarly, the co-occurrence of mental and substance use disorders is substantially higher among people who are incarcerated in prisons or jails (33 percent to 60 percent) compared with people who are not incarcerated (14 percent to 25 percent) (Wilson, Draine, Hadley, Metraux, & Evans, 2011; Baillargeon, et al., 2010; SAMHSA, 2012; SAMHSA, 2009).

7.2.1 SPOTLIGHT: Constitutional Right to Care in Custody

Given the enormous number of people with mental disorders who are confined in our nation’s jails and prisons, the ability of those people to access care and treatment is a significant issue. When an incarcerated person with a mental disorder is not provided with appropriate treatment for their disorder(s), that presents practical and moral issues, as well as legal ones. For example, how can a person with schizophrenia get better and succeed without necessary medications? If a person is confined and unable to independently seek care, doesn’t the government have an obligation to provide it? But, how much of an obligation, and how much care? Can a person refuse care? And can the government be liable for failure to provide care?

The questions are endless, and complex. However, this spotlight focuses on just three important federal court decisions that attempt to define, and limit, the rights of a person in custody to receive medical treatment, and to have a semblance of control over their treatment. Estelle v. Gamble (1976). In November of 1973, Gamble had sustained a serious back injury while working his prison job. He complained of excruciating pain over the next 3 months. While he was seen by several medical personnel, his injury was not taken as seriously as it would have had he not been incarcerated. When he was erroneously cleared to go back to work, but was in too much pain to do so, he was then punished. Eventually, Gamble sued, citing his Eighth Amendment rights. The Eighth Amendment of the U.S. Constitution prohibits cruel and unusual punishment. While the writers of the Constitution originally intended this to mean torture, or other physical inflictions of pain, the United States Supreme Court has since had to decide what other actions—or inactions—may also constitute cruel and unusual punishments. In 1976, while examining Gamble’s case, it was decided that “deliberate” failure to provide adequate medical care to inmates may indeed constitute cruel and unusual punishment. While the result in Estelle v. Gamble seems positive for prisoners seeking care, the “deliberate indifference” standard established in that case has proven nearly impossible for plaintiffs to prove. In order to hold a prison liable when they do not provide needed care, a plantiff must sue in court and prove that the prison was aware of the need for care and consciously chose not to provide it.

Bowring v. Godwin (4th Cir., 1977). Larry Bowring, convicted of robbery, attempted robbery, and kidnapping, was incarcerated in the Virginia State Prison System. In preparation for an upcoming parole board hearing, Bowring was given a psychological examination. That examination concluded that Bowring would likely not be able to successfully complete the parole period due to the psychological deficits observed in the examination. This finding was one of three reasons Bowring was denied parole. Bowring felt that he ought to be given psychiatric treatment to help him prepare for the next parole hearing in hopes that he would be granted parole, yet the prison system did not make any attempts to either diagnose or treat him. Citing his constitutional rights, Bowring sued. Bowring asserted that denying him a diagnosis and treatment, despite knowing there was a need, constituted not only cruel and unusual punishment in violation of his Eighth Amendment rights, but also a denial of due process of law in violation of his Fourteenth Amendment rights. Ultimately, the Fourth Circuit federal court held that all inmates are entitled to psychiatric treatment, with limitations. For example, the court held that prisons should not be held accountable for providing treatment if it would be too costly or take too much time to complete. Though not a Supreme Court case, the Bowring opinion is often cited for the idea that psychiatric care is no different than other medical care, and certain denials of this care may violate the Constitution.

Washington v. Harper (1990). Walter Harper had been incarcerated in the Washington prison system since 1976. He had been diagnosed with psychiatric problems and prescribed antipsychotic medications, but Harper didn’t want to take them. While he was not taking his medication, he often became violent and posed a danger to himself and others. Twice, he was transferred to the Special Offender Center (SOC), which was a psychiatric facility for prisoners. While there, Harper was forced to take his antipsychotic medications involuntarily. Typically, when inmates at the SOC did not want to take their medications, there had to be a formal hearing to decide whether or not it was legally permissible. During Walter’s second stint at the SOC, in 1983, the Center did not provide this judicial hearing. Harper sued. Ultimately, in 1987, the United States Supreme Court ruled in Washington v. Harper that inmates with serious mental disorders can be administered antipsychotic medications against their will, but only if the state can prove that they are dangerous to themselves or others, and that the medication is in the best medical interests of the prisoner. In other words, under Washington, a prisoner has a limited right to refuse medications.

7.2.2 Evaluation, Assessment, and Screening

A screening is a standardized instrument that is designed to flag incarcerated individuals who are at risk for a targeted problem, such as a mental or substance use disorder. These tools do not provide diagnostic information nor do they provide guidance on the severity of any disorder. In comparison to a screening, an assessment instrument provides a more in-depth examination of the nature and severity of a targeted problem. The results of assessment instruments, typically administered by behavioral health professionals, can assist in the development of individualized treatment plans.

Many state prison systems have a screening and assessment custody setting an incarcerated person enters through first prior to being placed in the prison they will serve the majority of their term of imprisonment. In the Oregon Department of Corrections, for example, when a person begins their custodial sentence, they first go to Coffee Creek Correctional Facility to complete their screening and intake. A person may be ‘flagged’ for likely needing mental health support if they have been involved with the Psychiatric Security Review Board (PSRB), accessed mental health services in the community prior to incarceration, are under the age of 25 years-old, or have a history or current ideation of self-harming behaviors. During this screening process, a person is also screened for developmental disabilities, where psychological testing may be completed to assess their level of functioning. An incarcerated person generally spends three weeks in the assessment and screening phase before they are placed in appropriate housing based on their current needs. The Oregon Department of Corrections and the Bureau of Prisons rate incarcerated people based on their mental health severity and their ability to tend to their activities of daily living (ADLs). Examples of ADLs include getting out of bed, dressing oneself, eating, hydrating, bathing, and using the toilet. The level of a person’s mental health needs and their ability to attend to ADLs will impact that person’s housing assignment.

In 2017, the Bureau of Prisons released a report on the use of restrictive housing for incarcerated people with mental disorders. Findings revealed that the BOP cannot accurately determine the number of incarcerated people who have a mental disorder because staff do not always document mental disorders. According to this report, because mental disorders are not always documented, the BOP cannot ensure they are providing appropriate care to incarcerated individuals (Office of the Inspector General, 2017). Sadly, this indicates that incarcerated people are not being identified as needing treatment, so they are not receiving treatment. This current process continues to perpetuate a system that does not set a person up for success once they are released from custody. Lastly, this also indicates that the rate of mental disorders in custody are higher than reported, if not all incarcerated people are routinely and thoroughly assessed for mental disorders.

7.2.3 Housing in Custody

Housing in correctional settings can vary depending on the security level of the facility. A maximum security prison will have more strict and isolating housing settings than a medium or minimum security correctional facility. Housing classification is a way to separate incarcerated people and keep a correctional facility safe for both staff and incarcerated people. It is a challenge for proper housing classification that symptoms of a person’s mental disorder may be triggered easily in some of the few housing options that are available in correctional settings.

Figure 7.2a. The main entrance of United States Penitentiary Leavenworth in Kansas. It was the largest maximum-security prison in the United States until 2005.

Figure 7.2b. Another view of Leavenworth, which is now a high-medium security prison.

The housing classification of the incarcerated person determines their access to certain programming and privileges within a facility. For instance, an incarcerated person in a minimum to low risk facility will likely have access to a milieu, also known as a controlled social environment within a prison or jail. Within prison milieus are often therapeutic communities, which provide structure, responsibility, and life skills to emulate and develop skills necessary once the person is released from a controlled environment. Keeping this in mind, it will be helpful to understand the different types of housing settings in correctional settings.

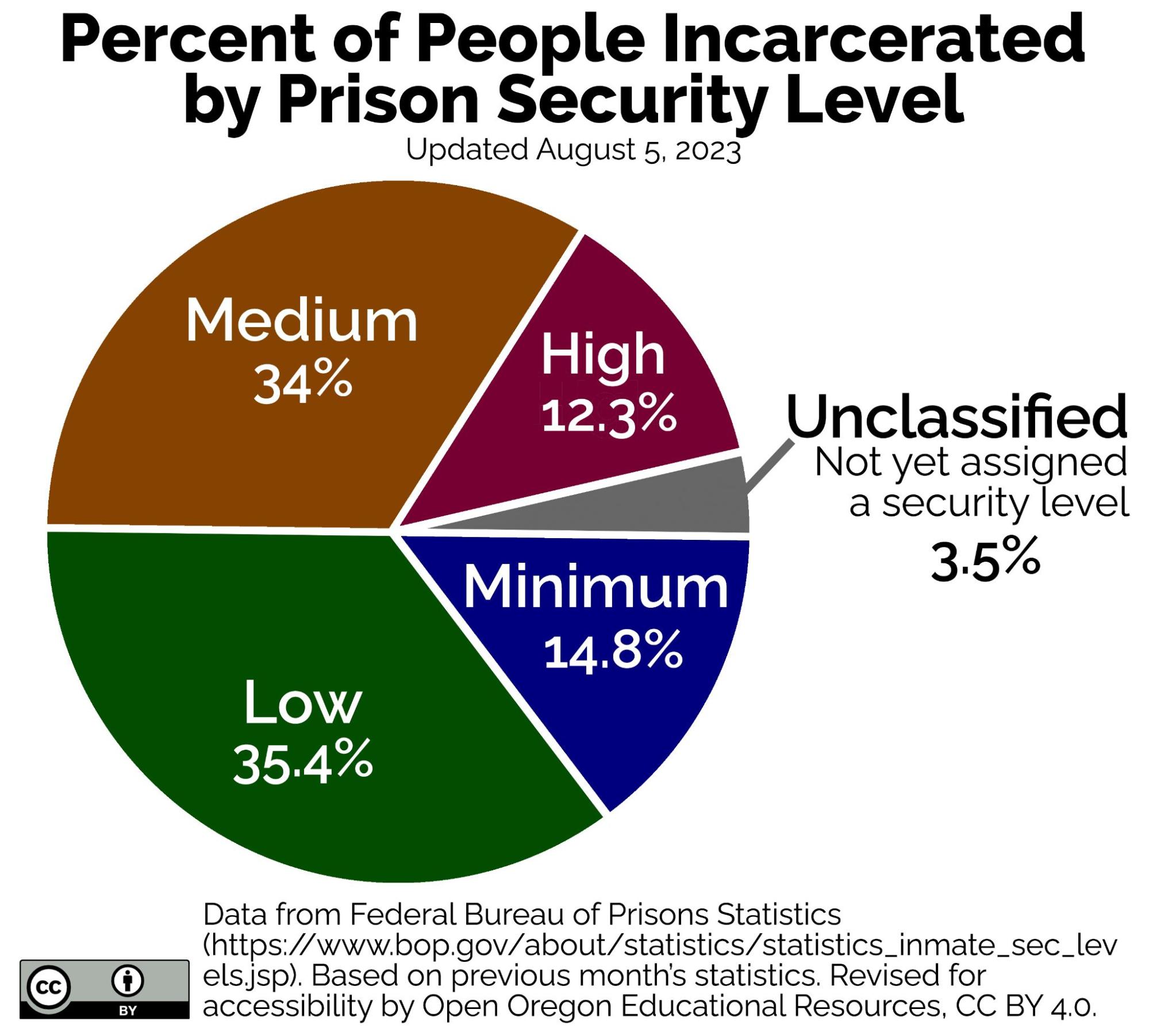

|

Security Level |

Number of Inmates |

Percent of Inmates |

|---|---|---|

|

Minimum |

23,306 |

14.8% |

|

Low |

55,831 |

35.4% |

|

Medium |

53,570 |

34.0% |

|

High |

19,451 |

12.3% |

|

Unclassified |

5,558 |

3.5% |

Figure 7.3. Here is a breakdown of the security levels in the federal Bureau of Prisons. This is a pie graph showing the number of incarcerated people in each security level from national level in the United States (Bureau of Prisons, 2023).

7.2.3.1 Dorm Settings

Dorm settings are generally found in minimum or medium security correctional facilities. Dorm settings have rows of bunk beds where incarcerated people sleep in one large room. These setups are also generally used when overcrowding is an issue. Some pieces to consider, does this foster a good environment for someone who is struggling with a mental disorder? If someone experiences schizophrenia, anxiety, or autism, this environment can be overstimulating. Privacy is another piece to consider. Although someone is given the ‘liberties’ to not be housed in a jail cell for the majority of the day, a significant piece of their privacy has been stripped away from them when living in a dorm setting.

7.2.3.2 Cells

Cells are settings where incarcerated people share a small room with a toilet and sink. Cells often house two to four people who sleep in bunk beds. Cells are generally what get portrayed in the media (Zokukis, 2021). While privacy and autonomy are more obtainable in a cell setting, consider limitations that are present as well. For example, potential areas for victimization may occur in this type of setting, especially for someone who has a mental disorder.

7.2.3.3 Solitary Confinement

Solitary confinement is usually defined as a single cell where the incarcerated person resides. Solitary confinement receives a lot of attention because it can have detrimental effects on human beings spending such a great amount of time in isolation. Generally, someone is housed in solitary confinement when there are behavioral issues that correctional staff are ill-equipped to manage. As you can imagine, people with mental disorders can easily be placed in solitary confinement if staff are not properly trained to recognize and manage the needs of this group.

In 2015, President Obama requested a review of “the overuse of solitary confinement” across American prisons. There are situations in prisons where incarcerated people need to be housed separately to maintain safety of other incarcerated people and staff. This presidential requested review encouraged prison systems to develop strategies to reduce use of solitary confinement. Recommendations for the Bureau of Prisons (BOP) included diverting incarcerated people with serious mental illness to mental health treatment programs and increasing the capacity of existing secure mental health units (United States Department of Justice Archives, 2017).

7.2.3.4 Oregon Department of Corrections Housing Units

The Oregon Department of Corrections (DOC) has specialized housing units for people with mental disorders. The main goal for housing people with mental disorders in correctional facilities is to house them in the least restrictive environment possible. Incarcerated people who have more significant mental health needs are housed in single cells and have access to a comprehensive clinical team with on-going mental health support. These people are isolated from the general population in an attempt to keep them as safe as possible. Less restrictive mental health housing units permit incarcerated people to leave their cells, go outside, and interact with other peers. These opportunities allow for people with mental disorders to begin to learn and practice social skills while still in a controlled environment. Lastly, Oregon DOC has mental health units that specifically house people with mental disorders. They are separated from the general population to decrease the chances of them being exploited. These units provide peer mentorship and skills training to teach safety, avoid conflicts, and gain social skills.

7.2.3.5 Bureau of Prisons Restrictive Housing Units

The federal Bureau of Prisons (BOP) utilizes three types of restrictive housing units (RHUs) to house incarcerated people, to include people with mental disorders. The purpose of these RHUs is to maintain the safety of the correctional facility. Policies are in place to ensure correctional staff regularly evaluate the appropriateness of an incarcerated person remaining in RHUs, however there is no limit on how long an incarcerated person can be housed in a RHU (U.S. Department of Justice, 2017).

7.2.3.6 Bureau of Prisons Special Housing Unit

Special housing units (SHU) are utilized for disciplinary segregation in the federal prison system. The SHU is generally solitary confinement and restricted from the general population (U.S. Department of Justice, 2016). In a 2017 report, “the BOP states that the SHU policy does not specifically address conditions of confinement for inmates with mental illness (Office of the Inspector General, 2017).” Policy has been created to place boundaries around who can be in the SHU before receiving a review from staff. This policy also requires that after 30 days of continuous placement in SHU, the incarcerated person will receive a mental health evaluation (U.S. Department of Justice, 2017).

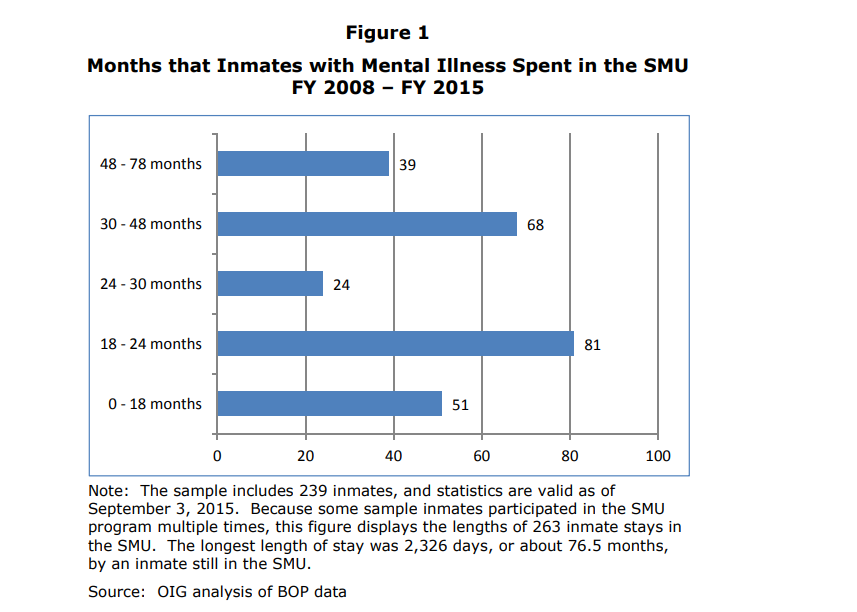

7.2.3.7 Bureau of Prisons Special Management Units

Special Management Units (SMU) are utilized in the BOP when an incarcerated person’s behavior poses a greater risk to the safety of the correctional facility. The BOP’s policy excludes placing people with severe and persistent mental disorders in these units unless there are extenuating circumstances. SMU units are more restrictive than the general population of correctional facilities but become less restrictive as an incarcerated person demonstrates progress and improvement in the SMU. Incarcerated people in SMU are evaluated by mental health staff every 30 days and emergency mental health care must always be accessible (Office of the Inspector General, 2017). According to a report written by the Office of the Inspector General, it was found that incarcerated people with mental disorders spent almost 14 months longer in SMUs when compared to all incarcerated people (U.S. Department of Justice, 2017).

7.2.3.8 Administrative Maximum Security Facility (ADX)

Administrative Maximum Security Facilities house violent and escape prone incarcerated people who are not safe to be housed with the general population (U.S. Department of Justice, 2017). The BOP’s mental health policy also excludes incarcerated people with severe and persistent mental disorders from ADX placement unless there are extraordinary security concerns that cannot be met elsewhere. Incarcerated people with severe and persistent mental disorders who remain in the ADX must have an individualized mental health treatment plan and be provided with at least 10, and as many as 20, hours of out-of-cell time per week, consistent with their treatment plan. In July 2015, the ADX issued local policy stating that all incarcerated people will receive psychotropic medications when clinically determined. It also states that incarcerated people identified as having a mental disorder, be seen by a Psychiatrist, Physician, or Psychiatric Nurse every 90 days, or more often if clinically indicated. Qualified health practitioners are required to visit each incarcerated person in this housing unit daily. After every 30 calendar days of continuous placement in a restrictive housing unit, each incarcerated person must be examined by mental health staff to evaluate any threat to harm to themselves or others. This is important to note that not only are these units housing people with severe and persistent mental disorders, they are also very limited on the allocated time out of their cells. Incarcerated people in these housing units are out of their 80 square foot (minimum) cell up to 20 hours per week.

Figure 7.4. The horizontal axis shows the number of incarcerated people, and the vertical axis shows months spent in the SMU.

This bar chart shows the months that incarcerated people with mental illness spent in the Special Management Unit (SMU) between 2008 and 2015. The sample includes 239 incarcerated people, and statistics are valid as of September 3, 2015. Because some sample inmates participated in the SMU program multiple times, this figure displays the lengths of 263 inmate stays in the SMU. The longest length of stay was 2,326 days, or about 75.6 months, by an incarcerated person still in the SMU. Source: OIG analysis of BOP data.

|

Time Spent in the SMU |

Number of Inmates |

|---|---|

|

48 – 78 months |

39 |

|

30 – 48 months |

68 |

|

24 – 30 months |

24 |

|

18 – 24 months |

81 |

|

0 – 18 months |

51 |

The table above simply reads the data explained in the bar chart. This table references the same information, however in an alternative viewing format.

7.2.4 Victimization in Custody

Victimization of incarcerated people is highly monitored considering they are among a protected class while in a custody environment. Oversight of correctional facilities is in place to avoid incarcerated people from victimizing one another, to avoid correctional staff from harming incarcerated people, and to avoid incarcerated people from harming themselves.

7.2.4.1 Prison Rape Elimination Act (PREA)

The Prison Rape Elimination Act (PREA) was passed by Congress in 2003. The purpose of this act is to prevent incarcerated people from being raped in correctional settings. PREA is particularly important for people with mental disorders who may be especially vulnerable to victimization in custody. On-going training is required for all staff working in a correctional setting. This act also ensures that incarcerated victims of sexual abuse have the right to treatment regardless of whether they are willing to cooperate in an investigation. Professionals working in correctional settings are required to report any allegations of sexual abuse, sexual harassment, and any third-party and annonymous reports to investigators. Correctional institutions must undergo audits to ensure they are in compliance with PREA (National PREA Resource Center, n.d.).

7.2.4.2 Suicide Prevention

The Bureau of Prisons (BOP) requires that all staff members receive annual training minimally on suicide prevention. Psychology staff provide crisis intervention and mental health support services as needed in the correctional facilities, which generally include individual therapy and some group therapy. Although, suicide rates are lower nationally in controlled settings than in the community, it is a topic that much continuously be acknowledged to prevent any completed suicides from occuring in a controlled environment (Federal Bureau of Prisons, n.d.).

7.2.4.3 Power Differentials in Controlled Settings

A power differential is unavoidable in a controlled environment and especially unavoidable between any staff member with decision-making authority and an incarcerated person. For instance, a psychologist has clinical recommendations for an incarcerated person. A correctional officer has decision making authority on which housing unit an incarcerated person is placed in a correctional facility. These dynamics are important to recognize because they have the power to greatly impact someone’s life. Power differentials are unavoidable, so staff must be aware of how these decisions have an impact and contribute to the therapeutic relationship or relationship between correctional officer and incarcerated person.

Staff should take notice of these impacts and find ways to reduce potential harm. For instance, a therapist working in a jail or prison holds the keys to leave the facility at the end of their shift, it may be advantageous to keep their keys out of eye sight during a counseling session. Another consideration is being mindful of boundaries between staff and incarcerated people. For instance, correctional officers must maintain strong, professional boundaries at all times with incarcerated people. Correctional officers hold power in a correctional facility and having ‘loose’ boundaries can be confusing and ultimately harmful to the incarcerated person. If a correctional officer vacillates on their boundaries (i.e. changing rules, being more friendly one day and more punitive the next) it can be conflicting information for the incarcerated person. It is important to remain consistent and transparent with communication. A final example may be a corrections counselor asking in casual conversation about someone’s upcoming court case and then later using that information in a clinical recommendation. A good reminder is to ask yourself, “am I asking this question because it is needed to do my job, or am I asking this question because I’m curious?” If asking because you are curious, there is likely more room to cause harm towards the incarcerated person.

7.2.5 Management of Mental Disorders in Custodial Settings Licenses and Attributions

SPOTLIGHT: Constitutional Right to Care in Custody, by Monica McKirdy, is licensed under CC BY 4.0.

Open Content

Figure 7.2a. “Leavenworth Main Entrance” by Cruise-Pics.com is licensed under CC BY-NC-ND 2.0.

Figure 7.2b. “No-Person’s Land” by Cruise-Pics.com is licensed under CC BY-NC-ND 2.0.

Figure 7.3: “Percent of People Incarcerated by Prison Security Level” is adapted from “BOP Statistics: Prison Security Levels” by Federal Bureau of Prisons, which is in the Public Domain. Modifications by Michaela Willi Hooper, licensed under CC BY 4.0, include increasing contrast, retitling, and adding labels for accessibility.

Some information referenced from:

Report and Recommendations Concerning the Use of Restrictive Housing (justice.gov)

Photos of BOP: CC BY-NC-ND 4.0

Office of the Inspector General (2017) https://oig.justice.gov/reports/2017/e1705.pdf

Copied verbatim from page 18 of this report: “SMU Conditions of Confinement” is from “U.S. Department of Justice Report and Recommendations Concerning the Use of Restrictive Housing by Office of the Inspector General” and is in the public domain.