Y2 Unit 3.4: Open Educational Practices as Assessment

As we discussed in Year 2, Unit 1, Pilot Instructors have the opportunity to engage your students in deep learning, and simultaneously improve the pilot textbook for future learners, with Open Educational Practices. Using Open Educational Practices, you and your students can create openly licensed content to be shared in the launch version of the textbook. Remember, it is not a project requirement to include student contributions in your course materials.

Author team members have let the Project Manager know if there are spaces for student work designed into the current textbook manuscript draft. Pilot Instructors (whether or not they are also authors) can design assignments that generate student work to fill these gaps. Our textbook authors also had the option of using Open Educational Practices when they drafted their textbook manuscripts. To read or review how we approached this topic with our textbook authors, visit Year 1, Unit 3.

Student Agency

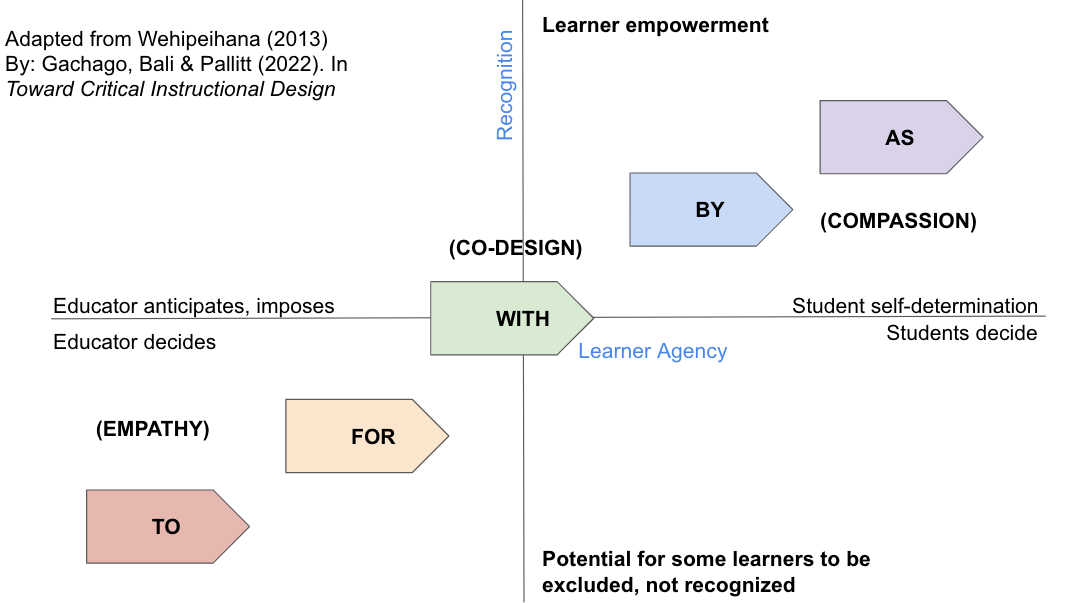

Open Educational Practices are teaching methods that prioritize student agency when creating new knowledge. They include the approaches, supports, and processes that scaffold student tasks and choices. As figure Y2 3.5, below, shows, the goal of Open Educational Practices is for students to design key parts of their course work by and as themselves.

In traditional educational settings, instructors design to or for students. This means that instructors offer one learning solution they believe will help students learn best. This comes from a place of care but assumes the instructor’s expertise and limits student input. The instructor may not be fully aware which student needs are a priority. Students have limited opportunities to name their needs to the instructor and one another.

In higher education, designing with students is often the best instructors can do. The instructor manages institutionally-imposed restrictions, but discusses student needs and comes up with a range of solutions together. At this level of student participation, learners name diverse needs, priorities, and solutions not previously known to the instructor. Students suggest strategies for addressing needs that are not necessarily within the instructor’s existing array of possible solutions.

The highest levels of participation allow students to design their learning by and as themselves. When students design learning by themselves, they discuss their needs and suggest a range of solutions. However, they still need approval from the educator for a grade. When students design as themselves, they do not need to justify their worldview, approach, or choices. This is learner self-determination. This could occur within an educational institution in some extracurricular experiences or in community engagement projects, or outside of formal education altogether.

Open educational practices move beyond what David Wiley calls “disposable assignments,” or assignments that have no utility outside the limited duration of a course (Wiley, 2013). Importantly, Jasmine Roberts-Crews argues that “Black feminist influences are present in the notion that there are transactional assignments that lead to less critical consciousness and more communal assignments that involve co-creation and iterative practices” (Roberts-Crews 2023). In the terms of the diagram in figure Y2 3.5, disposable or transactional assignments are typically designed to and for students. In contrast, however, students can create renewable assignments by designing assignments with you or by and as themselves. They can create their own prompts, rubrics, and projects to fulfill their learning goals.

Choose Your Challenge

Open Educational Practices evoke complex feelings. Alongside excitement and newfound relevance in their coursework, “students might experience emotional pain, feelings of inadequacy, and vulnerability” (Pearce et al). As you consider open pedagogy opportunities, consider the degree of challenge you want to accept according to your own workload and teaching experiences.

If you are new to teaching or if you are managing big changes in your teaching life such as switching to a different institution, you might consider practices at a lower challenge level. These may include introducing students to Creative Commons licensing, allowing students to design their own class project, or creating shared glossaries and slides to share with future students. You might ask your students to create a zine or submit a letter to the editor of a local paper. In contrast, if you are an experienced educator ready to tackle projects that require more scaffolding, consider ideas at a higher challenge level. These opportunities include asking students to write textbook chapters or examples to fill in gaps in content, to create video introductions to chapter content to share with the textbook, or to identify an open journal for possible publication of their coursework. Our textbook authors can also advise on opportunities for pilot coursework to contribute to the textbook project.

Designing for Informed Consent

Open educational practices are rooted in respect for student agency and authority. The Open Pedagogy Student Toolkit [Website] helps students understand the benefits, and the rights and responsibilities, that come with being a student creator. Open Licenses for Students [Google Folder] includes helpful slide decks orienting students to copyright and open licenses. You might also consider inviting a librarian to class for a visit or asking them to prepare an introductory video to explain how licensing works in support of student agency.

Discussing the rights and permissions of open licenses can serve multiple existing course goals relating to research methods, academic integrity, scholarly communication and collaboration, and public service. In your course planning, consider how and when you talk with students about academic integrity and their rights as content creators. For example, do you already facilitate critical discussions about how knowledge is produced and shared? Do your course goals already address issues of creative expression, analysis or evaluation of authority and power, data privacy, or education and social justice?

To ease into open pedagogy, consider trying one small strategy in your pilot. For example, biology instructor Michelle Huss incorporates student-generated exam questions as assessment. Michelle coaches students on creating and sharing their work using instructor videos, handouts, and transparent assignment design [Google Doc]. In these ways, Michelle sparks critical thinking about the rationale behind her methods. For Michelle, folding in discussion of expression and power is part of the assessment process itself.

Open Educational Practices are rooted in respect for student agency and authority. However, students are often unused to seeing themselves as agents and authors. They may experience any or all of the following barriers.

Figure Y2 3.7 To what extent do our suggested solutions lower the potential barrier? How would you address each one? Barrier Possible Solution Anxiety about being graded on their willingness to share their course work Consistent messaging that willingness to share with an open license does not impact student grades Perceived additional workload from participating in an open pedagogy project Clear grading rationale explaining that students will not be penalized with additional work for participation Feeling inadequate or uninformed about knowledge creation that is “good enough” to share Normalizing being new or being a learner, emphasizing the gaps in “expert” knowledge, and offering alternatives to public sharing Inattention or absence from informed consent discussion Document each student’s review of informed consent content with a quiz or short assignment

To start a conversation with students about informed consent for open licensing, you might use one of the following strategies.

Strategy 1: Create a discussion forum on open licenses

Create a Discussion Forum for students with the following questions and ask them to comment on one other person’s posts:

- Do you notice anything different about courses that use openly licensed textbooks? Hint: we’re using one in this class!

- How would you explain what an open license is to a friend or family member? Review the short video What is Creative Commons [Streaming Video] and then define it in your own words.

- Why might a student want to attach an open license to their course work? Why might a student decide not to share their work with an open license?

- Search for a topic on YouTube and filter for Creative Commons (Watch How To Find & Use Creative Commons Videos On YouTube Without Copyright Claims [Streaming Video] for help with this process). Can you find an example of openly licensed student-created work?

Strategy 2: Review existing openly licensed student projects as a class

Share open pedagogy projects that Oregon students have developed, for example, Elizabeth Pearce’s Contemporary Families textbook [Website] or Michelle Huss’s Open Pedagogy Human Genetics Pre-Allied Health [Google Doc]. Ask students to review each project and answer the following questions:

- What do you know about the students who created this work? Did they choose to include biographical information or not?

- Who is the intended audience for this work? How do you know?

- What permissions come with this work? Review About CC Licenses [Website] to understand what future users can and can’t do.

Strategy 3: Students teaching students

Ask students to create an openly licensed one-page guide to a student-selected topic related to course learning outcomes, either in small groups or as a class over two class sessions:

- In the first session, model for students how to search for openly licensed images in the repositories recommended by Open Oregon Educational Resources [Website]. Show students how to provide attribution for open content using the Attribution Style Guide [Website].

- In the second class session, give students work time together on the guide, and then model how to write open licenses statements together. Ask which students would like to receive attribution, or if they’d prefer attribution as a group, and which open license they want to attach. Uploading each guide to a page in your learning management system will allow students to revisit the work they did together.

Additional resources

Keep in mind that we will be widely sharing your open curriculum a year or two from now. That’s a long time from a student perspective, especially if some of your class graduates or transfers between now and then. We recommend that you collect personal email addresses so that we can follow up later if we need to gather bios and headshots, or clarify what kind of credit student contributors want (e.g. no credit, anonymous, pseudonym, your name?).

The following tools help instructors to document student informed consent for open licensing:

- Student Agreement to Publish Course Work under a Creative Commons License [Google Doc] from Kwantlen Polytechnic University invites students to initial their preferred open license from a list. This form is great if you are collecting student work to post yourself as a playlist on YouTube or in your institutional repository.

- Google Forms are a great way for students to indicate consent as well as their preferred permissions for sharing. Student Consent: Sharing with Class Resource [Google Form] can be modified to suit your class.

- Student Release of Course Materials for Public Availability [Google Doc] allows students to document permission for an institution or instructor to reproduce and distribute work on a royalty-free basis for educational purposes and public communication.

Unit Self-Check Questions

Licenses and Attributions for Open Educational Practices as Assessment

Open content, original

“Open Educational Practices as Assessment” by Veronica Vold for Open Oregon Educational Resources is licensed under CC BY 4.0.

Open content, shared previously

Figure Y2 3.5. Learner Agency Model by Maha Bali, Daneila Gachago, and Nicola Pallitt is adapted from Nan Wehipeihana’s 2013 Model and is licensed under CC BY-NC 4.0.

Figure Y2 3.6. “Open Pedagogy & Student Discomfort: Visual Model Blank Template” by Liz Pearce, Silvia Lin Hanick, Amy R. Hofer, Lori Townsend, & Michaela Willi Hooper is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.

References

Pearce, Liz, Silvia Lin Hanick, Amy Hofer, Lori Townsend, and Michaela Willi Hooper. “Your Discomfort Is Valid: Big Feelings and Open Pedagogy.” October 21 2022. https://openoregon.org/your-discomfort-is-valid-big-feelings-and-open-pedagogy/

Roberts-Crews, J. (2023). The Black Feminist Pedagogical Origins of Open Education. Journal of Interactive Technology and Pedagogy, 23. https://cuny.manifoldapp.org/read/the-black-feminist-pedagogical-origins-of-open-education/section/f46578ee-e6b4-4d4d-b356-dda3f3cd1806

Wiley, D. (2013). What is Open Pedagogy? https://opencontent.org/blog/archives/2975