Y2 Unit 9.3: Attributions and Citation Lists Through an Equity Lens

In Year 1, Unit 2 we covered the difference between citations and attributions. In short, citations have an academic purpose because they tell your reader where ideas that you quote, paraphrase, or summarize, came from. Attributions have a legal purpose because writing an attribution statement is a legal requirement of reusing openly licensed works. What citations and attributions have in common is that they communicate which sources that you relied on to create your work.

Here we’ll go deeper to consider who receives credit in our attribution and citation lists.

Critical Analysis of Copyright and Permissions

Copyright is a legal framework within imperfect and evolving social and political institutions. Thinking about rights and permissions can consume a great deal of energy for open textbook creators, as you have no doubt noticed. While copyright compliance is important, an equity framework might also ask:

- Are there any contributors who have been left out, not acknowledged, or not compensated?

- What can we do to correct power imbalances that have enabled some people to take credit for other people’s work, traditions, and creativity?

- How do we acknowledge all contributors clearly, concisely, and consistently?

Creative Commons licenses are a useful way for copyright holders to be clear about the permissions they give to future users of their work. But people using openly licensed materials to work “in the open” can remain aware of – and critical of – the dominant worldview that they are operating in. As an example, open educator Maha Bali unpacks her thoughts about the concept of “permission” in the essay Openness in Whose Interest? [Website]:

For me, the violation of copyright in Egypt is transgressive. People won’t be able to learn medicine (because the dominant knowledge of medicine is in English by Western textbooks and scientists, in expensive imported textbooks) so they copy illegally. It’s against the law. But it’s an unjust law.

Then someone gives permission. But the entire discipline and industry have been gatekeeping and withholding for so long. They choose what to share and what to keep. They still control the permission. It seems paternalistic and neocolonial in this sense. Because again it reproduces a cycle of MORE Western knowledge offered to the world (how generous) and in comparison less minority knowledge, because also, minorities have less funding and resources to be open, less time to be open, more to lose and less to gain by being open.

If we want to tackle openness from a social justice perspective, we need to always ask whose interests are served by what we do and say (Bali, 2019).

For more critical analysis of copyright, we recommend optionally reading an earlier version of this curriculum written by Michaela Willi Hooper, who participated as a Research Consultant, and Marco Seiferle-Valencia, who participated as an OER Development Consultant. Their coauthored unit, Building OER Together for All: Attributions, Access, and Authorship [Website], takes a deep dive into topics such as the connection between copyright law and colonialism, and how copyright law created the need for open licensing in the first place.

Citation Justice and Diversity

The Position Statement on Citation Justice in Rhetoric, Composition, and Writing Studies [Website] makes the valuable argument that citation is “…a decision to amplify some voices over others, and an argument about whose voices and perspectives are valid, credible, and worth drawing from as we build knowledge in the discipline” (Sano-Franchini et al., 2022). Citation practices define the scope of a discipline and determine scholars’ ability to demonstrate their impact in order to apply for tenure or promotion.

In many disciplines, people with minoritized identities were historically barred from attending or working within universities and therefore were prevented from creating and engaging with scholarship. Even as many groups gained legally protected access to academia, their scholarship was and still is unethically appropriated by those with more privileged identities. Approaching scholarly conversations with integrity is a practice of accountability and justice.

Movements like #CiteBlackWomen [Website] and #DignidadLiteraria [Website] exist to counteract historical and ongoing inequities and the lack of representation of people with minoritized identities in academic discourse, academic publishing, and the scholarly conversation.

Along these lines, the Cite Black Women campaign recommends five practices:

- Read Black women’s work.

- Integrate Black women into the CORE of your syllabus (in life and in the classroom).

- Acknowledge Black women’s intellectual production.

- Make space for Black women to speak.

- Give Black women the space and time to breathe. (Smith et al., 2021)

For this last pass through your chapters, please check that you cite authors from underrepresented backgrounds. Take the time to look into credible resources and writing from activists and advocates. Work with subject matter experts and community representatives from diverse backgrounds to ensure that the content is accurate, relevant, inclusive, and free of bias and stereotypes; this includes images and visual representation.

Make sure that your sources are current (where applicable). Be sure to read the work you are citing to see if it aligns with an equity lens. Perhaps there is a more recent source whose perspective and approach will be a better fit.

If you need ideas about where to search for more diverse sources, we recommend the guide from the University Libraries at the University of Maryland [Website]. It is full of helpful resources and suggestions, including the Cite Black Author Database [Website] of scholars who identify as Black. The guide defines Citation Justice as “the act of citing authors . . . to uplift marginalized voices with the knowledge that citation is used as a form of power in a patriarchal society based on white supremacy.” The Research Consultant can help you find additional sources to bring in additional perspectives.

Citation Diversity Statements

In response to the lack of diversity in many academic fields, some scholars are choosing to include citation diversity statements (Zurn et al., 2020). This is a meaningful reflection tool to self-assess your citation practice. Generally, a citation diversity statement appears above the references section of a chapter. It includes three parts:

- In the first sentence, name your goal for citation diversity. Example: “The authors of this project worked to reference sources with fair gender and racial author inclusion.”

- In the next sentence, explain the process you used to ensure diversity. Example: “We searched for publications by people who self-identify as marginalized, including women and people of color.”

- In the last sentence, link to any resources used in your approach. Example: “We used the Cite Black Author Database [Website] to support this goal.”

Do your citation and attribution lists reflect the equity lens of this project and the goals of your own project’s description? If you were to write a citation diversity statement right now, what would you want people to know about your efforts?

Writing a citation diversity statement for your textbook is optional, but if you choose to write one, the Project Manager will add it to your {Course #} Front and Back Matter document.

Explicit and Implicit Bias in Textbooks

As an author of a textbook, you have your work cut out for you. The genre of textbook writing has a long history of being racist and exclusionary. As Charles W. Mills writes in The Racial Contract (1999), “Standard textbooks and courses have for the most part been written and designed by Whites, who take their racial privilege so much for granted that they do not even see it as political, as a form of domination.” Textbooks have often legitimized certain kinds of knowledge while marginalizing others. You have an opportunity to challenge this history and offer a different pathway to understanding.

Explicit bias in a textbook is easy to spot. It may involve the use of stereotypical examples or incorrect/dated terms to describe someone’s race, ethnicity, gender, economic status, and so forth. Explicit bias in textbooks can be pointed out on the page.

Implicit bias can be harder to spot in a textbook because it is based on what’s not on the page. It might be implied through tone. It might be a lack of discussion of scholars of color or an over-emphasis on “the greats” (who just happen to all be white and male). It might be found at the sentence level, with references to “men and women,” rendering invisible readers who don’t identify as either. For more descriptions of biases found in textbooks and curricular material, explore Seven Forms of Bias in Instructional Materials from the Myra Sadker Foundation [Website].

Lack of citation justice and diversity may reflect implicit bias. Authors do not set out to write biased textbooks, of course! Rather, we hope you’ll bring creative application of empathy to this pass through your chapters. This is your opportunity to put yourself in the reader’s place and imagine the text from their position.

Licenses and Attributions for Attributions and Citation Lists Through an Equity Lens

Open content, original

“Attributions and Citation Lists Through an Equity Lens” by Open Oregon Educational Resources is licensed under CC BY 4.0.

Open content, shared previously

“Critical Analysis of Copyright and Permissions” is adapted from “How Copyright Laws Created the Need for Open Licensing” by Michaela Willi Hooper for Open Oregon Educational Resources, licensed CC BY 4.0.

“Citation Justice and Diversity” is adapted from Attributions: Giving Credit by Michaela Willi Hooper for Open Oregon Educational Resources, licensed under CC BY 4.0, and Instructor Module | Ducks Have Integrity: Academic Conduct at UO by Rayne Vieger, licensed CC BY-NC-SA.

“Exlicit and Implicit Bias” is adapted from “The Work: Revising for Inclusion” by Stephanie Lenox and Abbey Gaterud for Open Oregon Educational Resources is licensed under CC BY 4.0.

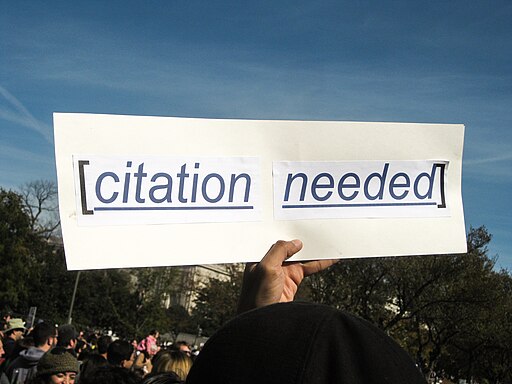

Figure Y2 9.3. “Citation needed” by futureatlas.com is licensed under Creative Commons Attribution 2.0 Generic.

References

Bali, M. (2019, October 29). Openness in whose interest? https://blog.mahabali.me/pedagogy/critical-pedagogy/openness-in-whose-interest-oerizona-opened19/

Mills, Charles W. The Racial Contract. Ithaca, NY: Cornell UP, 1999.

Sano-Franchini, J., Carter-Tod, S., Gruwell, L., Ihara, R., Hidalgo, A., & Ostergaard, L. (2022). Position Statement on Citation Justice in Rhetoric, Composition, and Writing Studies. https://cccc.ncte.org/cccc/citation-justice

Smith, C. A., Williams, E.L, Wadud, I.A., Pirtle, W.N.L, & The Cite Black Women Collective. (2021). Cite Black Women: A Critical Praxis (A Statement). Feminist Anthropology, 2(1), 10–17.

Zurn, P., Bassett, D. S., & Rust, N. C. (2020). The citation diversity statement: A practice of transparency, a way of life. Trends in Cognitive Sciences, 24(9), 669–672. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tics.2020.06.009