1.3 What is the Sociological Perspective?

The field of sociology is exciting and illuminating as it analyzes and explains important matters in our personal lives, communities, and the world. Most everything sociologists study can relate to us or someone we know. Sociology is the scientific and systematic study of human relationships, institutions, groups, and group interactions, societies, and social interactions, from small and personal groups to large groups. Sociologists’ subject matter is diverse, ranging from crime to religion, the family to the education system, group interaction, and societal perceptions of current issues.

Some researchers explore social problems from the micro-level, which means they look at small groups and individual interactions. Others use macro-level analysis to look at trends among and between large groups and societies. For example, if we are studying murder at the micro level, we would look at individual factors such as drug use that may have increased the risk of murder. In contrast, the macro level would look broadly at societal factors such as how poverty rates in a specific area may lead to higher rates of drug crime and ultimately homicide. We often call these discussions the “levels of explanation problem.” You can learn more about macro and micro sociology and how sociologists study social institutions and behavior from the “Macro and Micro Sociology” video in the Chapter Resources.

The sociological perspective looks at the intersection of the individual experience with social groups and society. We define society as a group of people living in a defined geographic area that has a common culture. Culture refers to the group’s shared practices, values, and beliefs. Culture encompasses a group’s daily life, from routine, everyday interactions to group members’ lives. It includes everything produced by a society, including all the social rules. To a sociologist, the decisions made by an individual do not exist in a vacuum. Cultural patterns and social forces influence people to select one choice over another. Over time, societies experience cultural shifts, which may result in new emerging patterns. Sociologists try to identify these general patterns by examining the behavior of large groups living in the same society and experiencing the same societal pressures.

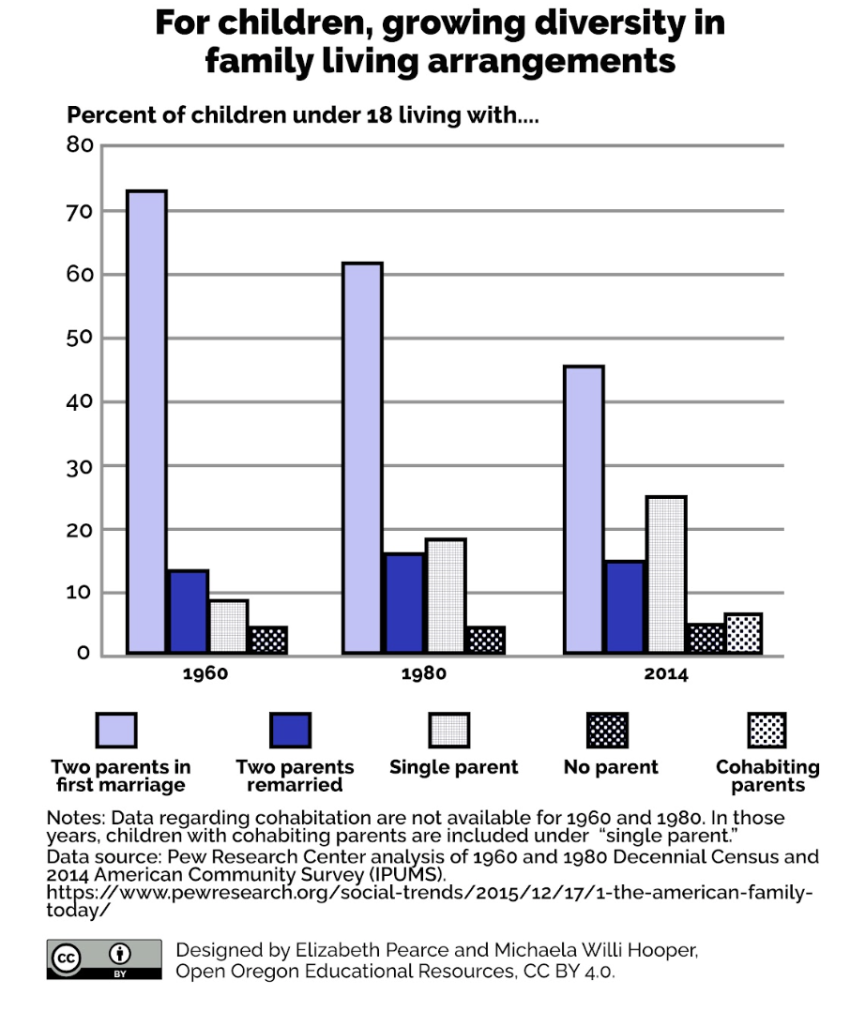

For example, sociologists have examined the changes in U.S. families (see figure 1.7). The “typical” family in the past decades consisted of married parents living in a home with their unmarried children. Today, the percentage of unmarried couples, same-sex couples, single-parent and single-adult households is increasing, as well as the number of expanded households, in which extended family members such as grandparents, cousins, or adult children live together in the family home (U.S. Census Bureau, 2020). Increasingly, single people and cohabiting couples are choosing to raise children outside of marriage through surrogacy or adoption.

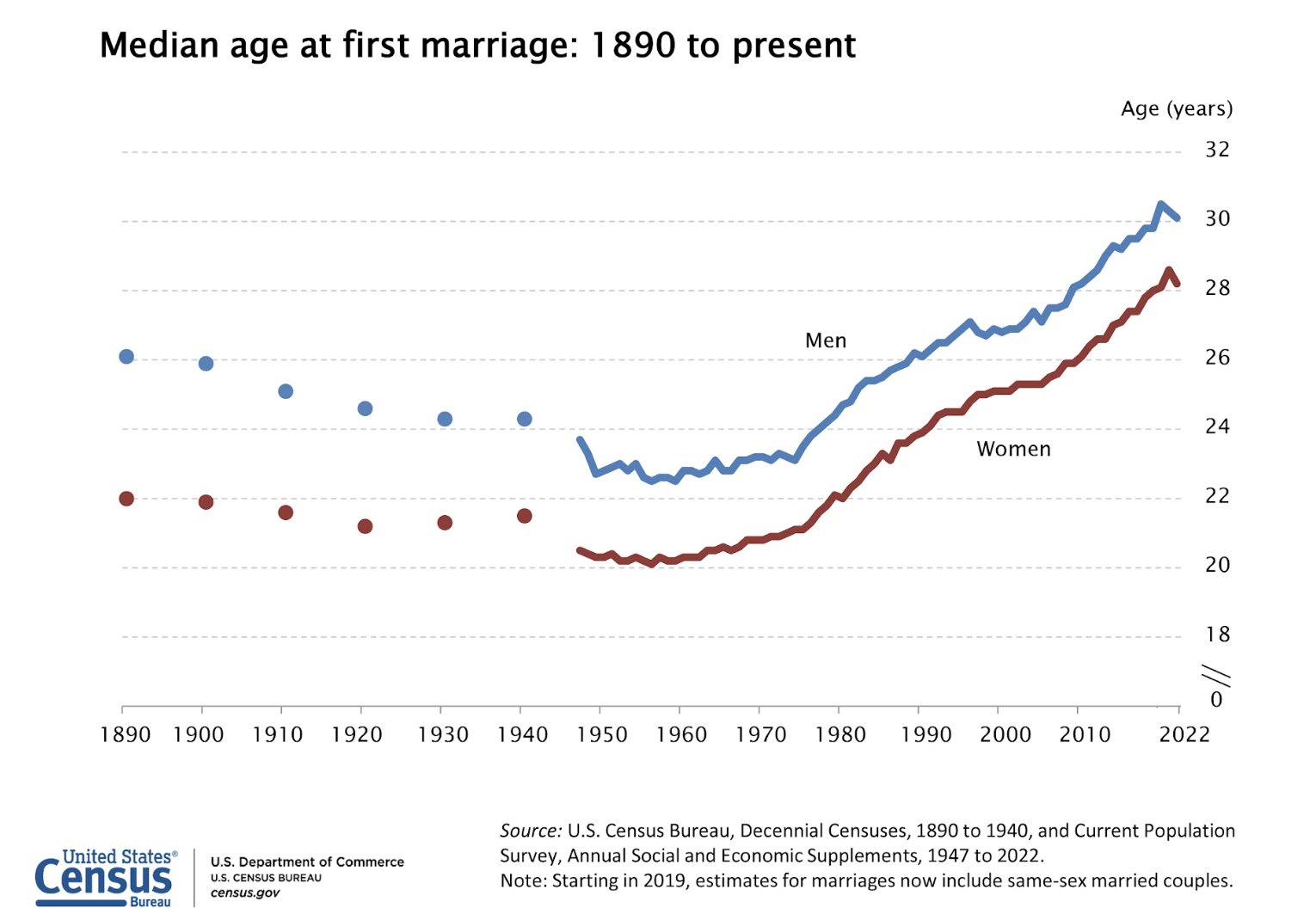

Some sociologists study social facts – the laws, morals, values, religious beliefs, customs, fashions, rituals, and cultural rules that govern social life – that may contribute to differences among family units. Do people in the United States view marriage and family differently over the years? Do they view them differently from people in other cultures? Do employment and economic conditions play a role in families? Other sociologists study the impact of new patterns, such as how family structure changes influence children and their changing needs for education, housing, and healthcare. Recently, sociologists have studied why people are delaying marriage until later in life or choosing not to get married at all (see figure 1.8). Sociologists identify and study patterns related to all kinds of contemporary social topics.

Social Institutions

A social institution is a group, organization, or social arrangement created to serve the needs of society with specific roles, norms, and expectations. They continually interact and influence each other. For example, family, government, religion, education, and media are just a few examples of social institutions. These institutions play key roles in individuals’ lives and the way a society functions. Sociologists argue that society, its institutions, and the individual are inseparable, and it is impossible to study one without the other. German sociologist Norbert Elias used the term “figuration” to describe the process of simultaneously analyzing the behavior of individuals and the society that shapes that behavior (1978). In simpler terms, figuration means that as one analyzes the social institutions in a society, the individuals using that institution need to be “figured” into the analysis.

For example, let’s look at religion. Many of us are socialized to believe in the same religion as our parents. While people individually experience religion, religion exists in a larger context as a social institution. For instance, a person’s religious practice is influenced by what the government dictates, holidays, teachers, places of worship, rituals, and more. These influences underscore the relationship between individual practices of religion and social pressures that influence the religious experience (Elias, 1978). Only a few decades ago, a Christian identity was very common among Americans. In the early 1990s, about 90 percent of U.S. adults identified as Christians. Today, two-thirds of adults are Christians (Pew Research Center, 2022). Although people possess and can exercise agency – the ability to make decisions about oneself and one’s behavior – sociologists emphasize that we need to look at more than human agency to understand the change in America’s religious composition.

Learn More: Negative Social Forces and Social Change

When sociologist Nathan Kierns spoke to his friend, Ashley, about the move she and her partner had made from an urban center to a small Midwestern town, he was curious about how the social pressures placed on a lesbian couple differed from one community to the other. Ashley said she felt her relationship was tolerated by others in the city. There had been little to no outright discrimination. Things changed when they moved to the small town for her partner’s job. For the first time, she found herself experiencing discrimination because of her sexual orientation. Some of it was particularly hurtful. Landlords would not rent to them. She is a highly trained professional, but has difficulty finding a new job. When Nathan asked her if she and her partner became discouraged or bitter about this new situation, she said that rather than letting it get to them, they decided to do something about it. She approached groups at a local college and several churches in the area. Together, they decided to form the town’s first Gay-Straight Alliance.

The alliance has worked successfully to educate its community about same-sex couples. It also worked to raise awareness about the kinds of discrimination that Ashley and her partner experienced in the town and how to prevent these experiences from happening to others. The alliance has become a strong advocacy group, and it is working to attain equal rights for lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, or LGBTQIA+ individuals. Kierns observed that this is an excellent example of how negative social forces can result in a positive response from individuals to bring about social change (Kierns, 2011). In this example of figuration, they were bonded to each other through mutual dependencies to create institutional and societal change.

The Sociological Imagination

Social location influences how people perceive and understand the world in which we live, and can make it challenging to be objective in all situations. To be objective means we look at something without bias (Carl, 2013). Subjective concerns, on the other hand, rely on judgments (rather than external facts) driven by personal feelings and opinions. To examine objective facts and the historical background of a situation, issue, society, or person (Carl, 2013), sociologists often study culture using the sociological imagination. C. Wright Mills described this concept in The Sociological Imagination (1959) as an awareness of the relationship between a person’s behavior and experience and the culture that shaped their choices and perceptions. It’s a way of seeing behavior related to history and social structure. Remember, though, that culture is a product of the people in a society. Sociologists do not treat the concept of “culture” as unchangeable.

In The Sociological Imagination (1959), Mills presented his classic distinction between personal troubles and public issues. If we think about personal troubles, we often blame ourselves for our issues. But Mills argues that it is too simplistic. Our troubles are often rooted in societal issues. Mills says the sociological imagination is a person’s ability to understand personal issues outside their control. If we were trying to understand unemployment, a macro factor, we would try to see how it influences people’s lives. Micro-sociological factors focus on interpreting personal viewpoints from an individual’s biography. Using only a micro-sociological perspective leads to an unclear understanding of the world from biased perceptions and assumptions about people, social groups, and society (Carl, 2013). In other words, we cannot understand a person without understanding where they grew up, the institutions they interact with, and other social factors.

To illustrate Mills’s viewpoint, let’s use our sociological imagination to understand the connected contemporary social problems of unemployment, crime, and COVID-19. We will start with unemployment, which Mills himself discussed. If only a few people were unemployed, Mills wrote, we could reasonably explain their unemployment by looking at individual traits. If so, their unemployment would be their problem. But when millions of people are out of work, unemployment is best understood as a public issue because “the very structure of opportunities has collapsed. Both the correct statement of the problem and the range of possible solutions require us to consider the economic and political institutions of the society, and not merely the personal situation and character of a scatter of individuals” (1959).

The unemployment rate rose dramatically during the severe economic downturn beginning in 2008, yet it has fallen to its lowest level since the COVID-19 pandemic. Once COVID-19 hit, millions of people in the United States lost their jobs. While some individuals are undoubtedly unemployed because of individual traits, a more structural explanation focusing on the lack of opportunity and forced shutdowns is needed to explain why so many people are unemployed. Though experienced as personal trouble, unemployment is a public issue. To learn more about this issue, you can read the article “Unemployment Rose Higher in Three Months of COVID-19 than It Did in Two Years of the Great Recession” in the Chapter Resources.

The global COVID-19 pandemic presented us with severe uncertainty for several years. From a sociological perspective, personal troubles during the pandemic ranged from families devastated by the passing of a loved one, essential medical workers caring for COVID-19 patients on the frontline, and a shutdown of our public space that confined many to their homes. Yet, we found the public health system was unprepared to manage this crisis (Blendon et al., 1989; Trevino et al., 1991; Williams and Rucker, 2000). Before the pandemic, there were concerns that the lack of quality access to health care in communities of color made the pandemic worse for people of color (Artiga, Garfield, Orgera, 2020). Additionally, the rise of hate crimes against Asian American and Pacific Islander (AAPI) communities during COVID-19 further illustrated how the sociological imagination can help us consider the personal impact of these hate crimes and the structural roots of this racism. The Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882 banned immigrants from China from entering the United States (History, 2018). People blamed Chinese immigrants for the economic insecurity and job decline that white Americans faced. During World War II in 1941, more than 112,000 Japanese Americans were forced into concentration camps after Japan launched an attack on Pearl Harbor (National Archives, 2022). Many Japanese Americans had no ties to Japan and had their homes and businesses taken from them after being incarcerated. With the sociological imagination, we can analyze the recurrence of Asian American discrimination when political issues arise. As seen in 2020, Asian Americans were victims of hate crimes once again because they were blamed for starting the COVID-19 pandemic. You can read more about the rise in Asian hate crimes during the pandemic in the article “More Than 9,000 Anti-Asian Incidents Have Been Reported Since The Pandemic Began” in the Chapter Resources.

Many public issues originate from issues within our social structure and culture that affect groups of people. Keep the concept of sociological imagination in mind as the coming chapters discuss how police brutality, immigration, mass incarceration, hate crimes, sexual harassment, and more are all rooted in societal issues that may impact us at the individual level.

Check Your Knowledge

Licenses and Attributions for What is the Sociological Perspective?

Open Content, Shared Previously

“The Sociological Imagination” is adapted from “What Is Sociology” by Tonja R. Conerly, Kathleen Holmes, and Asha Lal Tamang, Introduction to Sociology 3e, OpenStax, which is licensed under CC BY 4.0. Modifications by Shanell Sanchez, revised by Jessica René Peterson, licensed under CC BY 4.0, include remixing and expanding.

“What is the Sociological Perspective?” is adapted from “Sociology: Understanding and Changing the Social World (Barkan)” by Anonymous, which is licensed under CC BY-NC-SA 4.0. Modifications by Shanell Sanchez, revised by Jessica René Peterson, licensed under CC BY-NC-SA 4.0, include revising for clarity, recency, and brevity.

“What is the Sociological Perspective?” is adapted from “1.1: Sociological Perspective and Sociological Imagination” by Erika Gutierrez, Janét Hund, Shaheen Johnson, Carlos Ramos, Lisette Rodriguez, and Joy Tsuhako, SOC 106: Race and Ethnicity (Brenner), Long Beach City College, Cerritos College, and Saddleback College via ASCCC Open Educational Resources Initiative (OERI), which is licensed under CC BY-NC-SA 4.0. Modifications by Shanell Sanchez, revised by Jessica René Peterson, licensed under CC BY-NC-SA 4.0, include revising for clarity, recency, and brevity.

Figure 1.6. “#14 Multicultural Society” by UN Women Asia and the Pacific’s photostream is licensed under CC BY-NC-ND 2.0.

Figure 1.7. “For children, growing diversity in family living arrangements” by Elizabeth Pearce and Michaela Willi Hooper, Open Oregon Educational Resources, is licensed under CC BY 4.0.

Figure 1.8. “Figure MS-2” by the U.S. Census Bureau is in the Public Domain.

Figure 1.9. “GSAboard” by Philthecow is in the Public Domain.

Figure 1.10. “The Sociological Imagination” via Wikipedia is included under fair use.

the scientific and systematic study of human relationships, institutions, groups and group interactions, societies, and social interactions, from small and personal groups to large groups

social research focusing on small groups and individual interactions.

social research focusing on trends among and between large groups and societies

a group of people living in a defined geographic area that has a common culture

a group’s shared practices, values, and beliefs.

the laws, morals, values, religious beliefs, customs, fashions, rituals, and cultural rules that govern social life

rules a person must follow during probation

a group, organization, or social arrangement that is created to serve the needs of society

the process of simultaneously analyzing the behavior of individuals and the society that shapes that behavior, meaning that as one analyzes the social institutions in a society, the individuals using that institution need to be ‘figured’ into the analysis.

the unfair treatment of marginalized groups, resulting from the implementation of biases, and often reinforced by existing social processes that disadvantage racial minorities

a cumulation of cultural values and norms from a period

to look something without bias

to rely on judgments - rather than external facts - driven by personal feelings and opinions

an awareness of the relationship between a person’s behavior and experience and the culture that shaped their choices and perceptions (Mills, 1959)

property or violent crimes that are motivated by bias, usually related to one’s actual or perceived identity regarding race, ethnicity, color, country of origin, religion, gender or gender identity, sexuality, or disability

a form of prejudice that refers to a set of negative attitudes, beliefs, and judgments about whole categories of people, and about individual members of those categories because of their perceived race and ethnicity.