1.5 Colonialism and Race

Racial categories originated in colonialism. Colonialism is when one nation controls another by exploiting or conquering the population, often through force. What we now know as the United States has a long history of colonialism. In the 1400s, Britain, France, Spain, and the Netherlands established colonies in North America. Each country had different motivations, but they all wanted wealth and power. European colonization of North America expanded through Spanish colonists establishing themselves in present-day Florida in the 1500s and English colonists moving farther up the East Coast in the 1600s (National Geographic, 2023). For some time, North America’s Indigenous peoples were able to preserve their cultures and dignity through this period, despite facing violent dispossession by the colonists. Enslaved Africans were able to as well, amid the horrors of their forced transportation to North America and inhumane treatment by their enslavers (National Geographic, 2023).

By 1900, Indigenous populations were dwindling as tens of thousands were killed by white settlers and U.S. troops, whereas countless others died from disease contracted from people with European backgrounds. This genocidal killing of Native Americans is forever woven into the American fabric (Wilson, 1999). One example of genocide was the Wounded Knee Massacre in 1890. Armed U.S. officials surrounded the Sioux Tribe near Wounded Knee Creek, South Dakota. The Ghost Dancers, led by the Sioux Chief Big Foot, were attacked by the U.S. Army’s 7th Cavalry. A shot was fired, and what followed was the killing of more than 150 Native Americans, most of whom were women and children. This massacre was preventable, and it demonstrated the abuse that the U.S. government inflicted upon Native Americans for not surrendering and complying.

Both religion and science have been instrumental in establishing colonial domination. Research has found that religious groups used religious arguments about the moral superiority of “technologically advanced” civilizations to legitimize slavery, murder, rape, and dispossession of groups perceived to be “savages.” In nations now considered “Western societies,” Christian colonizers argued that Indigenous groups and enslaved groups needed spiritual salvation (ignoring pre-existing religions they considered “primitive”). Southerners forcibly turned people away from their traditional belief systems and forcibly turned them toward the Christian faith (Ashcroft, Griffiths, and Tiffin, 2013). Science devised a more formal value system to classify physical traits (skin color, “bloodlines,” head shape, and more) to establish its claim over the land and resources of Indigenous groups and justify slavery (Newitz, 2014; Yale, 2016). Social Darwinism, the idea that people survive in society because they are the strongest, or the idea of the “survival of the fittest,” a phrase proposed by the British philosopher and scientist Herbert Spencer. Spencer created racist biological theories used to craft and legitimize racist social policies (Dennis, 1995; Jackson and Weidman, 2005; Tucker, 2007). We will explore each of these issues further in later chapters.

Sociologists have played a role in advancing colonialism, along with every other scientific field. From Emile Durkheim describing Aboriginal people as primitive to British sociologist Francis Galton drawing on eugenics to justify the sterilization of poor people, sociology has contributed to colonialism (Ruswick, n.d.). Eugenics is the practice of eliminating specific populations by selectively mating people with specific desirable hereditary traits. They argued eugenics could reduce “human suffering by breeding out” diseases, disabilities, and so-called undesirable characteristics from the human population (History, 2019). While sociology has also invested in developing the theoretical tools to undo the harm of scientific racism, this colonial history is yet to be fully redressed in sociology and other fields (Merton and Storer, 1979). Colonialism has spread distinct patterns of ideology, such as the denigration of Black and Indigenous people through the use of blackface or cultural appropriation.

Social Construction of Whiteness

The concept of whiteness explores the social construction of what it means to be white and how societies establish white culture as the “norm” for social reality. Whiteness studies teach us to think critically about how social life is organized around white experiences. Whiteness is hegemonic, which means that it is an ideology that was established over time, first through violent political dominance and later through cultural institutions that created the idea that white culture is the natural order. Social institutions funnel white culture so that it is pervasive: it’s the key lens of history and art; it’s how we learn about science; it’s the representations we grow up within the media; it’s white people filling most positions of authority. Whiteness is everywhere, and while it is the center of colonial nations, whiteness also goes unexamined in day-to-day life. White people are not asked, “Where are you from?” They are not required to verify that they are American constantly. White people don’t have to think too deeply about why there are no Indigenous people in their schoolbooks. White people don’t experience firsthand what it’s like to be made to feel uncomfortable at work because of their race. White people don’t fear being mistreated by authority figures simply because of the color of their skin.

Whiteness is both privilege and power; it means being on top of the social hierarchy but taking the hierarchy for granted. One example of this is when white politicians took offense at being called white during a Senate debate while they were voting to remove protections for people of color. Power is quintessential to representations of whiteness and otherness because, whether the difference is portrayed positively or negatively, the other is constructed against a hegemonic ideal of whiteness, allowing white people to distance themselves from, and also negate, structural racism. If you want to learn more, view the video “GOP Senator Tommy Tuberville Disputes Defining White Nationalists as Racist” in the Chapter Resources.

People have come to understand that “overt” forms of racism are not permissible and often avoid being associated with the label “racist.” Some people will say things like “I don’t see race, I just see people,” or “We are all part of the human race; why can’t we all just get along?” This discourse is a ploy: white people can afford to tune in and out of race discussions. To say that they don’t recognize race is to say: “I don’t want to acknowledge how my life chances have been enhanced by my whiteness.” To say that they “just see people” is to also deny the impact that race has on the lives of people of color, who receive daily reminders of how race negatively impacts their safety, acceptance, and progress.

The flip side of “I don’t see race” is the fact that white people place people of color into broad categories and deny them their individuality. We see this at the social level when people of color are put into the position of explaining crime and “deviance” within their communities. At the interpersonal level, white people will “confuse” people of color because they have limited contact and interest in people who are not white. An infamous example involved Black American actor Samuel L. Jackson, who rightly refused to smooth over the racist “mistake.” These examples illustrate how whiteness pushes individuals into broad categories, even though white people see themselves as individuals who aren’t influenced by race.

White Privilege

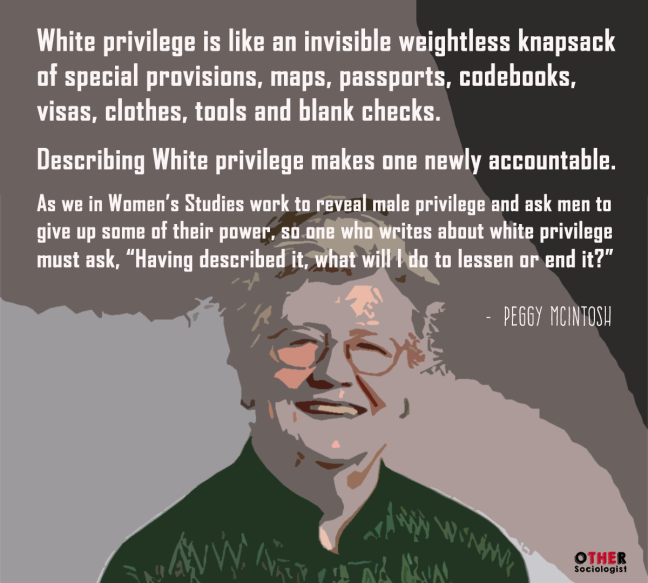

American scholar Peggy McIntosh introduced the idea of white privilege, which is the special benefits, protections, and access to power conferred upon white people. White privilege allows them to advance in life without conscious awareness of racial discrimination (McIntosh, 1989). She noticed that even when male colleagues were willing to support women’s efforts to increase gender equity, they were not willing to give up their status and power. Having tried to include women of color in her feminist activities with little successful engagement, she came to see how she, as a white woman, had also been reticent to give up her benefits to make feminism truly inclusive of women of color. She notes that educated white people like herself are raised to notice the “bad” aspects of racism, but not the benefits that make her life easier.

She came to realize that whiteness was like an “invisible knapsack” she carried around with her, which protected her from noticing the advantages of race. Noticing her racial privileges, she understood the myth of meritocracy, for in the bag of whiteness, she found the key to open many doors that women of color cannot access. Her skin color was “an asset” that helped her secure a better education; it made it easy to take for granted that she belonged to the broader culture that facilitated her success, despite the gender inequalities she fought.

The “color blind” approach to feminism is nowadays referred to as white feminism. White feminism is the pursuit of gender equity in a way that systematically ignores – and benefits from – the impact of race, power, and dominance of white women in society. While white women are disadvantaged by white men, their white privilege gives them advantages over people of color of all genders. So, even with gender, class, and other disadvantages, white women must recognize that they have greater resources at their disposal in the fight for equal rights. Feminism positions equality among white men, ignoring the needs, experiences, and knowledge of people of color.

White privilege is the total of various invisible forms of power that white people have, regardless of their social standing. White people are generally made to feel comfortable wherever they go, or at least oblivious of their race. People of color are routinely made to feel alienated, and so they are less confident that they will be treated fairly based on their skin color. There are various subtle and overt forms of hostility and violence to which white people are never exposed. White privilege is a special form of cultural power; it is the “permission to escape or to dominate.” That is, it is the ability to be oblivious to race (including unconscious bias) or to wield race to one’s advantage (willful discrimination). White privilege is a call to action to actively join anti-racism. This means not expecting people of color to become more like white people, but thinking about how to change the system and elevate the power, potential, comfort, inclusion, leadership, safety, and justice of people of color.

Learn More: D.C. Makes It A Crime To Wear Masks, So Why Was A Group of White Nationalists Able To?

In Washington, D.C., a group of white nationalists made a public demonstration on February 8, 2020. The Patriot Front promoted their ideology in a protest. Labeled as a hate group by the Southern Poverty Law Center, they embraced fascism and marched to spread that viewpoint (Austermuhle, 2020). There, they donned white face masks to cover their identities. However, D.C. law prohibits the usage of masks to disguise one’s face while participating in illegal activities and threatening others, a law that was set in place decades before reducing Ku Klux Klan attacks decades prior. The group chanted that they wanted to reclaim America, and argued that Jewish people, Marxists, and “anti-white” government individuals were trying to get rid of white people. The Patriot Front is just one example of a white nationalist group. Many others support these extremist ideas, equating the rising racial diversity with an attack on the white race. Within the United States, white extremism is our greatest threat to domestic terrorism (Reyna et al., 2022). This ideology attacks people of color and amplifies discrimination. A possible contributor to these attitudes is where one grew up. In a 2020 study, researchers found that the less racially diverse an area is, the more likely individuals are to believe racist stereotypes. Then find some research that backs up the assertion that interaction helps reduce negative feelings. Grounding this part in research will reduce the chance of misinterpretation (Bai et al., 2020). Interacting with different racial and ethnic groups may reduce negative feelings.

In the case of The Patriot Front, white supremacist views can stem from less diverse backgrounds and upbringings. During the Patriot Front protest, the group received no repercussions despite its extremist views on ethnic and racial minorities. The distinction between protesting and intimidating others is difficult to define, but the anti-mask law only applies to people who are threatening others while wearing a mask. Since they were not actively threatening to hurt anyone, they had the constitutional right to protest their views while wearing masks. However, this protest highlighted the protection of white individuals versus other racial minorities. In comparison to the Black Lives Matter protests after George Floyd’s murder, the Patriot Front was treated differently. Not a single one of the Patriot Front members was arrested or detained, nor were they tear-gassed or beaten like the Black Lives Matter protesters. Instead, they were escorted by police officers. Despite being a hate group, the Patriot Front members were protected in a way that other minority protests have not been.

Check Your Knowledge

Licenses and Attributions for Colonialism and Race

Open Content, Shared Previously

“Colonialism and Race” is adapted from “Sociology of Race” by Dr. Zuleyka Zevallos, The Other Sociologist, which is licensed under CC BY-NC-ND 3.0. Modifications by Shanell Sanchez, revised by Jessica René Peterson, licensed with author permission under CC BY-NC-SA 4.0, include revising for a U.S. context.

Figure 1.19. Graphic by Dr. Zuleyka Zevallos, The Other Sociologist, is licensed under CC BY-NC-ND 3.0.

Figure 1.20. “The Patriot Front is sloppy” by Joe Flood is licensed under CC BY-NC-ND 2.0.

the deliberate destruction and systematic killing of targeted groups of vulnerable people

a group of people living in a defined geographic area that has a common culture

scientific explanations of things happening around us, such as patterns in social behavior, and how certain things are related

the scientific and systematic study of human relationships, institutions, groups and group interactions, societies, and social interactions, from small and personal groups to large groups

ideology that “appropriates the methods and legitimacy of science to argue for the superiority of white Europeans and the inferiority of non-white people whose social and economic status have been historically marginalized”

a group’s shared practices, values, and beliefs.

a category of people grouped because they share inherited physical characteristics that are identifiable, such as skin color, hair texture, facial features, and stature

a form of prejudice that refers to a set of negative attitudes, beliefs, and judgments about whole categories of people, and about individual members of those categories because of their perceived race and ethnicity.

the special benefits, protections, and access to the power conferred onto white people

the unfair treatment of marginalized groups, resulting from the implementation of biases, and often reinforced by existing social processes that disadvantage racial minorities

the pursuit of gender equity in a way that systematically ignores—and benefits from—the impact of race, power, and dominance of white women in society

widely held beliefs or assumptions about a group of people based on perceived characteristics.