2.3 Racism

In the previous section, we focused on prejudice and discussed how prejudice can often be common regarding race and ethnicity. “Prejudice is a matter of feeling; it’s a hostile or dismissive attitude, a feeling toward people we find different from ourselves in some way, and some way that we take as significant, but racism is more than that” (PBS Fredrickson, 2003). Racism is a form of prejudice that refers to a set of negative attitudes, beliefs, and judgments about whole categories of people, and about individual members of those categories because of their perceived race and ethnicity. It is a set of beliefs that attempts to justify feelings and make the case that the differences we find between racial and ethnic groups are innate, permanent, and are the basis for action or even for an institution that will be based on these differences. In other words, it tends to turn into a kind of inequality or hierarchy based on these ideas. It begins with prejudice because it is based on stereotypes that are learned and perpetuated in society.

Importantly, racism also describes the system of racial inequality, based on the belief that some groups are innately superior to other groups. Racism rests on the prejudices (attitudes), symbols (including language), actions, and policies that reproduce the false ideology that other groups are inferior to white people. Simply stated, racism is prejudice plus power (Barndt, 1991). Racism involves power structures – such as historical and cultural relations established through colonialism and social institutions (like criminal justice, education, media, and science) – in which one group has the power to carry out systematic unequal treatment through the institutional policies and practices of the society by shaping the cultural beliefs and values that support those racist policies and practices (dR workbook, 2020).

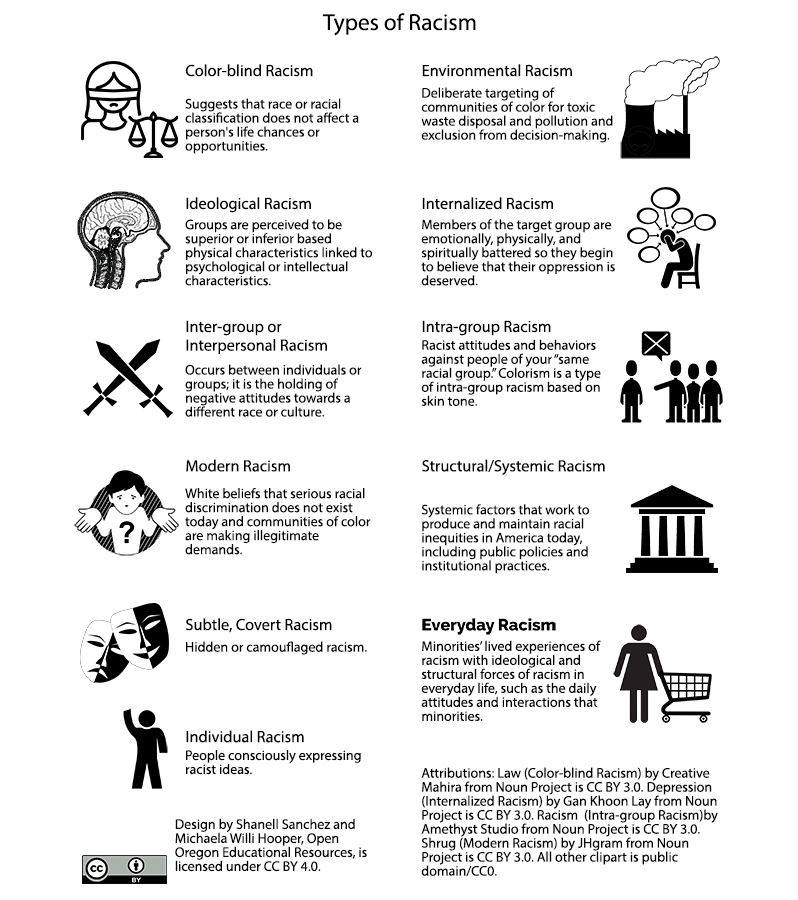

People misunderstand and think that racism only means overt acts of oppression. Racism encompasses both covert prejudice and systemic forms of discrimination. Discrimination – discussed further in the next section – refers to the unfair treatment of marginalized groups, resulting from the implementation of biases, and often reinforced by existing social processes that disadvantage racial minorities. People can be unaware of how they both benefit from and reproduce racism, and their words and actions may have unintended consequences, even if they do not mean to consciously discriminate. Regardless, racism does not require conscious intent. Racism is so deeply ingrained in our socialization that it affects everyone, whether they are benefiting or not. See Figure 2.5 for a description of different forms of racism.

Racism is a marriage of racist policies and racist ideas that produce and normalize racial inequities, according to Ibram X. Kendi (2020). Kendi defines a racist as someone who supports a racist policy through their actions or inaction, or by expressing a racist idea. Further, racial inequity is defined as two or more race-ethnic groups not standing on equal footing, which is a result of racist policies or ideas (Kendi, 2020). For Kendi, the polar opposite of a racist is an anti-racist, one who supports an anti-racist policy through their actions or expresses an anti-racist idea. To say that one is not racist is a hollow statement, as it is devoid of action. An example of an anti-racist criminal justice policy would be to eliminate criminal justice fees and reform fines. These policies had an explicitly racist past and asked more of those with the least resources (Sanders and Leachman, 2021). The terms stereotype, prejudice, discrimination, and racism are often used interchangeably in everyday conversation, but sociologists do not view them as the same.

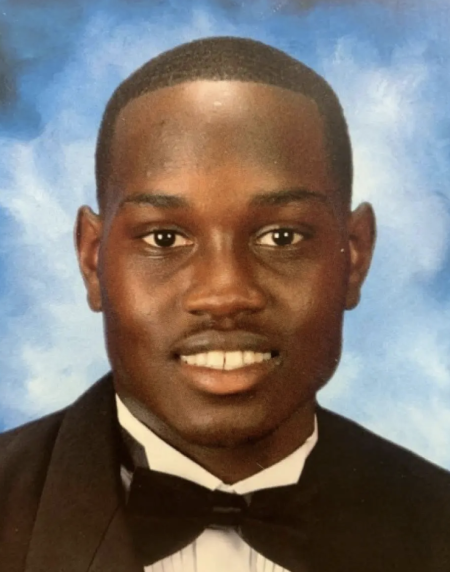

Learn More: Ahmaud Arbery’s Murder Fueled by Racism

In February 2020, Ahmaud Arbery was out for a jog. Little did he know he was being followed by Travis McMichael, Gregory McMichael, and William Bryan through the streets of Brunswick, Georgia. Within minutes, he was murdered in Satilla Shores. The men stated that they saw Ahmaud enter a house under construction, so they assumed he was breaking in. They grabbed their guns and followed him in their pickup truck. Ahmaud was stalked and attacked by Travis and Gregory. While Ahmaud tried to defend himself, Travis shot him three times. One of the offenders, Gregory McMichael, was a former police officer and investigator in the local District Attorney’s Office. He later told police that Ahmaud and his son had struggled over his son’s shotgun. In their initial police report, he said Travis McMichael shot Ahmaud after the latter attacked him. They claimed they were going to conduct a citizen’s arrest.

None of the men pursuing Ahmaud were arrested for months. After video footage from William’s phone was posted online, social media users were outraged and protested for justice. After three months, all three men were arrested, with Travis and Gregory sentenced to life in prison while William received 35 years in prison. The backlash from the video caused conversations about the violence Black Americans face. More specifically, how common activities like jogging and looking inside construction sites could suddenly be labeled as “criminal behavior” when that person is Black. Ahmaud had not been the only person to visit the house. Security cameras showed kids, adults, and neighbors entering the house as well. However, none of them had suffered the same fate as Ahmaud Arbery. Ahmaud was, simply put, a victim of explicit racism.

Interpersonal and Everyday Racism

Individual racism, sometimes called interpersonal racism, is the type of racism that occurs between individuals and is what most people think of when using the term racism. It refers to the beliefs, attitudes, and actions of individuals that support or perpetuate racism. Individual racism can occur at both an unconscious and conscious level, and can be both active and passive (Wijeysinghe, Griffin, and Love, 1997). Individual racism refers to an individual’s racist assumptions, beliefs, or behaviors and is “a form of racial discrimination that stems from conscious and unconscious, personal prejudice” (Henry and Tator, 2006). This form of racism can be intentional or unintentional. Telling a racist joke, believing in the inherent superiority of white people, and crossing the street to avoid passing a Black man are just a few examples.

Racism is often understood as an individual state of being, as in someone is or isn’t racist. Racism, however, is not merely a personal attitude; it is a radicalized system of power maintained by violence. In North America, an individual can perpetuate this system without even being conscious of their actions (Simmons University Library, 2020). All people hold unconscious biases, and it requires education and ongoing critical reflection to identify, manage, and overcome these prejudices. Patterns of interpersonal racism shift over time. Individual racism can include being made to feel unwelcome in social settings, but it also extends to missing out on jobs and other, more overt forms of discrimination. The cumulative effect of interpersonal racism is that people of color feel apprehensive about their safety and futures.

Although women are thought to be more empathetic than men and thus are less likely to be racially prejudiced, past research has indicated that the racial views of white women and men are very similar and that the two genders are about equally prejudiced (Hughes and Tuch, 2003). This similarity supports group threat theory, in that it indicates that white women and men are responding more as white people than as women or men, respectively, in formulating their racial views. We also saw this play out in recent presidential elections, as discussed in Chapter 1. Additionally, education levels and geographic location can shape attitudes and impact interpersonal racism. Less educated white people are usually more racially prejudiced than those with higher levels of education, and Southerners may be more prejudiced than non-Southerners (Carter et al., 2014; Pew Research Center, 2016b). For example, a 2016 study found that 62 percent of Republicans without a college degree saw immigrants as a burden to the country, while 42 percent of Republicans with a college degree agreed with that sentiment. In this same study, participants were asked if increased racial and ethnic diversity made the United States better; 48 percent of non-college Republicans agreed, while 68 percent of college Republicans agreed.

Everyday racism connects lived experiences of racism with ideological and structural forces of racism in everyday life, such as the daily attitudes and interactions that people of color face, which in turn reproduce racism (Essed, 1991). Racism is maintained in taken-for-granted ways, even when people are unaware of it, through the repetitive or familiar practices of everyday situations. An example of everyday racism is the question, “Where are you from?” People who ask this question think they are satisfying their curiosity, but in fact, this question has racist assumptions that the person they are talking to is “not from here” (Zevallos, 2017). As this question is not usually asked of white people, it is a reminder that race mediates who is counted as American and who is excluded. “Where are you from?” is a boundary marker; a reminder to non-Indigenous people of color that racism is ever-present, as expressed in its twin sentiment, “Go back to where you came from!” a racist slur used against migrant people of color, even if they were born in the United States.

Perceived Reverse Racism

Although most sociologists do not think reverse racism is real, Americans are still split on whether reverse racism exists. Perceived reverse racism is defined as the perceived concept of discrimination, oppression, and prejudice directed toward white individuals because of their race (Peucker, 2023). A common idea underlying the “perceived reverse racism” discourse is that white people today shouldn’t have to pay for the oppression that happened in the past. The idea of “reverse racism” is prevalent amongst white people who hold two paradoxical beliefs: 1) Society is not racist; and 2) people of color get special privileges because of their heritage. However, based on the definition of racism as a concept that includes prejudice and power, as discussed earlier, “reverse racism” against white people in the United States is not possible.

White people today mostly understand that saying negative things about people of color is not acceptable. In interviews with researchers, they will talk about their racist relatives, without thinking of themselves as racist (Bonilla-Silva, Lewis, and Embrick, 2004). They will share one-off examples where they’ve had a positive encounter with a person of color. Yet their negative experiences with people of color take on a different meaning. The positive is an example of a “good” individual. The negative example is an indictment of the entire group or racial prejudice. White people will evoke this concept when they say they don’t understand why some people of color who experienced colonialism still talk about racism when other white groups aren’t “allowed” to talk about “racism.” The “perceived reverse racism” narrative is a way white people air out racist ideals without thinking of themselves as racist, oftentimes referred to as “color-blind racism.”

Learn More: Fear of a Brown Planet

Racism is more than just saying something negative about a member of another group and is often an institutional process connected to historical social relations. Racism describes a system of discrimination at school, at work, in the media, in politics, and through other social institutions. The false concept of reverse racism ignores these institutional experiences of oppression. When a person of color voices a negative view of white people, this is a stereotype (an attitude or belief), but it does not carry the same institutional power as when a white person does the same thing.

Check Your Knowledge

Licenses and Attributions for Racism

Open Content, Original

“Racism” by Shanell Sanchez and Catherine Venegas-Garcia, revised by Jessica René Peterson, is licensed under CC BY 4.0.

Open Content, Shared Previously

Figure 2.6. The photo of Ahmaud Arbery is included under fair use.

Figure 2.7. Image by Hrt+Soul Design is licensed under the Unsplash License.

All Rights Reserved Content

Figure 2.8. “Aamer Rahman (Fear of a Brown Planet) – Reverse Racism” by FEAR OF A BROWN PLANET is shared under the Standard YouTube License.

an individual attitude based on inflexible and irrational generalizations about a group of people and literally means “judging before.”

a category of people grouped because they share inherited physical characteristics that are identifiable, such as skin color, hair texture, facial features, and stature

shared social, cultural, and historical experiences of people from common national or regional backgrounds that make subgroups of a population different

a form of prejudice that refers to a set of negative attitudes, beliefs, and judgments about whole categories of people, and about individual members of those categories because of their perceived race and ethnicity.

widely held beliefs or assumptions about a group of people based on perceived characteristics.

a group of people living in a defined geographic area that has a common culture

the unfair treatment of marginalized groups, resulting from the implementation of biases, and often reinforced by existing social processes that disadvantage racial minorities

the process through which people are taught to be proficient members of a society.

the type of racism that occurs between individuals, including the beliefs, attitudes, and actions of individuals that support or perpetuate racism. Also called interpersonal racism.

the racism people of color are exposed to in the repetitive or familiar practices of everyday situations, including unconscious attitudes and interactions

the perceived concept of discrimination, oppression, and prejudice directed toward white individuals because of their race