2.4 What is Discrimination?

The term discrimination has been used a bit throughout this chapter, but what does it mean, and how does it differ from prejudice and racism? Discrimination, as defined previously, is the unfair treatment of marginalized groups, resulting from the implementation of biases, and often reinforced by existing social processes that disadvantage racial minorities. For example, refusing to consider the job application of a person of color (an act of discrimination) based on racial markers, like their name (prejudice), replicates the excessive rejection these candidates already experience because of widespread racism (Martin, 2009). It is illegal to discriminate based on your race, ethnicity, or national origin. Some forms of discrimination are overt, which is a blatant act of discrimination. For example, a landlord violates the law if they tell you they do not rent to Black people. Likewise, it is illegal for an employer to refuse to hire a person of color because of that person’s race, ethnicity, or national origin (ACLU, 2024). Some forms of illegal discrimination may be subtler or covert. A mortgage company may adopt policies that cause unjustified and disproportionate harm to people of a particular race, ethnicity, or national origin. We will hear about this more when we discuss redlining in Chapter 4. Another example may be refusing to hire anyone with any sort of criminal record. Research has found that this disproportionately hurts Black and Latinx job applicants, who are more likely than white applicants to have criminal records in the current criminal justice system.

History of Legal Racial Discrimination

Black people have long faced maltreatment in the United States, beginning during the colonial period when people were forcibly transported from their homelands to be sold and abused as slaves in the Americas. During the 1830s, white mobs attacked African Americans in cities throughout the nation, including Philadelphia, Cincinnati, Buffalo, and Pittsburgh. This mob violence led Abraham Lincoln to lament “the worse than savage mobs” and “the increasing disregard for law which pervades the country” (Feldberg, 1980:4). The mob violence stemmed from a “deep-seated racial prejudice…in which white people saw Black people as ‘something less than human’” (Brown, 1975:206) and continued well into the 20th century, when white people attacked African Americans in several cities, with at least seven anti-Black riots occurring in 1919 alone that left dozens dead.

Between the late 1800s and mid-1900s, the Jim Crow system represented a formal, codified system of racial apartheid that prevailed not just in the South but in the entire nation. During the Jim Crow laws and era of racism, segregation was enforced in all facets of life, and several thousand African Americans were murdered via lynchings (Litwack, 2009; National Geographic, 2024). Black people were not the only targets of White mobs back then (Dinnerstein and Reimers, 2009). As immigrants from Ireland, Italy, Eastern Europe, Mexico, and Asia flooded into the United States during the 19th and early 20th centuries, they, too, were beaten, denied jobs, and otherwise mistreated. During the 1850s, mobs beat and sometimes killed Catholics in cities such as Baltimore and New Orleans. During the 1870s, white people rioted against Chinese immigrants in cities in California and other states. Hundreds of Mexican people were attacked or lynched in California and Texas during this period.

The Jim Crow system was upheld by local government officials and reinforced by acts of terror perpetrated by vigilantes. In 1896, the Supreme Court established the doctrine of separate but equal in Plessy v. Ferguson, after a Black man in New Orleans attempted to sit in a railway car for white people only. In legal theory, Black people received “separate but equal” treatment under the law – in actuality, public facilities for Black people were nearly always inferior to those for white people, when they existed at all. In addition, Black people were systematically denied the right to vote in most of the rural South through the selective application of literacy tests and other racially motivated criteria (PBS, 2024). Plus, the idea that people could ever be considered equal when legal separation is required is ironic.

Nazi racism in the 1930s and 1940s helped awaken some Americans to the evils of prejudice in their own country. Against this backdrop, a monumental two-volume work by Swedish social scientist Gunnar Myrdal (1944) attracted much attention when it was published. The book, An American Dilemma: The Negro Problem and Modern Democracy, documented the various forms of discrimination facing Black people. The “dilemma” referred to by the book’s title was the conflict between the American democratic ideals of egalitarianism, liberty, and justice for all and the harsh reality of prejudice, discrimination, and lack of equal opportunity. Using the common term for African Americans of his time, Myrdal wrote optimistically,

If America in actual practice could show the world a progressive trend by which the Negro finally became integrated into modern democracy, all mankind would be given faith again—it would have reason to believe that peace, progress, and order are feasible.… America is free to choose whether the Negro shall remain her liability or become her opportunity. (Myrdal, 1944:1121–1122)

Unfortunately, Myrdal was too optimistic, as legal segregation did not end until the civil rights movement won its major victories in the 1960s. Racism was systematic and involved blatant bigotry, firm beliefs in the need for segregation, and the view that Black people were biologically inferior to white people. For example, Black people were not allowed in white people’s schools or to eat in restaurants designated “whites only.” In the early 1940s, for example, more than half of all white people thought that Black people were less intelligent than white people, more than half favored segregation in public transportation, more than two-thirds favored segregated schools, and more than half thought white people should receive preference over Black people in employment hiring (Schuman, Steeh, Bobo, and Krysan, 1997).

Challenging Segregation and the Changing Nature of Prejudice

From May until November 1961, more than 400 Black and White Americans risked their lives – and many endured savage beatings and imprisonment – for simply traveling together on buses and trains as they journeyed through the Deep South. Deliberately violating Jim Crow laws to test and challenge a segregated interstate travel system, the Freedom Riders met with bitter racism and mob violence along the way, sorely testing their belief in nonviolent activism (PBS, 2024). Freedom riders were challenging the non-enforcement of the U.S. Supreme Court decisions Morgan v. Virginia (1946) and Boynton v. Virginia (1960), which ruled that segregated public buses were unconstitutional.

Even after segregation ended, improvement in other areas was slow. Thus in 1968, the so-called Kerner Commission, appointed by President Lyndon Johnson in response to the 1960s urban riots, warned in a famous statement, “Our nation is moving toward two societies, one Black, one White – separate and unequal” (1968:1). The atrocities of overtly racist Nazi Germany and the achievements of the Civil Rights Movement began to change thoughts about segregation and Jim Crow-era policies. By no means is racial and ethnic prejudice extinct in the United States; racial discrimination, or unfair treatment based on race, occurred long after slavery ended. However, the nature of prejudice in the United States has changed during the past half-century.

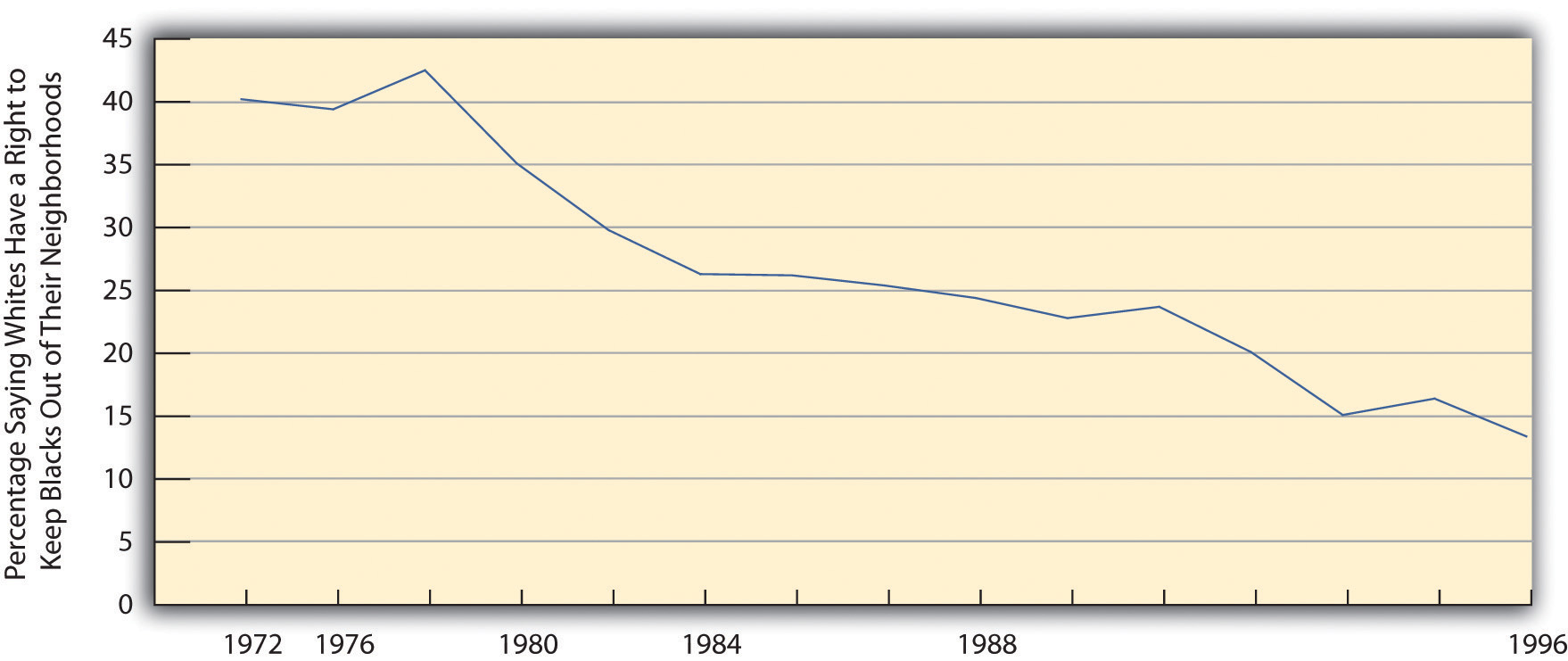

Today, fewer white people favor segregation. As just one example, with General Social Survey data, white people’s support for segregated housing declined dramatically from about 40 percent in the early 1970s to about 13 percent in 1996. This shows changing support at a time when Civil Rights was at the forefront of discussion. Unfortunately, national surveys no longer include many of the questions asked 50 years ago; for example, the General Social Survey does not ask about segregated housing after 1996, which does not allow us to look at comparison data today.

However, stereotypes about Black people have prevailed, and historical oppression is often ignored when considering current disparities. And have negative impacts on people of color. For example, some people believe the higher rate of poverty in the Black population is because they do not work hard and oppose government policies to help them. In effect, this stereotype blames Black people for their low socioeconomic standing and involves beliefs that they simply do not want to work hard. “Black people are still stereotyped and blamed as the architects of their disadvantaged status” (Bobo, Kluegel, and Smith, 1997:31). These views lead white people to oppose government efforts to help African Americans.

Evidence for this modern form of prejudice is often found in white people’s responses to two GSS questions that asked, respectively, whether African Americans’ low socioeconomic status is due to their lower “inborn ability to learn” or to their lack of “motivation and willpower to pull themselves up out of poverty” (GSS, 2016). While only 9.2 percent of white people attributed Black people’s status to lower innate intelligence (reflecting the decline of Jim Crow-era racism), almost 52 percent attributed it to their lack of motivation and willpower. Although this reason sounds “kinder” and “gentler” than a belief in Black people’s biological inferiority, it is still one that blames Black people for their low socioeconomic status.

Despite the civil rights movement’s successes, 30 years later, writer David K. Shipler (1997:10) felt compelled to observe that there is “no more intractable, pervasive issue than race” and that when it comes to race, we are “a country of strangers.” Sociologists and other social scientists have warned since then that the conditions of people of color have been worsening (Massey, 2007; W. J. Wilson, 2009). In 2023, about half of Black Americans in a Post-Ipsos study with more than 1,200 people said racism would get worse over the rest of their lifetimes. Nearly 6 in 10 said it is more dangerous to be a Black teen today than when they grew up, and they worry a loved one will be harmed. They also found that three out of four Black adults are “very” or “somewhat” concerned about states stopping the teaching of Black history, that public schools are banning books that touch on the topic of racism, and states stopping public schools from teaching the history of racism in America (Washington Post). Shipler and others may see that time has not made issues of race go away or improve, but has furthered the negative experiences of people of color.

Systemic Racism and Connections to Criminal Justice

Systemic racism – also referred to as institutional or structural racism – describes patterns of discrimination based on race and refers to how racism is embedded in the fabric of society and how institutional processes are used to maintain systematic discrimination. This type of racism exists across a society, within and between institutions and organizations. It refers to the complex interactions of large-scale societal systems, practices, ideologies, and programs that produce and perpetuate inequities for racial minorities. For example, the U.S. government secretly tested war chemicals on people of color to see the effects on their skin because there was a stereotype that Black skin could withstand the chemicals (Dickerson, 2015). The key aspect of systemic racism is that these macro-level mechanisms operate independently of the intentions and actions of individuals, so that even if individual racism is not present, the adverse conditions and inequalities for racial minorities will continue to exist (Gee and Ford, 2011).

Individual experiences of discrimination are much more widespread and are happening across multiple spheres of life. Discrimination and prejudice have impacted the criminal justice system in so many ways. Some examples of systemic racism that we discuss in sociology and criminology are government surveillance, social segregation, police brutality, mass incarceration, and mandatory minimum sentences, to name a few. For example, research has found Black Americans are more likely to be stopped, arrested, convicted, and given harsher sentences than White Americans who commit the same crimes. Research has also found that White Americans overestimate how much crime is committed by Black and Latinx people, fail to see that communities of color are disproportionately victims of crime, and are more likely to ignore bias in the criminal justice system (Ghandnoosh, 2014). People of color are unable to deny their negative experiences with the criminal justice system.

We can see another example of systemic racism when looking at arrest rates for youth, as youth of color are more likely to be arrested for drug possession than white youth. We often refer to this type of phenomenon as disproportionate minority contact (DMC), which is the disproportionate representation of ethnic, racial, and linguistic minority youth in the juvenile system. Minority youth are overrepresented in every aspect of the justice system. For example, Black youth represent 15 percent of the adolescents in this country but comprise 41 percent of the youth incarcerated in local detention and state correctional facilities, and Latinx youth are incarcerated in local detention and state correctional facilities nearly twice as often as white youth. Research shows that youth of color are treated more harshly than white youth when charged with the same category of offense, including status offenses (2014). If you want to learn more, you can read the report Disproportionate Minority Contact in the Juvenile Justice System in the Chapter Resources.

The criminal justice system has recognized that implicit bias and subconscious beliefs can cause professionals in the field to treat groups unfairly without even realizing they are doing so. For example, they may see one group of people as more violence-prone than another. A study from 2004 found officers paid more attention to Black faces than white faces. Officers who were thinking about crime were more likely to think of people of color. Furthermore, prosecutors are more likely to label crimes committed by Black youth as “aggravated,” whereas equivalent crimes committed by white youth may be presented as “mistakes” (Ojmarrh and MacKenzie, 2004). This is all important when understanding how prejudice can be connected to criminal justice.

White people are more likely to say people of color are arrested at higher rates because an individual officer may be racist, rather than it being a systemic issue, which is a major problem when it comes to discrimination against Black people today. White people are also far less likely to say Black people are treated less fairly than white people in dealing with the police, in the courts, when voting, in the workplace, when applying for a loan or mortgage, and in stores or restaurants (Pew Research Center, 2016a). Our race appears to impact our understanding of prejudice and how it influences our lives.

If white people continue to believe in racial stereotypes, say the scholars who study modern prejudice, they are that much more likely to oppose government efforts to help people of color. For example, white people who hold racial stereotypes are more likely to oppose government programs for African Americans (Quillian, 2006; Krysan, 2000; Sears, Laar, Carrillo, and Kosterman, 1997). Racial prejudice influences other public policy preferences as well. In the area of criminal justice, white people who hold racial stereotypes or hostile feelings toward African Americans are more likely to be afraid of crime, to think that the courts are not harsh enough, to support the death penalty, to want more money spent to fight crime, and to favor excessive use of force by police (Barkan and Cohn, 1998, 2005; Unnever and Cullen, 2010).

In a democracy, it is appropriate for the public to disagree on all sorts of issues, including criminal justice. For example, citizens hold many reasons for either favoring or opposing the death penalty. But it is not appropriate for racial prejudice to be one of the causes. To the extent that elected officials respond to public opinion, as they should in a democracy, and to the extent that public opinion is affected by racial prejudice, then racial prejudice may be influencing government policy on criminal justice and other issues. In a democratic society, it is unacceptable for racial prejudice to have this effect.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=InOsF5x1lZw

Learn More: Philando Castile

Philando Castile was a 32-year-old Black man who was fatally shot by Minnesota law enforcement officer Jeronimo Yanez during a traffic stop in 2016. Castile was in his car with his girlfriend and her 4-year-old daughter when he was pulled over by a police car. The incident occurred in the area near St. Paul, Minnesota, where Castile was stopped for a routine traffic stop. He was then directed by the officer to show his license and ID. However, Philando Castile let Officer Yanez know he had a carrying permit and told him that he was carrying at the time. Officer Yanez still instructed Castile to take out his license, and Castile obliged, reaching down to grab his wallet. During the interaction, Officer Yanez began shooting at the vehicle, fatally killing Castile. Officer Yanez later claimed that he mistook Castille’s actions when he was grabbing his wallet. After the initial shooting, Castile’s girlfriend began to do a Facebook livestream. In the original livestream video, Castile was seen in the front seat, bleeding from his gunshot wounds. Diamond Reynolds, Castile’s girlfriend, was seen in the recording saying that the officer had no reason to shoot and that Castile was only following his instructions. This case surrounded implicit bias and how stereotypes affect Black men in America. Officer Yanez had been made aware that there was a weapon in the vehicle, which Castile made sure to disclose, and it was a legal carry. Castile was legally licensed to carry a gun, and no shots were fired by him during the traffic stop. Castile did not show any signs of hostility and complied with the officer’s every order. However, Officer Yanez felt threatened by Castile and subconsciously believed that Castile was going to shoot. Philando Castile was the victim of police violence and prejudice, and both his girlfriend, Reynolds, and her young daughter will live with trauma from this for life. Philando Castile was declared dead after being taken to the hospital.

Check Your Knowledge

Licenses and Attributions for What is Discrimination?

Open Content, Shared Previously

“What is Discrimination?” is adapted from:

- “Sociology of Race” by Zuleyka Zevallos, The Other Sociologist, licensed with permission under CC BY-NC-SA 4.0.

- “Combating Anti-Black Racism” by Harvard Equity, Diversity, Inclusion, and Belonging, licensed under CC BY 4.0.

Modifications by Shanell Sanchez include remixing, editing for style, and adding U.S. examples.

Figure 2.10. “Changes in Support by Whites for Segregated Housing, 1972–1996” by Thien-Huong Ninh in “2.3.4: Prejudice, SOC 300: Introduction to Sociology (Ninh)” is licensed under an undeclared license and was authored, remixed, and/or curated by LibreTexts. Data from the General Social Survey, 2008.

All Rights Reserved Content

Figure 2.9. “Exhibit on Freedom Riders – Center for Civil and Human Rights – Atlanta – Georgia – USA” by Adam Jones is licensed under CC BY-SA 2.0.

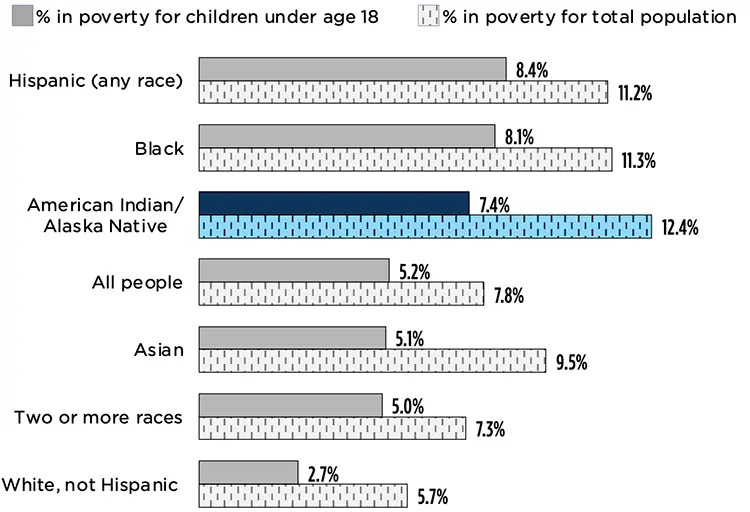

Figure 2.11. “2021 Census estimates show disproportionate poverty among ASIAN children, and the overall ASIAN population” © D. Around Him and H.S.J. Gordon, childtrends.org, is included under fair use.

Figure 2.12. “The racism of the US justice system in 10 charts” by Vox is shared under the Standard YouTube License.

Figure 2.13. Photo of Philando Castile © ACLU Minnesota is included under fair use.

the unfair treatment of marginalized groups, resulting from the implementation of biases, and often reinforced by existing social processes that disadvantage racial minorities

an individual attitude based on inflexible and irrational generalizations about a group of people and literally means “judging before.”

a form of prejudice that refers to a set of negative attitudes, beliefs, and judgments about whole categories of people, and about individual members of those categories because of their perceived race and ethnicity.

a category of people grouped because they share inherited physical characteristics that are identifiable, such as skin color, hair texture, facial features, and stature

shared social, cultural, and historical experiences of people from common national or regional backgrounds that make subgroups of a population different

a formal, codified system of racial apartheid, that prevailed not just in the South but in the entire nation.

simply put, non-urban spaces with lower populations and lots of undeveloped land

widely held beliefs or assumptions about a group of people based on perceived characteristics.

rules a person must follow during probation

refers to how racism is embedded in the fabric of society and how institutional processes are used to maintain systematic discrimination through the complex interactions of large scale societal systems, practices, ideologies, and programs that produce and perpetuate inequities for racial minorities. Also referred to as institutional or structural racism.

a group of people living in a defined geographic area that has a common culture

social research focusing on trends among and between large groups and societies

the type of racism that occurs between individuals, including the beliefs, attitudes, and actions of individuals that support or perpetuate racism. Also called interpersonal racism.

the scientific and systematic study of human relationships, institutions, groups and group interactions, societies, and social interactions, from small and personal groups to large groups

overrepresentation of ethnic, racial, and linguistic minority youth in the juvenile system

automatic and exaggerated mental pictures that we hold about all members of a particular racial group.