3.4 Intergroup Relations and Intergroup Conflict

Intergroup relations are the way people who belong to social groups or categories perceive, think, feel about, and act toward and interact with people in other groups. Intergroup relations can be contentious, often resulting in intergroup conflict. The driving forces are prejudice, racism, and discrimination. Intergroup conflict occurs at all levels of social organization, such as rivalries between gangs, organized disputes, race riots, and international warfare. Groups provide the means to achieve humanity’s most lofty goals, but when groups oppose each other, they are sources of hostility, abuse, and aggression (West Chester University, n.d.). We often see intergroup relationships as a consequence of racialized social control. As a result of the disconnect between racial groups, intergroup relations become increasingly unsympathetic toward each other. Racialized social control results when policies are developed to deter crime and deviance, but disproportionately impact people of color. Ultimately, racialized social control punishes and controls groups because of their race. This form of control can manifest because of the intolerance of a racial group’s actions. The most tolerant form of intergroup relations is pluralism, where people argue that groups of people are of equal standing. At the other end of the continuum are amalgamation, expulsion, and even genocide, which are much less tolerant examples of intolerant intergroup relations. We will discuss these further below. Ethnic and racial groups come into contact through social processes, such as voluntary or involuntary migration, conquest, and expansion of territory. The next section will provide examples of patterns of intergroup relations.

Genocide

Genocide is the deliberate destruction and systematic killing of targeted groups of vulnerable people. Historically, genocide has led to countless murders and detrimental harm to groups of people. The Holocaust (1933–1945) was the systematic, state-sponsored persecution and murder of six million European Jews by the Nazi German regime and its allies and collaborators. The Holocaust era began in January 1933 when Adolf Hitler and the Nazi Party came to power in Germany. It ended in May 1945, when the Allied Powers defeated Nazi Germany in World War II. The Holocaust is also sometimes referred to as “the Shoah,” the Hebrew word for “catastrophe.” The Nazis targeted Jewish people because the Nazis were radically antisemitic. This means that they were prejudiced against and hated Jewish people. Antisemitism was a basic tenet of their ideology and at the foundation of their worldview. The Nazis falsely accused Jews of causing Germany’s social, economic, political, and cultural problems. In particular, they blamed them for Germany’s defeat in World War I (1914–1918). Some Germans were receptive to these Nazi claims. Anger over the loss of the war and the economic and political crises that followed contributed to increasing antisemitism in German society. The instability of Germany under the Weimar Republic (1918–1933), the fear of communism, and the economic shocks of the Great Depression also made many Germans more open to Nazi ideas, including antisemitism (Holocaust Encyclopedia, n.d.). They also targeted Catholic people, people with disabilities, and people within the LGBTQIA+ community. With forced emigration, concentration camps, and mass executions in gas chambers, Hitler’s Nazi regime was responsible for the deaths of 12 million people, 6 million of whom were Jewish. Hitler’s intent was clear, and the high Jewish death toll certainly indicates that Hitler and his regime committed genocide.

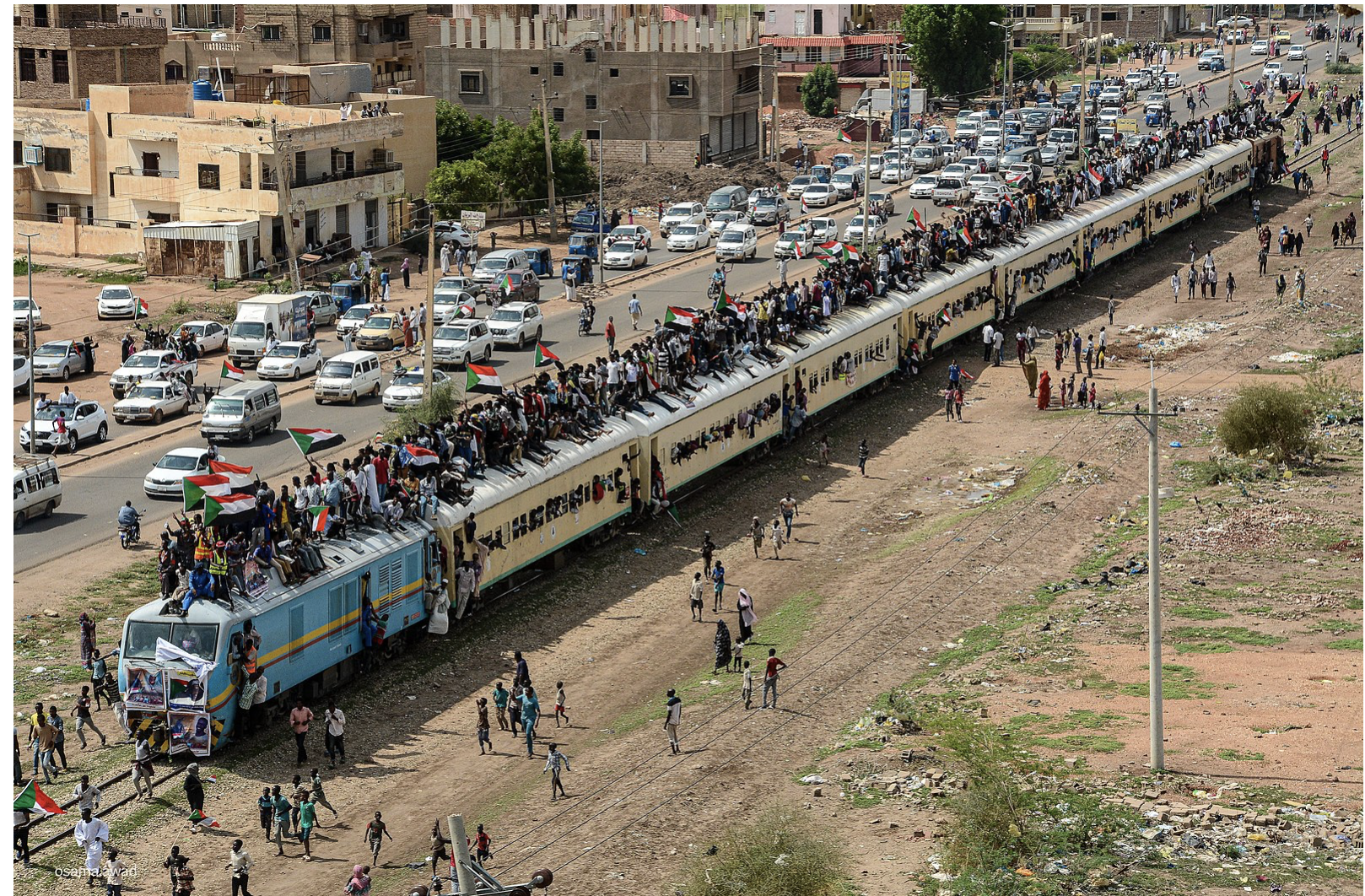

A more recent genocide occurred in 2003 known as the “Darfur Genocide” where approximately 200,000 Fur, Zaghawa, and Masalit people in Darfur, a region in the north of Sudan, by the Sudanese government and their militia, which is known as the Janjaweed (‘Devils on Horseback’) were killed (Bartlett and Akinwotu, 2023). Sudan is the third-largest country in Africa, behind Algeria and Congo. For decades, Sudan’s people have experienced civil war, genocide, drought, theft of the country’s natural resources, and autocratic governments (World Without Genocide, 2023). Sudan is an ethnically diverse country that, at the start of the genocide, was controlled by an Arab dictatorship in the capital of Khartoum. In the years leading up to the genocide, tension in the Darfur region escalated over disputes about land and unequal power, and people in Darfur felt marginalized and ignored by the government, which concentrated its efforts and resources on the capital city and surrounding areas. In 2003, in an attempt to secure more autonomy over their lives, some of the local inhabitants of the Fur, Zaghawa, and Masalit groups in Darfur joined forces to create the Sudan Liberation Army (SLA), which launched an attack on a military airbase in April 2003. The SLA was soon joined by another group known as the Justice and Equality Movement (JEM). In response, the Sudanese government armed and trained local inhabitants in the area to create violent, semiprofessional militias known as the Janjaweed, who were instructed to carry out a series of attacks against Fur, Zaghawa, and Masalit villages. The devastating attacks, which followed on from government bombing of the villages, were intended to diminish any support for the SLA and JEM and secure Fur, Zaghawa, and Masalit lands and resources for the government. Between 2003 and 2005, thousands of villages were destroyed, and their inhabitants were raped, attacked, and murdered. Those that survived the initial attacks were displaced and attempted to survive in the desert (where the government obstructed aid, food, and water supplies) or fled across the border to Chad. In total, over 200,000 people were murdered, and approximately 2.5 million were displaced. Since 2003, the Janjaweed, supported by the government, have continued to target Black Africans in the Darfur region, and this persecution continues today, with approximately 2.7 million people in the area having been displaced. In 2010, the Sudanese president Omar al-Bashir was charged by the International Criminal Court with three counts of genocide. Although a treaty was signed in 2011, the peace is fragile. If you want to learn more about genocide, you can watch the video “Darfur Genocide – PBS” in the Chapter Resources.

Population Transfer or Expulsion

Population transfer or expulsion refers to a subordinate group being forced, by a dominant group, to leave an area or country. As seen in the examples of the Trail of Tears and the Holocaust, expulsion can occur alongside genocide. However, it can also stand on its own as a destructive group interaction. Expulsion has often occurred historically on an ethnic or racial basis. In the United States, President Franklin D. Roosevelt issued Executive Order 9066 in 1942, after the Japanese government attacked Pearl Harbor. The order authorized the establishment of internment camps for anyone with as little as one-eighth Japanese ancestry (i.e., one great-grandparent who was Japanese). The Japanese-American internment camps were makeshift barracks, with families and children cramped together behind barbed wire. Most were U.S. citizens from the West Coast who were forced to abandon or liquidate their businesses when war relocation authorities escorted them to the camps (Qureshi, 2013). Over 120,000 legal Japanese residents and Japanese U.S. citizens, many of them children, were held in camps for up to four years, even though there was never any evidence of collusion or espionage. Many Japanese Americans continued to demonstrate their loyalty to the United States by serving in the U.S. military during the war. In 1988, President Reagan signed the Civil Liberties Act to compensate more than 100,000 people of Japanese descent who were incarcerated in internment camps during World War II. The legislation offered a formal apology and paid out $20,000 in compensation to each surviving victim. The law won congressional approval only after a decade-long campaign by the Japanese-American community (Qureshi, 2013).

Similarly, during the Great Depression from 1929 to 1936, there was an emergence of anti-Mexican sentiment as white Americans began to lose their employment. Up to 1.8 million people of Mexican descent – most of them American-born – were rounded up in informal raids and deported to reserve jobs for white people. In the 1930s, the Los Angeles Welfare Department deported hospital patients of Mexican descent. These deportations happened in border states like California and Texas, but also in places like Michigan, Colorado, Illinois, Ohio, and New York. Dunn (2004) estimates that around 60 percent of these people were American citizens, many of them born in the United States to first-generation immigrants. For these citizens, deportation wasn’t “repatriation” – it was exile from their country. As with other examples of xenophobia and nativism, the growing resentment led to changes in official immigration policies. According to Aguirre and Turne (2007), a repatriation movement was initiated, and over half a million people of Mexican origin (including both migrants and U.S.-born) were repatriated to Mexico between 1929 and 1935 (Little, 2019).

Internal Colonialism

Internal colonialism occurs when members of a racial or ethnic group are conquered or colonized and forcibly placed under the economic and political control of the dominant group within a country or internally. Typically, the dominant group controls and manipulates important social institutions to suppress and deny full access to societal benefits for all people. The 1830 Indian Removal Act called for the relocation of Indigenous people to land west of the Mississippi. Another example is the European colonization of North America. European settlers coerced and forced Indigenous people off their lands, often causing thousands of deaths in forced removals, such as occurred in the Cherokee or Potawatomi Trail of Tears. Settlers also enslaved Native Americans and forced them to give up their religious and cultural practices. In the 1600s and 1700s, British forces tried to drive out Native Americans by cutting down their corn and burning their homes, turning them into refugees (Kiger, 2023). There were also concerns that the introduction of European diseases and Native Americans’ lack of immunity to them contributed to massive deaths. Smallpox, diphtheria, and measles flourished among Indigenous Tribes who had no exposure to the diseases and no ability to fight them. Quite simply, these diseases decimated the Tribes. How planned this genocide was remains a topic of contention, and it’s also not clear whether or not the attempt at biological warfare had the intended effect. Colonial weaponizing of smallpox against Native Americans was first reported by 19th-century historian Francis Parkman. Parkman came across correspondence in which Sir Jeffery Amherst, commander in chief of the British forces in North America in the early 1760s, discussed its use with Col. Henry Bouquet, a subordinate on the western frontier during the French and Indian War. However, there’s only one documented instance of a colonial attempt to spread smallpox during the war, and oddly, Amherst probably didn’t have anything to do with it. There’s also no clear historical verdict on whether the biological attack even worked. Even if it didn’t work, British officers intended to kill women and children, as well as warriors (Fenn, 2001; Kiger, 2023; Lewy, 2004).

In the United States, slavery is considered an extreme example of internal colonialism. Other examples include the South African system of apartheid and the abusive use of immigrant labor in the United States, such as the Bracero Program, a guest worker program that was in place from 1942 to 1964. The program, officially referred to as the Mexican Farm Labor Program, was initiated through an executive order in 1942 and was intended to bring in Mexican workers to fill expected labor shortages in the agricultural sector. Although there were protections and limits written into the bilateral agreement, employers largely ignored the rules, and Mexican laborers typically worked under harsh conditions, and many were not paid standard wages (Gutierrez and Almaguer, 2016). Internal colonialism is typically accompanied by segregation, which allows the majority group to maintain social distance from the minority and yet economically exploit their labor as agricultural workers, cooks, janitors, nannies, or factory workers.

Segregation: De Facto and De Jure

Segregation, from a legal lens, is the practice of requiring separate housing, education, and other services for people of color. It is important to distinguish between de jure and de facto segregation. De jure segregation is a legally enforced separation, and de facto segregation occurs without law enforcement, but because of other factors. A stark example of de jure segregation is the apartheid movement in South Africa, which existed from 1948 to 1994. Under apartheid, Black South Africans were stripped of their civil rights and forcibly relocated to areas that segregated them physically from their white compatriots. Only after decades of degradation, violent uprisings, and international advocacy was apartheid finally abolished.

De jure segregation occurred in the United States for many years after the Civil War. During this time, many former Confederate states passed Jim Crow laws that required segregated facilities for Black people and white people. These laws were codified in 1896’s landmark U.S. Supreme Court case Plessy v. Ferguson, which stated that “separate but equal” facilities were constitutional. For the next five decades, Black people were subjected to legalized discrimination and forced to live, work, and go to school in separate – but unequal – facilities. It wasn’t until 1954 and the Brown v. Board of Education case that the U.S. Supreme Court declared that “separate educational facilities are inherently unequal,” ending de jure segregation in the United States.

De facto segregation, however, does not just dissipate because of court mandates. Segregation is still alive and well in the United States, with different racial or ethnic groups often segregated by neighborhood, borough, or parish. Sociologists use segregation indices to measure the racial segregation of different races in different areas. The indices employ a scale from zero to 100, where zero is the most integrated and 100 is the least. In the New York metropolitan area, for instance, the Black-white segregation index was 79 for the years 2005 through 2009. This means that 79 percent of either Black or white people would have to move for each neighborhood to have the same racial balance as the whole metro region (Population Studies Center, 2010).

Cultural Assimilation

Cultural assimilation, initially referred to as assimilation, was defined as the economic, social, and political integration of an ethnic minority group into mainstream society (Keefe and Padilla, 1987). People are often encouraged or pressured to culturally assimilate, but these changes are often forced. Indigenous, immigrant, and other groups often change or hide elements of their own culture, including their language, food, clothing, and spiritual practices, to adopt the values and social behaviors of the dominant culture (Seven, 2023). One example of forced cultural assimilation that was forced through racialized social control was when Native American children were forced to go to boarding schools. Beginning with the Indian Civilization Act Fund of March 3, 1819, and the Peace Policy of 1869, the United States, in concert with and at the urging of several denominations of Christianity, adopted an Indian Boarding School Policy. The slogan “Kill the Indian, Save the Man.” There were more than 523 government-funded, and often church-run, Native American boarding schools in the United States in the 19th and 20th centuries. Native children were taken by government agents from their homes, sent to schools hundreds of miles away, beaten, starved, and forced to stop speaking their native languages. By 1926, nearly 83% of Native children were attending boarding schools. The program was intentionally designed by the government to save the government money, force assimilation, and eradicate Native cultures (Adams, 1995; Healing Voices, 2020; National Native American Boarding School Healing Coalition, 2023). Historically, the cultural assimilation model emphasized conformity with white American cultural values, practices, holidays, and the exclusive use of the English language and promoted the subordination of ethnic and immigrant cultural values. This model also influenced important legislation such as the Immigration National Origins Act of 1924 (also called the Johnson-Reed Act), which favored European immigration at the expense of non-European countries and specifically excluded Asian countries from immigration. To learn more about the U.S. program to force assimilation for Indigenous children, read the article “U.S. Funded 400 Schools to Assimilate Indigenous Children” in the Chapter Resources.

Activity: The Social Impact of Textbooks and Curriculum

On August 13, 2001, 20 South Korean men gathered in Seoul. Each chopped off one of his fingers because of textbooks. These men took drastic measures to protest eight middle school textbooks approved by Tokyo for use in Japanese middle schools. According to the Korean government (and other East Asian nations), the textbooks glossed over negative events in Japan’s history at the expense of other Asian countries (The Telegraph, 2001).

In the early 1900s, Japan was one of Asia’s more aggressive nations. Korea was held as a colony by the Japanese between 1910 and 1945. Today, Koreans argue that the Japanese are whitewashing their colonial history through these textbooks. One major criticism is that they do not mention that, during World War II, the Japanese forced Korean women into sexual slavery. The textbooks describe the women as having been “drafted” to work, a euphemism that downplays the brutality of what occurred. Some Japanese textbooks dismiss an important Korean independence demonstration in 1919 as a “riot.” In reality, Japanese soldiers attacked peaceful demonstrators, leaving roughly 6,000 dead and 15,000 wounded (Crampton, 2002). Although it may seem extreme that people are so enraged about how events are described in a textbook that they would resort to dismemberment, the protest affirms that textbooks are a significant tool of socialization in state-run education systems.

What modern parallel examples have you seen in the United States? How important are textbooks in educating a society? How might the removal of information about intergroup relations and conflicts further perpetuate harm?

Check Your Knowledge

Licenses and Attributions for Intergroup Relations and Intergroup Conflict

Open Content, Shared Previously

“Intergroup Relations and Intergroup Conflict” is adapted from “Racial Tension in the United States” by Lumen Learning, Introduction to Sociology, which is licensed under CC BY-SA 4.0. Modifications by Shanell Sanchez and Catherine Venegas-Garcia, revised by Jessica René Peterson, licensed CC BY-SA 4.0, include rewording and elaborating.

“Activity: The Social Impact of Textbooks and Curriculum” is adapted from “5.3 Agents of Socialization” by Tonja R. Conerly, Kathleen Holmes, and Asha Lal Tamang, Introduction to Sociology 3e, OpenStax, which is licensed under CC BY 4.0. Modifications by Shanell Sanchez and Catherine Venegas-Garcia, revised by Jessica René Peterson, licensed under CC BY 4.0, include updating for currency and adding discussion questions.

Figure 3.7. “Sudanese revolution: The River Nile State _ Sudan” by Osama Elfaki is licensed under CC BY-SA 4.0.

Figure 3.8. “Russell Lee: Japanese-American family waiting for relocation, Los Angeles, 1942” by trialsanderrors is licensed under CC BY 2.0.

Figure 3.9. “Trail of Tears for the Creek People” by TradingCardsNPS is licensed under CC BY 2.0.

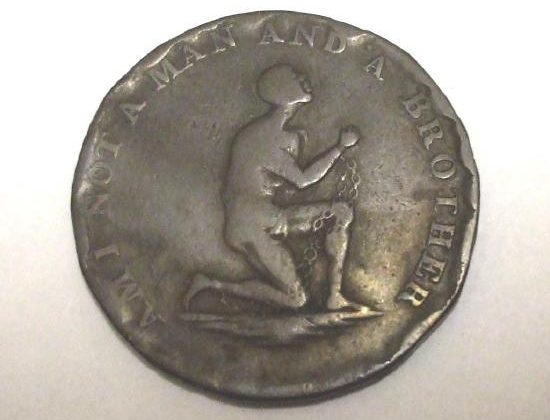

Figure 3.10. “LEEDM.N.1970.34.1 obv” by Leeds Museums and Galleries is licensed under CC BY-NC 2.0.

Figure 3.11. “Beale Street, Memphis, Tennessee” by Marion Post Wolcott is in the Public Domain, courtesy of the Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division, Farm Security Administration/Office of War Information Black-and-White Negatives.

Figure 3.12. The photo of Kenneth and Mamie Clark is in the Public Domain.

Figure 3.13. “Liberty-statue-from-below cropped” by Derek Jensen (Tysto) is in the Public Domain, CC0 1.0.

Figure 3.14. “Sugar-coated donut” by BrokenSphere is licensed under CC BY-SA 3.0.

the way people who belong to social groups or categories perceive, think about, feel about, and act towards and interact with people in other groups.

occurs at all levels of social organization such as rivalries between gangs, organized disputes, race riots, and international warfare.

an individual attitude based on inflexible and irrational generalizations about a group of people and literally means “judging before.”

a form of prejudice that refers to a set of negative attitudes, beliefs, and judgments about whole categories of people, and about individual members of those categories because of their perceived race and ethnicity.

the unfair treatment of marginalized groups, resulting from the implementation of biases, and often reinforced by existing social processes that disadvantage racial minorities

a category of people grouped because they share inherited physical characteristics that are identifiable, such as skin color, hair texture, facial features, and stature

organized action intended to change people’s behavior (Innes 2003).

the enactment of specific policies to deter deviousness that disproportionately impacts people of color (Patel, 2018).

the deliberate destruction and systematic killing of targeted groups of vulnerable people

a group of people living in a defined geographic area that has a common culture

occurs when members of a racial or ethnic group are conquered or colonized and forcibly placed under the economic and political control of the dominant group within a country or internally

rules a person must follow during probation

the economic, social and political integration of an ethnic minority group into mainstream society (Keefe & Padilla, 1987). Initially referred to as assimilation.

a group’s shared practices, values, and beliefs.

the process through which people are taught to be proficient members of a society.