3.5 Modern-Day Racialized Social Control

When Franklin D. Roosevelt was elected as president in 1933, he brought the United States a new form of social control. President Roosevelt, along with Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) Director J. Edgar Hoover and Attorney General Homer Cummings, continued the War on Crime campaign to rally the nation against criminals (Denney, 2021). The War on Crime was meant to reduce crime and criminal behaviors, but these policies were enforced more frequently in Black and Brown communities. Roosevelt’s administration was during a time of economic depression, which meant that crime and poverty were increasing along with the unemployment rate. To combat the economic crisis, President Roosevelt worked on the implementation of the New Deal agenda (Cooper, 2017). While the New Deal’s focus was on the economic crisis at the time, it heavily aided in the development of our modern-day criminal justice system. The War on Crime helped double the FBI’s budget and its employment numbers. By 1939, the federal prison population had increased by 66 percent (Denney, 2021). Supermax prisons, military-type policing tactics, and new legislation were enacted thanks to the War on Crime. Black inequalities and lynchings were ignored by Roosevelt, Hoover, and Cummings during this period. This agenda targeted Black communities, leading to an increase in Black prison populations.

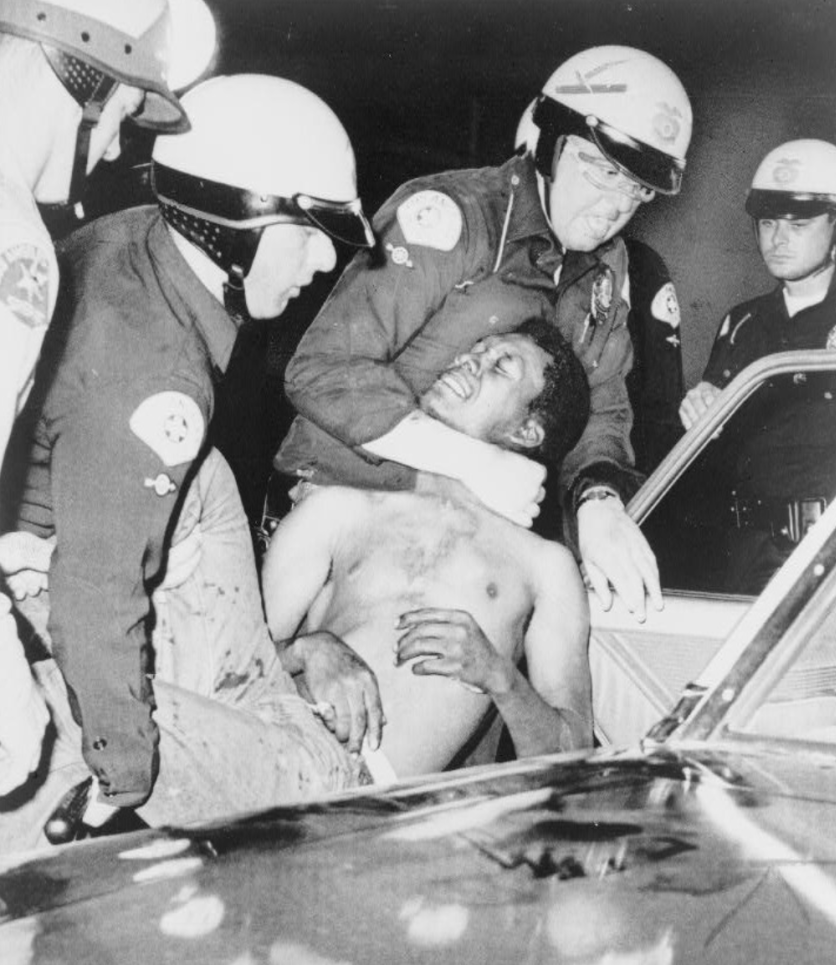

Housing insecurity, poor education resources, and loss of jobs gave way to a crime wave in 1960s New York. Black communities often faced the brunt of these issues, and they also faced racial discrimination and violence from police officers. With the social conditions in Harlem, Black communities grew more frustrated (Flamm, 2015). Civil Rights activists organized peaceful protests to highlight the violence that Black communities faced at the time. However, these protests grew violent as racial tensions grew. Police responded to the Harlem Riot of 1964 with violence, and they beat the peaceful protesters. As a result, hundreds of individuals were wounded and arrested, while many businesses had to shut down due to looting. In 1964, the link between race and criminality rose as politicians Lyndon Johnson and Barry Goldwater fought for the presidency. Both politicians acknowledged that tensions were high as crime rates rose in New York (Hinton, 2015a). Reducing street crime was one of the election promises in Goldwater’s political campaign. In an attempt to increase voter support, Johnson announced that he would start a “War on Crime,” which looked to reduce the crime rates at that time. Because of the increasing riots and student protests, Johnson increased funds for police departments through the Law Enforcement Assistance Administration initiative. Further militarizing them, police officers were also given bulletproof vests, rifles, tanks, and gas masks to aid in controlling racial uprisings (Hinton, 2015b). The War on Crime would have disastrous effects in the future, as Black communities became targets of policing hot spots and policies that took a tough stance on crime. See Chapter 5 for more information on the police role in the War on Crime and the War on Drugs.

Learn More: Watts Rebellion or Watts Riot and the National Guard

The Watts Rebellion, also known as the Watts Riots, was a large series of riots that broke out on August 11, 1965, in the predominantly Black neighborhood of Watts in Los Angeles. The Watts Rebellion lasted for six days, resulting in 34 deaths, 1,032 injuries, and 4,000 arrests, involving 34,000 people and ending in the destruction of 1,000 buildings, totaling $40 million in damages (Hinton, 2023; History, 2020), which marked a turning point for support for the War on Crime. This was considered one of the most violent and deadly encounters between police and over 35,000 civilians in American history. The Watts Riots came in response to police brutality in communities with high rates of poverty and people of color. Media coverage of the uprising fed into stereotypical fears about Black people, claiming they were disobedient, criminal, violent, and ungovernable. Black youth were portrayed as “Public Enemy No. 1,” and this reinforced the belief that they must be brought under social control. The government brought in the National Guard, which at that time was considered unheard of in American society. We have recently seen this with the Black Lives Matter protests under the former Trump administration and the U.S. government (Baldor, 2021). This connects to the modern day, because former President Trump has been campaigning in 2023, saying he will use the military to quell violence in primarily Democratic cities and states if re-elected. Calling New York City and Chicago “crime dens,” the front-runner for the 2024 Republican presidential nomination told his audience, “The next time, I’m not waiting. One of the things I did was let them run it, and we’re going to show how bad a job they do,” he said. “Well, we did that. We don’t have to wait any longer” (PBS, 2023).

If you want to learn more about this, read the article “Black National Guard Members Express Discomfort with Quelling Black Lives Matter Protesters” in the Chapter Resources.

Black Panther Party

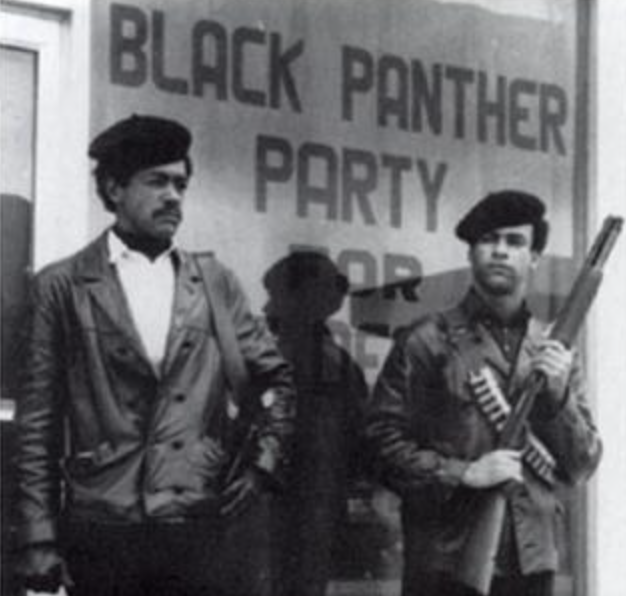

Originally established in California, one of the early focuses of the Black Panther Party was to observe police activity within Black communities and protect against attacks (History, 2023). After more Black communities were being terrorized by police brutality, Black college students Huey P. Newton and Bobby Seale founded the Black Panther Party for Self-Defense in 1966. As the Black Panthers became more popular, Newton and Seale expanded the Black Panther Party’s goals to get more Black officials elected to political positions. These efforts worked to diversify the political parties back then, allowing for Black voices to be heard. The Black Panther Party also fought to bring lower-income Black communities together by providing resources. They helped create over 35 “survival” programs and expanded to various cities across the United States. Some of the programs they created included free dental care, free clothes and shoes, free ambulance services, employment referral services, community food pantries, free gynecologist services, WIC programs, The Black Panther newspaper, a foundation for sickle cell anemia research, police patrols, legal aid assistance, GED classes, and free pest control services (Intersectional Black Panther Party History Project, n.d.). One of the most progressive and lasting programs they constructed was the Black Panthers’ Free Breakfast for School Children program. Hundreds of children were fed healthy meals because of this program. Teachers also found that kids participating in the program started doing better in school (History, 2021). Before that, many of them were forced to go hungry until lunchtime came around. Eventually, FBI Director J. Edgar Hoover called for police departments to dismantle the Black Panther Party’s free breakfast program. Police officers would go into schools and harass Black Panther Party members in front of participating students. To discourage parents from allowing their children to join, they would go to their houses and lie about the food, causing illnesses. It got to the point where they would go and urinate on the food before it could be eaten (History, 2021). Eventually, these efforts helped break up the Black Panthers’ free breakfast program. After the backlash from many people, the federal government would go on to create its widespread breakfast program.

We can trace back some of the earlier methods of racialized social control to the Black Panther Party organization. Because of their increasing influence among the Black community, the FBI viewed the Black Panther Party as an enemy of the U.S. government and sought to dismantle the party. In 1967, the FBI quietly unleashed a covert surveillance operation targeting civil rights groups and Black leaders, including the Black Panther Party, Martin Luther King Jr., Elijah Muhammad, Malcolm X, and many others. The counterintelligence program (COINTELPRO) objective was to “expose, disrupt, misdirect, discredit, or otherwise neutralize” the radical fight for Black rights – and Black power (Hoban, 2021). These efforts were extremely violent, working to induce fear into the Black Panthers and discourage them from helping Black communities gain social equality (Hoban, 2021). The FBI carried out a secret, nationwide effort to “destroy” the Black Panthers, including attempts to stir bloody “gang warfare” between the Panthers by creating internal tension. For example, a note was sent to the leader of the street gang, Jeff For, saying, “There’s supposed to be a hit out for you” (Kifner, 1976). The Panthers were the primary focus of the “Black nationalist hate groups” section of COINTELPRO by July 1969 and were the target of 233 of the 295 actions authorized against Black groups (Kifner, 1976). The bureau’s efforts, part of the COINTELPRO or counterintelligence program, contributed to a climate of violence in which four Black Panthers were shot to death, the report says. The Black Panthers were victims of the racialized social control that the FBI utilized to disband them. Unfortunately, multiple members were either wounded, arrested, or executed by the FBI. Violence faced by the Black Panther Party from police officers and FBI agents weakened the organization, and it would officially disband in 1982 (History, 2023). Because of their race and power, the Black Panther Party was targeted using methods of social control.

Learn More: The Legacies of Fred Hampton and Mark Clark

Fred Hampton was the 21-year-old Black chairman of the Black Panther Party in Chicago, Illinois. He was charismatic and a gifted student. A member of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People and a leader of the West Suburban Branch’s Youth Council, his work was revolutionary in the advancement of socialism. Hampton helped ally with the Puerto Rican group named The Young Lords and the white group called The Young Patriots. These groups united and formed the Rainbow Coalition, which aimed to create social change for their communities.

As a member of the Black Panther Party, Fred worked hard to bring justice to the Black victims of violence from the government. The revolution he led united different racial groups, all sought equality for their people. With the unification of these groups, the power they had helped shine light on the inequalities they faced. As Fred spoke out about the injustice Black communities faced, the government – including the FBI, Cook County State Attorney’s Office, and the Chicago Police Department – began to see him as an immediate threat. On December 4, 1969, Fred was shot and killed by raiding police officers while sleeping next to his pregnant fiancée.

Mark Clark was a 22-year-old Black man living in Peoria, Illinois. He was a member of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People in his youth. When he grew older, he joined the Black Panther Party. As a member of the Black Panther Party, he frequently recruited others to join and expand the program. Mark helped establish the Free Breakfast Program in Peoria, Illinois. He was also a Defense Captain for the Peoria Branch of the Black Panther Party and joined Fred Hampton the night they were raided. Mark was sitting in a chair near the entrance of the apartment building when police shot and killed him.

On the night of the raid, Chicago police officers shot over 90 times. While Mark and Fred died, another four members were wounded in the attack. Fred Hampton’s murder was covered up and made out to be part of a mutual shootout between the Black Panthers and the Chicago Police. However, it was found that the Black Panthers did not fight back. Instead, Fred was drugged and caught blindsided by the raid.

The Black Panther Party was heavily attacked by the government, and as a result, many of the group’s members were either arrested or assassinated to weaken their influence. To fight the efforts of the Black Panthers, the FBI worked to reduce the effects of their social programs. They made it significantly harder for members to host community events by frequently sabotaging them. Multiple members were targeted due to their association with the Black Panthers. In cities like Los Angeles, Chicago, and Detroit, Black Panther Party members were arrested and attacked (Lassiter, 2021). The FBI frequently gave false information to obtain warrants, and without a doubt, they did everything in their power to control the Black Panther Party.

The FBI and various police departments enforced racialized social control upon the Black Panthers. All of the arrests made, the murders of over 29 members, and the raids were done to fully get rid of the Black Panther Party. Despite all this, they continued to persist. The Black Panther Party began as a response to the police brutality cases seen in Black neighborhoods. Through their power and influence, they fought hard to bring racial justice. Their outreach greatly helped these communities, but unfortunately, it also made them prime targets for racist ideologies from the government. In the end, they simply could not win against the FBI’s power and weapons.

If you want to learn more, you can watch the video “Why the U.S. Government Murdered Fred Hampton – Vox” in the Chapter Resources.

Gun Control

The ramifications of racialized social control are often still in effect today. Some of the gun control laws we see in current times arose as an attack on the Black Panther Party’s liberty and their display of the Second Amendment, which is the right to bear arms. In response to the increasing police brutality against Black communities, the Black Panther Party created its own police force. Displaying a more militant approach, this police force was designed to protect Black neighborhoods from the police. Members of the Black Panther Party would patrol the streets, visibly armed with shotguns, rifles, and handguns (History, 2018). California’s gun laws at the time allowed residents to carry guns as long as they weren’t prohibited due to lax gun laws (Morgan, 2018). Soon, more members of the Black Panther Party began arming themselves during protests, and politicians grew fearful of their power.

Republican Assembly member Ron Mulford drafted AB 1591, which made it a felony to openly carry any guns in public (SFGATE, 2000). After a 1967 protest regarding the Mulford Act, where 30 armed Black Panther Party members took to the California State Courthouse, legislators worked to pass the bill faster (History, 2018). Soon, California State Governor Ronald Reagan quickly signed and passed the 1967 Mulford Act. This act was created to deter the Black Panther Party from displaying guns (Aiken, 2022). For the first time in history, gun control regulations were passed, but they were only created to disarm the Black Panthers. Even after decades have passed, the state of California has some of the strictest gun control laws in the United States (Vankin, 2022).

In more contemporary times, we see how white groups use guns without the same regulations as Black and Brown groups. Despite the massive gun violence issue and mass shootings in America, nothing has incited the same fear within politicians to act as the armed Black Panther members once did. Bans on assault rifles and other forms of regulations have been named “unconstitutional,” and many measures drafted to reduce gun violence have met resistance from anti-gun control groups (ABC News, 2023). Even now, we have seen the usage of guns as a form of protest without any repercussions. On January 6, 2021, thousands of President Donald Trump’s supporters stormed the United States Capitol in Washington, D.C., to protest his 2020 election loss (History, 2022). The treatment between the Black Panther Party and the January 6th Capitol rioters differed vastly. Both the January 6th riot and the 1967 Black Panther protest were labeled as “invasions” by news outlets, even though the Capitol attack was much more violent. During the Black Panther Party protest, members were arrested despite not violating any constitutional laws. However, even though there was violence arose during the January 6th Capitol riot, no such laws were introduced. These two groups were treated differently. Had the members of the January 6th Capitol riot been Black, the ending would have played out differently. Racialized social control affects Black and Brown individuals in harsher ways than white individuals. As a result of the Black Panthers’ peaceful protest, gun control was enacted into legislation. The introduction of gun control laws after the protest was a form of control that aimed to manage the actions that the Black Panther Party could and could not do. It criminalized their protests, thus allowing them to be more easily imprisoned and contained.

Mass Incarceration

Trappen says from the sociological perspective, mass incarceration – referring to the overwhelming size and scale of the U.S. prison population – allows us to shift from thinking about prison as merely a place where we warehouse lawbreakers, but as a structural system of social control. Trappen reminds us that in making this conceptual shift, we begin to get a better understanding of what prisons are, how they function, and how they are essentially “made” in our contemporary moment. “Slavery in the U.S. context was, among other things, a system of racialized social control that was predicated on the notion of providing free labor for wealthy white landowners, who were, for the most part, located in the American South” (Trappen, 2018). We see that states that supported slavery also have the highest rates of mass incarceration of people of color today.

Mass incarceration has become so normalized in the American criminal justice system that unless you know someone who has been incarcerated, you probably don’t think much about it. Which is to say, it is not likely that you’ve paused long enough to think critically about how locking up so many people has become effectively normalized in the United States, to the extent that it shapes almost everything about how you and many others perceive “what is a crime,” “who is criminal,” “who is a citizen,” “who deserves rights,” and so on down the line.… The term “mass incarceration” only scratches the surface. On the one hand, prisons are structures, like warehouses. More to the point, as critics have pointed out, they constitute a massive system of social control that is highly racialized, given how it primarily incarcerates disproportionate numbers of people of color (Trappen, 2018).

Mass incarceration occurs because of policy changes that lead to massive arrests of people. The United States locks people up for small crimes, referred to as the “massive misdemeanor system” in the United States, which contributes to overcriminalization and mass incarceration (Sawyer and Wagner, 2023). For behaviors as benign as jaywalking or sitting on a sidewalk, research estimates 13 million misdemeanor charges have led Americans into the criminal justice system each year (and that’s excluding civil violations and speeding). Low-level offenses typically account for about 25 percent of the daily jail population nationally, and much more in some states and counties (Natapoff, 2018; Sawyer and Wagner, 2023). Anytime people are caught up in the criminal justice system, the effects will be felt financially, personally, and socially. People charged with misdemeanors are often not appointed counsel and are pressured to plead guilty and accept a probation sentence to avoid jail time (Iannelli, 2019).

Mass incarceration saw exponential rates during Richard Nixon’s presidency with the War on Drugs campaign (Taifa, 2021), as you will read more about in Chapter 9. During Bill Clinton’s presidency, Tough on Crime rhetoric enforced harsher punishments within the criminal justice system. As police disrupted Black communities, prison populations skyrocketed. Early prison populations saw an increase from the 1970s, which had around 300,000 incarcerated individuals (Pfaff, 2015). Now, prison populations are made up of around 2.2 million people (Vera Institute of Justice, n.d.). Racialized social control in early U.S. history helped imprison Black and Brown individuals at higher rates. In more contemporary times, police departments and legislative policies still target Black and Brown individuals more than any other race.

Within the United States, Black individuals saw the highest jail incarceration rates in the year 2021. Out of every 100,000 incarcerated residents, 528 of them were Black. There were 316 incarcerated American Indians/Alaska Natives, 157 white individuals, 145 Latinx/Hispanics, and 110 Native Hawaiians/other Pacific Islanders per 100,000 of the population (U.S. Bureau of Justice Statistics, 2022). Within prisons, Black and white inmates have similar rates of death row sentences. There were 1,023 white inmates on death row in the year 2022, closely followed by 986 Black inmates on death row (Legal Defense Fund, 2022). As seen through the prison populations, Black individuals are being incarcerated at higher rates despite making up only 13 percent of the U.S. population (World Population Review, 2023). What we are seeing is that Black and Brown individuals are being overrepresented within jails and prisons. They are also receiving more death row sentences relative to their population size. Outside of prison and jail, Black populations have higher rates of dying by police shootings (Washington Post, 2023). This fatality rate was much higher than other ethnicities or races. If you want to learn more about the use of mass incarceration as a tool of social control, watch the Michelle Alexander video in the Chapter Resources.

Learn More: Private Prisons and Incarceration of Latinx Immigrants

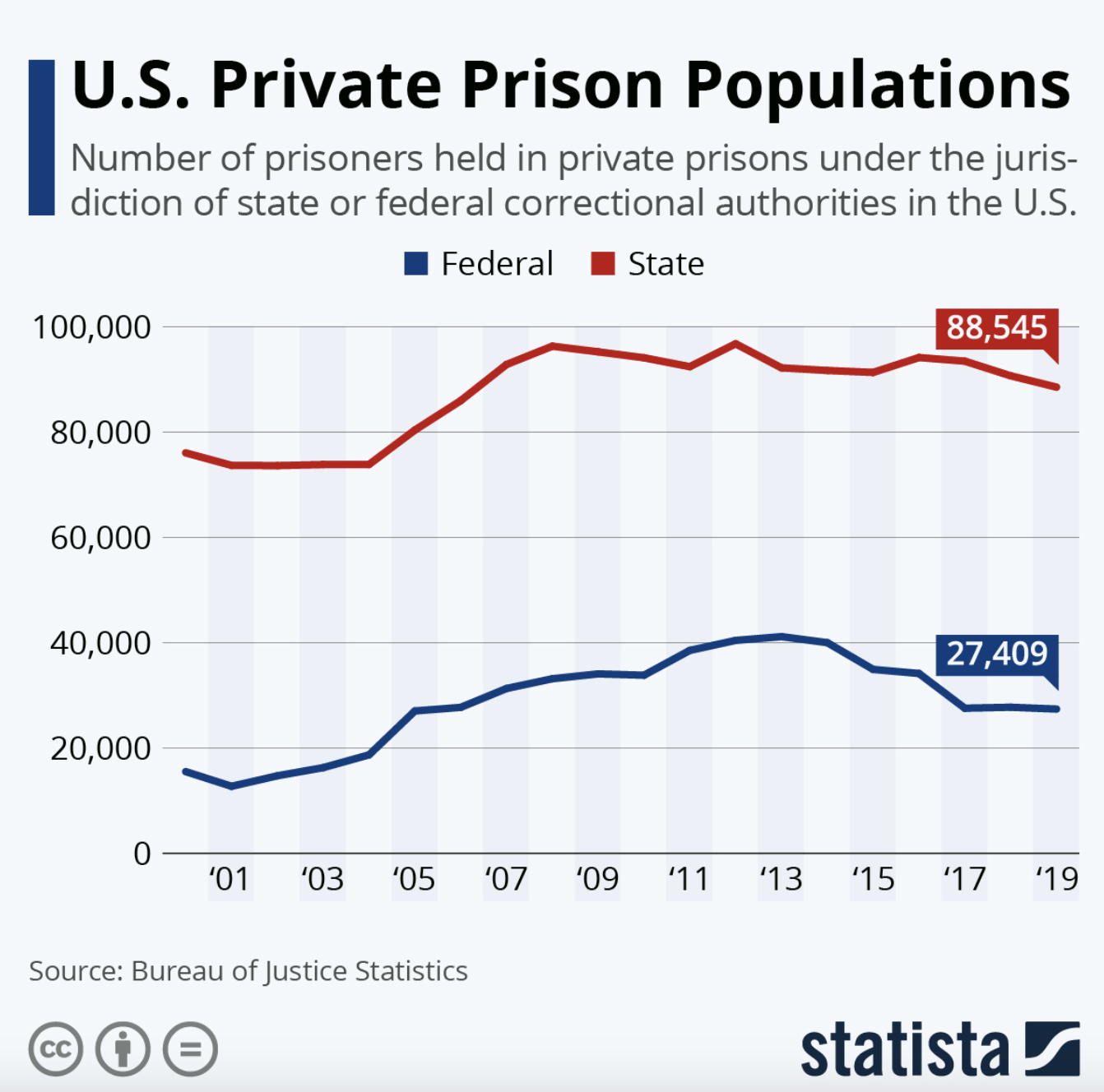

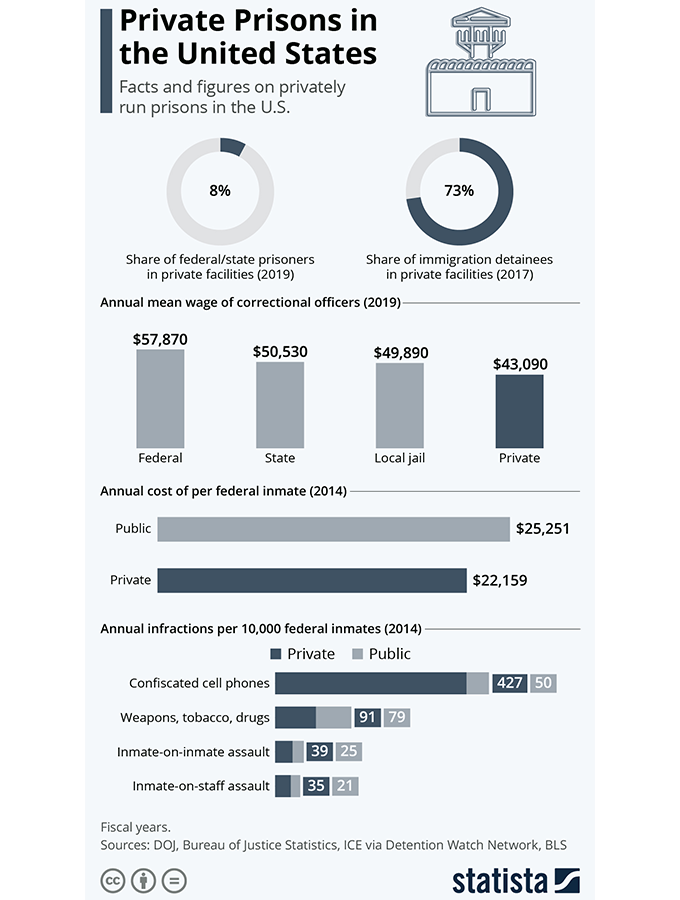

Private prisons run on a for-profit business plan and gain monetary profit by housing inmates within their facilities. State prisons often suffer from overcrowding, so private prisons charge a fee to house inmates. Many of these prisons seek to get as many prisoners as possible, leading to overcrowding and other issues. Because of this, health concerns, lack of resources, inedible meals, and fewer support staff are all common in private prisons. In addition to alleviating state prison overloads to increase profit, private prisons heavily rely on imprisoning undocumented Latinx immigrants as well. Mass incarceration is one of the forms of social control against Latinx individuals, stemming from the fears of immigrants and perceived criminal behavior. Around 73 percent of those located in private prisons are immigrant detainees, and a large majority of them are detained after crossing the border (Cho, 2021). Inside private prisons, undocumented immigrants are arrested and sent to these facilities while they await their trials.

Inside these facilities, many of the inmates live in inhumane conditions. Migrants are beaten, pepper-sprayed, and are not given adequate medical treatment. Around 12,000 migrant children were also held in detention centers, and they faced the same brutalities as incarcerated adults. Intergroup relations would explain this hostility as a result of conflict between groups because of their ethnicity and legal status. Additionally, many of the policies regarding Latinx individuals look at citizenship status, targeting and imprisoning undocumented immigrants over other groups. Because of their legal status, undocumented immigrants don’t have the same legal rights as other citizens, leaving them vulnerable to mistreatment and abuse. In the end, private prisons take advantage of Latinx immigrants to maximize their profits, fusing the criminal justice system and corporations into one major organization. Undocumented immigrants are often overlooked in the criminal justice system, so it is easier to target this group to fund private prisons. Despite the violence that undocumented immigrant adults and children face inside these detention centers, this news is largely ignored.

If you want to learn more about private prisons, see the New York Times article in the Chapter Resources.

New Jim Crow

New Jim Crow laws refer to recent legislation created to enforce social control on Black people and communities of color. Michelle Alexander, the author of The New Jim Crow (2014), is a civil rights advocate, lawyer, legal scholar, and professor. In her book, she shows how mass incarceration is a system of racial and social control, as discussed above. Alexander states that mass incarceration is an excellent example of racialized social control because it “is the process by which people are swept into the criminal justice system, branded criminals and felons, locked up for longer periods than most other countries in the world who incarcerate people who have been convicted of crimes, and then released into a permanent second-class status in which they are stripped of basic civil and human rights, like the right to vote, the right to serve on juries, and the right to be free of legal discrimination in employment, housing, [and] access to public benefits” (Alexander, 2014).

Criminal profiling, generally, as practiced by police, is the reliance on a group of characteristics they believe to be associated with crime. Profiling has also become a major problem within the criminal justice system. Policies painted Black people as criminals and looked to control them from participating in devious behaviors (Remnick, 2020). Drug criminalization, Stop and Frisk, and forced prison labor – all of which will be discussed in future chapters – are all examples of such policies. Among these policies, New Jim Crow laws treat mass incarceration as a means to target Black communities, more specifically, young Black men. In cities with a larger Black population, places with more employed police officers saw a 70 percent increase in low-level arrests of Black individuals (Barlow, 2020). Within our court systems, Black men are 20 percent more likely than white men to receive longer sentences despite having committed the same crime (Wiley, 2022). Another issue is that Black people are twice as likely to be charged with a mandatory sentence offense compared to their white counterparts. As a result, they are forced into jail for much longer. Consequently, methods of social control target Black people at higher rates than other racial and ethnic minorities.

Juan Crow Laws

Similar to the New Jim Crow laws, the Latinx community faces racialized social control laws through Juan Crow laws, a series of immigration policies that disproportionately affect Latinx communities through racial profiling. Forms of social control regarding Latinx people primarily focus on immigration policies. These policies are created to target undocumented Latinx immigrants, but they end up harming American citizens as well due to racial profiling. Under the pretext of deporting individuals who were undocumented, legislation such as Arizona’s SB 1070 heavily encouraged police officers to discriminate against Latinx people. Under SB 1070, border patrol officers could now stop anyone deemed “suspicious” of being undocumented (ACLU, n.d.). Citizens were also required, as stated in SB 1070, to carry full documentation of their legal status, despite it not being under federal law requirement. Failure to show your papers would allow officers to detain individuals until their legal status could be confirmed. In other states, policies like SB 1070 were enacted, and despite federal legislation demanding they stop enforcing it, officers continued for years. Alabama legislation followed a similar route to Arizona by creating HB 56. HB 56 allowed officers to stop individuals on suspicion of legal status. All of these anti-immigration policies created social control by marginalizing Latinx groups and requiring them to prove citizenship (ACLU, 2011).

Shortly after SB 1070 was signed by then-governor Jan Brewer in 2010, the American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU) and the U.S. Department of Justice filed lawsuits challenging the law, charging that it is unconstitutional and encourages racial profiling. Many victories to void and limit major portions of SB 1070 have led to racial and ethnic profiling of Latinx, Native Americans, Asian Americans, and others presumed to be “foreign” based on how they look or sound. Although it has been years since SB 1070 began terrorizing communities throughout Arizona, many are still reeling from the aftermath (ACLU, 2024).

Check Your Knowledge

Licenses and Attributions for Modern-Day Racialized Social Control

Open Content, Original

“Modern-Day Racialized Social Control” by Shanell Sanchez and Catherine Venegas-Garcia, revised by Jessica René Peterson, is licensed under CC BY 4.0.

“New Jim Crow” by Brooke Calton and Kelly Szott, revised by Jessica René Peterson, is licensed under CC BY 4.0.

Open Content, Shared Previously

Figure 3.15. “Police arrest a man during the riots on August 12” by New York World-Telegram – LOC is in the Public Domain.

Figure 3.16. “Fred Hampton and Benjamin Spock at a protest rally outside the Everett McKinley Dirksen U.S. Courthouse in Chicago, October 1969” by the Chicago Tribune is in the Public Domain.

Figure 3.17. “Black-Panther-Party-armed-guards-in-street-shotguns” by Revolutionary Suicide: Controlling the Myth of Huey Newton, University of Virginia, is included under fair use.

Figure 3.18. “U.S. Private Prison Populations” by Statista is licensed under CC BY-ND 3.0.

Figure 3.19. “Private Prisons in the United States” by Statista is licensed under CC BY-ND 3.0.

organized action intended to change people’s behavior (Innes 2003).

the unfair treatment of marginalized groups, resulting from the implementation of biases, and often reinforced by existing social processes that disadvantage racial minorities

rules a person must follow during probation

a category of people grouped because they share inherited physical characteristics that are identifiable, such as skin color, hair texture, facial features, and stature

an effort in the United States since the 1970s to combat illegal drug use by greatly increasing penalties, enforcement, and incarceration for drug offenders (Britannica 2023).

a group of people living in a defined geographic area that has a common culture

called the Black Panther Party, this group was formed by Black college students Huey P. Newton and Bobby Seale in California in 1966 in response to Black communities being terrorized by police brutality. Its initial goal was to observe police activity within Black communities and to protect against any attacks (History, 2023), and it later evolved to get more Black officials into elected political positions.

the enactment of specific policies to deter deviousness that disproportionately impacts people of color (Patel, 2018).

to look something without bias

the way people who belong to social groups or categories perceive, think about, feel about, and act towards and interact with people in other groups.

shared social, cultural, and historical experiences of people from common national or regional backgrounds that make subgroups of a population different

the network of laws and practices that enforce social control on communities of color and disproportionately funnel Black Americans into the criminal justice system; this strips them of their constitutional rights as a punishment for their offenses in the same way that Jim Crow laws did in previous eras

a series of immigration policies that disproportionately affect Latino communities through racial profiling.

when police use race or ethnicity as a primary or sole factor when choosing to engage with or take enforcement action against someone