4.3 Understanding Race and Crime: Biological and Psychological Explanations

In discussing who commits a crime, any discussion of race and ethnicity is bound to arouse controversy because of the possibility of racial and ethnic stereotyping. Biology, psychology, race, and crime have a long and contentious history beginning in Europe. Many critics have emerged of earlier biological and psychological work in this section, but it is important to note that at this time, this was considered scientific. The notion of people having inherited traits that lead them to a pathway of criminality became mainstream. Theorists were also arguing that criminals could be identified by physical attributes. In the late 19th and early 20th century, criminologists believed you could tell who a criminal was just by looking at them. Early criminologists in the United States and Europe seriously debated whether criminals have certain identifying facial features separating them from non-criminals.

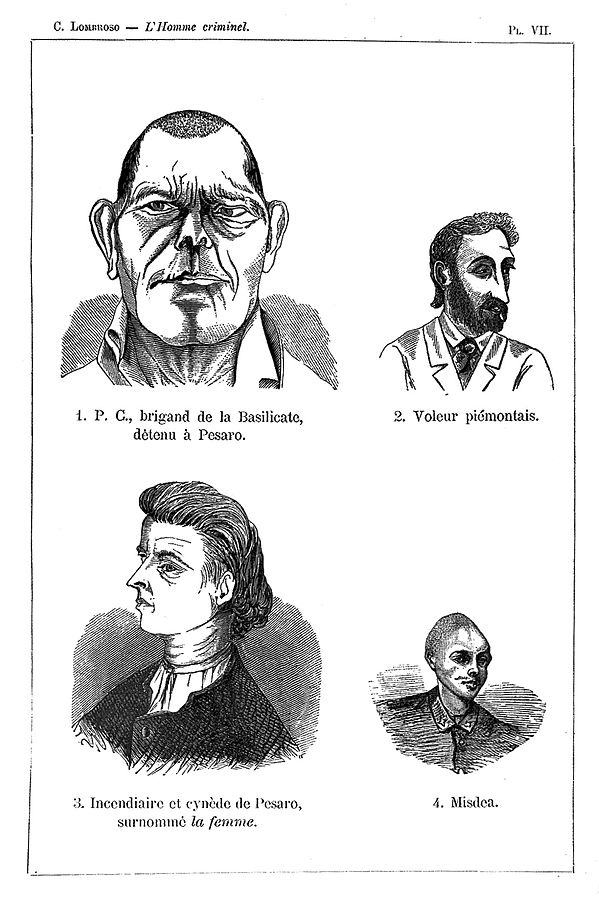

In the early 1870s, Cesare Lombroso, known as the “father of criminology,” because he was the first person to make crime and criminals a specific area of study, examined the dead body of a person who had gone to prison for theft and arson and noted an indentation on the back of his skull. Lombroso thought the dent resembled those found on ape skulls. Lombroso (1876) wrote:

At the sight of that skull, I seemed to see all of a sudden, lighted up as a vast plain under a flaming sky, the problem of the nature of the criminal—an atavistic being who reproduces in his person the ferocious instincts of primitive humanity and the inferior animals. Thus were explained anatomically the enormous jaws, high cheekbones, prominent superciliary arches, solitary lines in the palms, extreme size of the orbits, handle-shaped or sessile ears found in criminals, savages, and apes, insensibility to pain, extremely acute sight, tattooing, excessive idleness, love of orgies and the irresistible craving for evil for its own sake, the desire not only to extinguish life in the victim, but to mutilate the corpse, tear its flesh, and drink its blood. (Bretherick, 2015)

White men before Lombroso had used these pseudosciences to advance racist theories, and now he was using them to develop the field of “criminal anthropology.” Lombroso also relied on racist stereotypes, often correlating the physical attributes of people of color to crime. He stated, “oblique eyelids, a Mongolian characteristic,” and “the projection of the lower face and jaws (prognathism) found in negroes” were some of the features he singled out as indicative of criminality. Lombroso described facial features he thought corresponded to specific kinds of crime (Little, 2023). Lombroso was seen as an expert who provided advice in criminal cases. In a case where a man sexually assaulted and infected a 3-year-old girl, Lombroso bragged that he singled out the perpetrator from among six suspects based on his appearance. “I picked out immediately one among them who had obscene tattooing upon his arm, a sinister physiognomy, irregularities of the field of vision, and also traces of a recent attack of syphilis,” he wrote in his 1899 book (Little, 2023).

Today, we recognize there is no scientific data to support this false premise of a “born criminal,” which played a role in shaping the field we now know as criminology. Though the specific premise that physical features correspond to criminality has been debunked, we still see its influence in modern debates about the role of nature versus nurture. For example, after Ted Bundy’s arrest, many commented on how the handsome law student “didn’t look like” a serial killer (Little, 2023). What made the work of Lombroso and other theorists like him so powerful was that racial and ethnic groups were seen as inferior people who were damaging society. Theorists were connecting people of color, especially African Americans, to apes or nonhuman primates to argue that the white race was superior. Even as theorists in the 1980s attempted to suggest biological traits or inherited traits to explain the crimes of people of color, a major critique is that there was no focus on explaining crimes by whites.

Learn More: Historical Connections Regarding Curriculum Control

In 1859, Charles Darwin wrote The Origin of Species, which discussed the theory of evolution. He would later go on to write The Descent of Man, in which he argued that humans were most likely descendants of hairy, four-legged creatures rather than being independently created. Darwin’s findings about evolution helped inspire George William Hunter’s 1914 book, A Civic Biology, which was later used in schools to teach about biology. However, because evolution argued that the origin of humans began as descendants of primate-like ancestors instead of being created by God, it was criticized as being anti-religion. As a result, evolution was a very controversial topic at the time. As a way to keep religion in schools, the Butler Act was passed in Tennessee, which made teaching about evolution in schools a misdemeanor. In an attempt to counter the act, the American Civil Liberties Union made a pact with high school science teacher John Scopes to have him tried in court for teaching evolution. The Scopes Trial, also known as the Scopes Monkey Trial, was a highly publicized legal trial that argued against Tennessee’s 1925 Butler Act. Originally, Scopes was found guilty of violating Tennessee law, but this ruling was later overturned. However, the case brought up discussions about the separation of church teachings within school settings.

Think back to the activity in Chapter 3; in contemporary times, this case mirrors Florida legislation, which passed a bill banning schools from teaching critical race theory (described in more detail later). This law prevents schools from teaching subjects such as systemic racism, white privilege, and other racial issues to avoid the discomfort of parents and students. Efforts from conservative groups throughout the United States have targeted books with topics on race and LGBTQIA+ folks (Harris and Alter, 2023). Groups such as Moms For Liberty and Utah Parents United often don’t agree with the viewpoints in these books. Another example of banning concepts in school was the various bans on books within schools. Many of these books deal with sexual orientation, ethnicity, gender, systemic racism, and race. The Scholastic Book Fair, an event at schools that sells books in schools, has also recently removed “controversial” books from its in-person event (Jones, 2023). Since state laws have begun banning what issues can be taught in schools, books highlighting racial issues and gender expression are being forcibly removed from institutions. Criminal charges are being brought against librarians, school districts, and teachers due to these strict censoring laws.

If you are interested in learning more, watch a summary of the Scopes Trial [Website] or view the Timeline: Remembering the Scopes Monkey Trial: NPR [Website] (also found in the ).

IQ, Criminality, and Racism

In 1961, psychologist Arthur Jensen divided intelligence into two different categories: associative learning and conceptual learning. Associative learning is the simple retention of input or the memorization of facts and skills, such as when you study for an exam and memorize facts you know will be on the test. Conceptual learning is the ability to manipulate and transform information input or problem-solving, such as when that same test has open-ended questions that ask you to think critically about a challenge and offer up possible solutions.

Jensen tested children of color in the 1960s and reached two conclusions. First, Jensen concluded that 80 percent of intelligence is genetic, and the remaining 20 percent is due to environmental factors. This claim spoke directly to the “nature versus nurture” debate, with Jensen arguing that nature (genetics) has more influence on intelligence than nurture (the environment in which a child is raised). Second, he claimed that while all races were equal in terms of associative learning, conceptual learning occurred with a significantly higher frequency in white children than in Black children. This research led Jensen to incorrectly conclude that white people were inherently more able to engage in conceptual learning than Black people. Similarly, Nobel laureate and physicist William Shockley (1967) stated that the difference between Black American and European American IQ scores was due to genetics. He claimed that genetics might also explain the variable poverty and crime rates in society.

Arthur Jensen was arguably the father of modern academic racism. For over 40 years, Jensen, an educational psychologist at the University of California, Berkeley, pushed pseudoscientific theories of Black inferiority and segregationist public policies (SPLC, n.d.). Jensen’s work was widely used by segregationists as evidence in lawsuits against integration, in testimony before Congress, and propaganda from organizations like the Ku Klux Klan (SPLC, n.d.). Because criminological research argued that genetics impacted higher crime rates, people often supported policies that harmed communities of color. Many of the current biological theories have been countered with psychological and sociological explanations, or some combination of the two.

In 1994, psychologist Richard Hernstein and political scientist Charles Murray published The Bell Curve: Intelligence and Class Structure in American Life, which soon became controversial. In the book, they conclude that low IQ is a risk factor for criminal behavior. In particular, they claim that the more experience white men have in the criminal justice system, the lower their IQ. Hernstein and Murray suggest that low intelligence can lead to criminal behavior by being associated with the following experiences:

- lack of success in school and the job market

- lack of foresight and a desire for immediate gains

- unconventionality and insensitivity to pain or social rejection

- failure to understand the moral reasons for law conformity.

They argue that it is cognitive disability rather than economic or social disadvantage that creates crime. Because of this, policy should focus on cognitive problems instead of social problems, such as unemployment and poverty. If you want to learn more about bell curve flaws, see the article in the .

Hernstein and Murray’s study received criticism because of their outdated views of intelligence and their claim that it is difficult to increase IQ scores, despite evidence to the contrary. They also explained high crime among Black Americans as being due to inherited intellectual inferiority. What Hernstein and Murray failed to consider were alternative criminogenic risk factors, such as the impact of systemic racism on school quality. By portraying people who committed offenses as criminals because of cognitive disadvantage, their research justified repressive crime policies that focused primarily on the individual and not the environment.

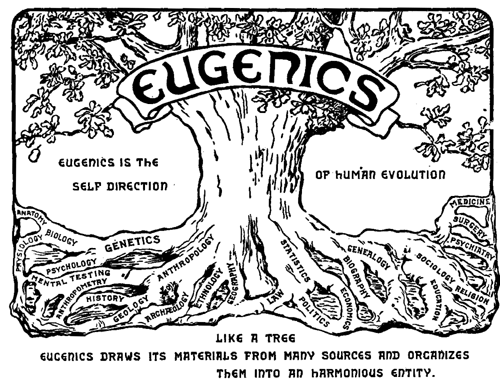

It is important to note that the research and theories making claims about intelligence and race have been disproven and determined to be both racist and misleading. These claims are part of the scientific racism ideology that “appropriates the methods and legitimacy of science to argue for the superiority of white Europeans and the inferiority of non-white people whose social and economic status have been historically marginalized” (National Human Genome Research Institute, 2022). Nonetheless, we look at IQ testing in a book on criminology because these factors were used in deciding whether someone was a criminal. This label not only led to people being incarcerated or institutionalized, but it also led to their murder. For example, in Virginia, it was legal to forcibly sterilize someone with a low IQ score, and in Nazi Germany, it was legal to murder children with scores below average. All of this horror was part of the eugenics movement in which the criminal justice system and criminologists played a key role.

Learn More: Eugenics as Crime Policy

Prejudice combined with poor and/or deeply biased methodologies produced research results that upheld white supremacy and patriarchal ideals. English anthropologist Francis Galton argued that “criminal nature tends to be inherited,” citing Richard Dugdale’s study of the Jukes family as justification. Galton coined the term eugenics, which refers to the manipulation of the human gene pool by controlling reproduction and/or eliminating populations deemed inferior. By preventing individuals of “degenerate” stock from procreating, he believed that eugenics could reduce crime and other social ills in later generations (Figure 4.7).

The eugenics movement was largely fueled by the idea that we could identify the inferior people through IQ testing. For a more modern comparison, think of standardized tests. Initially, these may appear fair since they are standard and given to everyone. However, there are a variety of factors that these tests fail to account for. For example, learning disabilities that have nothing to do with innate intelligence or critical thinking capabilities, but that impact individuals’ ability to read or respond quickly, can affect test scores. General anxiety or anxiety related to testing may also impact test scores. Furthermore, language abilities can impact test scores. If you are an American who speaks English, you probably wouldn’t score as high on an exam given in French or on an exam that you took in Ireland, where cultural differences have filtered into the English spoken there. Any time we see differences between populations in society, we have to look at the entire picture to understand those differences because they do not occur independently of culture, social structure, and legal systems (especially those meant to oppress certain groups).

Personality Theory

Another group of theories was personality theories, often attributed to Hans Eysenck, used to explain criminality. According to his theory, there is a biological basis to personality that arises from our genetics. Extroverts are sociable and outgoing and readily connect with others, whereas introverts have a higher need to be alone, engage in solitary behaviors, and limit their interactions with others (Boundless, n.d.). Eysenck was caught up in the controversy over racial differences in intelligence testing. Eysenck, however, offered something for the average person: two books on how to measure your IQ (Eysenck, 1962, 1966). Eysenck argued that behavior was controlled through conditioning or inherited traits. Conditioning is personality traits and behavioral characteristics that people learn and inherit are genetic. Eysenck’s criminal personality theory claimed that two personality types had the greatest tendency for criminal behavior: neurotic extroverts and psychotic extroverts. Psychotic extroverts are cruel, insensitive to others, and unemotional. Most of Eysenck’s work has since been rejected, but that did not stop his influence on others. Today, psychology researchers at the University of Oregon think they are getting closer to knowing whether personality and morality can be used to predict whether people adopt prejudicial beliefs. Cameron Kay and Sarah Dimakis attempted to identify the reasons people hold discriminatory beliefs. They found that people high in antagonistic personality traits such as Machiavellianism, narcissism, and psychopathy were more likely to endorse negative beliefs about homosexual and transgender people, including the belief that gay men should not be allowed to work with children and that gender affirmation surgery is morally wrong. “At the broadest level, there is very little conceptualization of prejudice within personality,” Kay said. “It isn’t thought of as an aspect of personality. In the past, people have shown that certain personality traits are associated with racism or xenophobia toward immigrants, and this is kind of an additional piece in that puzzle, telling us there is a way we can predict prejudice. It’s through personality” (2023). Many of the theories we discussed here either directly or indirectly relate to race and ethnicity.

Check Your Knowledge

Licenses and Attributions for Understanding Race and Crime: Biological and Psychological Explanations

Open Content, Original

“Theories of Biology, Psychology, Race, and Crime” by Shanell Sanchez, revised by Jessica René Peterson, is licensed under CC BY-NC-SA 4.0.

Open Content, Shared Previously

“Learn More: Eugenics as Crime Policy” by Jessica René Peterson and Taryn VanderPyl, “4.6 Eugenics as Crime Policy,” Introduction to Criminology: An Equity Lens, Open Oregon Educational Resources, revised by Jessica René Peterson, is licensed under CC BY 4.0.

“IQ, Criminality, and Racism” is adapted from “4.5 Crime and Intelligence” by Curt Sobolewski, Taryn VanderPyl, and Jessica René Peterson, Introduction to Criminology: An Equity Lens, Open Oregon Educational Resources, revised by Jessica René Peterson, which is licensed under CC BY 4.0. Modifications by

“Personality Theory” is adapted from “Eysenck: Dimensions of Personality” by The American Women’s College Psychology Department and Michelle McGrath, PSY321 Course Text: Theories of Personality, revised by Jessica René Peterson, is licensed under CC BY 4.0.

“Biology, Psychology, Race, and Crime” is adapted from:

- “Who Commits Crime” by the University of Minnesota, Social Problems, licensed under CC BY-NC-SA 4.0.

- “Theoretical Perspectives in Sociology” and “The History of Sociology” by Tonja R. Conerly, Kathleen Holmes, and Asha Lal Tamang, Intro to Sociology 3e, OpenStax, licensed under CC BY 4.0.

- “Sociological Theoretical Perspectives” by Erika Gutierrez, Janét Hund, Shaheen Johnson, Carlos Ramos, Lisette Rodriguez, and Joy Tsuhako, ETH 202: Racial and Ethnic Relations, Long Beach City College, Cerritos College, and Saddleback College, licensed under CC BY-NC-SA 4.0.

Modifications by Shanell Sanchez, revised by Jessica René Peterson, licensed under CC BY-NC-SA 4.0, include remixing, expanding, and editing for style. Portions of “Who Commits Crime” are remixed in the fourth and fifth paragraphs.

Figure 4.5. “Criminals from Cesar Lombroso’s L’Homme Criminel, Rome” by Cesar Lombroso, Wellcome Trust, is licensed under CC BY 4.0.

Figure 4.6. “The House of Leaves – Burning 4” by LearningLark is licensed under CC BY 2.0.

Figure 4.7. “Eugenics congress logo” is in the Public Domain.

All Rights Reserved Content

“Scientific Racism” definition from the National Human Genome Research Institute is included under fair use.

a category of people grouped because they share inherited physical characteristics that are identifiable, such as skin color, hair texture, facial features, and stature

shared social, cultural, and historical experiences of people from common national or regional backgrounds that make subgroups of a population different

traits and characteristics people have due to genetics

scientific explanations of things happening around us, such as patterns in social behavior, and how certain things are related

widely held beliefs or assumptions about a group of people based on perceived characteristics.

a group of people living in a defined geographic area that has a common culture

the idea that institutional racism is so embedded in the legal institutions of the United States that law functions to create and maintain inequalities between white and Black people

refers to how racism is embedded in the fabric of society and how institutional processes are used to maintain systematic discrimination through the complex interactions of large scale societal systems, practices, ideologies, and programs that produce and perpetuate inequities for racial minorities. Also referred to as institutional or structural racism.

the special benefits, protections, and access to the power conferred onto white people

a form of prejudice that refers to a set of negative attitudes, beliefs, and judgments about whole categories of people, and about individual members of those categories because of their perceived race and ethnicity.

ideology that “appropriates the methods and legitimacy of science to argue for the superiority of white Europeans and the inferiority of non-white people whose social and economic status have been historically marginalized”

an individual attitude based on inflexible and irrational generalizations about a group of people and literally means “judging before.”

the racist belief that white people are superior to people of other races and ethnicities

a group’s shared practices, values, and beliefs.

personality traits and behavioral characteristics people learn