4.4 Understanding Race and Crime: Sociological Paradigms

As discussed previously, paradigms are broad philosophical assumptions, whereas theory is more specific and refers to a set of concepts and relationships scientists use to explain the social world. Theories are more concrete, while paradigms are more abstract. We often find theorists follow specific paradigms when creating theoretical explanations. In this section, we will specifically focus on some broad sociological paradigms that relate to understanding race and crime. For example, conflict theorists examine power disparities and struggles between various racial and ethnic groups. Interactionists see race and ethnicity as important sources of individual identity and social symbolism. The concept of cultural prejudice recognizes that all people are subject to stereotypes that are ingrained in their culture. Intersectional theories remind us to consider how race, gender, and social class not only impact our social structures and our social interactions but are also ingrained within our social institutions. As a more radical critique of the status quo, critical race theory – described in greater detail later – centralizes the focus on race to understand our history, our contemporary society, and our social structures, as well as solutions to inequality.

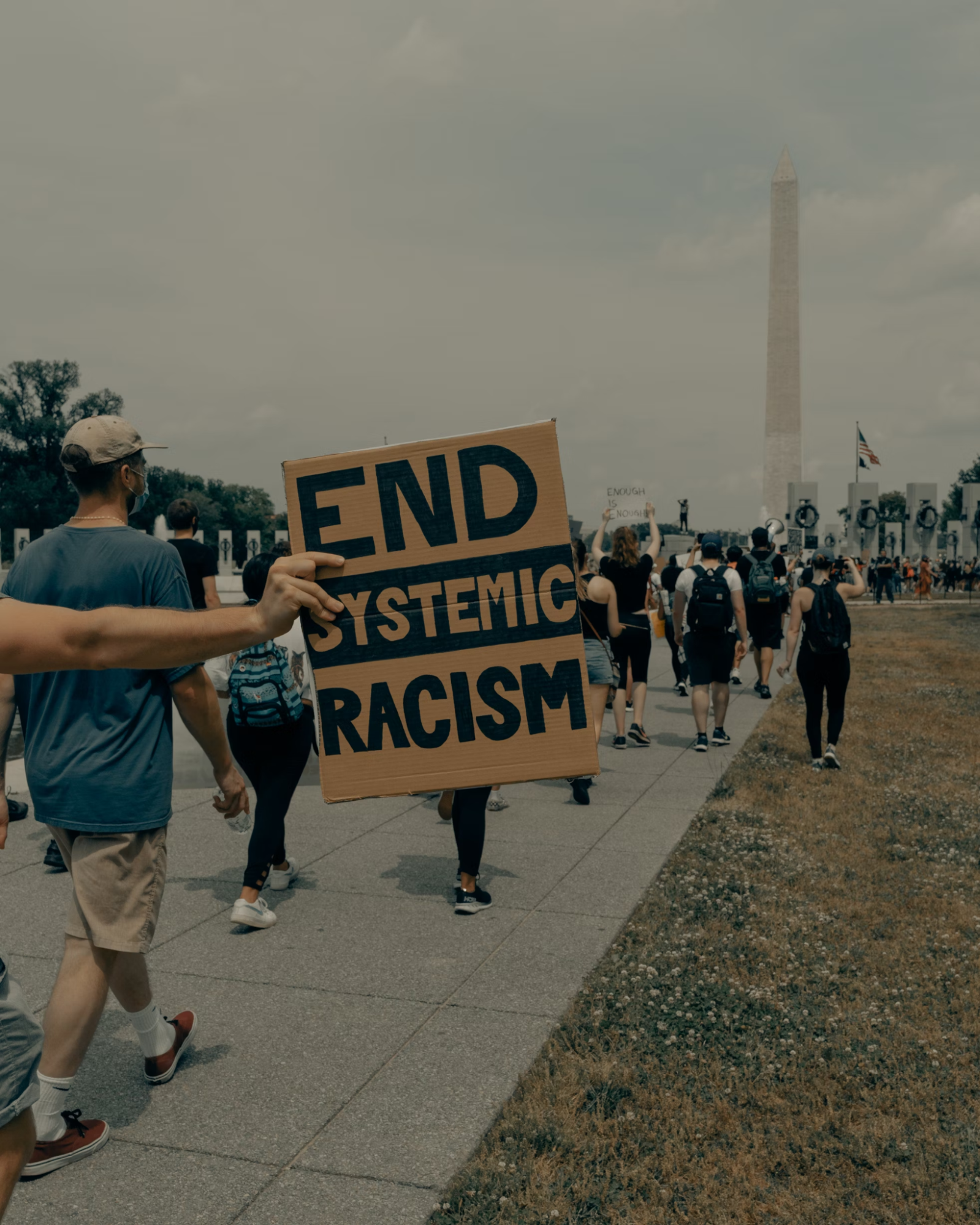

Functionalism emphasizes that all the elements of society have functions that promote solidarity and maintain order and stability in society. Hence, we can observe people from various racial and ethnic backgrounds interacting harmoniously in a state of social balance. Problems arise when one or more racial or ethnic groups experience inequalities and discrimination. This creates tension and conflict, resulting in temporary dysfunction of the social system. In the view of functionalism, racial and ethnic inequalities must have served an important function to exist as long as they have. This concept, of course, is problematic. How can racism and discrimination contribute positively to society? A functionalist might look at “functions” and “dysfunctions” caused by racial inequality. For example, the killing of George Floyd, a Black man, by a white police officer in 2020 stirred up protests demanding racial justice and changes in policing in the United States. To restore the society’s pre-disturbed state or to seek a new equilibrium, the police department and various parts of the system require changes and compensatory adjustments.

Another way to apply the functionalist perspective to race and ethnicity is to discuss the way racism can contribute positively to the functioning of society by strengthening bonds between in-group members through the ostracism of out-group members. Consider how a community might increase solidarity by refusing to allow outsiders access. On the other hand, Rose (1951) suggested that dysfunctions associated with racism include the failure to take advantage of talent in the subjugated group and that society must divert from other purposes the time and effort needed to maintain artificially constructed racial boundaries. Consider how much money, time, and effort went toward maintaining separate and unequal educational systems before the civil rights movement.

According to Robert Merton, there are manifest functions of social institutions, which are intended outcomes of policies. The latent functions of social institutions and their policies are not deliberate or intended, but still produce beneficial outcomes. For example, while it is not an intended outcome, schools in an urban community may lead to an increase in interracial friendships and relationships, which is a beneficial outcome for the larger community and society. According to Merton, a dysfunction would be considered a harmful latent outcome of an institutional policy or practice. For example, New York City’s “Stop-and-Frisk” policy was intended to provide police officers with more latitude in questioning and apprehending potential criminals (learn more about this in Chapter 5). However, the policy led to a disproportionate stopping and detention of Black and Latinx men and was ultimately deemed unconstitutional by the courts. In addition to unfair racial harassment, latent dysfunction would also include a growing distrust of the police and racial minorities feeling unsafe in their neighborhoods.

Conflict theories examine society through the lens of power struggles and inequality. Conflict theories are often applied to inequalities of gender, social class, education, race, and ethnicity. A conflict theory perspective of U.S. history would examine the numerous past and current struggles between the white ruling class and racial and ethnic minorities, noting specific conflicts that have arisen when the dominant group perceived a threat from people of color. In the late 19th century, the rising power of Black Americans after the Civil War resulted in draconian Jim Crow laws that severely limited Black political and social power. For example, Vivien Thomas (1910–1985), the Black surgical technician who helped develop the groundbreaking surgical technique that saved the lives of “blue babies,” was classified as a janitor for many years, and paid as such, even though he was conducting complicated surgical experiments. The years since the Civil War have shown a pattern of attempted disenfranchisement, with gerrymandering and voter suppression efforts aimed at predominantly minority neighborhoods.

Symbolic interactionism is a micro-level theory that focuses on meanings attached to human interaction, both verbal and non-verbal, and to symbols. An important element is communication because it allows for the exchange of meaning through language and symbols, which helps people make sense of their social worlds. For symbolic interactionists, race and ethnicity provide strong symbols as sources of identity. Some interactionists propose that the symbols of race, not race itself, are what lead to racism. Herbert Blumer (1958) suggested that racial prejudice is formed through interactions between members of the dominant group. Without these interactions, individuals in the dominant group would not hold racist views. Culture of prejudice refers to the argument that prejudice is embedded in our culture. We grow up surrounded by images of stereotypes and casual expressions of racism and prejudice. Consider the casually racist imagery on grocery store shelves or the stereotypes that fill popular movies and advertisements. Because we are all exposed to these images and thoughts, it is impossible to know to what extent they have influenced our thought processes.

Symbolic interactionists also focus on the process of labeling people or providing meanings attached to labels and their social consequences. The social construction of race is reflected in the way names for racial categories change with changing times. It’s worth noting that race, in this sense, is also a system of labeling that provides a source of identity; specific labels fall in and out of favor during different social eras. A symbolic interactionist might say that this labeling has a direct correlation to those who are in power and those who are labeled. For instance, if a teacher labels their students as either “intelligent and motivated” or “slow and lazy” based on racial and ethnic stereotypes, this could impact interactions in the classroom and may also lead to an internalization of those stereotypes and lower academic performance (Rist, 1970; Steele, 2010). Indeed, as these examples show, labeling theory can significantly impact a student’s schooling.

The Importance of Intersectionality

Intersectionality is a perspective and a theory that analyzes and interrogates the ways race, class, gender, sexuality, and other social structures of privilege and oppression overlap and work together. Early Black feminist theorists built the foundation for the study of feminist intersectionality. The concept of intersectionality emerged from a critique of white feminist theory and activism that ignored the experiences of Black and Indigenous women of color. Ana Julia Cooper and Ida Wells-Barnett brought a sociological consciousness to their response to the Black experience and focused on the toxic interaction between difference and power in U.S. society (Madoo and Niebrugge, 1998). Cooper and Wells-Barnett looked at society through the lenses of race, gender, and class. Although they worked separately, they created a Black feminist sociology together. They both pointed out that “domination rests on emotion, a desire for absolute control” (Madoo and Niebrugge, 1998:169). Their point was that societal domination is not just about making a profit or otherwise increasing one’s financial status. Rather, there is an emotional factor within societal domination.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=0TFy4zRsItY

Cooper (1892) provides an example by noting the extra expense paid by railroad companies in providing a separate car for people of color. On June 7, 1892, Homer Plessy, an African American man, bought a first-class train ticket from New Orleans to Covington, Louisiana. He sat in the white’s whites-only train car, despite the racial title that was meant to bar him from doing so. The train conductor and a private detective were in place to arrest Plessy when he refused to remove himself to the “colored” car, thus placing him in court for violating the Separate Car Act of 1890 and starting the case that eventually led to the historic U.S. Supreme Court ruling Plessy v. Ferguson. Homer Plessy agreed to be the plaintiff in Plessy v. Ferguson because he was of mixed race; he described himself as “seven-eighths Caucasian and one-eighth African blood” (History, 2017). The Separate Car Act of 1890 required all passenger railways to have separate train car accommodations for Black and white Americans. Black people were slowly gaining influence and pushing against racial norms. This was unfamiliar and frightening to white Americans, and this fear, especially in the South, prompted a greater desire to separate the races and create more regulations (Georgia College & State University, n.d.). On May 18, 1896, four years after the arrest, the U.S. Supreme Court ruled that the protections of the Fourteenth Amendment only applied to political and civil rights (such as voting and jury service), not to social rights (such as sitting on a railcar), and so began “separate but equal” laws.

These Black feminist founders of sociological thought planted the seeds for the emergence of influential sociological theory from the 1980s and 1990s, which centered on the experiences of Black and Indigenous women of color. Though the concept of intersectionality is most often attributed to critical race legal scholar Kimberlé Crenshaw, within the field of sociology, Patricia Hill Collins (1948–) is recognized for providing complex and detailed analyses of the concept. Her theorization of the “outsider within” perspective shows how Black women “have a clearer view of oppression than other groups” whose identities are different (1986:20). Collins (1986) details how Black women participate in social systems but not as insiders, given their oppression. Participating in a social system that oppresses them, Black women have a unique standpoint that offers more information. They can see more clearly how our social structures of race and gender work intersectionally.

Collins’s (1986) theory of interlocking oppressions points out philosophical foundations that underlie multiple systems of oppression. It is common in sociology to explain inequality in terms of race, class, or gender alone. Either you are Black or white, male or female, young or old, and so on. One group in each dichotomy has more power than the other. With some additional complexity, sociologists discuss issues of oppression related to race and class or age and gender, for example. Collins argues that these either/or additive approaches missed the point.

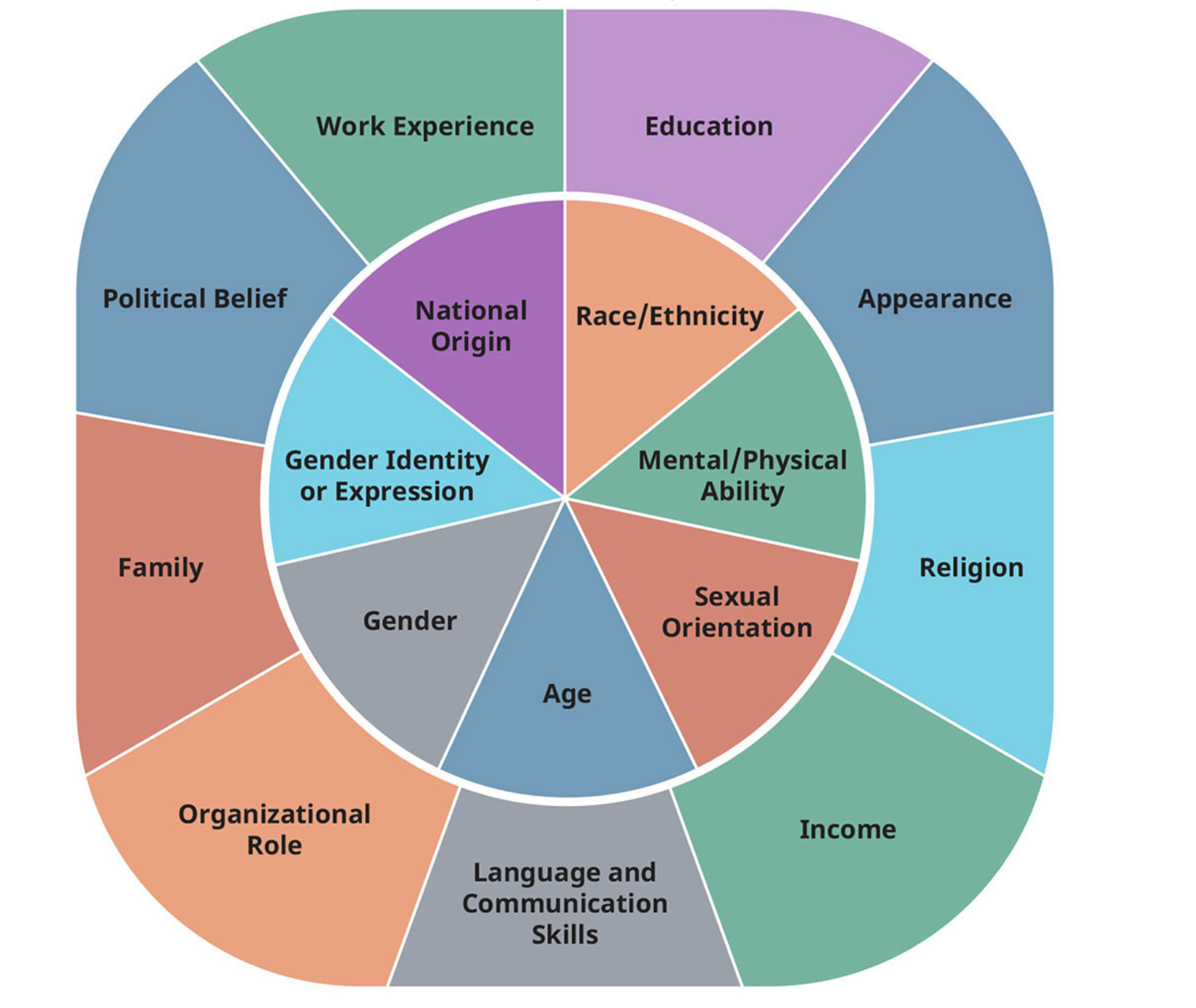

Instead, Collins explains that oppression exists as a matrix of domination, a concept that says that society has multiple interlocking levels of domination that stem from the societal configuration of race, class, and gender (Andersen and Collins, 1992). Patriarchy and ableism work together to make disabled women and nonbinary people invisible. Systemic racism, homophobia, and classism interlock to oppress transgender people of color who don’t have much money. This Black feminist analysis sees the holistic experience of interlocking and simultaneous oppressions and challenges people to see wholeness instead of difference (Collins, 1986). Black feminist sociologist Patricia Hill Collins (1990) developed intersectionality theory, which suggests we cannot separate the effects of race, class, gender, sexual orientation, and other attributes. When we examine race and how it can bring us both advantages and disadvantages, it is important to acknowledge that the way we experience race is shaped, for example, by our gender and class. Multiple layers of disadvantage intersect to create the way we experience race. For example, if we want to understand prejudice, we must understand that the prejudice focused on a white woman because of her gender is very different from the layered prejudice focused on a poor Asian woman, who is affected by stereotypes related to being poor, being a woman, and her ethnic status.

“Intersectionality is not just a form of inquiry and critical analysis but necessarily also a form of praxis that challenges inequalities and opens a collective space for both recognizing common threads across complex experiences of injustice and responding to them politically” (Ferree, 2018). Using an intersectional lens to analyze social systems, it is useful to consider how capitalism, racism, sexism, heterosexism, ageism, and/or ableism intertwine to stratify society and impact life chances for individuals and groups. Collins and Bilge (2020) combine the critical inquiry into inequalities and stratification with critical praxis to advance social justice. Thus, intersectionality is not only a lens and theory but also a potential solution to social problems, reminding sociologists that the many status intersections of race, social class, gender, sexuality, age, and/or disability should be considered when seeking remedies to social ills. Another way to apply the interactionist perspective is to look at how people define their races and the race of others. Some people who claim a white identity have a greater amount of skin pigmentation than some people who claim a Black identity; how did they come to define themselves as Black or white?

Critical Race Theory

Kimberlé Crenshaw coined the term critical race theory, also commonly referred to by its acronym “CRT,” and notes that CRT is not a noun, but a verb. It critiques how the social construction of race and institutionalized racism perpetuate a racial caste system that relegates people of color to the bottom tiers. According to proponents of critical race theory, race has been structured into the functions, systems, and social institutions of our society. Critical race theory has been in the news a lot in recent years, as many states have attempted to ban it. If you want to learn more details about what CRT is—and isn’t—see the Legal Defense Fund website in the Chapter Resources section.

There are six basic tenets to CRT. First, racism is socially constructed, not biological. Second, racism in the United States is normal, not aberrational: it is the ordinary experience of most people of color and cannot be ignored. Around 5 percent of illicit drug users are Black people, yet Black people represent 29 percent of those arrested and 33 percent of those incarcerated for drug offenses. Further, Black people and white people use drugs at similar rates, but the imprisonment rate of African Americans for drug charges is almost six times that of white people (NAACP, 2023).

Third, legal advances (or setbacks) for people of color tend to serve the interests of dominant white groups due to what CRT scholars call “interest convergence” or “material determinism” (Duignan, 2025). Fourth, people of color often experience negative stereotypes, again depending on the needs or interests of white people. Such stereotypes are often reflected in popular culture (e.g., in movies and television) and literature as well as in the news media, and they have even influenced public schools. The National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) (2023) found that 65 percent of Black adults have felt targeted because of their race, and approximately 35 percent of Latinx and Asian adults have felt targeted because of their race. Negative stereotyping leads to more negative contact with the criminal justice system.

Fifth, no individual can be adequately identified by membership in a single group but by multiple intersectionalities. Last, the “voice of color” thesis holds that people of color are uniquely qualified to speak on behalf of other members of their group (or groups) regarding the forms and effects of racism (Duignan, 2025). One interesting statistic from the National Center for Education Statistics in 2021 found that 73 percent of faculty were white, specifically 35 percent white female and 38 percent white male. Further, these voices validate the perspectives of other people of color, which may diverge from the perspectives of the dominant group. For example, Ibram X. Kendi (2020) writes of an opportunity gap that exists in education, whereas predominantly white institutions frame this as an achievement gap, where the former places the problem with society, and the latter frames the problem as people of color themselves.

Finally, critical race theorists propose a variety of social reforms. Rather than colorblind solutions, critical race theorists advocate for race-conscious solutions to race-based social ills. “The system applauds affording equality of opportunity but resists programs that assure equality of results” (Delgado and Stefancic, 2001:23). For example, the institutional research performed by Janét Hund (2019) found when African American and Latinx community college students were taught by the same race-ethnic faculty, their course completion rates were higher; this research suggests that hiring more African American and Latinx faculty would serve to improve the course completion rates for African American and Latinx colleges students. Racial disparities in imprisonment are relatively large for drug and violent crimes, and these offenses account for a large share of the prison population. Tonry (2019) argues that changes in sentencing policy will reduce overall racial disparity in incarceration. In addition, in the federal system, the shift toward more punitive sentencing for drug crimes affected Black individuals more than white individuals, and drug offenses accounted for a significant portion of the growth in the federal prison population (Neal and Rick, 2016). To reduce racial inequality, policies must target those that disproportionately impact people of color.

Check Your Knowledge

Licenses and Attributions for Understanding Race and Crime: Sociological Paradigms

Open Content, Shared Previously

“Understanding Race and Crime: Sociological Paradigms” is adapted from:

- “Theoretical Perspectives in Sociology” and “The History of Sociology” by Tonja R. Conerly, Kathleen Holmes, and Asha Lal Tamang, Intro to Sociology 3e, OpenStax, which is licensed under CC BY 4.0.

- “Sociological Theoretical Perspectives” by Erika Gutierrez, Janét Hund, Shaheen Johnson, Carlos Ramos, Lisette Rodriguez, and Joy Tsuhako, ETH 202: Racial and Ethnic Relations, Long Beach City College, Cerritos College, and Saddleback College, which is licensed under CC BY-NC-SA 4.0.

- “What is Social Theory” by Kelly Stolz and Kimberly Puttman, Social Problems, is licensed under CC BY 4.0.

Modifications by Shanell Sanchez and Catherine Venegas-Garcia, revised by Jessica René Peterson, licensed under CC BY-NC-SA 4.0, include remixing, expanding, and editing for style.

Figure 4.8. “T’Challa Black Panther Movie Poster 2017 NYC 4981” by Brecht Bug is licensed under CC BY-NC-ND 2.0.

Figure 4.10. Image by Dr. Remi Alapo from “7.3 Race and Ethnicity,” Diversity and Multicultural Education in the 21st Century is licensed under CC BY-NC-SA 4.0.

Figure 4.11. Image by Clay Banks is licensed under the Unsplash License.

All Rights Reserved Content

Figure 4.9. “Kimberlé Williams Crenshaw: What Is Intersectional Feminism?” by Omega Institute for Holistic Studies is licensed under the Standard YouTube License.

scientific explanations of things happening around us, such as patterns in social behavior, and how certain things are related

a category of people grouped because they share inherited physical characteristics that are identifiable, such as skin color, hair texture, facial features, and stature

shared social, cultural, and historical experiences of people from common national or regional backgrounds that make subgroups of a population different

an individual attitude based on inflexible and irrational generalizations about a group of people and literally means “judging before.”

widely held beliefs or assumptions about a group of people based on perceived characteristics.

a group’s shared practices, values, and beliefs.

the idea that institutional racism is so embedded in the legal institutions of the United States that law functions to create and maintain inequalities between white and Black people

a group of people living in a defined geographic area that has a common culture

emphasizes that all the elements of society have functions that promote solidarity and maintain order and stability in society

the unfair treatment of marginalized groups, resulting from the implementation of biases, and often reinforced by existing social processes that disadvantage racial minorities

a form of prejudice that refers to a set of negative attitudes, beliefs, and judgments about whole categories of people, and about individual members of those categories because of their perceived race and ethnicity.

theories that examine society through the lens of power struggles and inequality, often applied to inequalities of gender, social class, education, race, and ethnicity

social research focusing on small groups and individual interactions.

sociological concept describing how labeling people or providing meanings attached to labels has real social consequences

theory which suggests we cannot separate the effects of race, class, gender, sexual orientation, and other attributes (Collins 1990)

the scientific and systematic study of human relationships, institutions, groups and group interactions, societies, and social interactions, from small and personal groups to large groups

theory exposing philosophical foundations that underlie multiple systems of oppression (Collins 1986)

a concept that says that society has multiple interlocking levels of domination that stem from the societal configuration of race, class, and gender (Andersen and Collins 1992)

refers to how racism is embedded in the fabric of society and how institutional processes are used to maintain systematic discrimination through the complex interactions of large scale societal systems, practices, ideologies, and programs that produce and perpetuate inequities for racial minorities. Also referred to as institutional or structural racism.