4.5 Understanding Race and Crime: Criminological Theories

The field of sociology has been incredibly influential in the development of criminological theories. So many elements of our lives – family, culture, demographics, relationships, religion, education, politics, the legal system, and more – are part of the equation for many sociological approaches to understanding crime. After the Second World War, sociologists expanded on previous sociological thought and dug deeper into why structures and practices of inequality persist. They also started to leverage new understandings of systems thinking and global interdependence. Though many of the most recognized classical theorists came from European white cultural backgrounds during the 19th century, plenty of Black, Indigenous, and people of color were creating social theory and adding to our understanding of social problems.

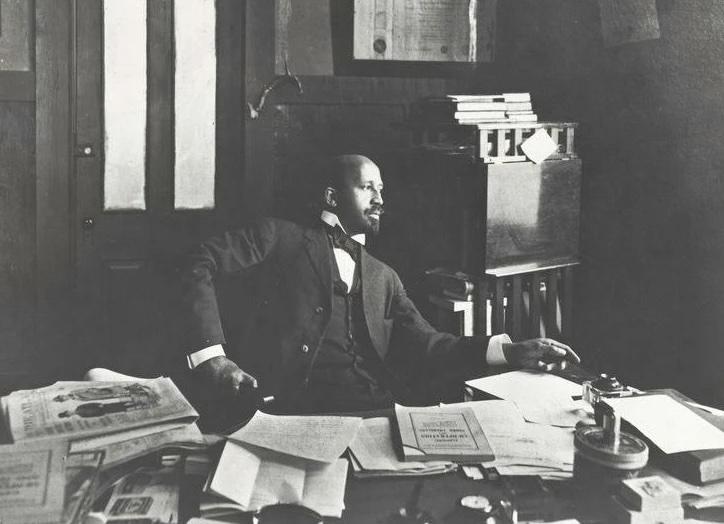

W. E. B. Du Bois was one of the first sociologists to publish scholarly work that discussed race and racism. In this way, he provided a critical intervention into sociological theory, and his writings critiqued the absence of racial analysis from previous social theory. He takes a systemic sociological approach to the experience of race. He describes how the experiences of white people and Black people are qualitatively different, and he collects and displays data that support his theories. He debates Booker T. Washington, who believes that formerly enslaved people need education and training to fix any issues in their lives. He writes:

[Washington’s] doctrine has tended to make the whites, North and South, shift the burden of the Negro problem to the Negro’s shoulders and stand aside as critical and rather pessimistic spectators; when in fact the burden belongs to the nation, and the hands of none of us are clean if we bend our energies to righting these great wrongs. (Du Bois, 1903:Section III)

Specifically addressing law and justice, Du Bois said:

Daily, the Negro is coming more and more to look upon law and justice, not as protecting safeguards, but as sources of humiliation and oppression. The laws are made by men who have little interest in him; they are executed by men who have no motive for treating Black people with courtesy or consideration; and, finally, the accused law-breaker is tried, not by his peers, but too often by men who would rather punish ten innocent Negroes than let one guilty one escape (Du Bois, 1903).

Du Bois says the United States is responsible for making changes that will create equality for formerly enslaved people. Second, Du Bois describes how Black people experience themselves differently from white people. One of his most influential contributions to sociological theory came from his discussion of the veil and double consciousness. He writes that the Black American is “born with a veil, and gifted with second-sight in this American world—a world which yields him no true self-consciousness, but only lets him see himself through the revelation of the other world” (1903:3). He points out that Black Americans have a double consciousness. They see themselves, and they see how white Americans see them. If interested, you can further explore the idea of race consciousness in the CNN project “The First Time I Realized I Was Black” in the Chapter Resources section.

Du Bois’ analysis continues to inform our experiences and conversations around race even today. Sociologists such as Du Bois have had a significant impact on criminology and how we understand race and crime. A lot of criminological theories are nestled under a sociological umbrella, meaning that they apply a sociological lens to the study of crime and assess the influence of sociological concepts, such as poverty or power, on offending behavior. The rest of this chapter will explore a few such theories that have been used to explain issues of race and crime; remember that some may be race-specific, while others may be race-neutral but remain relevant to the study of race and crime. To learn more about Du Bois’ data visualizations that explain institutionalized racism, see the Smithsonian article “Du Bois’ Data Visualizations” in the Chapter Resources section.

Strain Theory

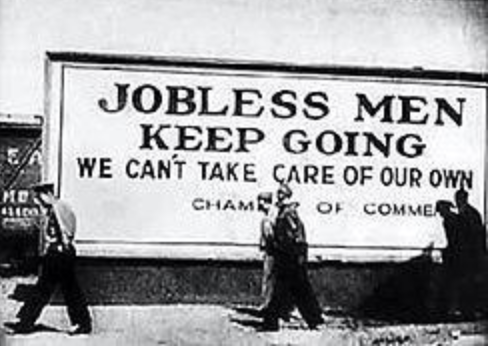

Robert Merton’s strain theory is that when someone faces strain, they experience a sense of normlessness and confusion about the rules in society (also known as anomie). When experiencing this state of confusion, someone might be willing to take alternative routes or use alternative means to get to the goals they want. In other words, if a big television is a symbol of success and happiness, someone may be willing to steal one if they cannot afford to buy one, so people think they are doing well. Merton witnessed this phenomenon firsthand during the Great Depression. He saw that people still valued American culture and its focus on economic success, but access to legitimate opportunities to reach that success was extremely limited. When confronted with the contradiction between culturally accepted economic goals and socially accepted (and limited) means of achieving success, many Americans experienced anomie, and that contradiction produced strain.

How does someone respond to this strain? The majority, according to Merton, accept their reality and conform by accepting that they need to accept lower goals that can be achieved through legitimate means. They achieve their level of success within the rules of society, even if they never reach their aspired goals. However, not everyone is willing or can adjust their goals, especially when being bombarded with constant messaging that they need more through social media, music, advertisements, television shows, movies, and more. Crime may be used to reduce or escape from strain, seek revenge against the source of strain or related targets, or alleviate negative emotions. For example, individuals experiencing chronic unemployment may steal or sell drugs to obtain money, seek revenge against the person who fired them, or take illicit drugs to feel better. Sociologist Robert Merton (1957) argued that U.S. society considers economic success an absolute value, hence the “American Dream.” As a result, the pressure to achieve economic success overrides any need to fit in with the rest of society’s rules and follow its laws.

Let’s think about how this theory might explain the impact of strain on different socioeconomic classes. Imagine a kid living in a high-income household. That child is likely to live in a nicer neighborhood with good recreational and health-related resources. They may have access to private schools, tutors, and extracurricular activities that result in a better education and higher chances of getting into college. Rather than taking a low-paying after-school job to help pay the bills or cover some of their expenses, a kid from a higher-income family may be able to volunteer their time or work in unpaid positions, which could give them access to career networks. From the very beginning, a higher socioeconomic status and social class provide individuals with opportunities that help them get closer to reaching our institutionalized goals. Those in lower socioeconomic classes do not have those same opportunities. And this is before even considering how racism, sexism, and other prejudices affect childhood and available opportunities.

Theories at this time examined American society and found a widely acknowledged goal to attain wealth and own a home with two cars in the driveway, a picket fence, and a dog. However, they highlighted that the “American Dream” was not possible for a lot of people, especially people of color. The general message was to work hard and follow socially accepted steps toward your goal, and you will be rewarded. This did not work out in reality for many Americans, and the distance between what someone wants to achieve and what they can achieve because of various obstacles and limitations is strained.

Learn More: Redlining and Its Impact on Communities of Color

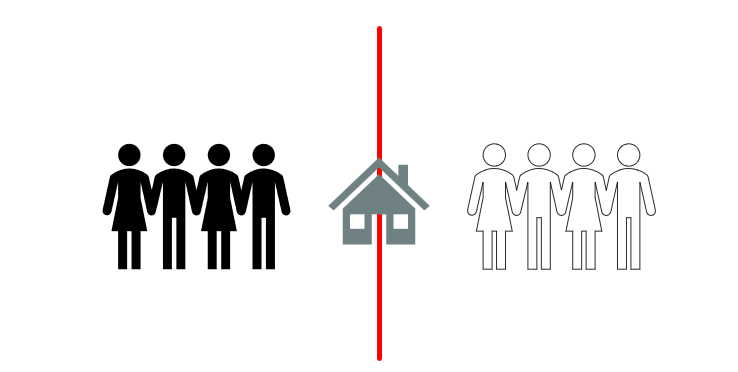

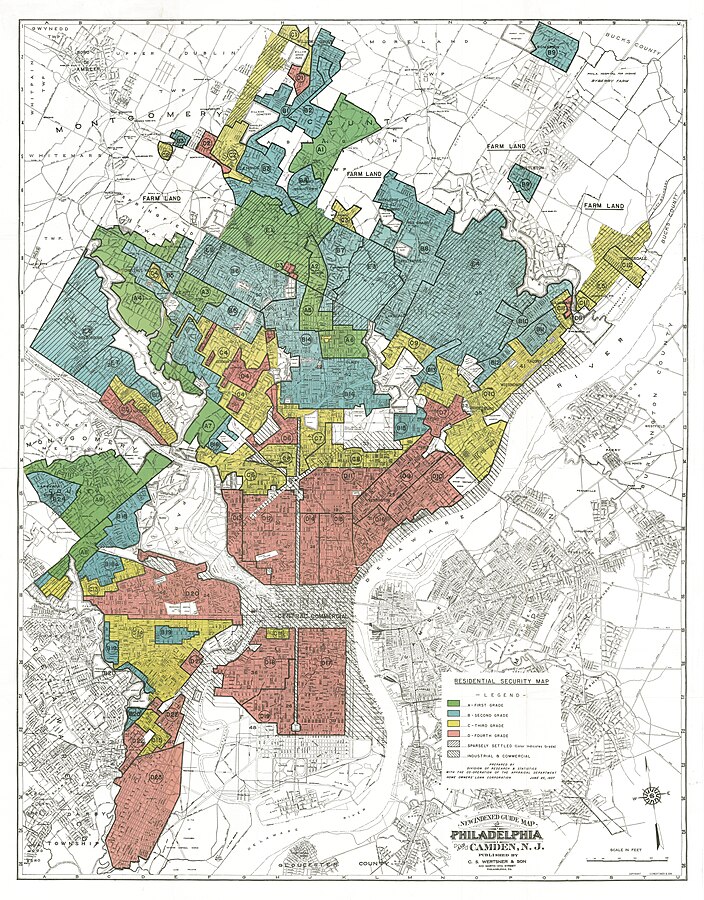

When talking about achieving the “American Dream,” Black and Brown individuals have significantly more obstacles. We can see one of these obstacles by analyzing the historical redlining of Black and Brown neighborhoods. Redlining, the process of outlining neighborhoods on maps to highlight which ones could be given loans, was created in the 1930s. During Franklin Roosevelt’s presidency, he implemented a loan program that offered assistance to potential home buyers. However, to identify which families should be given loans, redlining was created to differentiate between “good” and “bad” neighborhoods. These policies helped home buyers within the “good” or green-coded areas to easily get loans. Families within the redlined neighborhoods were labeled as bad, and their loan applications would be denied. These redlined communities were overwhelmingly populated by Black, Latinx, and other minorities. And even though redlining was banned years ago, the effects are still following current communities of color.

Consequently, one of the issues surrounding communities of color and redlining has come from the increased heatwave deaths. With climate change bringing extreme weather changes, neighborhoods in redlined areas have been experiencing higher temperatures compared to white neighborhoods (Cimons, 2020). Heatwaves have hit these communities harder, as access to cooling stations, air conditioners, and shade is regularly more limited. Unable to afford moving out of redlined areas, the effects of global warming and generational poverty will continue to affect communities of color in the future.

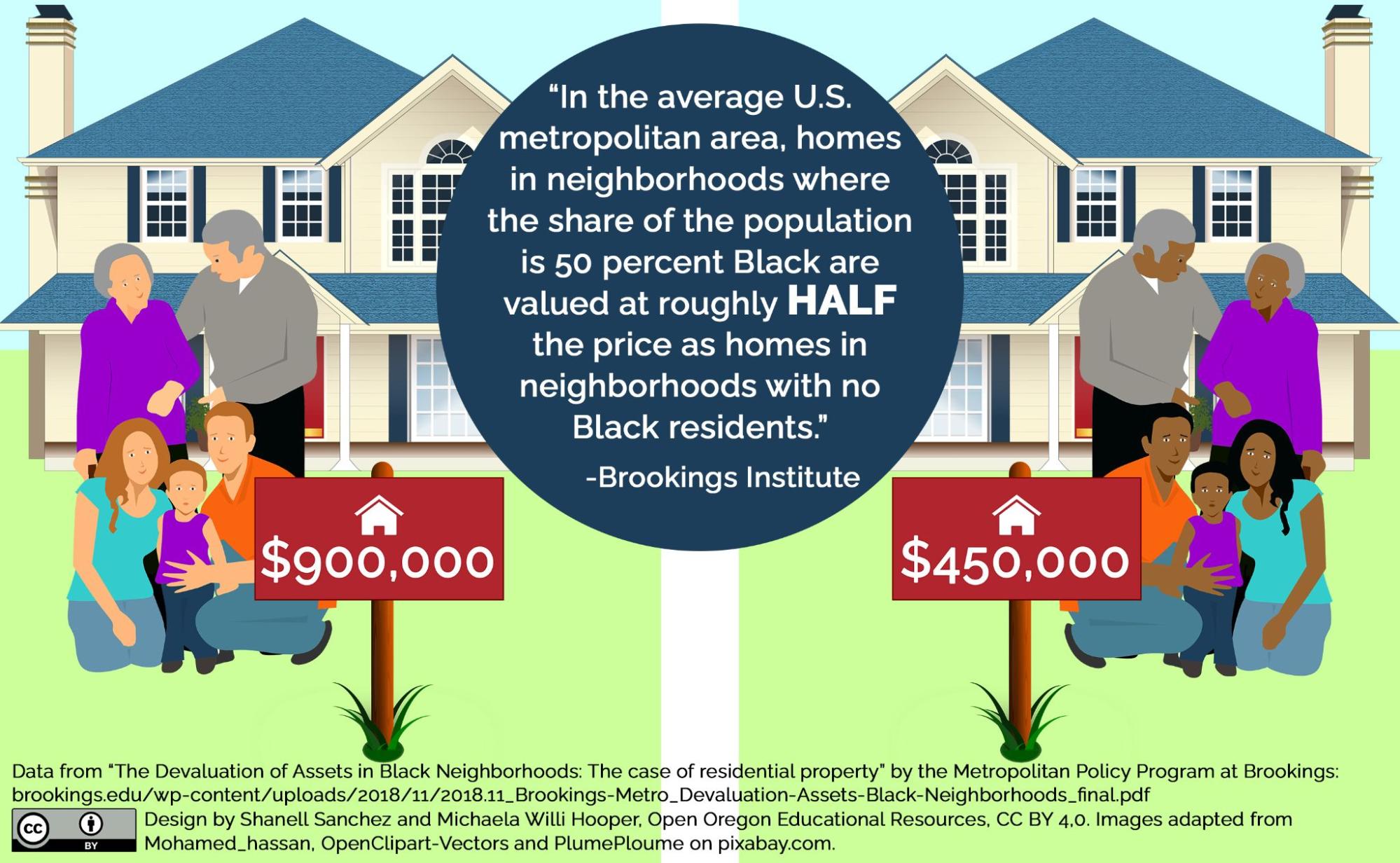

The figures below help illustrate the concept of redlining and its impact on people of color. If you want to learn more, you can watch the video “Adam Ruins Everything: Redlining” or read the article “Redlining and Heat Wave Risk” in the Chapter Resources section.

General Strain Theory

Robert Agnew expanded Merton’s strain theory to include short-term frustrations as possible causes of strain in an adolescent’s life. In general strain theory, Agnew argued that social injustice or inequality may be at the root of strain rather than the American Dream (1992). Agnew would point to that negative interaction as a strain in an individual’s life, particularly with adolescents. The feeling that the deck is stacked against them and there is no reason to attempt to live by society’s rules can lead an individual to criminal or delinquent behavior. Delinquency, according to Agnew, becomes a natural reaction to the stresses of adolescence.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ydca1wzlheg

Merton’s theory of strain depicted individuals working toward an unattainable goal, but Agnew’s theory suggests that some individuals are running away from something instead. This may include punishment by their parents or negative relationships that exist at school. According to Agnew (1992), adolescents are “pressured into delinquency by the negative affective states, most notably anger and related emotions, that often result from negative relationships.” Agnew said juveniles are likely to feel strain if they fail to achieve positively valued goals, lose something valuable to them (suspension from school, relationship breakup, death of a family member, divorce), and have the presence of negative stimuli (child abuse, victimization, negative school experiences).

All juveniles will experience at least one of these types of strain during their lives, so why do some participate in delinquent behavior while others do not? Agnew (1992) proposes four factors that predispose juveniles to delinquency. They reach the limit of their known coping strategies, so their reaction is anger and frustration. They experience chronic strain, which lowers their threshold for tolerance of adversity, meaning that juveniles are unable to deal with increasing levels of strain, acting out even when small events occur in their lives. The chronic strain is cumulative, building their anger into hostility and avoidance. As things get more difficult for them, they become prone to anger that focuses on those they perceive as causing their injustices. Delinquency is then the natural consequence of the strain in their lives.

Social Disorganization Theory

Social disorganization theory claims that neighborhoods with weak community controls caused by poverty, residential mobility, and ethnic heterogeneity will experience a higher level of criminal and delinquent behavior. One popular theory that came out of the Chicago School is the social disorganization theory. Sociologists Shaw and McKay (1942) looked at Chicago’s geographic distribution of crime and delinquency and found that areas of high crime were also characterized by weak community controls. The neighborhoods they studied that had consistently high crime rates consisted of mostly low-priced or subsidized rental properties, a large portion of the residents being on public assistance, and high rates of unemployment. This setting of poverty meant that those who lived in that area long-term were those who had no choice, versus those who moved out as soon as they gained some financial stability. There was no community building or getting to know others in the neighborhood, which is usually the source of informal social controls (keeping an eye on each other’s kids).

Sampson (1987) found a connection between Black male joblessness and economic deprivation and violent crime, often with female-headed households. The newer social disorganization theorists attempted to move away from “blaming the individual” or that certain groups of people were the issue. They argued that it is imperative to examine community-level factors such as high concentrations of poverty, racial segregation, residential mobility, family disruption, and more.

Status Frustration Theory

In his book Delinquent Boys: The Culture of the Gang, Cohen (1955) proposed status frustration theory, which argues that four factors – social class, school performance, status frustration, and reaction formation (coping methods) – contribute to the development of delinquency in juveniles. His theory assumes that crime is a consequence of the creation of youth subcultures in which deviant values and moral concepts dominate.

Cohen contended that middle-class goals serve as a measuring rod for societal success. When we think about achievement for adolescents, how is it measured? Through SAT scores? Extra-curricular activities? GPA? Does the measure of achievement look at the resources each child has been given? For instance, what if a student’s SAT score looked different if they came from a failing school compared with scores from students who attended a well-resourced school? Are SAT scores viewed differently if a child was able to pay to take a prep class compared to one who wasn’t able to afford one? In Cohen’s view, this is just part of the creation of the middle-class measuring rod, where students are set up to fail when they do not have access to the resources other students have. Students without support may not see value in education and end up not pursuing a higher degree because they believe they have already been set up to fail.

Like strain and general strain theories, the frustration that is created by not obtaining desired goals can lead to deviance. However, in all of these cases of strain and frustration, the majority of juveniles are not deviant and do conform to the proposed standards of society. However, those who move toward delinquency may be doing so because there is a sort of status they believe can be achieved through delinquency. Whether it be through violence, monetary delinquency, or just drug/alcohol use, these juveniles finally achieve a level of status they couldn’t achieve outside of their delinquent behavior. An interesting part of the school system is how, if a child misbehaves, the punishment is suspending or expelling them from school. If their grades don’t meet the minimum, then they may be removed from a sports team or other extracurricular activity that could have given them the status they desired, and the taking away of their activity could lead to frustration and possible deviant behavior.

Subculture Theory

Subculture theories argue that certain groups or subcultures in society have values and attitudes that are conducive to crime and violence. The dominant culture is the majority group that has its norms, values, and preferences that are imposed on everyone else. In the United States, the dominant group would be white people. This culture is forced on everyone as the accepted way to live, behave, and believe, whether or not groups who are not represented in this dominant majority agree, and even when they contradict what is preferred for smaller, less powerful groups. These other groups have their subculture, which may not align with the dominant culture.

A subculture is an identifiable subgroup within the larger culture whose values may differ from those present in the dominant group. This could include specific standards of behavior that are learned and passed down from generation to generation, for example. Crime, gangs, violence, and inner-city neighborhoods have been studied in a manner that ties the concept of subculture to criminal and even violent behavior.

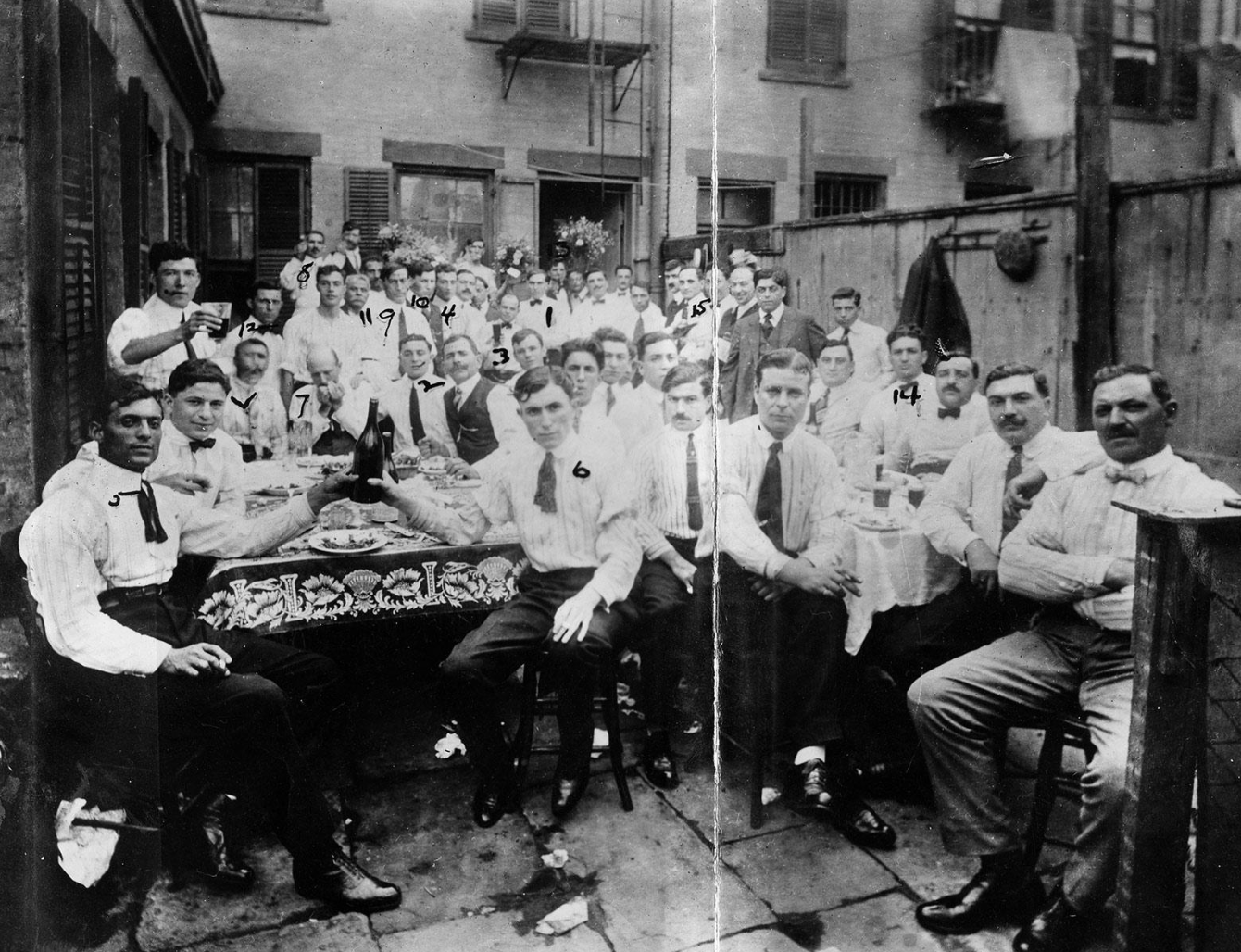

Frederic Thrasher, another sociologist from the famed Chicago School, conducted a classic study in 1927 in which he described gangs as coming together spontaneously at first, then becoming integrated through conflict with other gangs and the surrounding community. The gangs had similar features to formal organizations, such as an identity as a group, stability, commitment, exclusivity, and an internal structure with distinct statuses and roles (Figure 4.19).

Thrasher’s study included 1,313 gangs that each occupied a part of Chicago. He believed that the social conditions in the United States at the end of the 19th century encouraged the development of street gangs. An influx of immigrants filled the inner-city neighborhoods, and they created a more culturally diverse population that was subjected to deteriorating housing, poor employment prospects, and a rapid turnover in the population. The conditions created socially disorganized neighborhoods (remember social disorganization theory) with weak and ineffective social institutions and social control mechanisms. It was this lack of social control that Thrasher believed encouraged youth to discover alternative ways to establish social order, which was accomplished by forming gangs.

If you want to learn more about Gerardo Lopez, a man who grew up in Los Angeles, California, and joined the gang MS-13 at the age of 14. You can watch the video “How I Got Out of MS-13” in the Chapter Resources section.

Subculture of Violence Theory

Marvin Wolfgang and Franco Ferracuti (1982) developed the subculture of violence theory that suggests violence is not expressed in every situation, but rather that individuals are constantly prepared for violence. Specifically, they proposed that no subculture can be totally different from or totally in conflict with the society of which it is a part. They implied that norms of behavior are created in social conditions, social classes, and ethnic and racial groups. Wolfgang (1958) conducted a study on homicide in Philadelphia and discovered evidence consistent with his and Ferracuti’s theory. Forty-three percent of the homicide offenders had been arrested previously for crimes against persons, and about one-fourth of homicide victims had been previously arrested for violent crimes. The conclusion is that there are certain groups in certain areas where there exists a norm that favors the use of violence to deal with conflict, and it is seen as normal in these communities. For some, violence is more common during their youth, but as they become older, they distance themselves from the violence that once may have been common. Reacting to situations with violence is a learned behavior that can be unlearned.

Code of the Streets

In 1999, Elijah Anderson published his findings of a study that looked at Black neighborhoods along Philadelphia’s Germantown Avenue in his book The Code of the Street. Anderson detailed the aspects of the code of the streets, or street culture, that stressed a hyperinflated notion of manhood that centers on the idea of respect. According to Anderson, respect was defined as being treated right or being granted one’s props or the deference an individual deserves. In the code, a man’s sense of worth is determined by the respect he can command in public. How is this respect gained? Anderson found that since they lived in a violent subculture, an individual could not back down from any threat, no matter how serious. Also, since economic and social circumstances limited opportunities for legitimate success, many tried to find alternative ways of making money to provide for their families. One major distinction that Anderson made was between both families and people in the inner-city neighborhoods by dividing them into two different groups: decent families and street families. “Decent families” upheld positive values. Conversely, “street families” were oriented to the values of the streets, which involved displays of physical strength and intellectual prowess that demonstrated their ability to take care of themselves and their families. The code helped achieve success on the streets, but was very detrimental when it came to socially accepted (and legal) success. Violence in society does not generally increase opportunities; rather, it limits opportunities. This makes for a difficult transition for individuals who wish to leave “the life” but don’t have the skills to achieve success in a society where one doesn’t benefit from being street-smart.

Check Your Knowledge

Licenses and Attributions for Understanding Race and Crime: Criminological Theories

Open Content, Original

Figure 4.14. Redlining graphic by Jessica René Peterson, Open Oregon Educational Resources, is licensed under CC BY 4.0.

Figure 4.16. “Neighborhood Home Values Infographic” by Shanell Sanchez and Michaela Willi Hooper is licensed under CC BY 4.0.

Open Content, Shared Previously

“Understanding Race and Crime: Criminological Theories” is adapted from:

- “Theoretical Perspectives in Sociology” and “The History of Sociology” by Tonja R. Conerly, Kathleen Holmes, and Asha Lal Tamang, Intro to Sociology 3e, OpenStax, which is licensed under CC BY 4.0.

- “Sociological Theoretical Perspectives” by Erika Gutierrez, Janét Hund, Shaheen Johnson, Carlos Ramos, Lisette Rodriguez, and Joy Tsuhako, ETH 202: Racial and Ethnic Relations, Long Beach City College, Cerritos College, and Saddleback College, is licensed under CC BY-NC-SA 4.0.

- Introduction to Criminology: An Equity Lens by Jessica René Peterson and Taryn VanderPyl, Open Oregon Educational Resources, licensed under CC BY 4.0.

Modifications by Shanell Sanchez, revised by Jessica René Peterson, licensed under CC BY-NC-SA 4.0, include remixing, expanding, and editing for style.

“Strain Theory” is adapted from 5.2 The Social Structure by Jessica René Peterson and Curt Sobolewski, Introduction to Criminology: An Equity Lens, Open Oregon Educational Resources, which is licensed under CC BY 4.0.

Figure 4.12. “W. E. B Du Bois at the Office of The Crisis, a magazine of the NAACP” is in the Public Domain, courtesy of the New York Public Library.

Figure 4.13. “Unemployed men during the Great Depression” is in the Public Domain.

Figure 4.15. “Home Owners’ Loan Corporation Philadelphia redlining map” is in the Public Domain.

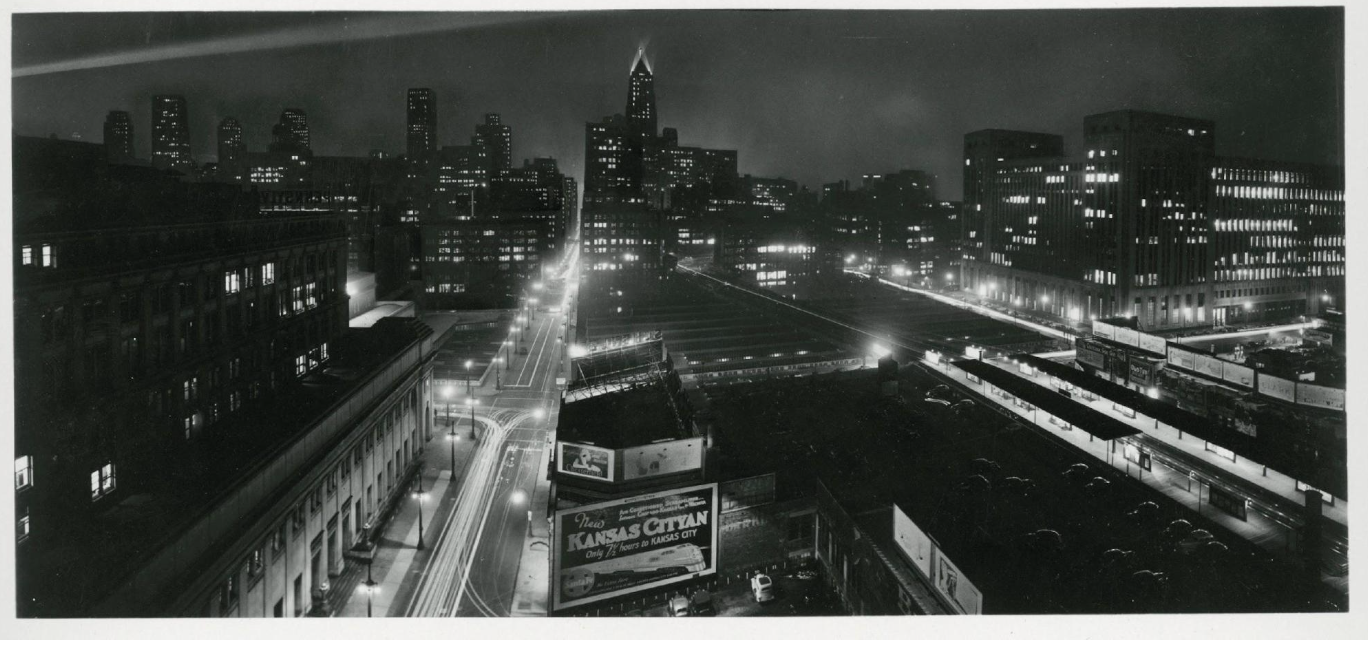

Figure 4.18. Photo of the Chicago 1930s is in the Public Domain.

Figure 4.19. “Navy Street gang” by A stranger is in the Public Domain.

All Rights Reserved Content

Figure 4.17. “Adam Ruins Everything: Why the American Dream Is a Myth” by TruTV is licensed under the Standard YouTube License.

the scientific and systematic study of human relationships, institutions, groups and group interactions, societies, and social interactions, from small and personal groups to large groups

scientific explanations of things happening around us, such as patterns in social behavior, and how certain things are related

a group’s shared practices, values, and beliefs.

a category of people grouped because they share inherited physical characteristics that are identifiable, such as skin color, hair texture, facial features, and stature

a form of prejudice that refers to a set of negative attitudes, beliefs, and judgments about whole categories of people, and about individual members of those categories because of their perceived race and ethnicity.

Black people carry dual notions of how they see themselves, while at the same time negotiating how they are seen through the lens of racial oppression

Merton’s theory that when people face strain, social norms become confused, resulting in a willingness to take alternative routes or use alternative means to get to the goals people want

a group of people living in a defined geographic area that has a common culture

an expansion of strain theory that argues social injustice or inequality may be at the root of strain - not just the search for the American Dream - which includes adolescence and asserts delinquency is a natural reaction to an adolescent’s perception society is stacked against them (Agnew 1992)

theory which argues that four factors—social class, school performance, status frustration, and reaction formation (coping methods)—contribute to the development of delinquency in juveniles (Cohen 1955)

an identifiable subgroup within the larger culture whose values may differ from those present in the dominant group

rules a person must follow during probation

organized action intended to change people’s behavior (Innes 2003).

theory that suggests violence is not expressed in every situation but rather that individuals are constantly prepared for violence (Wolfgang & Ferracuti, 1982)

stressed a hyperinflated notion of manhood that centers on the idea of respect, published by Elijah Anderson in 1999. Also called street culture.