5.3 Police Discretion

Let’s look at a simple scenario: the bulbs in John’s taillights of his car are out. When John passes Officer Ramirez on his way to work, he is pulled over, told to get his taillights fixed, and let go. Later, when John is on his way home from work, he passes by Officer Smith, who pulls John over and writes him a ticket for having broken taillights. John’s infraction did not change, so why did the response from the officers differ?

When we ask Officer Ramirez why he did not write John a ticket, he explains that broken taillights are not that big of a deal, and he only pulled John over as a courtesy to let him know they needed to be fixed. Officer Smith tells us that he wrote John a ticket because broken taillights pose a significant risk to him and other drivers. He explains how broken taillights can increase the chance of accidents and come with severe financial and insurance costs. Although these officers have very different views about the intention behind or severity of broken taillights, both of these officers acted appropriately within their authority. Each officer was utilizing one of the most important components of their job: discretion.

Police discretion is the decision-making power that law enforcement officers possess. In much of their job, police can choose when and how to enforce the law. For example, they may choose whether or not to stop and assist someone, write a ticket, make an arrest, draw a weapon, include certain details in a report, and more. Officers make these types of decisions all day, every day, and frequently in just seconds. They rely on officer training, intuition, critical thinking, creative thinking, self-awareness, and social skills to decide if, when, and how to intervene.

Decades of research show that police consider a multitude of factors when making decisions and using their discretion. Legal factors that police consider consist of things like a person’s prior criminal record or the severity of their crime. Many other traits and circumstances can also impact police discretion, including, but not limited to, agency policy, culture, neighborhood crime rates, suspect socioeconomic status, suspect attitude/demeanor, suspect reputation, officer beliefs, or officer education level. Reliance on extralegal factors like gender, race, or religion can lead to discriminatory use of discretion by officers. The influence of these suspect characteristics on decision-making may be a result of implicit bias or overt prejudice, such as racism, homophobia, transphobia, or xenophobia. While discretion in law enforcement can be beneficial to both individuals and the criminal justice system, it amplifies police power and can also be unequally used and abused.

Implicit Bias and Discrimination

As explained in Chapter 1, everyone can hold implicit biases that are shaped by attitudes, perceptions, experiences, stereotypes, and associations. An example of implicit bias during a police-citizen interaction would include an officer automatically assuming that a man with long hair is a hippie who smokes pot. This implicit bias could creep into the officer’s use of discretion and impact the way the officer interacts with the man or interprets his behavior.

An overt display of racial discrimination in policing might include an officer arresting all of the Black teens at a party and letting the white teens go, even though they were all equally intoxicated. It might also look like an officer only choosing to pull over speeding motorists who were people of color. In many cases, racial or ethnic discrimination in policing can be much more subtle but still observable and harmful.

You might think about police discretion and bias in terms of actions taken by police. Discretion and implicit bias can also result in the absence of action. For example, a police officer could choose not to take life-saving measures to prevent someone’s death if they did not think the person was worthy of saving. The 1921 Tulsa Race Massacre is a controversial example where many accounts suggest that police failed to take action that could have helped Black victims and failed to arrest white perpetrators for their involvement in the assault on property and life. If you are interested in learning more about the events of the Massacre, see the webpage “1921 Tulsa Race Massacre” in the Chapter Resources. A more recent and high-profile example includes officers’ delayed response during the 2022 shooting at Robb Elementary School in Uvalde, Texas. While much of the attention has been on the failure of police leadership with race and ethnicity as only a minor part of the discussion, inaction by all officers involved left a shooter alone in the school to continue his rampage for over an hour (Mendez, 2023). In other words, police inaction grounded in prejudice can be just as or even more detrimental to your well-being.

Activity: Konerak Sinthasomphone: Dahmer’s Youngest Victim

Jeffrey Dahmer is an infamous serial killer who killed 15 men and boys between 1987 and 1991. Most of his victims were Black, Indigenous, Asian, and Latinx boys or men whom he met at gay bars in Milwaukee, Wisconsin. In 1991, a call was made to 911 about a naked boy who had been beaten up and needed help. Two police officers arrived to find a disoriented 14-year-old Laotian boy named Konerak Sinthasomphone with Jeffrey Dahmer. Dahmer told police that Sinthasomphone was his 19-year-old drunk lover, and police left, leaving the boy in Dahmer’s custody. Dahmer soon murdered Sinthasomphone.

As more information about Dahmer’s serial homicides came to light, there was much speculation about the officers’ unwillingness to act and protect the victims, who were all presumed to be gay young men of color.

Consider the following questions:

- How did systemic racism and homophobia influence the police officers’ response to Konerak Sinthasomphone’s case?

- How significant do you think the victims’ marginalized statuses were in prolonging Dahmer’s reign?

- What role do societal biases play in shaping who is perceived as a victim and who is believed in interactions with law enforcement?

- How does media coverage influence public perception of crime victims and perpetrators, particularly when race and sexuality are factors?

Differential Patterns in Police Encounters

Concerns about discriminatory use of discretion have prompted much research in this area, with some mixed results, particularly regarding reasons behind disparities in the use of discretion. However, U.S. crime data and criminological research show patterns of different police behavior and police stops toward different races and ethnicities. For example, Chapter 2 discussed the phenomenon of disproportionate minority contact between police and youth of color. In 2022, researchers used data from over 130 million police traffic stops and found that Black drivers were stopped at disproportionate rates in most counties. Additionally, these disparities were higher in counties that had higher levels of racial prejudice among white community members (Stelter et al., 2022).

People of color are also searched by police at disproportionately higher rates. The Stanford Open Policing Project, a database that tracks vehicle and pedestrian stops by police across the United States since 2015, examined disparities in, and also tested for discrimination in, stops and searches. In almost every jurisdiction they study, Black and Hispanic drivers are searched more often than white drivers. The success rate of those searches is lower for Hispanic drivers, indicating there is likely discrimination in the decision to conduct those searches. Although search success rates for Black drivers are similar to those of white drivers, police have less suspicion about the person and situation when choosing to conduct searches on both Black and Hispanic drivers compared with their white counterparts (Stanford Open Policing Project, n.d.). Similarly, previous research showed that the interaction of age and race was significant, as young Black male drivers were 1.5 times more likely to be searched for discretionary purposes compared to other drivers (Tillyer et al., 2012).

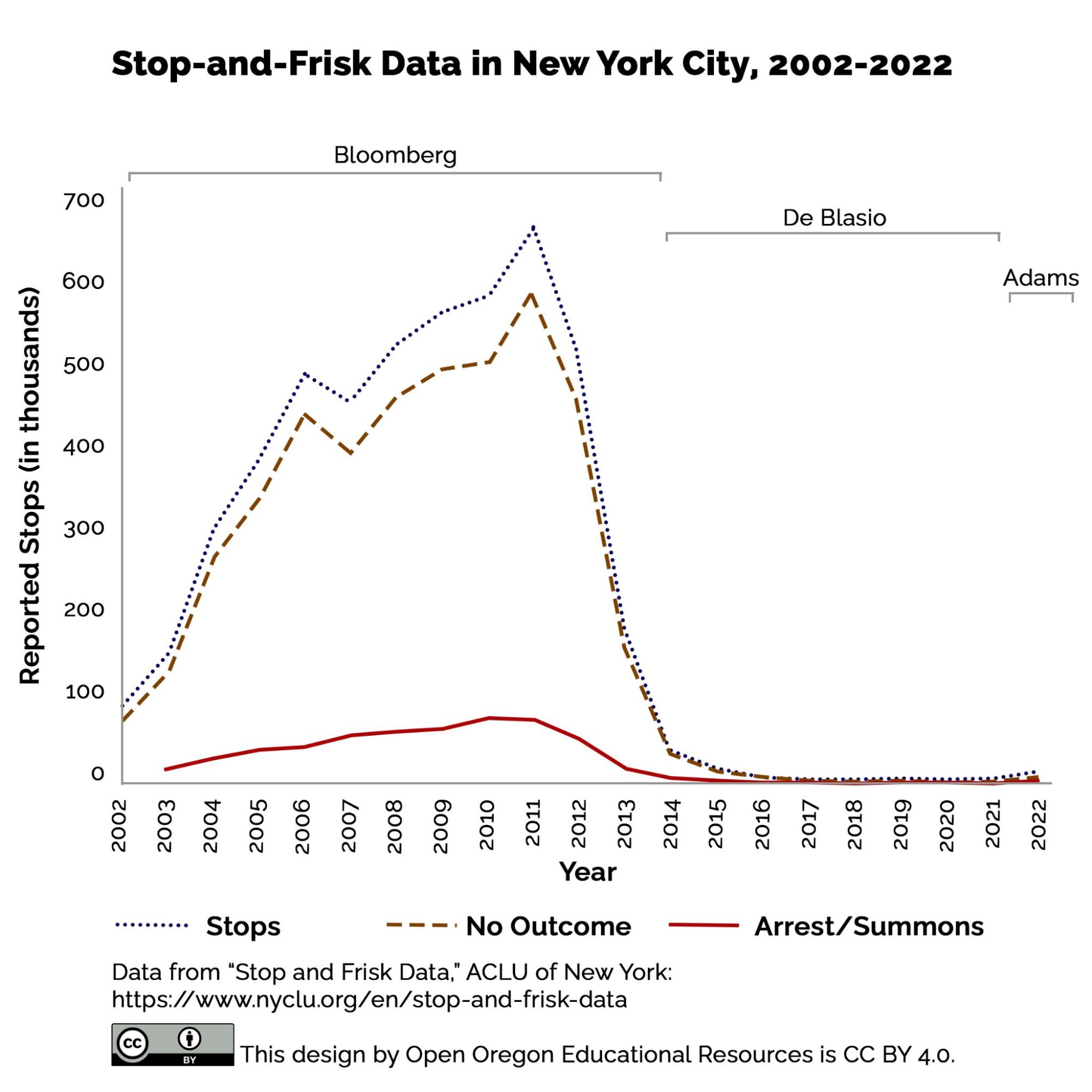

Terry searches, also known as “stop-and-frisks,” are brief pat-downs for weapons intended to protect police officers and the public. Beyond constitutional concerns with Terry searches, some police agencies, such as the NYPD, have used stop-and-frisks in a way that disproportionately targets Black and Latinx individuals. Although the number of these frisks has decreased over the years, disparities in the use of Terry searches have not disappeared. While Black and African American people made up an estimated 23 percent of New York City’s population in 2022, nearly 60 percent of the NYPD’s stops that year were of Black individuals (New York Civil Liberties Union, 2023; U.S. Census Bureau, 2023). The fact that many of these stops and frisks do not produce firearms or result in an arrest raises further questions about their use. See Figure 5.13 for the number of total stops in New York City between 2002 and 2022, compared to the stops that resulted in an arrest or had no outcome.

Finally, there are racial disparities in differential arrest patterns as well. For example, although Black and African American people make up about 14 percent of the total U.S. population, they accounted for 27 percent of arrests made in 2021 (FBI Crime Data Explorer, n.d.). Racial profiling occurs when police use race or ethnicity as a primary or sole factor when choosing to engage with or take enforcement action against someone. It is an abuse of discretion, but not always easy to determine regarding differential patterns in police encounters.

Research on the racial disparities of stops, searches, and arrests supports anecdotes from people of color who face the common experience of “driving while Black.” This phrase has many derivatives, such as “learning while Black” or “walking while Black,” to describe the experiences of Black and Indigenous people of color who feel watched and harassed by police, store clerks, and community members for going about their daily lives. In other words, BIPOC report racially motivated harassment not only by police, but also by members of the public who call on the police without good reason. For example, in 2022, a woman in Seattle was quick to call 911 when she saw a Black man outside of the house he had moved into with his white partner three weeks prior. She did not believe him when he explained that he lived there and asked to see his lease as proof (Yoon-Hendricks, 2022). Such behavior that unnecessarily involves police and brings the risk of police violence has been dubbed by some as “white caller crime” (McNamarah, 2019).

It is important to keep a couple of important methodological ideas in mind when evaluating disparities in police interactions and arrests. First, research and government databases fail to accurately differentiate between racial and ethnic minorities. For example, studies might just compare arrests of white versus non-white people, even though “non-white” includes a lot of different races and ethnicities. Second, researchers cannot isolate factors like race in a lab to study the impact of each independently. Many factors come together to influence a police officer’s perception of who someone is and that person’s worthiness of leniency or a “by-the-book” response (Maynard-Moody and Musheno, 2003). However, findings such as those mentioned above speak to the reliance on race and ethnicity as a piece of officers’ overall calculations.

Over-Policing and Under-Policing

Some people argue that a higher rate of encounters between police and BIPOC is due to a higher rate of offending among that population. However, research shows that racial and ethnic differences in offending behavior do not account for all of these encounters. For many offenses, such as drug use, offending rates are similar across racial divides and when comparing Black and white populations (Center for Behavioral Health Statistics and Quality, 2021). However, an increased presence of police in BIPOC communities has been linked to racial disparities in police encounters and arrests.

Practices such as broken windows and hot spot policing have increased the concentration of police in BIPOC communities. This led to the over-enforcement of laws against racial and ethnic minorities. Over-policing of marginalized populations can lead to a variety of negative outcomes. Those who experience aggressive or continued stops by police can suffer psychological distress, school disruptions for youth, and fear or resentment of police that erodes trust (Crifasi et al., 2022). On the other hand, under-policing of marginalized communities can also be detrimental to residents’ safety. BIPOC residents, such as the interviewee below, express frustration with the ironic lack of police presence when they need help:

If somebody broke into my house I would go grab a gun and start shooting first before I called the police…the police don’t respond to a gun call…take ’em five hours to get there for that, but you tell them somebody on the corner selling a bag of weed, here they come 50 cars deep. But you tell them somebody is lying there dying, take the cops four hours to get there. — Interviewee from the video “Street Codes – Code of the Streets, Elijah Anderson,” 2015

Preferences on police patrol in one’s community are not the same among all Americans. In a 2020 survey, 51 percent of Americans in fragile communities, defined as areas with high poverty rates, low rates of postsecondary education, and a lack of opportunities, wanted police to spend more time in their communities, with only 6 percent saying they wanted police to spend less time in their communities (Council on Criminal Justice, 2020). In the same year, 61 percent of Black adults, 59 percent of Hispanic adults, and 63 percent of Asian adults across the entire nation wanted police to spend the same amount of time in their area, compared to 71 percent of white adults (Saad, 2020; see figure 5.14). White people were less likely to want a change in police presence. These findings may speak to the conflict around how police spend their time in different communities.

| Group | Prefer that police spend more time in your area | Prefer that police spend the same amount of time in your area | Prefer that police spend less time in your area |

|---|---|---|---|

| Black Americans | 20% | 61% | 19% |

| White Americans | 17% | 71% | 12% |

| Hispanic Americans | 24% | 59% | 17% |

| Asian Americans | 9% | 63% | 28% |

| U.S. Adults | 19% | 67% | 14% |

Corruption

Police corruption can occur at the individual, unit, agency, or even systemic levels. Although corruption may be primarily driven by the desire for power or profit, marginalized groups and economically challenged communities are more vulnerable and easily targeted. After the fact, police officers are often given the benefit of the doubt when stories are compared. Two prime examples of police corruption targeting marginalized communities can be seen in Jon Burge and his Midnight Crew and the Gun Trace Task Force in Baltimore, Maryland.

Former police commander Jon Burge of the Chicago Police and his Midnight Crew of white detectives tortured over 100 Black people across three decades. From the 1970s until 1990, Burge oversaw forced false confessions, racist verbal abuse, sexual assault, mock lynchings and executions, shocking, burning, and beating of body parts, and the handing down of death row sentences against innocent people (Mogul, n.d.; Stanford Libraries, n.d.). Although he was convicted of obstruction of justice and perjury for lying, he was never held criminally responsible for the physical, sexual, or psychological torture of his victims, most of whom were people of color. If you are interested in learning more about Jon Burge and the Midnight Crew, you can read more on the website Chicago Police Torture Archive in the Chapter Resources.

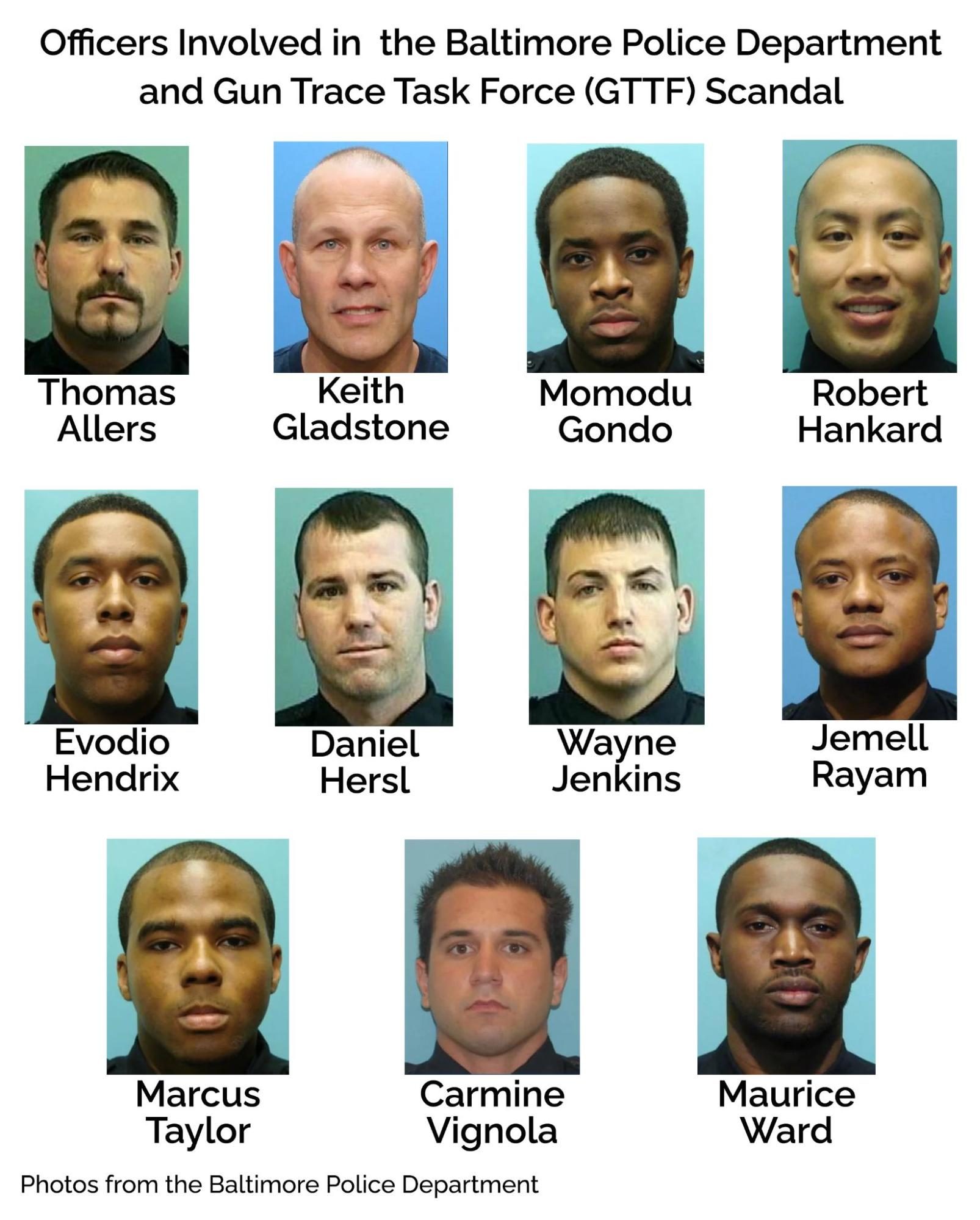

After experiencing high rates of gun violence, the police department in Baltimore, Maryland, created the Gun Trace Task Force in the early 2000s. By 2015, concerns about the behavior of officers in the unit were rising. In 2017, eight officers were arrested and charged with racketeering, robbery, extortion, and overtime fraud that took place between 2015 and 2016. In a community of color that already had a strained relationship with police due to the death of Freddie Gray in police custody, officers involved with the Gun Trace Task Force exploited and profited from the residents. Officers assaulted and violated residents’ constitutional rights, robbed drug dealers, and planted guns and evidence on innocent people (Bromwich et al., 2022). As of January 2022, 13 officers have been charged with crimes associated with the scandal, and the city of Baltimore has paid over $22 million in settlements related to the Gun Trace Task Force (Skene, 2023). If you are interested in learning more about the investigation of the corruption in Baltimore and the accountability measures that were taken, you can read more on the website Gun Trace Task Force Investigation in the Chapter Resources.

Corruption at these levels, which include exploitation and abuse of the community, significantly decreases police legitimacy – the concept that refers to the view of law enforcement as a legitimate and respected authority – as residents fear, distrust, resent, and no longer respect the authority of the police. Beyond the emotional and psychological toll on the residents, such a negative relationship also impacts the criminal justice system when cooperation and collaboration between police and the community dissolve. It is often debated whether or not police corruption is individualistic (i.e., “bad apples”) or systemic (i.e., “rotten barrel”). Examining how the history and development of policing and laws have impacted the field’s culture and practices can shed light on this discourse.

Check Your Knowledge

Licenses and Attributions for Police Discretion

Open Content, Original

“Police Discretion” by Jessica René Peterson is licensed under CC BY 4.0.

Open Content, Shared Previously

The four questions in “Activity: Konerak Sinthasomphone: Dahmer’s Youngest Victim” were developed in collaboration with ChatGPT by Jessica René Peterson using the “Police Discretion” chapter, revised by Jessica René Peterson, and are licensed under CC BY 4.0.

Figure 5.13. “Stop-and-Frisk Over Time” by Open Oregon Educational Resources is licensed under CC BY 4.0. Data from “Stop-and-Frisk Data” by NYCLU.

All Rights Reserved Content

Figure 5.12. Photo of Konerak Sinthasomphone is included under fair use.

Figure 5.14. “Preference for Amount of Time Police Spend in Your Area” from “Black Americans Want Police to Retain Local Presence” by Lisa Saad, Gallup, included under fair use.

Figure 5.15, left. Photo of Andrew Wilson by Joey L. Mogul in “The Struggle for Reparations in the Burge Torture Cases: The Grassroots Struggle That Could,” in “Legal History,” The People’s Law Office’s Archive, Chicago Police Torture Archive. Included under fair use.

Figure 5.15, right. Cover of the Chicago Tribune (January 22, 2011) by Tribune Publishing, Chicago Police Torture Archive, is included under fair use.

Figure 5.16. Gun Trace Task Force photos © Baltimore Police Department are included under fair use.

decision-making power that law enforcement officers possess for when and how to enforce the law

a group’s shared practices, values, and beliefs.

a category of people grouped because they share inherited physical characteristics that are identifiable, such as skin color, hair texture, facial features, and stature

an individual attitude based on inflexible and irrational generalizations about a group of people and literally means “judging before.”

a form of prejudice that refers to a set of negative attitudes, beliefs, and judgments about whole categories of people, and about individual members of those categories because of their perceived race and ethnicity.

widely held beliefs or assumptions about a group of people based on perceived characteristics.

the unfair treatment of marginalized groups, resulting from the implementation of biases, and often reinforced by existing social processes that disadvantage racial minorities

shared social, cultural, and historical experiences of people from common national or regional backgrounds that make subgroups of a population different

refers to how racism is embedded in the fabric of society and how institutional processes are used to maintain systematic discrimination through the complex interactions of large scale societal systems, practices, ideologies, and programs that produce and perpetuate inequities for racial minorities. Also referred to as institutional or structural racism.

overrepresentation of ethnic, racial, and linguistic minority youth in the juvenile system

when police use race or ethnicity as a primary or sole factor when choosing to engage with or take enforcement action against someone

stressed a hyperinflated notion of manhood that centers on the idea of respect, published by Elijah Anderson in 1999. Also called street culture.

the degree to which society or a community views law enforcement as a legitimate and respected authority