5.4 Police Training and Culture

This section will highlight some key ways in which the discussion of race and ethnicity intersects with police training and culture. First, it is important to consider the way that the history and evolution of policing have impacted the current demographic makeup and culture of the profession. This includes a discussion of diversity in policing as well as the policing of diverse communities. Next, a few initiatives for improving police practices and relations with communities of color will be addressed.

Police Officer Demographics

Racial and ethnic diversity within the field of policing is historically and currently lacking. white men were really the only people filling the role of police until the late 1800s and early 1900s. Even as policing professionalized and diversified, newcomers were not initially given the same role. For example, when Black men started joining the police force, particularly in Southern states, they were not given the same duties or privileges as their white counterparts. They were tasked with policing Black communities and did not have the power to arrest white individuals. Oftentimes, they wore separate uniforms. Similarly, women of all races and ethnicities had a much different job than male police officers. Women did not have typical patrol duties until the late 1960s when Elizabeth Coffal Robinson and Betty Blankenship became the first sworn female police officers with duties, equipment, and privileges that equaled those of men (National Law Enforcement Officers Memorial Fund, 2023). However, Georgia Robinson is largely considered the first Black female police officer who was appointed to the Los Angeles Police Department in 1916 (The Community Policing Dispatch, 2017).

Although Indigenous people practiced forms of social order maintenance within their communities (MacLeod, 1937) – even though their practices of policing differed from those of early settler America – none were technically considered American police officers until 1924. That year, the Indian Citizenship Act was passed and granted citizenship to all Native Americans who had been born in the United States (Lomawaima, 2013). In other words, even though some Indigenous peoples were engaging in their forms of policing, their practices were inherently unrecognized in American policing history since they were not considered citizens of the United States.

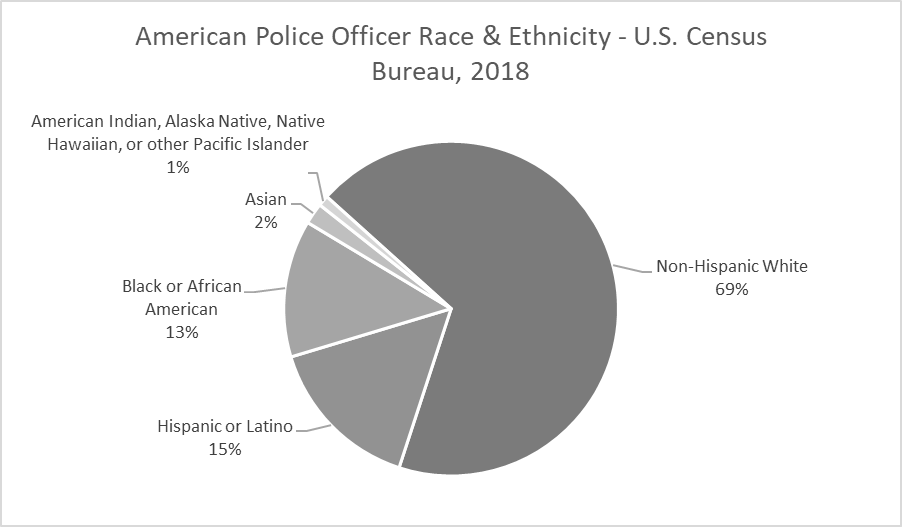

Today, the policing profession in the United States is still dominated by white men. Nationally, women make up about 13 percent of the total American police force, and approximately 68 percent of the force is non-Hispanic white. Although the demographics of police differ by state, Figure 5.18 provides a national profile of officer race and ethnicity as of 2018. The evolution of policing in the United States, as well as the racial, ethnic, and gender composition of the law enforcement profession, has had an impact on the occupational culture in policing.

Police Culture and Representation

The occupational culture in policing has roots in patriarchy and white supremacism. Many scholars, particularly those who have immersed themselves in police agencies through ride-alongs, have documented police officers’ use of derogatory slang toward racial and ethnic minorities (Skolnick, 2008). Investigations have exposed police officers with ties to hate groups such as the KKK. The Department of Justice and Federal Bureau of Investigation even reported concerns about the infiltration of white supremacy in American law enforcement in recent years (German, 2020).

Female and non-white police officers have expressed feelings of rejection, objectification, or being unwanted, and experienced subtle and overt racism or sexism in their agency or profession. They also face a variety of obstacles in their careers, such as unfair evaluations, disciplinary action, obstacles to promotions and career advancements, and a variety of other workplace problems (Hassell and Brandl, 2009). Women of color can experience compounded marginalization on the job as members of both a gender and racial minority group (Yu, 2023). These feelings can be linked to tokenism, or the concept in which inclusion of underrepresented groups is only symbolic and no real effort is made to integrate all of the members.

In 2015, the Department of Justice’s Civil Rights Division and the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission launched a research initiative called “Advancing Diversity in Law Enforcement.” The goal was to promote the recruitment, hiring, retaining, and promotion of a police workforce that would reflect the communities served (U.S. Department of Justice Equal Employment Opportunity Commission, 2016). Since then, many police agencies have developed hiring strategies aimed at increasing diversity on the force and improving comfort among officers who are from historically marginalized groups. For example, as part of their Affirmative Action Plan, the Oregon State Police sent staff into four Historically Black Colleges and Universities to provide guest lectures and recruit potential police applicants from underrepresented populations (Oregon State Police, 2019). Plans like these have increased diversity in applicant pools and new hire cohorts in American police agencies over the past several decades.

However, simply increasing demographic diversity in the profession is not enough. Some argue that social division within law enforcement as a result of increased diversity on the force – of which there is some evidence (Sklansky, 2006) – has been detrimental to police practices and solidarity. Diversification itself is not the issue; rather, the issue is a culture that holds onto its exclusionary and unwelcoming roots. As some officers of color conform to the existing police culture and exhibit similar problematic behaviors as their white counterparts (Skolnick, 2008), more research on police culture and how to make it more inclusive and cohesive is necessary. If you are interested in learning more about diversity efforts in policing, listen to the episode of the Reducing Crime podcast with the Deputy Commissioner of Equity and Inclusion for the New York City Police Department (available in the Chapter Resources).

Initiatives for Working with Diverse Populations

Beyond the comfort of diverse populations working on the force, there have also been initiatives to improve police interactions with diverse community members. Hiring officers who are members of underserved groups is one strategy since this can increase awareness and understanding of marginalized community members. Many metropolitan agencies have gone a step further. Some agencies have created liaison roles based on their community needs and demographics. For example, the police department in Columbus, Ohio, now has Diversity and Inclusion Liaison Officers who have cultural competence and understanding of issues that impact the LGBTQIA+ community, African American population, and New American population in Columbus. The liaisons maintain their patrol, but also engage community members and attend community meetings (City of Columbus, 2023). Some agencies in highly diverse areas prioritize and incentivize certification in multiple languages to accommodate the array of spoken languages. At the Metropolitan Police Department in Washington, D.C., they currently have officers who speak at least 37 different languages (Metropolitan Police Department, n.d.).

Targeted programs and strategies are often localized. Recently, there has been a large push for more standardized and required implicit bias training. The hope is that if an officer is aware of their own implicit bias, they may be able to adjust their response to avoid unequal treatment of or discrimination against a community member. Many states have implemented such training for all of their officers. As of January 2023, all police officers in Oregon are required to complete three hours of equity training during every three-year cycle of their maintenance training to keep their police officer certification. However, although the Department of Public Safety Standards and Training provides multiple relevant topic examples, only one of the four concepts below must be covered in the training to meet the requirements of the law (Yutzie, 2022):

1. Increasing awareness and understanding of diverse identities, thoughts, and experiences.

2. Strategies to mitigate disparate outcomes.

3. Improving public trust and confidence.

4. Diversity, equity, and inclusion in the workplace.

Research on the impact of implicit bias training is in the early stages. The goal is to teach officers how to recognize their own biases and ultimately learn how to prevent those biases from impacting their job and interactions with citizens. A 2023 study that surveyed thousands of officers who participated in implicit bias training did not have promising results for long-term impact. They found that the immediate increase in knowledge and concern about bias started to decrease after about a month and did not result in actual sustained behavioral change. The researchers suggest that different strategies for training implementation and cultural shifts might be necessary to make this training more effective (Lai and Lisnek, 2023). We can conclude that the solution is not easy. Just as increasing diversity in the police workforce is more complex than simply hiring more non-white officers, providing training on bias and equity for police does not solely fix the problem of discrimination without application and integration of the material.

Check Your Knowledge

Licenses and Attributions for Police Training and Culture

Open Content, Original

“Police Training and Culture” by Jessica René Peterson is licensed under CC BY 4.0.

Figure 5.18. “The policing profession still largely comprises white male officers” by Jessica René Peterson is licensed under CC BY 4.0. Data from U.S. Census Bureau, 2018.

Open Content, Shared Previously

Figure 5.17. Georgia Ann Robinson by unknown is in the Public Domain.

a category of people grouped because they share inherited physical characteristics that are identifiable, such as skin color, hair texture, facial features, and stature

shared social, cultural, and historical experiences of people from common national or regional backgrounds that make subgroups of a population different

a group’s shared practices, values, and beliefs.

the racist belief that white people are superior to people of other races and ethnicities

a form of prejudice that refers to a set of negative attitudes, beliefs, and judgments about whole categories of people, and about individual members of those categories because of their perceived race and ethnicity.

the practice of including underrepresented groups on a symbolic level only, with no real effort made to integrate all of the members

the unfair treatment of marginalized groups, resulting from the implementation of biases, and often reinforced by existing social processes that disadvantage racial minorities