5.5 Current Events and Trends

Issues in modern American policing, such as technology and equipment used by police, the militarization of police since 9/11, training and practices such as use of force or no-knock warrants, recruitment and retention on the force, police and public relations, and more, are often found in public and political discourse. We cannot cover all of these issues here, but we will discuss some of the most relevant and significant ones in 21st-century policing, including public perceptions of police, excessive force and police brutality, movements to reform, defund, or abolish police, and police accountability.

Public Perceptions of Police

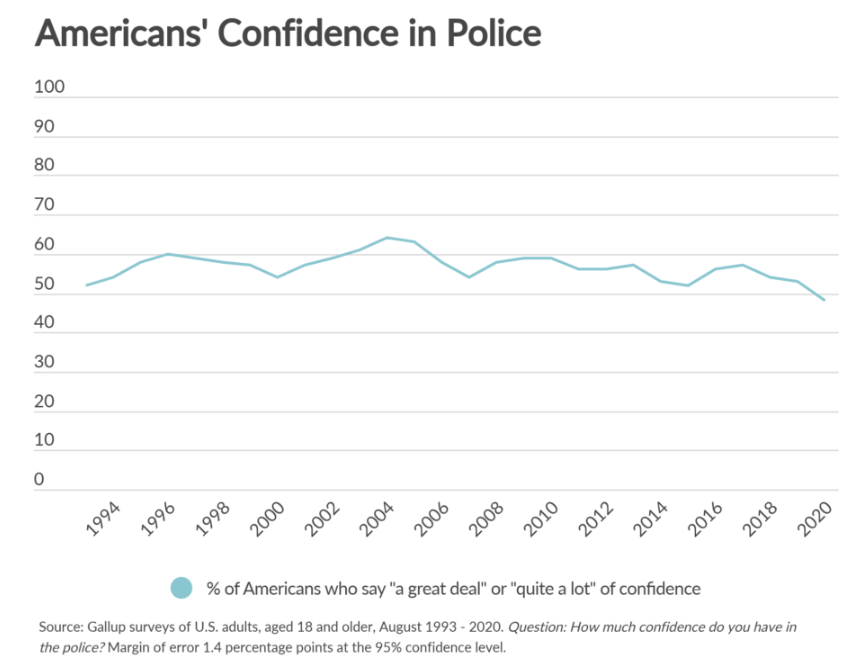

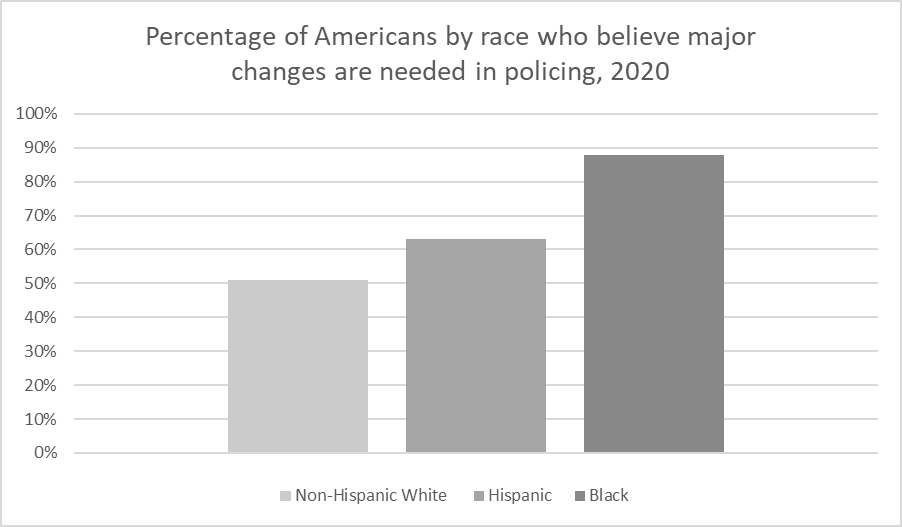

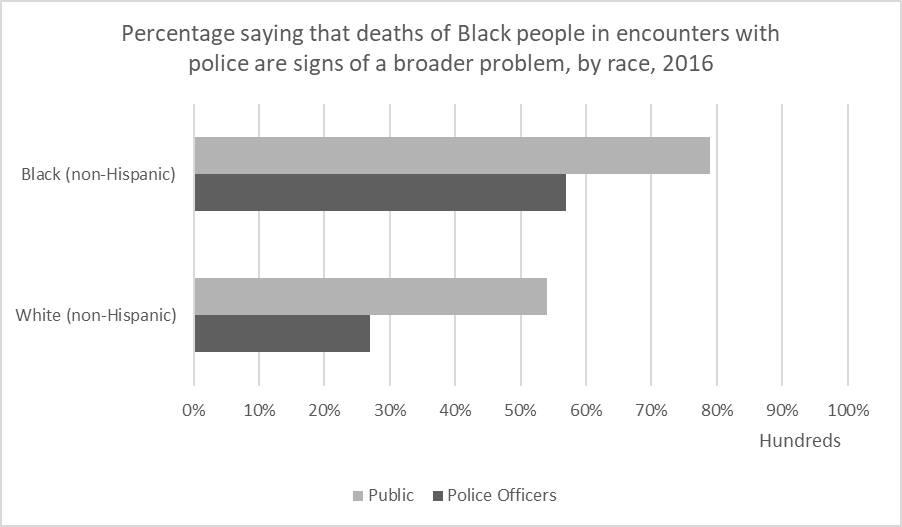

Since 1993, adults in the United States have had relatively stable overall confidence in the police, with generally more than 50 percent of the population reporting “quite a lot” or “a great deal” of confidence in law enforcement (see figure 5.19; Council on Criminal Justice, 2020). However, not only has overall confidence dropped in recent years, but specific questions about policing and racial differences in answers provide a different picture of police confidence. A significant percentage of Black and Hispanic Americans believe major changes are needed in policing, while only just over half of white Americans feel the same way (see figure 5.20; Council on Criminal Justice, 2020). Additionally, police and public perceptions of fatal encounters between police and the Black community differ by race. Not only does the public largely view these incidents as indicative of larger racial justice problems rather than isolated events, but Black citizens and officers are more likely to see these incidents as part of a broader issue between police and the Black community (see figure 5.21; Morin et al., 2017).

Documented experiences of BIPOC populations with police show that disrespect and verbal abuse, including racial abuse, are still prevalent (Ekins, 2016; Council on Criminal Justice, 2020; Neugebauer, 1999). Disrespect, physical or verbal abuse, and unfair treatment erode trust in police and impact police legitimacy. Fair treatment and transparency from the police lead to better cooperation, trust, and collaboration between police and community members.

New forms of media – particularly social media platforms – have changed the amount of access we have and the ways we access information about police. Police body camera footage and live streams from witnesses of police-citizen interactions are widely shared across TV programs and all corners of the internet. Many scholars argue that the changes in technology and media have given us a glimpse into a world from which we were previously barred. Are we simply seeing the discrimination in policing that has always existed, or are these incidents changing? Regardless, such photos and videos have captured incidents of police brutality and excessive use of force that have sparked debate and social justice movements.

Excessive Force and Police Brutality

The use of force is considered a justified part of the policing job under certain circumstances. Excessive force, on the other hand, is the unjustified use of force that goes beyond necessity. We might not all agree on what counts as justified, reasonable, or necessary, but many cases in the past few decades have brought these questions to the forefront.

In 2021, 17 percent of the reported use-of-force incidents involved the discharge of a firearm, with 33 percent of the total use-of-force incidents resulting in death and approximately 50 percent resulting in serious bodily injury (FBI, 2022). Although police shootings and the use of firearms draw increased scrutiny from the public, other police practices can also cause severe injury or death. For example, “air chokes” and “carotid” or “blood chokes” are two forms of chokeholds used to prevent a person from breathing or interrupt the flow of oxygenated blood to the brain, respectively. These actions can cause a suspect to fall unconscious or lead to death if applied incorrectly or for an extended period, especially if the person has pre-existing health problems. Eric Garner is a prime example; even though the NYPD banned the practice, officers placed Eric in a chokehold that led to breathing complications and cardiac arrest (Butler, 2017; Gardner and Al-Shareffi, 2022).

Available data shows that Black and Hispanic/Latinx people are twice as likely to be threatened with force or have force used against them when contacted by police. Additionally, compared to the white non-Hispanic population, Black people are almost five times more likely to need medical care for injuries sustained at the hands of police and are more likely to be killed (Law Enforcement Epidemiology Project, n.d.).

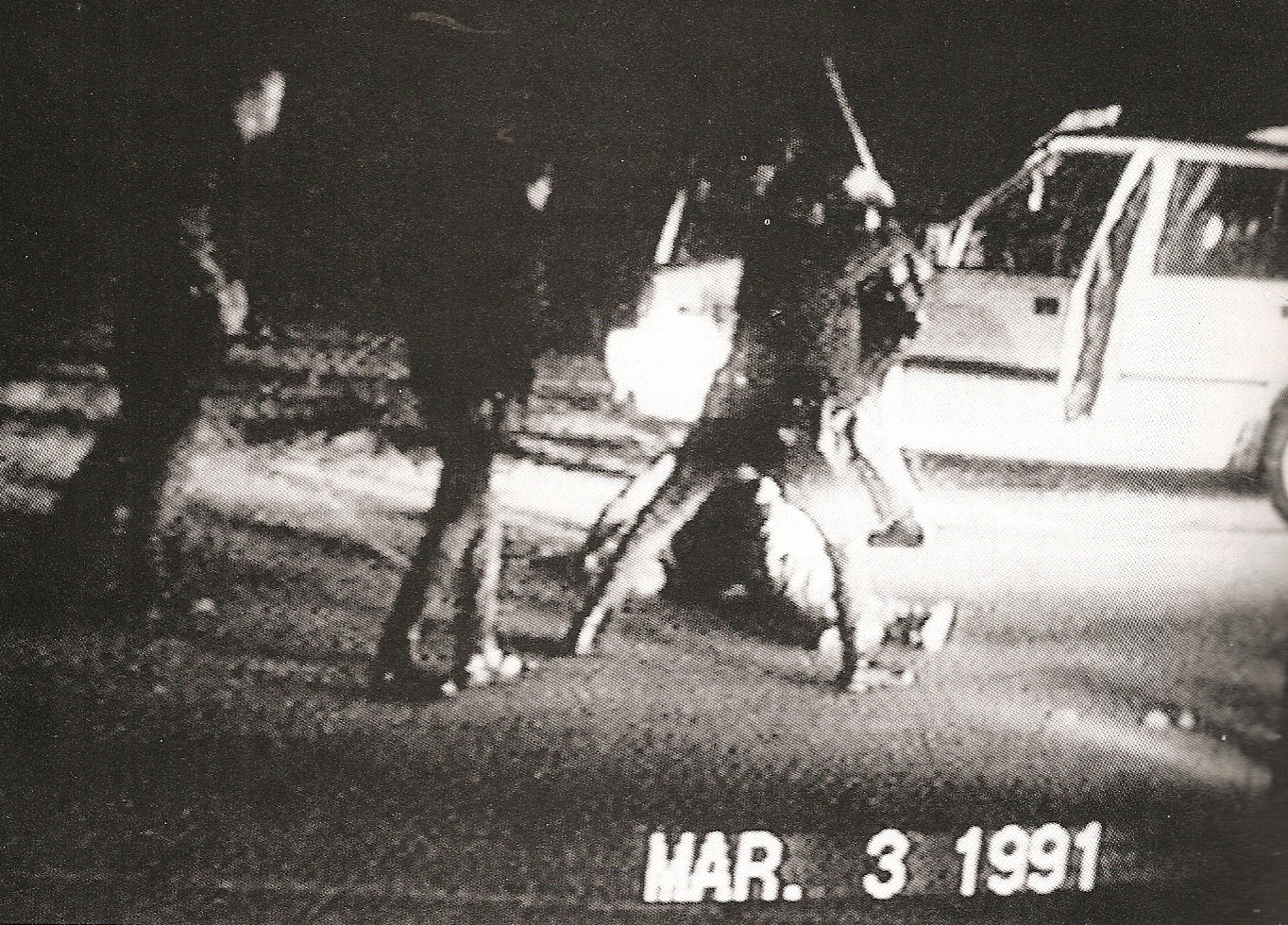

Police brutality and disproportionality in force used against people of color are not new in American history. In 1991, Rodney King was repeatedly kicked and beaten with a baton by officers with the Los Angeles Police Department after a brief vehicle pursuit. The beating was captured on video by a bystander and gained widespread publicity on TV news channels, which led to public discourse and protests about police brutality (Jacobs, 1996). Additionally, much of the current climate around policing can be traced back to 2014, after the police killing of Michael Brown in Ferguson, Missouri. Although there was debate over the details of the case that ultimately failed to indict the officer involved, the event put a spotlight on issues of police brutality, racism, and training. It also launched the Black Lives Matter movement in America. Sometimes referred to as “post-Ferguson policing,” the time since has been characterized by concerns over what policing should look like in the United States.

In the 21st century, high-profile events in which men and women of color have been severely injured or killed by police have prompted new and continued social justice movements, and public and political discussions of police reform. A non-exhaustive list of some such cases is included in the Learn More section below. Although many incidents involve white police officers, an officer’s race may be less significant than the occupation itself. Accordingly, many reform advocates emphasize policy changes that address police practices over diversity efforts. The federal government recently placed explicit restrictions on chokehold restraints and “no-knock” entries when police are serving warrants due, in part, to their disproportionate use against people of color. Some state and local agencies have adopted similar policies as well.

Learn More: List of High-Profile Fatalities Involving Police and the Black Community, 2010–Present*

Investigators with NPR found that approximately 75 percent of police officers who fatally shot people of color since 2015 were white. Although most officers do not become involved in shootings throughout their careers, several of the officers who did fatally shoot someone were involved in multiple deadly shootings without consequences (Thompson, 2021). Figure 5.24 – while not exhaustive by any means – highlights some of the high-profile fatalities of Black individuals by police since 2010. Additionally, if you are interested in learning more, you can view the website Say Their Names: Green Library Exhibit Supporting the Black Lives Matter Movement in the Chapter Resources.

| Name of Victim | Year | Brief Description of Incident |

|---|---|---|

| Eric Garner | 2014 | 43-year-old Black man placed into a banned chokehold by a police officer during an arrest for illegally selling cigarettes in New York |

| Michael Brown | 2014 | 18-year-old Black man shot by police officer after being stopped on the street in Missouri |

| Tamir Rice | 2014 | A 12-year-old Black boy holding a toy gun was shot by a police officer in Ohio while responding to a call |

| Freddie Gray | 2015 | 25-year-old Black man who was aggressively arrested by police officers in Maryland and improperly secured during transportation, which led to a coma |

| Sandra Bland | 2015 | 28-year-old Black woman who was arrested by a police officer in Texas for a minor traffic violation and was later found hanging in her jail cell |

| Alton Sterling | 2016 | 37-year-old Black man shot by two police officers in Louisiana while responding to a call of illegally selling CDs and waving a gun |

| Philando Castile | 2016 | 32-year-old Black man shot by a police officer during a traffic stop in Minnesota |

| Emantic Fitzgerald Bradford Jr. | 2018 | 21-year-old Black man shot by a police officer at an Alabama mall on Thanksgiving Day when he drew a weapon in defense against a shooter |

| Jemel Roberson | 2018 | A 26-year-old Black man was shot by a police officer in Illinois while working as a security guard and pointing his weapon at a gunman |

| Atatiana Jefferson | 2019 | A 28-year-old Black woman was shot inside her home while playing games with her nephew by a police officer in Texas |

| Breonna Taylor | 2020 | 26-year-old Black woman shot by police during a raid on her apartment in Kentucky |

| George Floyd | 2020 | 46-year-old Black man killed when a police officer kneeled on his neck during an arrest in Minnesota for theft |

| Tyre Nichols | 2023 | 29-year-old Black man beaten by police officers in Tennessee after being stopped for an alleged traffic violation |

The most impactful event in policing since Ferguson is the murder of George Floyd. In May of 2020, George Floyd was murdered by Minneapolis, Minnesota police officer, Derrick Chauvin. During an arrest for Floyd’s alleged theft of $20, Chauvin kneeled on Floyd’s neck for over nine minutes, as seen in Figure 5.25. Floyd repeatedly stated that he could not breathe until he died. Most of you are probably aware of George Floyd, but you may be less familiar with the broader impact of his murder.

Many of the recent efforts discussed in this chapter have been fast-tracked since Floyd’s death. Policing is in an era of change, and the very role of law enforcement is under evaluation. Negative community-police relations and the inability of many police agencies to attract applicants have reached levels that increase concern over the future of policing. Notably, Floyd’s death has had an impact beyond the United States, too. For example, police in New Zealand are largely unarmed, although they have special units called Armed Offenders Squads that can respond to those who are threatening or using firearms. Residents of the country have recently expressed concerns over what they refer to as the “Americanization” of their police force and fear that the push to arm more of their police would lead to increased disproportionate use of force against their Māori and Pacific Islander populations (Warner and Antolini, 2020). Further, protests against police violence and calls for change in other countries have invoked the name of Floyd. Policing practices in the United States can have impacts across the globe.

Reform, Defund, or Abolish?

As a profession in the United States, policing has been through at least three separately defined eras that were each characterized by different challenges. However, many of the concerns and changes in law enforcement throughout the 21st century have been on the public’s mind like never before. The concept of police reform is not new. The concepts of defunding or abolishing police are not new either. To discuss these topics, it is very important to define the differences between them.

Reform broadly refers to change. Such change can take many shapes, but generally assumes that the core structure of the institution is sound and that specific practices or strategies could improve policing outcomes. For example, four months after Michael Brown was killed in 2014, President Obama issued an Executive Order establishing a Task Force on 21st Century Policing. The task force provided many areas of suggested reform, prompting many of the changes in policing since their report was published. The suggestions for change fit into six broad pillars:

- Building trust and legitimacy

- Policy and oversight

- Technology and social media

- Community policing and crime reduction

- Training and education

- Officer wellness and safety

While reform may include budgetary changes, defunding requires changes (i.e., decreases) to the budget for police agencies and generally calls for more substantive changes to the foundation of policing. Often, the defund approach is simultaneously accompanied by reallocation of funds and duties elsewhere. For example, in 2020, the city council in Austin, Texas, voted to cut $150 million from the police budget and redistribute those funds to social services and alternative public safety programs such as violence prevention courses and food or abortion access programs (Venkataramanan, 2020).

Abolition, on the other hand, calls for the complete eradication of the institution of policing. Supporters of abolishing the police often propose that police duties, such as responding to mental health crises, could be addressed by other non-law-enforcement entities. Movements on these efforts are primarily confined to reform and defunding, with less widespread public and political support for police abolition. A current example of major shifts in police response includes the establishment of Crisis Intervention Teams or Co-Responders. Learn about one of the most notable and long-standing crisis assistance programs, CAHOOTS, located in Eugene, Oregon, in the Chapter Resources.

Police Accountability

Regardless of which camp you identify with regarding the reform, defunding, or abolition of police, one area of concern for most is that of police accountability. In other words, what happens when a police officer or agency violates someone’s rights or engages in misconduct? Accountability for police wrongdoing can take place at the individual, agency, institutional, or legal levels. Many times, survivors or victims’ families sue the involved cities. However, changes in behavior and practices do not always occur after poor police conduct. Two measures that have been under increased scrutiny lately include consent decrees and qualified immunity.

A consent decree is an agreement between a court and a police agency or other involved parties. It involves mandates, supervision, and enforcement by the court to make sure that the involved parties are following the plan to improve performance or correct identified wrongs. For example, a police department that comes under investigation because its officers continually violate civil rights or the department exhibits signs of systemic dysfunction may enter a consent decree. It is common for high-profile cases to initiate this process. Qualified immunity, on the other hand, is a legal doctrine that protects government officials from constitutional rights violation lawsuits. In other words, it shields government actors – including police officers – from personal consequences of actions taken as part of their work duties unless those actions violate “clearly established law.”

Some accountability measures were eventually taken in both the Burge and Midnight Crew cases and the Baltimore Gun Trace Task Force mentioned earlier in the chapter, but it took a long time for those to come to fruition. The City Council of Chicago approved reparations for survivors of police torture in 2015, and two years later, the Chicago Police Department agreed to a consent decree. Accountability efforts and lawsuit settlements regarding the Baltimore case are still ongoing. However, in a case like Onree Norris’s, where a no-knock warrant went wrong, qualified immunity led to his lawsuit being thrown out. The lack of accountability and satisfactory outcomes of these efforts has led to calls for change.

Activity: Dontre Hamilton and the Milwaukee Police Department

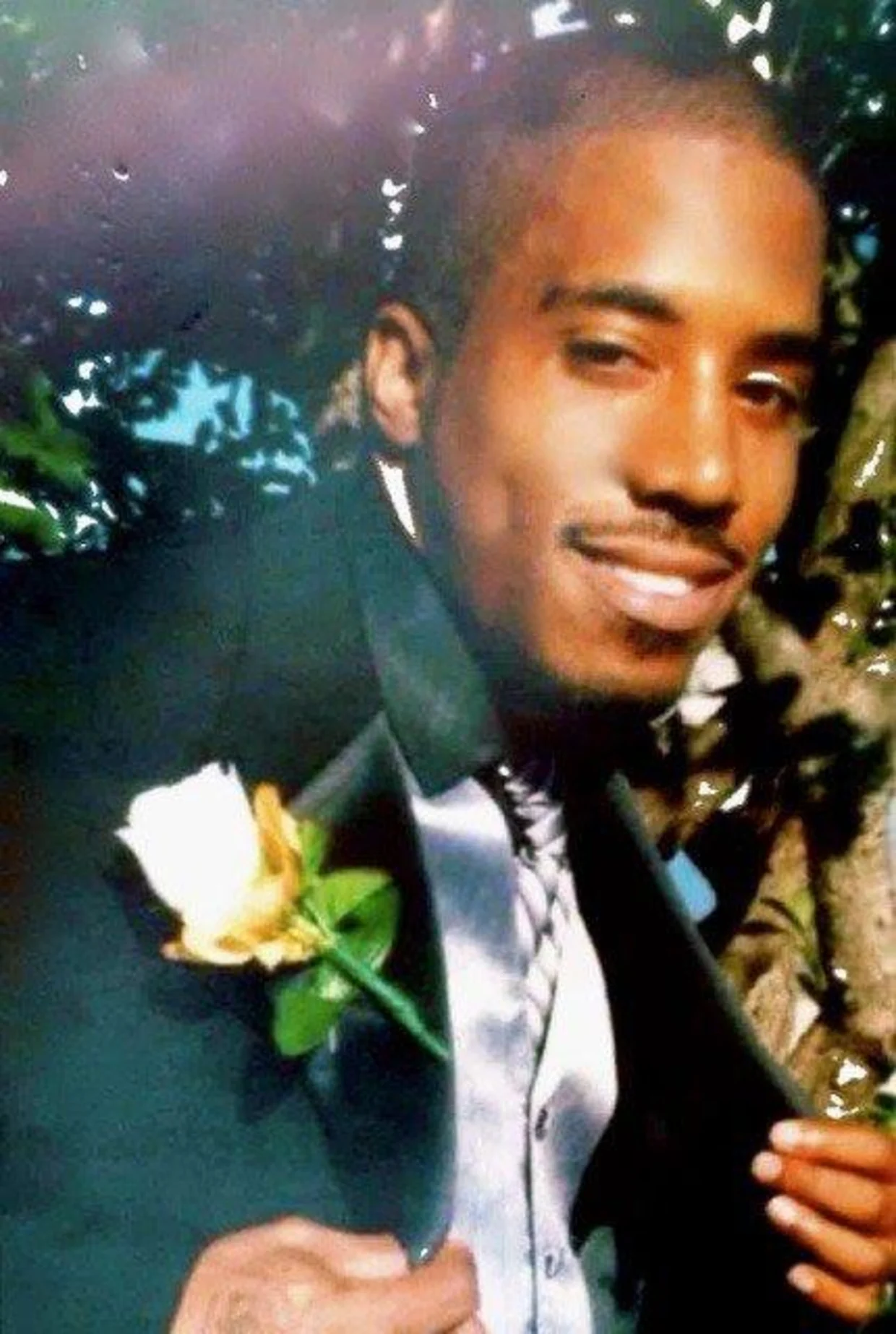

In 2014, 31-year-old Dontre Hamilton was shot 14 times by Milwaukee police officer Christopher Manney. Dontre, who was diagnosed with schizophrenia, was resting in Red Arrow Park outside of a Starbucks in Milwaukee when a barista called the police. After one officer checked on Dontre and left when realizing he was not engaged in any illegal activity, Manney responded to the scene and began frisking Dontre. A confrontation ensued, and Manney killed Dontre.

Police press conferences and media coverage painted Dontre as a dangerous and homeless criminal, even though he had no criminal record and had the receipt for his rent payment in his pocket when he was killed. Manney was eventually fired, and many legal battles regarding his actions and his job followed. No criminal charges were brought against Manney, but in 2017, the Milwaukee Common Council settled a lawsuit with Dontre’s family for $2.3 million.

How should police officers be held accountable in cases like this? What factors should be taken into consideration when determining officer culpability? What level of financial compensation is appropriate for victims and their families?

If you are interested in learning more about this story, watch The Blood Is at the Doorstep, which can be found in the Chapter Resources.

Check Your Knowledge

Licenses and Attributions for Current Events and Trends

Open Content, Original

“Current Events and Trends” by Jessica René Peterson is licensed under CC BY 4.0.

Figure 5.20. “Percentage of Americans by race who believe major changes are needed in policing, 2020” by Jessica René Peterson is licensed under CC BY 4.0. Data from Crabtree, 2020 – Gallup surveys of U.S. adults.

Figure 5.21. “Percentage of officers and public, by race, saying that deaths of Black people in encounters with police are signs of a broader problem, 2016” by Jessica René Peterson is licensed under CC BY 4.0. Data from Pew Research Center Survey of Law Enforcement Officers, 2016.

Figure 5.24. “Non-exhaustive list of high-profile fatalities of Black individuals by police since 2010” by Jessica René Peterson is licensed under CC BY 4.0.

Open Content, Shared Previously

Figure 5.25, left. “Wandbild Portrait George Floyd von Eme Street Art im Mauerpark (Berlin)” photo by Singlespeedfahrer is in the Public Domain, CC0 1.0.

All Rights Reserved Content

Figure 5.19. Table © Council on Criminal Justice (2020) is included under fair use.

Figure 5.22. “Los Angeles’ three-day Shoot, Loot & Scoot 1992 (Rodney King beating)” by ATOMIC Hot Links is included under fair use.

Figure 5.23. “#BLM” by Dana L. Brown is licensed under CC BY-NC-SA,

Figure 5.25, right. Screenshot of Derek Chauvin from video by Darnella Frazier is included under fair use. Modifications: Cropped.

a category of people grouped because they share inherited physical characteristics that are identifiable, such as skin color, hair texture, facial features, and stature

the degree to which society or a community views law enforcement as a legitimate and respected authority

the unfair treatment of marginalized groups, resulting from the implementation of biases, and often reinforced by existing social processes that disadvantage racial minorities

a form of prejudice that refers to a set of negative attitudes, beliefs, and judgments about whole categories of people, and about individual members of those categories because of their perceived race and ethnicity.

a legal doctrine that protects government officials from constitutional rights violation lawsuits over actions taken during their work duties unless those actions violate “clearly established law”

agreement between a court and a police agency or other involved party involving mandates, supervision, and enforcement by the court to make sure that the involved parties are following the plan to improve performance or correct identified wrongs