6.3 Media Representations of Rural

In films, TV shows, and other entertainment media, rural areas have long been depicted as idyllic. The rural idyllic representation includes images of crime-free small towns surrounded by farmland and self-sufficient God-fearing folk. The countryside represents a simple life away from the hustle and bustle of city life (see figure 6.6). Social problems like crime are associated with the city, and any crime that does occur in rural areas is seen as a result of urban encroachment, or the spread of urban people and development to rural areas. There is evidence that rural people tend to hold more traditional and conservative views regarding religion, sexuality, gender roles, politics, and more. However, culture in rural areas is not monolithic. Being thought of as synonymous with whiteness, media depictions of rural America have historically erased the existence and experiences of racially diverse communities and diversity in rural culture.

Recent trends in newspaper closures have greatly impacted rural areas and further diminished the voices of rural people. Some small communities have become what some refer to as news deserts, where access to credible and comprehensive news coverage is non-existent (Center for Innovation and Sustainability in Local Media, 2019). In the absence of local journalism, big metropolitan stations may cover major stories or crimes in rural areas, but the resulting coverage often lacks the local perspective and may consequently make uncommon incidents seem normal. Coupled with the fact that the majority of Americans live in urban spaces and do not experience rural living, this means that the understanding of rural life comes primarily from entertainment media.

Activity: Do You Live in a News Desert?

Use the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill’s tool [Website] to explore news deserts in your state. Do you live in a news desert? How might living in a news desert impact your community? How might it impact outsiders’ view of your community? How important is a local perspective in understanding a community?

Regarding crime and criminal justice in rural areas, entertainment media have traditionally relied on stereotypical depictions of the idyllic. One prime example is The Andy Griffith Show (see figure 6.8), which ran throughout the 1960s. It followed the lives of the wise, laidback Sheriff and his bumbling deputy in rural North Carolina. The fictional town of Mayberry, still quoted to reference small-town America, captured the essence of the sleepy and charming rural town. With few major crime problems to address, local law enforcement was free to engage in comedic shenanigans in each episode that were coupled with traditionally wholesome lessons. The show was massively successful, and according to YouGov (2023), it is the 12th most popular TV show of all time in the United States.

Through a critical lens, the nostalgia felt for this beloved show may be seen as a longing for a rural white South. It was about seven years before the first Black character entered the show, and the racial politics prevalent in the South were largely missing from Mayberry. Some episodes, such as one in which Sheriff Andy Griffith has to explain the Emancipation Proclamation at the breakfast table, emphasize the “whiteness” of the show. Other episodes, such as one in which Deputy Barney Fife speaks in broken English and takes puffs of a peace pipe when playing an “Indian chief” in the local town theater, illustrate the show’s stereotyping of non-white people and culture (Bronstein, 2015; Vaughan, 2004).

The American Western

The American Western genre has a history of romanticizing rural landscapes. Westerns have greatly contributed to the representation of rural America and the understanding of how urbanization impacts rural values. The “bad guys” in this genre are outlaw men, outsiders, and Indigenous people who threaten law-abiding citizens and the rural way of life. In the traditional “cowboys versus indians” trope, white cowboys represent mainstream white values while Indigenous people are dehumanized and depicted as violent savages in need of control (see figure 6.9). The name most synonymous with Westerns is probably John Wayne; the just, moral, stoic, and masculine epitome of the white cowboy (see figure 6.10). Not only do these prejudiced depictions further negative stereotyping of Black, Indigenous, and people of color, but this genre has also whitewashed the American West.

The state of Texas has a worldwide reputation as Cowboy Central for the American West, and shows like Dallas, which follow an affluent white oil tycoon and cattle ranch owner, help put it on the map as such. However:

To be historically accurate, they’d have to say that there’s nothing more North African-Spanish than a Texas cowboy. The tan-galóns, botas, chaparreras, broncos, espuelas, and reatas belonging to today’s cow folk are the legacies of Texas’s first real cowboys: the Mexican vaqueros. And the all-American rodeo? Vaquero through and through (Bullock Texas State History Museum, n.d.).

Cowboys of color have long been absent from the media, or if they are present, they are used as secondary characters. The prevalence of and contributions of ranch laborers, such as the vaqueros, are lost in the popular Western genre (see figure 6.11). In recent decades, some filmmakers have attempted to highlight these deficiencies in the genre, but their success is debatable. For example, the film remake of The Lone Ranger in 2013 was controversial due to the depiction and casting of Johnny Depp as Tonto, the Lone Ranger’s Comanche sidekick. Although this genre has declined in popularity, its stamp on the cultural understanding of the rural American West and its demographics persists.

Objectification and “Horrification” of the Rural

Conversely, the media also depict rural areas as filled with people who are simple, uneducated, and dumb. To the extreme, rural people are characterized as uncivilized, deranged, or “inbred.” Residents of the “backwoods” may be objectified (e.g., Cletus Spuckler from The Simpsons), oversexualized (e.g., Daisy Duke in The Dukes of Hazzard), and dehumanized (e.g., “Appalachian Emergency Room” sketches on Saturday Night Live). See Figure 6.12 and visit the supplemental link if you want to see an example of negative rural stereotyping in pop culture. Some scholars argue that “hillbillies” and “rednecks” have become one of the most openly mocked groups in our society, with no real social repercussions for mocking them. If you want to see an example of rural stereotypes, you can watch the “Appalachian Emergency Room” sketch from Saturday Night Live in the Chapter Resources.

Horror media forms heavily rely on these stereotypes and often juxtapose evil with the pure and peaceful. In remote areas, scary people lurking around can easily evade capture, and police or medical help will not likely arrive in time. Horror films like The Hills Have Eyes, Deliverance, or The Texas Chainsaw Massacre play on audiences’ fears of being alone in an isolated location; the sound of dueling banjos [Streaming Video] is still widely recognizable over 50 years later. Similarly, video games like Resident Evil 7: Biohazard feature diseased and deformed human monsters in rural settings. Such characters are often white and tend to be located in the Southern, Midwestern, or Appalachian regions of the United States.

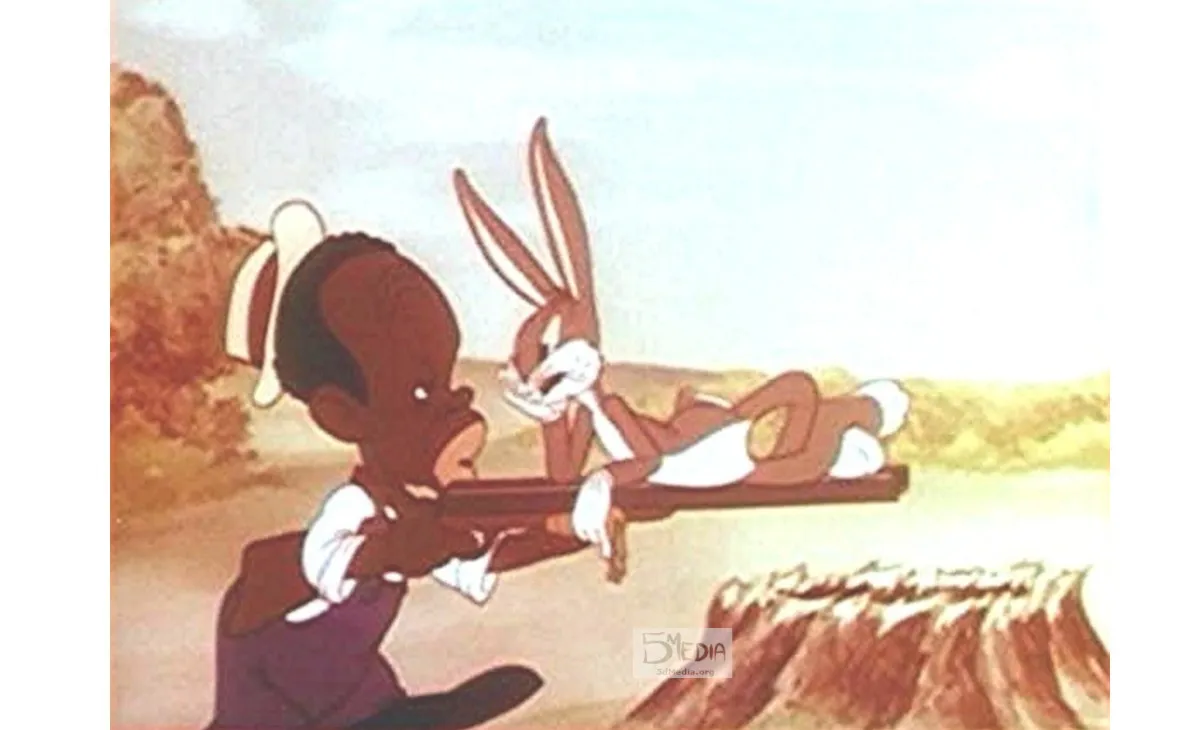

Beyond those discussed in the Western genre, racist stereotypes have long been connected to depictions of people of color in rural areas. For example, the combination of stereotypes related to Black people and the uneducated rural fool led to depictions such as those found in popular Disney films, like Song of the South, and children’s television shows (see figure 6.14). Many of these portrayals stem from minstrel shows, early 19th-century American theater featuring white actors in blackface makeup who stereotyped Black people as entertainment.

The Truth About Rural America and Rural Justice

With all these stereotypes, how do we know what is true? Available research and data show us that crime does occur in rural areas – some types of crime even more so than in urban areas – but it is not deranged hillbillies killing strangers. All the same types of crimes that occur in urban places occur in rural places, just typically at a different frequency. Some rural areas see high rates of domestic violence, drug abuse, and farm crime. In other words, rural places are neither utopias nor hellscapes. Additionally, rural areas are not racially, ethnically, or culturally homogeneous. Diverse populations and their contributions to rural America have long been erased in the media. Consequently, societal expectations and understandings about these settings have been whitewashed.

Inaccurate depictions and understandings of rural America are harmful to the people living there. The assumption that rural communities are crime-free means they are often overlooked or excluded from criminological research. This oversight is exactly how, for example, high rates of domestic violence have gone unaddressed in rural areas for so long. Rural women are at a higher risk of being killed by their current or former male partners compared to their urban counterparts. A study of Appalachian pregnant women found that 81 percent had experienced physical, sexual, or psychological abuse during their current pregnancy. While intersectional feminist criminology has examined the impacts of racism, patriarchy, class oppression, and other discriminatory systems on violence against women in urban areas, much less work has been done in rural and remote areas (DeKeseredy, 2021).

Furthermore, if rural residents are portrayed and viewed as dumb, uneducated, or depraved, it is easy to ignore them in mainstream political discussions. Crime in these communities can easily be written off as a result of backwoods thrill-seeking (e.g., illustrated by shows like Buckwild, the “Jersey Shore of rural West Virginia”) or the behavior of urban undesirables (e.g., outsiders and people of color from urban areas). Why would we need to address the rehabilitation of offenders who are just inbred monsters? Or access to justice for victims who choose to live in these scary, uncivilized places? Should the fact that gun availability and ownership rates in rural America – especially among white men (Pew Research Center, 2017) – exceed that of urban settings be a part of our public debate on gun control, or are firearms simply an urban Black problem, as the news might lead you to believe?

The following sections will further shine a light on the realities of race, crime, and justice issues in rural America. Namely, we will explore the topics of rural Black America, migration and immigration to rural America, and Indigenous populations in rural America. Finally, we will briefly address issues of racial and ethnic justice in rural spaces across the globe.

Check Your Knowledge

Licenses and Attributions for Media Representations of Rural

Open Content, Original

“Media Representations of Rural” by Jessica René Peterson is licensed under CC BY 4.0.

Open Content, Shared Previously

Figure 6.6. Images in collage clockwise from top left: Image of tractor by Jakob Rosen; Image of cows by Annie Spratt; Image of hunters by Evgeniy Smersh; Image of barn by Tanner Boriack; Image of cowboys by Bailey Alexander; Image of pigs by Diego San; Image of man in field by Priscilla Du Preez; Image of house with sun rising by John Fornander; Image of man in overalls by Steven Weeks.

Figure 6.7. Photo by Parsing Eye is licensed under the Unsplash License.

All Rights Reserved

Figure 6.8. Image from The Andy Griffith Show is included under fair use.

Figure 6.9. Image from Tintin in America is included under fair use.

Figure 6.10. Image from Starlog Press Publications is included under fair use.

Figure 6.11. Roping, Ninety-Six Ranch by Carl Fleischhauer is included under fair use. Courtesy of Paradise Valley Folklife Project collection, 1978–1982 (AFC 1991/021), American Folklife Center, Library of Congress.

Figure 6.12, left. Image of Catherine Bach as the character Daisy Duke from The Dukes of Hazzard is included under fair use.

Figure 6.12, right. Image of Cletus Spuckler from The Simpsons is included under fair use.

Figure 6.13, left. Image from The Texas Chainsaw Massacre is included under fair use.

Figure 6.13, right. Image from Resident Evil 7: Biohazard is included under fair use.

Figure 6.14. Image from All This and Rabbit Stew is included under fair use.

simply put, non-urban spaces with lower populations and lots of undeveloped land

the depiction of rural spaces as simple, wholesome, peaceful, and without crime

the spread of urban people and development to rural areas (may also be referred to as urban sprawl)

a group’s shared practices, values, and beliefs.

communities where access to credible and comprehensive news coverage is non-existent

movement of people from rural settings to cities and metropolitan areas that results in the growth of urban places

a group of people living in a defined geographic area that has a common culture

widely held beliefs or assumptions about a group of people based on perceived characteristics.

early 19th-century American theater featuring white actors in blackface makeup who stereotyped Black people as entertainment

a form of prejudice that refers to a set of negative attitudes, beliefs, and judgments about whole categories of people, and about individual members of those categories because of their perceived race and ethnicity.

a category of people grouped because they share inherited physical characteristics that are identifiable, such as skin color, hair texture, facial features, and stature