6.4 Rural Black America

Media depictions of rural and urban communities might lead you to believe that Black communities are primarily found in inner cities. News and entertainment sources make this seem particularly true when we look at illicit substance use. Not only do stereotypes regarding drug use incorrectly point to the Black population as the predominant users, but these stereotypes also place Black people who use substances in a graffiti-laden metropolitan area. These stereotypes are wrong for three reasons.

First, research such as the National Survey on Drug Use and Health shows that drug use between Black and white populations in the United States does not drastically differ. In 2021, for example, Black and white Americans were equally likely to have misused opioids or have a substance use disorder (SAMHSA, 2021). Second, drug use is just as prevalent an issue in rural America as in urban America. The Centers for Disease Control announced that the rate of deaths as a result of drug overdose in rural America exceeded that of urban America in 2018, with 2020 rates being only slightly higher in urban counties (Spencer et al., 2022). Children in rural schools have reported similar rates of substance use to their urban counterparts, with certain substances being used more in rural communities (Lenardson et al., 2020). Third, the dichotomies of rural versus urban and white versus Black are inaccurate. In other words, drug use is not a Black or urban problem, and rural does not equal white.

Similar to the racial disparities in arrest, conviction, and incarceration rates discussed throughout this book, Black people are disproportionately incarcerated in rural prisons as well. This includes both Black people who live in urban areas but are incarcerated in a rural facility, as well as those who lived in a rural area before being sent to prison. For example, in the Northeastern region of the United States, nearly 40 percent of the rural Black population is incarcerated (Center on Rural Innovation, 2023a).

The “Black Belt” and Appalachia

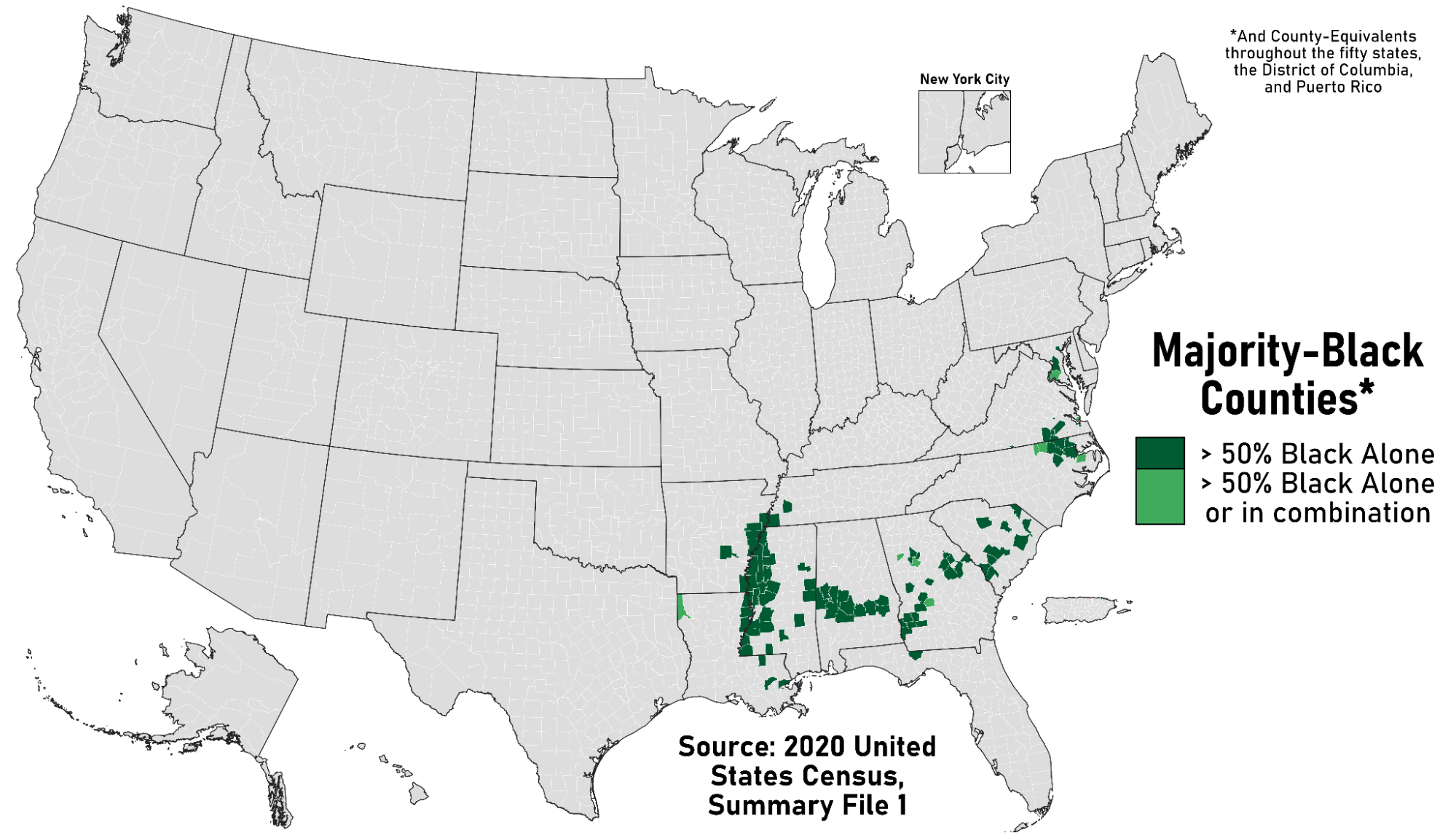

Contrary to popular notions, rural America consists of Black communities, many of which can be found in the Southern and Appalachian regions of the United States. The “Black Belt” is an area in the South that consists of predominantly Black communities (see figure 6.15). The term originally referred to the fertile black soil in the area that made it ideal for growing cotton and other crops. The rich soil attracted plantations that forced labor from enslaved Black people. Over time and due to the history of slavery and other racist policies, these locations became majority-Black communities,, and the term took on a different meaning. While Black people only make up about 8 percent of the total rural population in the United States, nearly 9 out of 10 rural and small-town Black people live in the Southern region, many of whom are concentrated in states such as Alabama, Georgia, Mississippi, Arkansas, Louisiana, Virginia, and the Carolinas (Housing Assistance Council, 2012; U.S. Department of Agriculture, 2020).

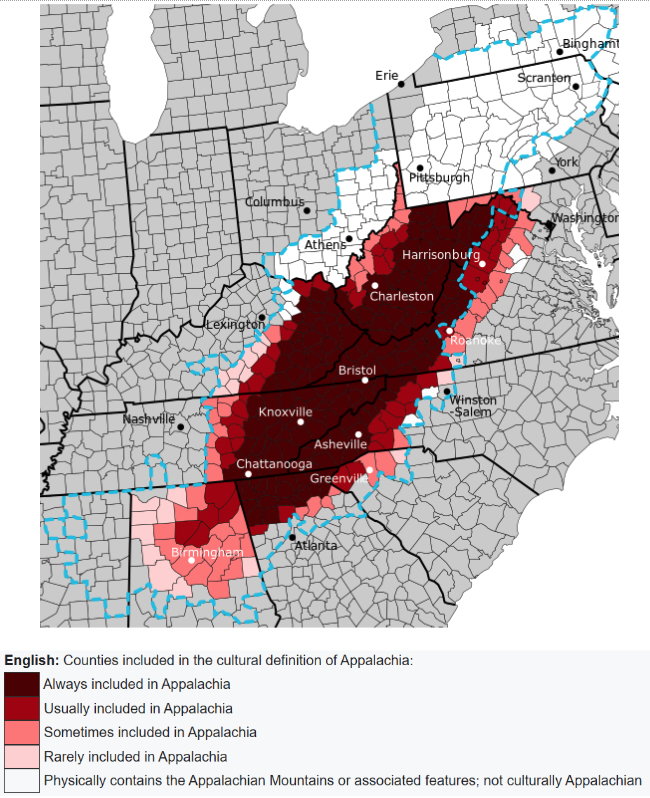

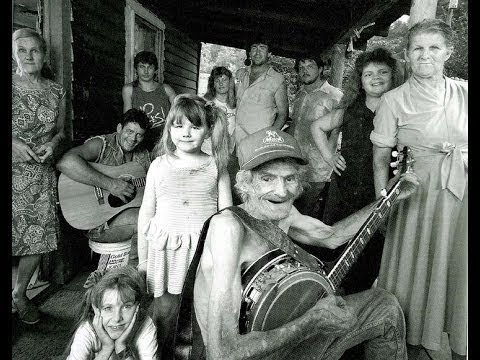

Appalachia, the areas in the Appalachian Mountains in the Eastern region of the United States, see figure 6.16, has many negative stereotypes associated with it, some of which were discussed previously in the section on the objectification and horrification of the rural. Most of these have targeted the history of immigrant coal workers and portray Appalachian people as poor white “hillbillies” (see figure 6.17). Although the exact perimeters of Appalachia are debatable, West Virginia has and continues to be a core representative of Appalachia.

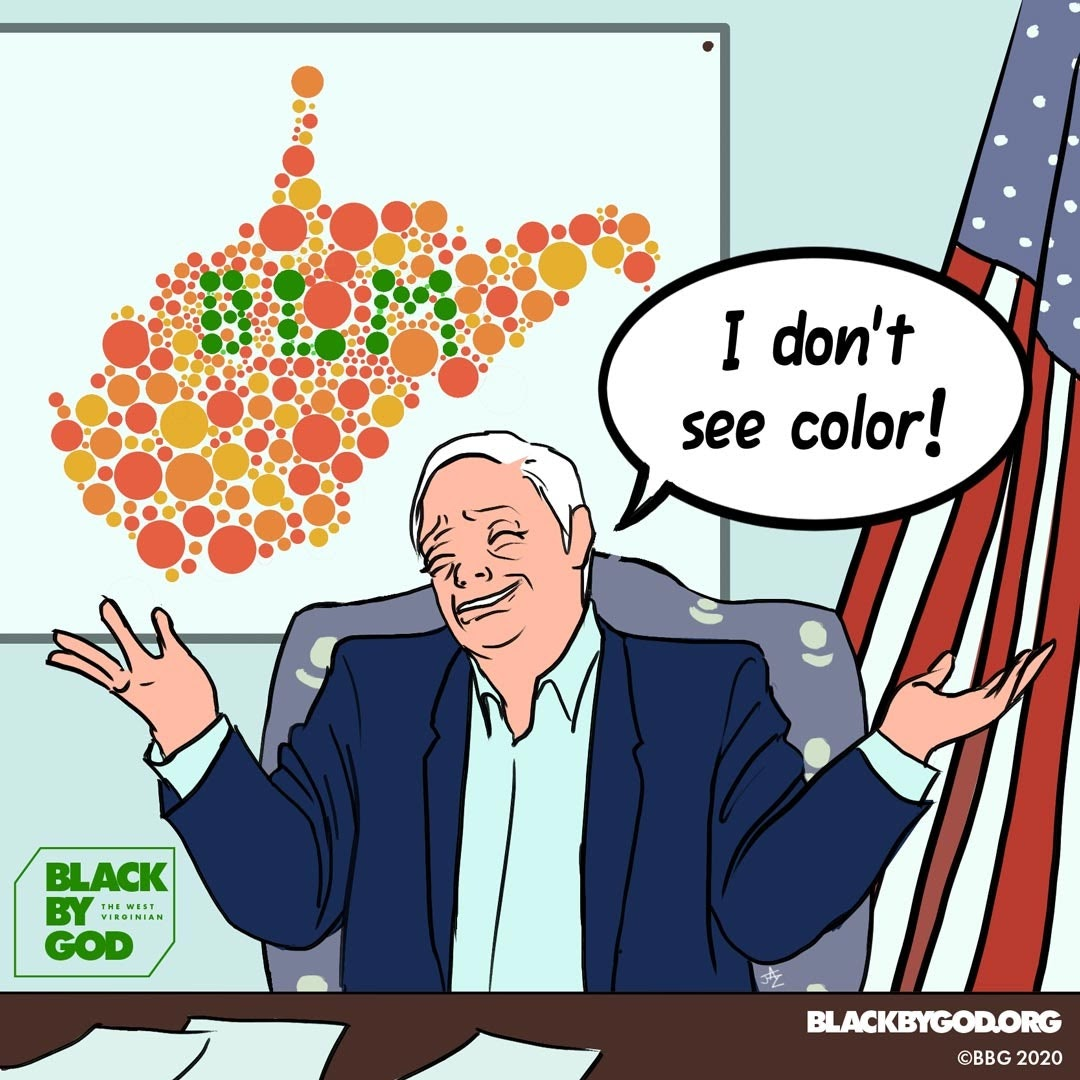

Although Black people only account for about 8 percent of Appalachia (Appalachian Regional Commission, n.d.), the Black community throughout the region has a rich history. The banjo that is typically associated with white rural folks, especially in Appalachia, was introduced by Black blues musicians. Some Black residents have expressed attachment to and a reclaiming of the “hillbilly” identity that often excludes people of color. Researchers, activists, and organizations that bring the experiences of Black Appalachians forward are growing in activity and prominence. For example, the non-profit organizations Black in Appalachia and the Black Appalachian Coalition (BLAC) center Black voices and lived experiences to promote research, education, decolonization, and policy improvement in Appalachia.

Organizations such as BLAC have been paramount in bringing attention to environmental racism faced by Black communities in Appalachia and elsewhere in the United States. Environmental racism is a policy or practice that, intentionally or unintentionally, differentially affects or disadvantages people based on race or color (Bullard, 1993). People of color in rural areas are particularly vulnerable to environmental racism. A prime example can be seen in Dickson, Tennessee. In 1988, government officials became aware of high concentrations of carcinogens that a manufacturing company had dumped into a landfill. The landfill was located in the historically Black enclave outside of the predominantly white city of Dickson. The toxic chemicals leaked into the water supply, and even though some white residents were provided with alternative water sources, Black residents were told it was safe to consume the water. Years later, members of the Holt family suffered serious health problems, including cancer, that led to death from drinking the contaminated well water on their farm (Natural Resources Defense Council, 2022).

Many examples of environmental crimes against communities of color can be found, but BLAC is currently fighting for social and environmental justice for the small town of Clairton, Pennsylvania. Nearly 40 percent of the town’s residents are Black and concentrated near the U.S. Steel Clairton Coke Works plant. As the nation’s largest manufacturer, Coke Works produces nearly 5 million tons of coke – the material used to make steel – annually. This process produces harmful chemicals that pollute the air, and Black residents are disproportionately affected by the pollution and related illnesses (BLAC, n.d.; EPA, 2023). If you are interested in learning more, see the documentary Hillbilly (2018) in the Chapter Resources.

Activity: Black by God

Black by God , a community-led news organization founded by Crystal Goode in West Virginia, champions the voices of Black residents in Appalachia. Explore the website and Instagram account [Website] for Black by God. How might a community-led news organization such as this help dispel myths and stereotypes about rural people in Appalachia? How might this organization impact social and criminal justice policies?

Racism in Rural Communities

Overall, people of color in rural America, including Black, Hispanic or Latinx, Asian, and Native American people, are 21 times more likely to live in a predominantly white county compared to people in metro areas (Center on Rural Innovation, 2023b). Individual and systemic racism may be particularly strong in areas that have historic ties to slavery or hate groups such as the Ku Klux Klan (KKK). People of color, especially the Black population, in predominantly white rural communities express feelings of being “guests” rather than actual community members and being ignored or overlooked (Walton, 2019). In some cases, such treatment may evolve into various forms of victimization and hate crimes.

Hate crimes are property or violent crimes that are motivated by bias, usually related to one’s actual or perceived identity regarding race, ethnicity, color, country of origin, religion, gender or gender identity, sexuality, or disability. In the 1990s, a Black disabled man named James Byrd Jr. was murdered in the rural town of Jasper, Texas (see figure 6.19). Three men drove James to a secluded area, beat and tortured him, tied him to the back of their truck with a chain, and dragged him nearly three miles through the town until he died. They left James’s body in front of a Black church. This horrific murder was motivated by anti-Black racism, and at least two of the responsible men were known white supremacists. This case is a prime example of an anti-Black hate crime in rural America, and it is one of two cases that sparked the passage of the Matthew Shepard and James Byrd Jr. Hate Crimes Act in 2009.

Rural areas provide geographic isolation, limited police presence, and, in many cases, sympathetic political and social ideologies that hide or protect bias-motivated victimization. Hate groups and extremist militias (see figure 6.20) have increasingly become a concern in the 21st century, and some groups take advantage of the rural environment for privacy or firearms training. With the majority of recognized hate groups espousing white supremacist ideology (Gerstenfeld, 2012), they pose a particular threat to people of color in rural communities. While some groups maintain secrecy, others loudly proclaim their beliefs. For example, the “white-only” group known as Asatru Folk Assembly announced on its Twitter in 2022 that they had purchased land in rural Tennessee intended to house their headquarters, a temple, and a school for young people (Gais et al., 2023). Groups like this, with goals of indoctrinating children into hateful racist ideology, pose a significant threat to people of color living in these areas.

Check Your Knowledge

Licenses and Attributions for Rural Black America

Open Content, Original

“Rural Black America” by Jessica René Peterson is licensed under CC BY 4.0.

Open Content, Shared Previously

Figure 6.15. “2020 Census – Majority-Black Counties in the United States” by Abbasi786786 is licensed under CC BY-SA 4.0.

Figure 6.16. “Датотека: Counties included in Appalachia map” by Leviavery is in the Public Domain, CC0 1.0.

All Rights Reserved Content

Figure 6.17. “George’s Branch Porch” by Shelby Lee Adames is included under fair use.

Figure 6.18. “I Don’t See Color” by Black by God is included under fair use.

Figure 6.19. Image of James Byrd Jr. is included under fair use.

Figure 6.20. Image by Max Blau is included under fair use.

simply put, non-urban spaces with lower populations and lots of undeveloped land

widely held beliefs or assumptions about a group of people based on perceived characteristics.

Once a term referring to rich black soil, it now refers to area in the Southern region of the U.S. that consists of predominantly Black communities, primarily as a result of the history of slavery

a form of prejudice that refers to a set of negative attitudes, beliefs, and judgments about whole categories of people, and about individual members of those categories because of their perceived race and ethnicity.

a policy or practice that, intentionally or unintentionally, differentially affects or disadvantages people based on race or color (Bullard, 1993)

a category of people grouped because they share inherited physical characteristics that are identifiable, such as skin color, hair texture, facial features, and stature

refers to how racism is embedded in the fabric of society and how institutional processes are used to maintain systematic discrimination through the complex interactions of large scale societal systems, practices, ideologies, and programs that produce and perpetuate inequities for racial minorities. Also referred to as institutional or structural racism.

property or violent crimes that are motivated by bias, usually related to one’s actual or perceived identity regarding race, ethnicity, color, country of origin, religion, gender or gender identity, sexuality, or disability

shared social, cultural, and historical experiences of people from common national or regional backgrounds that make subgroups of a population different