8.3 History of the Juvenile Justice System

The full history of the invention and growth of the juvenile justice system deserves far more than can be covered in this one chapter and, especially, in this one section. For that reason, we will focus on some key developments and their long-term impact, particularly for youth of color.

The early American juvenile justice system was designed to provide housing and proper education to poor white children whose parents were allegedly not doing a good enough job. These children were placed in a house of refuge like the one shown in Figure 8.4. The government gave itself the authority to take white children away from their families to mold them and give them the morals and values that the founders wanted.

Children of color were initially left out of this system because they were not seen as children. Black children of enslaved people were seen as property and valuable as laborers. Even after the Thirteenth Amendment abolished slavery (except as punishment for a crime), Black children could be forced into apprenticeships with their former slaveholders. Because Southern plantation owners relied on the free labor of enslaved people, abolishing slavery was unpopular. For this reason, “Black Codes” were created in most areas that controlled the movement and access of people of color, going so far as to make illegal behaviors that would not be so if the person were white. Once incarcerated for the Black Code or other crimes, Black people, including children, could be returned to plantation work through convict leasing (Bell, 2015).

To try to understand or justify these practices, researchers then began to try to predict criminality based on race. The methods and conclusions of these studies claimed that many youth of color were “feeble-minded” and could not be trusted to remain in society without causing harm. This justified their detainment and even sterilization, especially for Mexican and Black youth (Bell, 2015). At the Fred C. Nelles Youth Correctional Facility in California, for example, superintendent Lewis Terman argued in 1916 that the “Spanish-Indian and Mexican” youth in his facility were “feeble-minded” and needed to be sterilized to protect public safety (Bell, 2015; Chávez-Garciá, 2012).

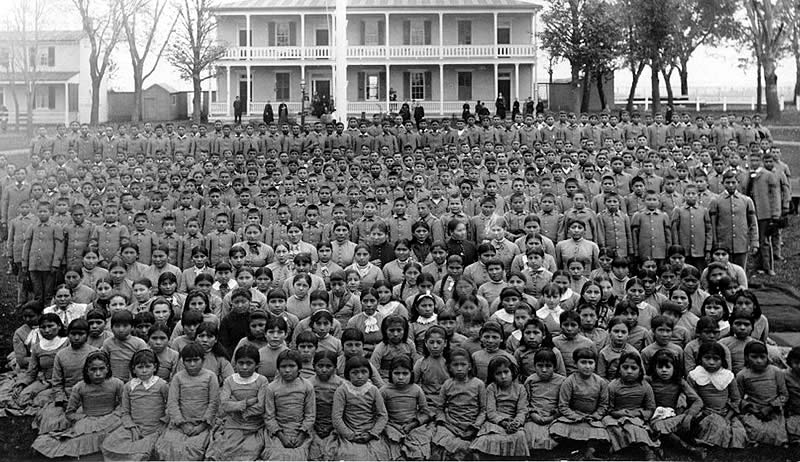

The practice of detaining Black and Mexican youth also extended to Indigenous children. The U.S. government created more than 350 Indian boarding schools, like the Carlisle Native Industrial School, shown in figure 8.5 (The National Native American Boarding School Healing Coalition, n.d.). In these schools, thousands of Indigenous children were removed by government agents from their families and indoctrinated with white cultural values and language. The goal was to make them forget their language and traditions so they could be turned into “good” white children. One of the first of these boarding schools, called the Indian Industrial and Training School, was established in 1880 in Forest Grove, Oregon, on the campus of Pacific University, which had donated the land and lobbied on behalf of the school (Hotch and Guggemos, n.d.).

Poor white children were placed in houses of refuge. Black children were re-enslaved in forced apprenticeships. Black and Latinx youth were institutionalized as “feeble-minded,” and Indigenous youth were forced into boarding schools for white indoctrination. Every one of these moves was full of trauma and limitless abuse.

The current juvenile justice system sits on this history. It is a system developed on racist principles, and it continues to enforce racist practices and policies that are difficult to overturn. Working toward a more equitable future is a slow process, taking decades to see even the smallest gains. The result of this history is a system where youth of color are disproportionately represented. To view a summary of the history of the juvenile justice system, watch the video in the Chapter Resources.

Becoming a Juvenile Delinquent

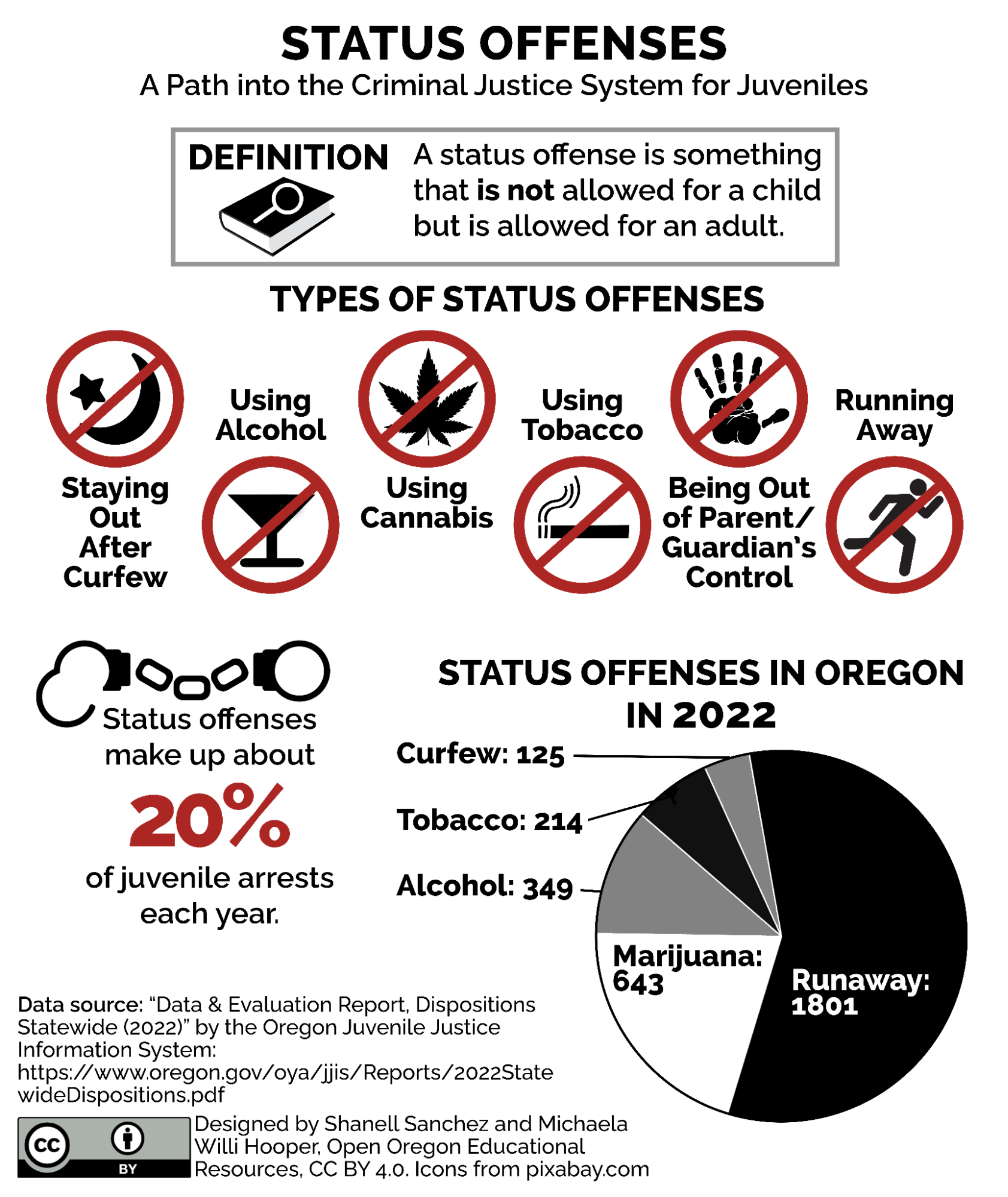

Initially, a child was considered a juvenile delinquent if they were poor or non-white. Today, these are not the determining factors, although they are often still part of the description of kids caught up in the system. In a broad general sense, “juveniles” are typically considered those under the age of 18. However, the age of criminal responsibility varies by state. For the majority of states, anything done against the law by someone who is 18 or older is considered a crime. For those under the age of 18, there is a different set of rules. If you want to learn more, see the Office of Juvenile Justice and Delinquency Prevention’s “Age Boundaries of the Juvenile Justice System” in the Chapter Resources. While under the age of 18, one is not considered “criminal,” but rather “delinquent” for any behavior outside of what is determined acceptable for a minor. Crimes are illegal for anyone, whereas some delinquent acts are illegal only for juveniles. These special rules for youth behavior are status offenses or something that is not allowed for a child but is for an adult, as explained in Figure 8.6. If you want to learn more, see the video in the Chapter Resources where Annie Salsich from the Coalition for Juvenile Justice argues that status offenses should not be addressed within the criminal justice system.

For example, missing school (truancy), running away from home, being out past curfew, drinking alcohol, smoking cigarettes, or even simply “acting out” are all status offenses that are prohibited by the law for anyone under the age of 18. Acting out is an especially vague rule that gives a lot of discretion to those in positions of authority and generally means “beyond the control of the parent(s) or guardian(s)” (JJGPS, n.d.). Acting out can include anything deemed inappropriate or unacceptable by the person reporting the offense, including school personnel, law enforcement, social workers, probation officers, or parents or guardians. In addition, there are no clearly defined parameters for what is appropriate and acceptable behavior.

The vagueness of “acting out” causes many youth to be swept up into the system without ever having committed a crime. Instead, they are considered “at risk” of committing a future offense. Kids can be detained until they turn 18 under the assumption that they are likely to get in trouble if not held in a secure facility. This is unique to youth. Adults are protected by law from being incarcerated based on a belief that they may someday commit a crime.

Imagine how this level of discretion and these special rules for youth are applied in different communities. Behavior that in some neighborhoods would be met with interventions from caring adults and discipline within the home, in a neighborhood that is overpoliced, is likely to be met with handcuffs. Studies show that youth of color are not committing more status offenses than their white peers. Rather, youth of color are simply more likely to be caught, detained, and punished than their white peers (VanderPyl, 2018). It is also frighteningly common for a white female teacher to be uncomfortable with the behavior, speech, or actions of a young Black male student and misinterpret his behavior as dangerous or threatening (Fisher et al., 2022; VanderPyl, 2018). She can claim he is “acting out” and get him caught up in the juvenile justice system with her implicit racism (Fisher et al., 2022).

Check Your Knowledge

Licenses and Attributions for History of the Juvenile Justice System

Open Content, Original

“History of the Juvenile Justice System” by Taryn VanderPyl, revised by Jessica René Peterson, is licensed under CC BY 4.0.

Figure 8.6. “Status Offenses: A Path into the Criminal Justice System for Juveniles” by Shanell Sanchez and Michaela Willi Hooper, Open Oregon Educational Resources, is licensed under CC BY 4.0.

Open Content, Shared Previously

Figure 8.4. “House of Refuge for Poor White Children” by Local History & Archives, Hamilton Public Library, is in the Public Domain.

Figure 8.5. “Pupils at the Carlisle Native Industrial School in Pennsylvania (c. 1900)” is in the Public Domain.

a category of people grouped because they share inherited physical characteristics that are identifiable, such as skin color, hair texture, facial features, and stature

a group of people living in a defined geographic area that has a common culture

age at which an individual becomes legally responsible for criminal law violation through the adult court system

a form of prejudice that refers to a set of negative attitudes, beliefs, and judgments about whole categories of people, and about individual members of those categories because of their perceived race and ethnicity.