8.4 Before Juvenile Justice System Contact

Historically, the American juvenile justice system was designed with differing goals for youth. Depending on the youth’s race, the system was designed to protect the child, fix the child, or protect society from the child. But in the mid-1990s, the system shifted to a fear-based model that prioritized a negative approach to dealing with what society came to see as dangerous, troubled teenagers.

Two new forms of entertainment became popular in the 1980s and 1990s: rap and video games. In the late 1980s, rap music became a bestselling music genre throughout the United States. Although it started in the 1970s, it didn’t reach mainstream America for a while. Once music executives learned about the new genre of music, they jumped all over it and took it from “street art” among African-American teens to Main Street, U.S.A. Run-D.M.C., N.W.A., Ice-T, the Notorious B.I.G., and Tupac Shakur paved the way for white groups like the Beastie Boys and female groups like Salt-N-Pepa. The music became known as “gangsta rap” and glamorized violence and crime as a major component of the newly popular gangster image. As the genre grew in popularity throughout the 1990s, artists like Snoop Dogg, Dr. Dre, Wu-Tang Clan, and Nas became known in middle America, bringing rap battles and messages from the coasts all across the country.

In 1985, Tipper Gore (wife of then-Senator Al Gore) heard the song “Darling Nikki” by Prince and was scandalized. She and other concerned parents formed the Parents Music Resource Center (PMRC), which also became known as the “Washington Wives” because of the four founding women who were all married to senators and others in positions of political power. These women joined together under the notion that they needed to save the morality of America’s youth. On September 19, 1985, the Senate held a hearing with representatives from the PMRC, three musicians (Dee Snider of Twisted Sister, Frank Zappa, and John Denver), as well as senators and other “experts.”

As a result of the work of the PMRC and the Senate hearing, a newly required parental advisory label (seen in Figure 8.7) was put on all albums with explicit content. The first album sold with the label was “Banned in the U.S.A.” by 2 Live Crew in 1990. Interestingly, although artists and the music industry fought the label, worrying it would hurt sales, by the late 1990s, it ended up making albums with the label more popular, and sales rose as a result (Bowes, 2022). Some record companies even started using it as a marketing tool for teens wanting to rebel against their parents.

Controversy over violent video games also began during this time. In 1993, there was a joint Senate Judiciary and Government Affairs Committee hearing focused on violence in video games. This was in response to Mortal Kombat, which was among the first few games to feature realistic and lifelike violence.

In 1995, further fueling the moral panic, criminologist and political scientist John Dilulio published faulty research claiming that, based on the data, the United States was about to be overrun by cruel, violent, heartless teenagers who were mostly inner-city racial minorities out to kill white adults. He called this generation of terrifying kids “superpredators.” The mainstream media gave Dilulio’s unscientific ideas publicity and airtime. Despite his research being debunked, the impact of this horrible prediction was a new, harsh, and lengthy sentencing for juveniles that continues today. Oregon’s Measure 11, which will be discussed more later in this chapter, is an example of mandatory minimum sentencing extended to youth as young as 15 years old that came about during the superpredator era. Many states enacted similar “tough on crime” legislation around this time. The superpredator myth fed into the other fears already circulating in society and influenced how adults in power treated kids in the juvenile justice system.

The culmination of the image of terrifying teenagers in the 1990s was the Columbine school shooting in 1999. Although it was not the first school shooting, it was the one that grabbed hold of the American consciousness and flamed existing fears. It was the deadliest school shooting for many years and terrified the general public.

Media messages fed into this fear and promoted the notion of superpredators fueled by explicit music and violent video games. Then-President Bill Clinton argued in his speech before signing the Violent Crime Control and Law Enforcement Act of 1994:

Now, too many kids don’t have parents who care. Gangs and drugs have taken over our streets and undermined our schools. Every day, we read about somebody else who has gotten away with murder. But the American people haven’t forgotten the difference between right and wrong. The system has. The American people haven’t stopped wanting to raise their children in lives of safety and dignity, but they’ve got a lot of obstacles in their way (Clinton, 1994, p. 1540).

The only possible response, according to those in positions of authority, was to crack down on this generation of “bad” kids with severe punishments in the juvenile and criminal justice systems. The fear that ran rampant through the 1990s caused reactionary and fear-based policies that have led to more harm than good for youth, particularly those of color. That fallout has continued for decades and is only coming to the surface for some now who are recognizing that what was done was not only not helpful, but incredibly harmful. If you want to learn more about the “superpredator scare,” you can view the video in the Chapter Resources.

School-to-Prison Pipeline

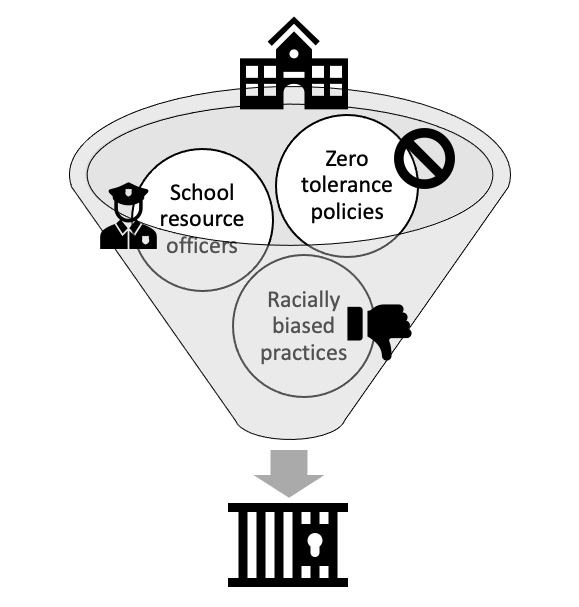

After the Columbine school shooting, schools responded by bringing law enforcement into schools to keep students safer. School resource officers and zero-tolerance discipline policies became commonplace in schools nationwide. This is a good example of when good intentions have very different impacts and negative unintended consequences. Although the notion was to keep students safer, schools ended up turning most of their behavior management and discipline, which in the past had been handled by teachers, principals, and parents, over to law enforcement. This unintentionally criminalized what was previously just normal adolescent behaviors. More kids were being suspended, expelled, and even arrested for insignificant actions.

The trend of exclusionary discipline practices (those that remove kids from school, like suspension and expulsion) led to what has become known as the school-to-prison pipeline. Through harsh discipline practices, students are pushed out of schools, into the streets, and into the juvenile justice system. The youth most dramatically impacted by these new practices are Black and Latinx boys. Specifically, zero-tolerance discipline policies (those that leave no room for discretion or considering the circumstances around what may have occurred) have been particularly disastrous for Black students. Over 70 percent of students involved in school-related arrests or referrals to law enforcement are Black or Latinx, and 95 percent of school suspensions are for minor infractions (CRDC, 2021). Black students are more than three times as likely as their white peers to be suspended (even for the same infraction), and 40 percent of students expelled each year are Black (CRDC, 2021).

These negative and punitive experiences increase the likelihood of a student dropping out of school permanently and becoming involved with the juvenile justice system. As reported by the American Bar Association and JusticePolicy.org (2018):

- “Students who have been suspended or expelled are two times more likely to drop out than students who have not.”

- “Black students are suspended or expelled three times more frequently than white students.”

- “Of students disciplined in middle or high school, 23 percent are involved in the juvenile justice system.”

Perhaps then not surprisingly, 68 percent of all men in prison do not have a high school diploma, and 61 percent of them are Black or Latinx, despite being only 30 percent of the U.S. population (CRDC, 2021).

Risk Factors for Delinquency

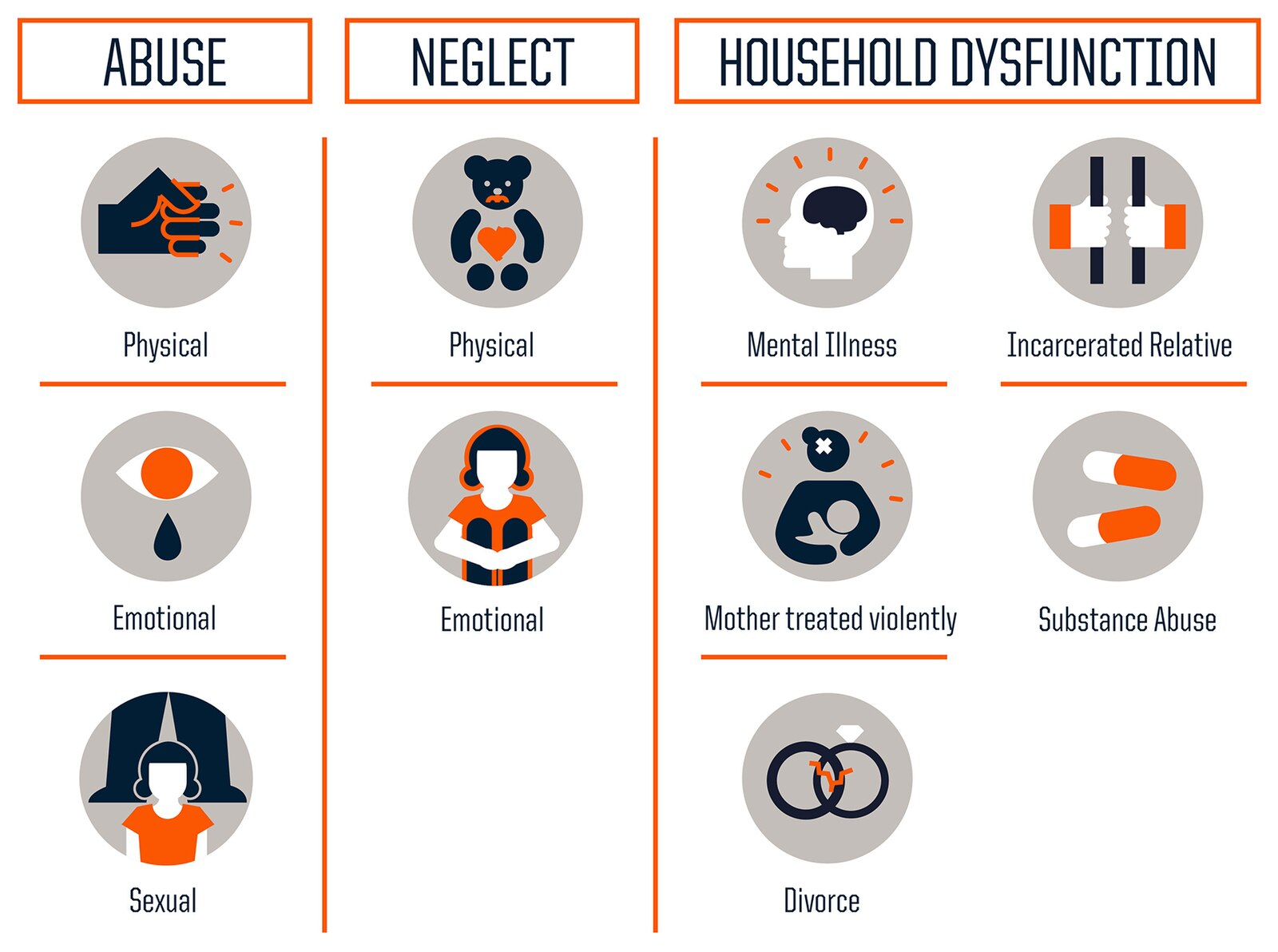

Negative school experiences and exclusionary discipline are risk factors for delinquent behavior and juvenile justice system involvement. So, too, are many harmful and traumatic experiences for youth known as adverse childhood experiences (ACEs). The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) has identified specific traumatic events that may occur in a child’s life at any time before they reach the age of 18 that have long-term damaging effects (CDC, 2023). Figure 8.10 shows the 10 most common traumatic experiences considered ACEs, including experiencing violence, abuse, or neglect; witnessing violence; the death of a family member; witnessing substance use problems in the home; mental health problems at home; parental incarceration; and more. Studies show ACEs are directly linked with juvenile justice system risk and involvement. For example, in one survey of over 64,000 youth who had justice system involvement in Florida, 97 percent of these youth had at least one ACE, and 50 percent had four or more of the 10 ACEs (Baglivio et al., 2014).

Knowing about the prevalence of ACEs and their link to delinquent and criminal behaviors, we have the opportunity to recognize, prevent, and intervene in these experiences for youth. The higher the number of ACEs someone experiences, the greater their risk of a long list of negative outcomes, including justice system involvement. The more traumatic experiences someone has, the greater their risk becomes. Trauma is compounding, which means it gets worse as more trauma is experienced. There is cause for hope, though. We now know that trauma can be transformed. We now know that juveniles who respond in antisocial ways are likely doing so because of what they have been through. This new perspective is the basis of trauma-informed care. This framework trains those working in behavioral health services to ask, “What has happened to you?” rather than, “What is wrong with you?” (SAMHSA, 2014). Although trauma-informed care could work as a preventative and protective measure for youth harmed by the school system and elsewhere, it is more often only implemented after the young person has been acting out as a result of the harm they have experienced, causing additional harm to others. Using trauma-informed care earlier can change our response to trauma and could even change the direction of the school-to-prison pipeline.

Check Your Knowledge

Licenses and Attributions for Before Juvenile Justice System Contact

Open Content, Original

“Before Juvenile Justice System Contact” by Taryn VanderPyl, revised by Jessica René Peterson, is licensed under CC BY 4.0.

Figure 8.9. “Graphic of the school-to-prison pipeline process” by Taryn VanderPyl is licensed under CC BY 4.0.

Open Content, Shared Previously

Figure 8.7. Parental Advisory Label for Explicit Lyrics in Songs (1990–2001) is in the Public Domain.

Figure 8.8. “Miami Dade Schools police car” by Phillip Pessar is licensed under CC BY 2.0.

Figure 8.10. “List of generalizable ACEs common in children, according to the CDC” is in the Public Domain.

a category of people grouped because they share inherited physical characteristics that are identifiable, such as skin color, hair texture, facial features, and stature

a group of people living in a defined geographic area that has a common culture