8.5 During Juvenile Justice System Involvement

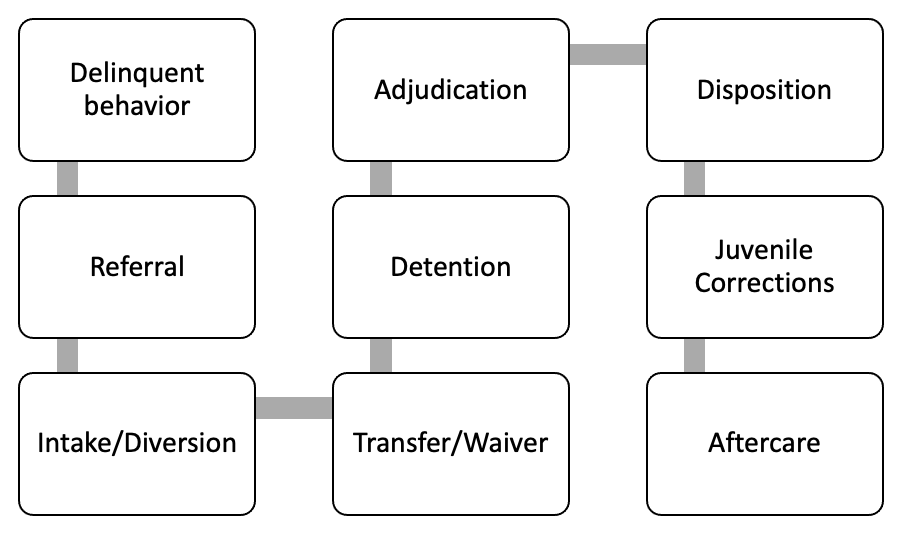

In this section, we’ll examine the juvenile justice system and how it treats youths differently based on their race. Racial minority youth are overrepresented and receive disproportionately punitive treatment at every single step of the juvenile justice system. Once they have been referred to the courts from the school, home, or social workers (again at much higher rates than their white peers for the same behaviors), the biased treatment continues. First, let’s identify the steps of the juvenile justice system as shown in Figure 8.11. The language is different from the adult system, but the general steps are pretty much the same (AECF, 2020). The difference is that the adult system is focused on punishment, whereas the juvenile system is focused on rehabilitation.

Delinquent behavior can range from typical adolescent or teenage rebellion of testing limits (which is a natural stage of development), up to more serious crimes. Although all youth participate to some degree in these behaviors, the consequences can be dramatically different depending on the race of the youth. Discretion is a significant component of referrals for juveniles, so implicit biases end up playing a very large role in which behaviors are dismissed (such as a teacher handling disruptive behavior themselves without involving police or kids throwing a party in a neighborhood where the police are more apt to simply break it up instead of arresting anyone). Students of color are more likely to live in neighborhoods and attend schools with a higher police presence and, therefore, are more likely to have contact with the juvenile justice system for the same behaviors as their white peers (AECF, 2020).

Youth enter the system through either arrests or referrals. Law enforcement makes arrests, but referrals (as previously discussed) can be made by schools, parents, or other members of the community. With both arrests and referrals, white youth are more likely to get off with a stern warning than Black or Latinx youth. Black youth are 2.3 times more likely to be arrested compared to white youth for the same behavior (Rovner, 2023b). Once they have been referred, there are two options: diversion or intake. Diversion is placing the youth in an alternative punishment for their behavior or dismissing the case altogether. Intake means to send the youth’s case into the court system, which means that the child now has a juvenile justice system record, no matter the outcome. These decisions are made by staff at the juvenile court, the district attorney’s office, or a probation officer. White youth are 29 percent more likely than Black youth to have their cases diverted (Rovner, 2023b).

After intake, the next decision is the seriousness of the charge. For some crimes, there is little flexibility in what to charge, but for most cases, there is a great deal of discretion. The prosecutor typically decides which charges to file and whether or not the youth should be charged as an adult and waived to the adult criminal justice system. Black youth are waived to adult court at a 72 percent higher rate than their white peers who are accused of the same offenses (Bryson and Peck, 2020).

For cases that are not dismissed, settled through diversion, or waived to adult court, youth are either held in a juvenile detention facility while they await the next steps (like an adult being held in jail while awaiting their trial), or they may be allowed to leave and spend this waiting period at home. This decision is made by the judge in the case, who determines whether the youth is dangerous or a flight risk. White youth are 50 percent more likely than youth of color to be considered safe and allowed to leave (Rovner, 2023b).

The next steps include adjudication (being found guilty by the court) and disposition (sentencing) (OJJDP, n.d.). Disposition options tend to include either probation or placement. Probation is most often awarded to white youth (Rovner, 2023b). Placement is incarcerating the youth in a corrections facility (like jail or prison, but for juveniles). Black youth are 4.4 times, Indigenous youth 3.2 times, and Latinx youth 1.3 times more likely to be incarcerated than their white peers (Rovner, 2023b).

Once the youth serves their disposition (sentence), they move on to aftercare. Although this is similar to parole for adults, there is more of a focus on helping the youth be successful to keep them from becoming involved in the criminal justice system as adults. We will talk more about aftercare later in this chapter.

Juvenile Corrections Facilities

Although long-term, secure juvenile corrections facilities are often called camps, schools, or academies, the fact is that they are a modified version of a prison for kids. The education offered is very often low-quality, particularly for students with special education needs (The IRIS Center, 2016). Often, there is very little mental health care or counseling to address previous traumas that contributed to their delinquent behavior in the first place. Youth can be kept in solitary confinement for minor infractions such as talking back. They must undergo strip searches, are often shackled with hand and ankle cuffs plus belly chains, can be sprayed with chemical sprays, and frequently undergo emotional, physical, and sexual abuse at the hands of both staff and other youth in the facility (Bernstein, 2014). Youth experience all of this in addition to being removed from family and friends while living in a facility far from home and full of other traumatized children.

Despite the focus on rehabilitation, most youth come out of juvenile corrections with new traumas and are likely to increase delinquent and criminal behavior both in frequency and level of violence (VanderPyl, 2018). Because youth of color are more likely to be incarcerated than their white peers, our juvenile justice system is compounding harm at a greater level for Black, Indigenous, and Latinx youth. This racist system also promotes a greater risk for future adult criminality, which in turn promotes greater incarceration rates for Black, Indigenous, and Latinx adults.

Programs and treatment within secure care facilities should have enough promise to interrupt these damaging trajectories; however, they differ by facility in selection, quality, and quantity. Also, much programming has been culturally ignorant and created by white scholars for white youth. In addition, issues of understaffing mean that facilities must rely on volunteers (who are few and hard to find) to deliver programming and treatment for the youth.

Age of Criminal Responsibility

Let’s go back to the discussion on youth being waived to adult court. The age of criminal responsibility in this country is 18 years old. That means for crimes that are considered “adult,” someone under the age of 18 would be moved over (or waived) to the adult court system so the criminal justice process could be handled there. The reasoning is that if a child is mature enough to commit an adult crime, they should be treated like an adult by the system.

The practice of charging kids as adults is another one that became popular in the 1990s, another reaction to that decade’s cultural panic around teens and violence. As mentioned earlier, in 1994, the Oregon state legislature proposed Measure 1,1, and voters passed it with 65 percent voting in favor. Under Measure 11, there are certain crimes for which a child as young as 15 will be automatically tried as an adult and, if found guilty, sentenced to a mandatory minimum sentence determined by the legislators who wrote the ballot measure. The list includes 21 crimes considered especially bad, and the sentences range from 5 years, 10 months, to 25 years. For these offenses, the age of criminal responsibility is lowered to 15 years old.

Although Measure 11 is relatively clear-cut, its application still has room for bias. The district attorney’s office is responsible for deciding whether or not a charge is filed as a Measure 11 offense. That means they can charge someone differently to avoid Measure 11 or threaten to use Measure 11 during coercive plea negotiations to scare youth into accepting a plea deal. The Oregon Criminal Justice Commission reported that Black men were charged with Measure 11 crimes at a rate more than four times that of white men. Also, Black men were more likely to go to prison for Measure 11 crimes than their white counterparts (Officer, McAlister, and Tallan, 2021).

Some argue this racial bias is adultification, which is the perception that Black children are older and less innocent than white children (Cooke and Halberstadt, 2021). Also, young Black boys are seen as bigger and more physically threatening than white boys of the same size (Wilson, Hugenberg, and Rule, 2017). They are also 1.27 times more likely to be perceived as angry compared to their white peers (Cooke and Halberstadt, 2021). This adultification helps justify more punishment for youth of color than their white peers to those making such discriminatory decisions.

Juvenile Life Sentences

Adultification may also play a role in why youth of color are disproportionately sentenced to die in prison. In some cases, the courts have determined a juvenile has “permanent incorrigibility” and cannot be saved. Juvenile life without parole (JLWOP) is a juvenile sentenced to life in prison without the possibility of parole. This is a true death sentence, and it is given to children, 62 percent of whom are Black (Rovner, 2023a). In states where JLWOP is unpopular, there are still sentencing options that make sure a particular juvenile will never get out. De facto or virtual life sentences contain so many years that the term of the sentence is beyond the person’s natural life expectancy. For example, consecutive sentences, where multiple sentences are added to each other, can add up to several decades, or even over 100 years. Roughly 1,700 people are serving such long sentences they received as children in this country, waiting out their deaths in prison, although not technically sentenced to die (Rovner, 2023a).

Learn More: JLWOP and Lionel Tate

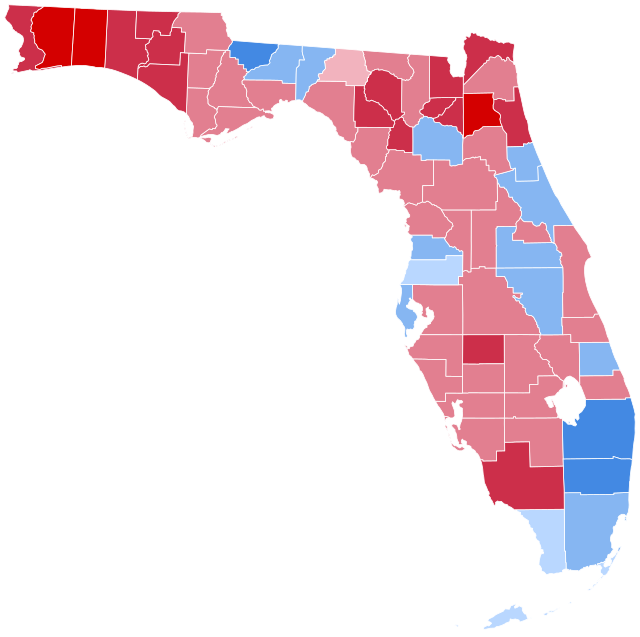

Florida holds the records both for the youngest children in the United States ever to be charged as adults (ages 12 and 13) in 1999 and for the youngest child to ever be sentenced to die in prison. Lionel Alexander Tate was sentenced to life in prison without the possibility of parole in 2001 when he was just 13 years old.

In 1999, Lionel was left alone briefly while playing with his 6-year-old cousin Tiffany. The two were allegedly roughhousing, and Lionel (who weighed 170 pounds) used what he said were wrestling moves on Tiffany (who weighed 48 pounds). The prosecution believed this was a case of aggravated child abuse that ended in the death of a child. Lionel was charged as an adult with first-degree murder. Despite Lionel and his mother’s claims that Tiffany’s death was a terrible accident caused by Lionel copying wrestling moves he had seen on television, he was found guilty of felony murder and given a mandatory life sentence.

After his conviction, even the prosecuting attorneys joined the outcry over his sentence. The judge has no discretion to modify the sentence under Florida law. The mandatory minimum sentence tied to the charge of first-degree murder meant the court could not take into account Lionel’s age or any other factors in assigning that sentence.

Juveniles and the Death Penalty

In 1976, the U.S. Supreme Court upheld the constitutionality of the death penalty in Gregg v. Georgia, even for juvenile offenders. Between 1976 and 2005, 22 people were executed in this country for crimes they committed at the ages of 16 and 17. Of the 22 executed, 55 percent were people of color (11 Black, 1 Latinx). Considering the first juvenile offender was executed in this country in 1642, it is alarming that it took until 2005 to see any reform in capital punishment for children (DPIC, n.d.).

In the 2005 case, Roper v. Simmons, the U.S. Supreme Court decided that we should no longer sentence children to the death penalty. Dying in prison was still allowed, just not at the hands of a sanctioned executioner. This ruling changed the sentences of 72 juvenile offenders on death row and converted them to JLWOP (Rovner, 2023a). Then, in 2010, the Supreme Court decided to back off the punishment of kids a little bit further in Graham v. Florida. Their decision in Graham limited JLWOP to only those with homicide convictions. This case gave hope to another 123 now-adults in prison who could now get a reasonable opportunity to be considered for release one day through the possibility of parole (Rovner, 2023a).

In 2012, the U.S. Supreme Court jointly decided on two cases, Miller v. Alabama and Jackson v. Hobbs, where they determined that even children (Miller and Jackson were both 14 at the time of the convictions) found guilty of murder should not be given mandatory life sentences either. This opened up new opportunities for roughly 2,500 now-adults in prison who were serving life sentences for homicide offenses they committed as children (Rovner, 2023a). These adults in custody now also had the hope of a chance at earning parole. However, not every state agreed to apply this ruling to people already serving these sentences. The Supreme Court intervened in 2016 with Montgomery v. Louisiana, where they ruled the Miller decision must be applied retroactively, and states were required to provide parole hearings for the roughly 2,100 people still in this situation (Rovner, 2023a). Everyone affected by these rulings can still be resentenced, and in all juvenile cases going forward, life without parole is still a valid sentence. These rulings merely removed the mandatory nature of such sentences. That means JLWOP still exists in 25 states (all others have removed it as a sentencing option), but it is no longer compulsory or automatically required.

Check Your Knowledge

Licenses and Attributions for During Juvenile Justice System Involvement

Open Content, Original

“During Juvenile Justice System Involvement” by Taryn VanderPyl, revised by Jessica René Peterson, is licensed under CC BY 4.0.

Figure 8.11. “Steps through the juvenile justice process” by Taryn VanderPyl is licensed under CC BY 4.0.

Open Content, Shared Previously

Figure 8.12. Photo of young men of color by Budgeron Bach is licensed under the Pexels License.

Figure 8.13. “Florida Presidential Election Results 2000” by Svenskbygderna is licensed under CC BY-SA 4.0.

a category of people grouped because they share inherited physical characteristics that are identifiable, such as skin color, hair texture, facial features, and stature

placing the youth in an alternative punishment for their behavior or dismissing the case altogether

to send the youth’s case into the court system, which means that the child now has a juvenile justice system record, no matter the outcome

found guilty by the court

sentencing

branch of the criminal legal system that controls the behavior of convicted persons including probation, parole, and incarceration

age at which an individual becomes legally responsible for criminal law violation through the adult court system

the perception that Black children are older and less innocent than white children resulting from racial bias (Cooke & Halberstadt, 2021)