9.3 The War on Drugs

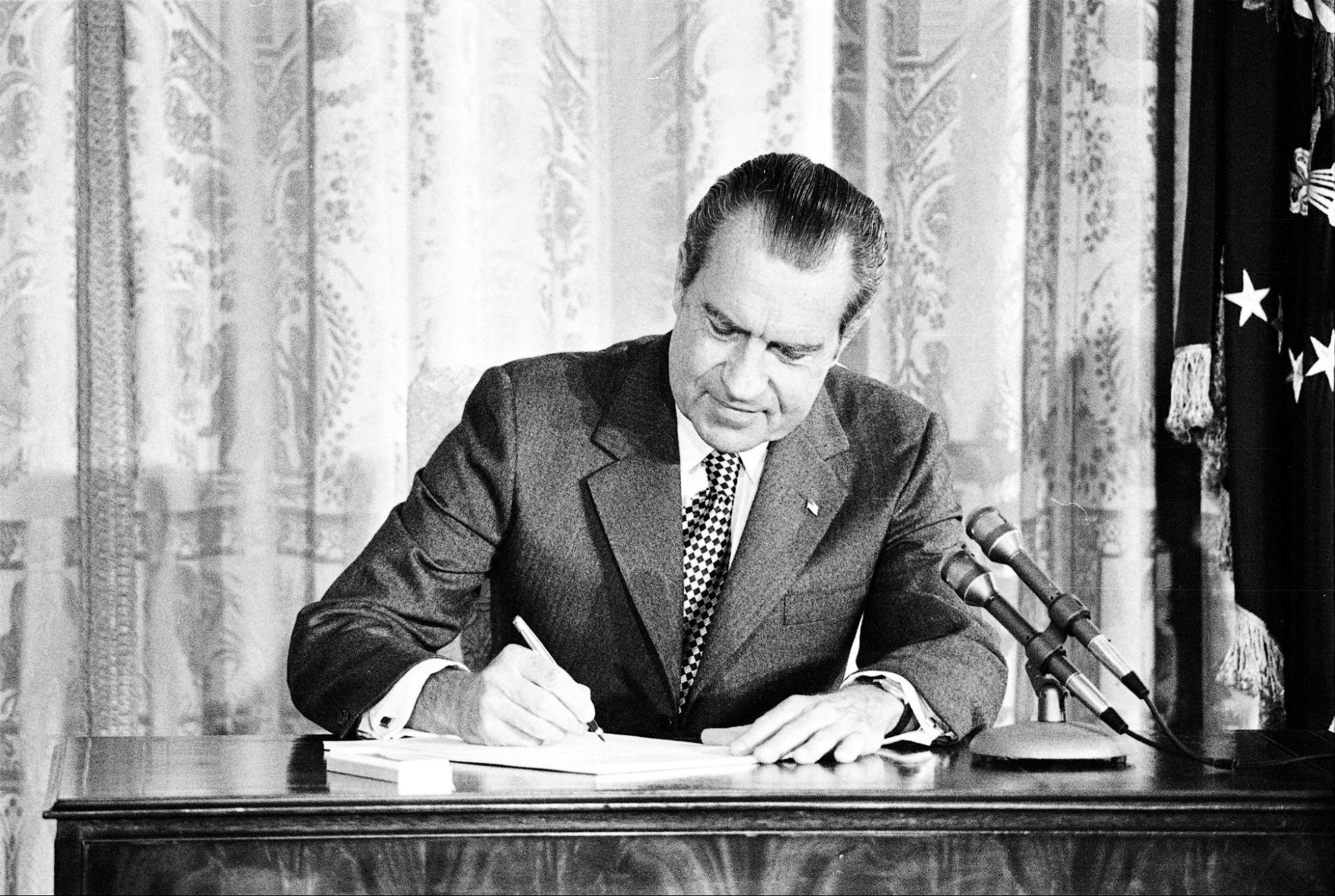

In 1971, President Richard Nixon declared a War on Drugs, dedicating increased federal funding and resources to quelling the supply of drugs in the United States. The War on Drugs greatly increased penalties, enforcement, and incarceration for drug offenders (Britannica, 2023). The hefty governmental spending to stop drug use also shifted our views on drug use and race. The United States became much more punitive toward drugs. The courts treated harmful drug use as a criminal justice issue, rather than as a substance dependence issue. The Drug Enforcement Agency was created in 1973 to provide another arm of the government to tackle the specific issue of drugs. By the 1980s, lengthy sentences for drug possession were also in place. One- to five-year sentences for possession were increased to upwards of 25 years.

This war continued to ramp up through the 1980s and 1990s, especially as crack cocaine became a growing concern in the media and public sphere. Crack cocaine was publicly portrayed as a highly addictive drug sweeping its way through America and destroying urban communities. This media portrayal allowed politicians to capitalize on public anxiety, along with pre-existing anti-Black racism, and pass policies that rapidly increased the prison population. The economic policies of the 1980s and 1990s, which worsened living conditions in urban centers such as Detroit, Chicago, Philadelphia, and Los Angeles, were not blamed for the destruction of communities – crack was. At this time, global economic shifts were sending manufacturing jobs overseas and succeeded in nearly eliminating the Black urban working class by the early 1990s (Trotter, 2019). These shifts, coupled with large cuts to state welfare benefits, led “vast numbers of Black people to seek other – sometimes ‘illegal’ – means of survival” (Davis as cited in Kendi and Blain, 2021). See the Learn More section below for research on the social and economic contexts of selling crack. The vast majority of arrests and enforcement were not of violent, high-level dealers. More often, police arrested small-time dealers or people struggling with addiction. In fact, during the 1990s, the period of the largest increase in the U.S. prison population, the vast majority of prison growth came from cannabis arrests (King and Mauer, 2006).

Learn More: When Selling Drugs May Be the Best Option

In Phillipe Bourgois’ book, In Search of Respect: Selling Crack in El Barrio (figure 9.3), Bourgois highlights the segregation and alienation of Puerto Ricans living in low-income 1980s New York communities. While interviewing, following, and documenting the Puerto Rican barrio residents, he finds many of them have faced extreme discrimination in their legal jobs. He talks about how many of them are sold on the idea of the “American Dream,” but they aren’t able to obtain it because of their background. Feeling anger at the system that prevents them from advancing in society, these young men are forced to seek power and respect in different ways. Many of these young Puerto Rican men resorted to selling crack to survive. Bourgeois’s book is an example of how political, economic, and cultural elements within the United States work against those who hold very little power. Understanding these large societal issues sheds light on the challenges faced by individuals living in poverty and the instances in which it might make more sense to break the law than follow it to survive. Living in poverty and experiencing racial and ethnic discrimination puts communities at a severe disadvantage and makes them vulnerable to further oppression. Providing systems in society that address the disadvantage of low-income BIPOC communities like the one described in Bourgois’ book by providing access to employment that provides a living wage and affordable housing could address this issue.

The War on Drugs as a War on People of Color

From the inception of the War on Drugs, racial biases were at the center of these policy changes. For instance, one of Richard Nixon’s top advisors, John Erlichman, explicitly admitted to this in a 2016 interview:

Do you want to know what this [War on Drugs] was all about? The Nixon campaign in 1968, and the Nixon White House after that, had two enemies: the antiwar left and [B]lack people. Do you understand what I’m saying? We knew we couldn’t make it illegal to be either against the war or [B]lack, but by getting the public to associate the hippies with marijuana and [B]lacks with heroin, and then criminalizing both heavily, we could disrupt those communities. We could arrest their leaders, raid their homes, break up their meetings, and vilify them night after night on the evening news. Did we know we were lying about the drugs? Of course, we did (Baum, 2016).

A sociological perspective that carefully examined white supremacy and related systemic racism would have helped better explain the crack epidemic. This perspective would have given rise to more humane responses, such as treatment instead of incarceration. Increases in problematic drug use and drug-related violence would be recognized as an indicator that something was wrong in America. Instead of examining the ways 350 years of white supremacy created suffering among Black communities, politicians and the media chose to vilify those who suffered from the accumulated disadvantages of things like convict leasing, lynching, redlining, school segregation, and lead in drinking water (Forman as cited in Kendi and Blain, 2021). “Instead of asking ‘What kind of people are they that would use and sell drugs?’ the nation should have been asking a question that, to this day, demands an answer: ‘What kind of people are we that build prisons while closing treatment centers?’” (ibid., 2021:354).

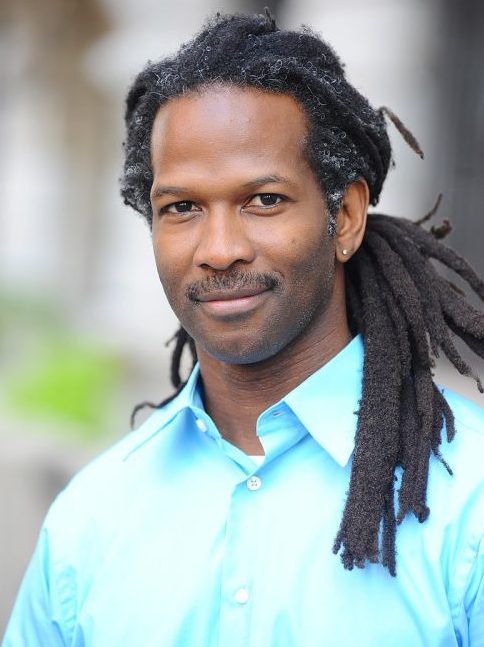

Learn More: Carl Hart and Understanding How Social Environments Cause Drug Use

Dr. Carl Hart (figure 9.6) was born in Miami, Florida, where he experienced firsthand the effects of the crack epidemic on his community. Growing up, he engaged in selling drugs and kept guns. He earned a Ph.D. in neuroscience from the University of Wyoming in 1996. His work focuses on drug use and the effects they have on one’s behavior and brain. Through his research, he highlighted how one’s environment plays a major role when becoming dependent on drugs. Dr. Hart is an advocate for how poverty and the criminalization of drugs are attributed to certain Black communities’ suffering, not the drugs themselves (Anthony, 2021). This shows us that drug policies that criminalize drug use may not be the solution to problematic drug use. Instead, sociologists look to the environment surrounding the individual, as well as their life circumstances, to understand how and why drug use may become problematic.

Mass Incarceration and the War on Drugs

The War on Drugs and its associated policies also drove massive increases in prison populations. Between 1980 and 2010, the U.S. prison population quintupled. The population only began to decline slightly in the early 2010s. As of 2019, the United States imprisoned more than 2 million people in prisons and jails. The United States has the largest prison population rate and the largest number of people incarcerated in the world. In the United States, the prison population rate is 629 people per 100,000. Canada’s rate is 104, and the United Kingdom’s (including only England and Wales) is 131 (Fair and Walmsley, 2021).

A disparity in drug possession sentencing policies during the 1980s and 1990s had the effect of funneling more BIPOC individuals into prison for longer sentences. Troyer (2021) drew a connection between the drastic incarceration of Black men and the fact that this demographic was not representative of Reagan’s voter base to suggest that incarceration was used as a tool for voter suppression. Six months after Reagan’s reelection, the Comprehensive Crime Control Act of 1984 was passed. Title V of this act increased the fine levels for drug trafficking, increased the penalties for trafficking in large amounts of controlled substances, provided increased penalties for distributing controlled substances in or near a school, and many more (U.S. Congress. Senate. Comprehensive Crime Control Act of 1984. S. 1762. 98th Cong., 1st sess. Introduced in House August 4, 1983).

During the height of the War on Drugs, the sentencing for crack cocaine and powder cocaine was made significantly different by the passage of the Anti-Drug Abuse Act of 1986. Powder cocaine is more likely to be used by wealthier people, who are disproportionately white (Vagins and McCurdy, 2006). Distributing 5 grams of crack cocaine had a five-year mandatory minimum federal prison sentence, while distributing 500 grams of powder cocaine had the same sentence. In 2002, more than 80 percent of crack cocaine defendants were Black, even though around 66 percent of the crack cocaine users were white or Hispanic (The Sentencing Project, 2004). If you are interested in media that explores the crack epidemic, you can watch the documentary Crack: Cocaine, Corruption, and Conspiracy, which can be found in the Chapter Resources.

The “Crack Baby” Epidemic

During the crack epidemic, a drug scare involving babies born to mothers who had used crack emerged. The media used now-invalidated research that expressed concern for the long-term cognitive and behavioral development of babies whose mothers had used crack while pregnant. Some states passed laws to criminalize the ingestion of some substances while pregnant, reasoning that it was akin to child maltreatment. Since Black mothers are more often under the watchful eye of governmental organizations, such as the child welfare system (Roberts, 2002), it was Black women who disproportionately suffered the inhumane consequences of these state laws (Roberts, 1997), as well as widespread public disapproval.

Later research showed the impacts on babies exposed to crack cocaine in utero were small. Barry M. Lester, a professor of psychiatry who directed a large federally funded study on children exposed to cocaine in the womb, stated that differences in brain development and behavior between children who were and were not exposed to cocaine in the womb were small (Okie, 2009). The ingestion of crack cocaine while pregnant did not meaningfully impact the children who were born. It was more often the conditions of poverty, including malnourishment and lack of prenatal care, that impacted babies born to crack-using mothers (Reinarman and Levine, 1997).

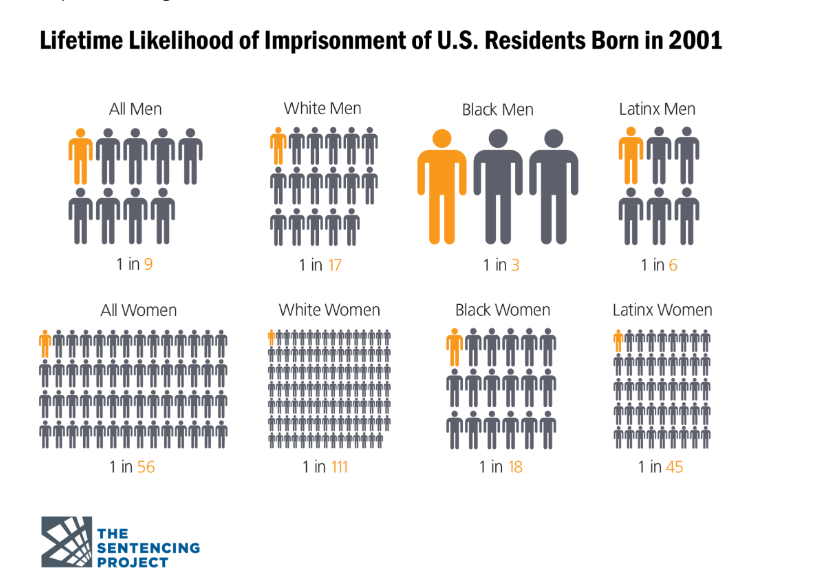

The War on Drugs was a deliberately racist set of policies that greatly increased the number of BIPOC individuals who have gone to jail or prison. Even though illegal drug use is more common among white people than among Blacks and Latinx people, the arrest rate for drug offenses is 10 times higher for Blacks than the rate for white people (Blow, 2011). Partly because of the drug war, about one-third of young Black men have prison records. Politicians often say that one in three Black men will end up in jail. More recent research suggests that this rate is declining, but the rate of incarceration remains disproportionately high (Kessler, 2015). Harsh drug laws and racism are intertwined such that “The ‘War on Drugs’ has become the primary social control mechanism legitimating the surveillance and punishment of African-American communities” (Sudbury, 2013:xxii). For a better understanding of the so-called “crack baby epidemic,” you can watch “Crack Babies: A Tale from the Drug Wars” in the Chapter Resources.

Check Your Knowledge

Licenses and Attributions for The War on Drugs

Open Content, Original

“The War on Drugs” by Kelly Szott and Kimberly Puttman, revised by Jessica René Peterson, is licensed under CC BY 4.0.

“Learn More: Carl Hart and Understanding How Social Environments Cause Drug Use” by Catherine Venegas-Garcia is licensed under CC BY 4.0.

Open Content, Shared Previously

Some paragraphs from “The War on Drugs” are adapted from “Harmful Drug Use: Exploring Unequal Outcomes” by Kelly Szott and Kimberly Puttman, in Inequality and Interdependence: Social Problems and Social Justice, which is licensed under CC BY 4.0.

“Mass Incarceration and the War on Drugs” is adapted from “Race, Identity, and the Criminal Justice System” by Alexandra Olsen, in Sociology in Everyday Life, which is licensed under CC BY 4.0. Modifications by Jessica René Peterson, licensed under CC BY 4.0, include light editing for relevancy.

“New Jim Crow” definition is from “Mass Incarceration and the New Jim Crow” by Alexandra Olsen, in Sociology in Everyday Life, which is licensed under CC BY 4.0.

Figure 9.2. “President Nixon signing the Drug Abuse Office and Treatment Act of 1972” by the White House Photo Office is in the Public Domain.

All Rights Reserved Content

Figure 9.3. Cover image of In Search of Respect: Selling Crack in the Barrio by Philippe Bourgois, © Cambridge University Press, is included under fair use.

Figure 9.4. Image by Students for Sensible Drug Policy is included under fair use.

Figure 9.5. “Lecture and discussion” by Columbia GSAPP is licensed under CC BY 2.0.

Figure 9.6. Carl Hart by Eileen Barroso, Simon Fraser University, is licensed under CC BY 2.0.

Figure 9.7. Lifetime Likelihood of Imprisonment of U.S. Residents Born in 2001 © The Sentencing Project is included under fair use.

Figure 9.8. Image included under fair use.

an effort in the United States since the 1970s to combat illegal drug use by greatly increasing penalties, enforcement, and incarceration for drug offenders (Britannica 2023).

a category of people grouped because they share inherited physical characteristics that are identifiable, such as skin color, hair texture, facial features, and stature

a form of prejudice that refers to a set of negative attitudes, beliefs, and judgments about whole categories of people, and about individual members of those categories because of their perceived race and ethnicity.

rules a person must follow during probation

the unfair treatment of marginalized groups, resulting from the implementation of biases, and often reinforced by existing social processes that disadvantage racial minorities

a group of people living in a defined geographic area that has a common culture

the racist belief that white people are superior to people of other races and ethnicities

refers to how racism is embedded in the fabric of society and how institutional processes are used to maintain systematic discrimination through the complex interactions of large scale societal systems, practices, ideologies, and programs that produce and perpetuate inequities for racial minorities. Also referred to as institutional or structural racism.

organized action intended to change people’s behavior (Innes 2003).