9.4 The Opioid Crisis and Race

Another way to notice racism at work in response to harmful drug use is to examine the opioid crisis. The opioid crisis refers to the surge in fatal overdoses linked to opioid use (DeWeerdt, 2019). The overdose fatality rate rose by 345 percent between 2001 and 2016 (Jalali et al., 2020). Opioids are a class of drugs that cause euphoria. Opioids include heroin, morphine, codeine, hydrocodone, OxyContin, and fentanyl (Johns Hopkins Medicine, 2023). Heroin is an illegal drug. The others are prescription drugs that doctors prescribe for pain relief.

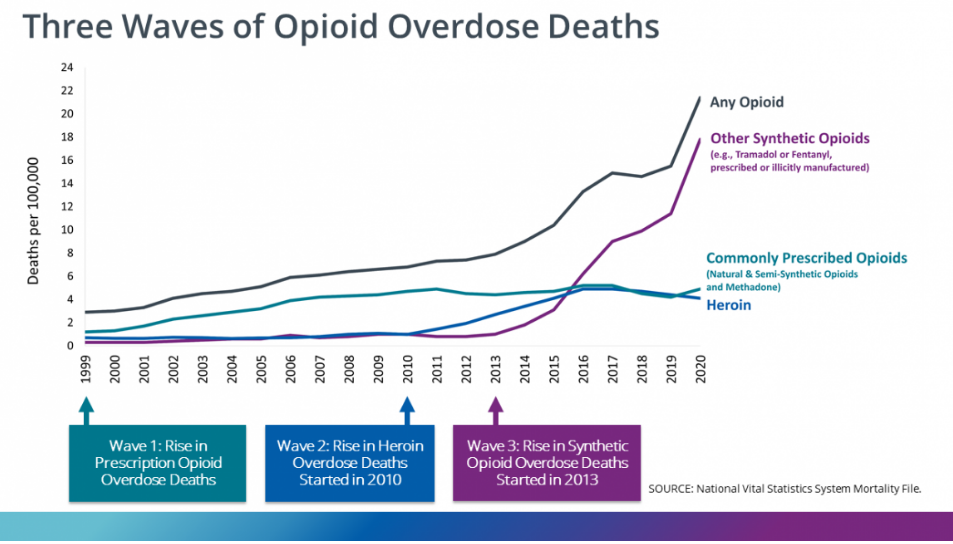

Nearly 75 percent of drug overdoses in 2020 involved a legal or illegal opioid (CDC, 2022). The CDC describes the crisis using three waves. The first wave started in the 1990s. In this wave, the deaths were primarily due to overdoses on prescription opioids, like OxyContin and Vicodin. This wave was a result of the overprescription of opioid-based painkillers, causing some individuals to become physically dependent. Interestingly, the BIPOC community was somewhat protected from the over-prescribing of opioid painkillers due to institutional racism in the medical system. Research has documented that Black patients’ health concerns are frequently ignored or minimized by healthcare practitioners. Black patients are less likely to be prescribed adequate amounts of medication to treat their pain (Anderson, Green, & Payne, 2009).

The second wave started in 2010. The second wave was due to overdoses related to using heroin. This use of heroin partially resulted from a decrease in the amount of legally available prescription painkillers. The third wave started in 2013. This wave marked an increase in overdose deaths from synthetic opioids like fentanyl and tramadol. While fentanyl can be prescribed, this wave was driven by illegally manufactured substances. As of May 2023, 106,539 drug overdose deaths had been reported for the prior year in the United States (CDC, 2023). Around 75,000 of those deaths are attributed to synthetic opioids such as fentanyl (Weiland, 2023).

The War on Drugs During the Opioid Crisis

The societal response to opioid use and dependence among white people during this crisis has been gentler, relying more on treatment than the criminal justice system (Hart and Hart, 2019; James and Jordan, 2018). According to statistics from the Bureau of Justice Statistics, 80 percent of arrests for heroin trafficking are among Black and Latinx people, even though white people use heroin at higher rates and are known to purchase drugs within their racial community (James and Jordan, 2018).

In researching the societal response to the opioid crisis, social science scholars proposed the idea of “white opioids” (Netherland and Hansen, 2017). They note how the societal response to the opioid crisis has reinforced racial inequalities and racialized drugs by decriminalizing and medicalizing the sphere of opioid use by white people and continuing to criminalize and control the sphere of opioid use by Black communities. They state that the legal opioids OxyContin and Suboxone (the brand name for buprenorphine) are white. The less desirable medication for opioid use disorder (MOUD), methadone, has been racialized as predominantly used by BIPOC. Methadone treatment is a more controlled, rigid, and public form of MOUD than Suboxone/buprenorphine. The societal and medical response to the opioid crisis has been highly racialized, with BIPOC disproportionately bearing the more negative effects (Netherland and Hansen, 2017).

As we examine the response to the overprescription of opioids and the harmful use of fentanyl, we see a stark difference in public response. We see a focus on monitoring doctors, so that they don’t overprescribe opioids. We see a focus on overuse of opioids as a medical disease needing treatment, rather than criminalizing the user of the drug. Our response to drug overuse in the opioid crisis is racialized.

The public response to the use of opioids by white people has been different from the public response to the use of crack cocaine by Black and Brown communities in the 1980s and 1990s. The new so-called drug war that focuses on the use of opioids by white people has been much gentler than the implementation of the drug war in the late 20th century. The “white drug war” is less punitive and found in the clinical realm, where opioid use is essentially decriminalized and where drug use is seen as a biomedical disease. In this way, white social privilege is preserved.

The treatment of opioid use shows evidence of racial discrimination with white people who use opioids gaining access to buprenorphine in a private doctor’s office, while Black and Brown users of opioids are left to receive treatment in stigmatized methadone clinics (Netherland, 2015). Politicians legalized buprenorphine treatments for opioid use disorder (such as Suboxone or Subutex), in part due to a belief that white middle-class opioid users needed a more private space for treatment. A protected and private space has been created for white people, while Brown and Black people who use opioids still deal with the punitive and carceral approach toward drug use (Netherland and Hansen, 2017).

Overdose Deaths and Race

The opioid crisis is a crisis of overdose deaths. The rates of those fatalities are stratified unequally by race. From 2019 to 2020, the largest increase in drug overdose deaths was among Black people. The increase was 44 percent compared to 20 percent for white people. The overall rate of increase from 2019 to 2020 was 30 percent. Astoundingly, the increase in overdose deaths of Black people ages 15 to 24 was 86 percent. It was 34 percent for white people in that age group. The increase in overdose deaths from 2019 to 2020 was largely driven by fentanyl in the illicit drug supply (Kariisa et al., 2022). If you would like to learn more, particularly about the explanation offered by a medical doctor of increased overdose death among Black communities when fentanyl enters the illicit drug supply, you can watch the “Addicted and Left Behind” video in the Chapter Resources.

Health harms caused by substance use are higher, and drug overdose rates have increased faster among Black people who use drugs, not because they participate in riskier drug use behavior, but because they are more likely to reside in under-resourced communities that hinder access to health-promoting services and materials (Cooper et al., 2011). Accordingly, opioid overdose rates for Black people have historically been higher than those for white people in some states. Recently, this rate has been increasing more rapidly, though the media attention surrounding the opioid crisis mostly focuses on drug use by white people (James and Jordan, 2018).

Learn More: The Crimes of the Sackler Family

The opioid medication widely believed to have started the opioid crisis is OxyContin. It was first released in 1996 by the pharmaceutical company Purdue Pharma. At that time, the Sackler family owned and largely directed the company. The Sacklers are a wealthy white family who have made billions from their sales of OxyContin. Many have likened the Sackler family to drug dealers and questioned why they are not prosecuted as such (Macy, 2022; McGreal, 2019). The Sackler family has committed something akin to white-collar crime, though one might consider their crime violent since lives were lost due to opioid overdose. Protected by their wealth and white privilege, the Sackler family, as you will read below, has successfully avoided legal responsibility for the opioid crisis and remains extremely wealthy to this day. The Sackler family’s avoidance of accountability and continued wealth and freedom – they are not incarcerated – serve as an example of how drug policy works differently for the white wealthy class than it does for BIPOC communities.

Purdue Pharma used aggressive and deceptive tactics to advertise OxyContin to physicians and other prescribers. Purdue sales representatives earned large bonuses for meeting the sales quotas of OxyContin (Quinones, 2015). Using findings from a very small and unrepresentative medical study of hospital patients receiving opioids to treat pain, Purdue instructed its sales reps to state that OxyContin was only addictive to less than 1 percent of patients, which is not accurate. Furthermore, Purdue created physician education programs that provided “misleading and incomplete scientific evidence about OxyContin” (Bazerman, 2022:19). In 2006, Purdue Pharma was charged with criminal misbranding because it knowingly trained its staff using inaccurate information about OxyContin (Quinones, 2015). Purdue agreed to a plea deal and paid $634.5 million in fines – a relatively small portion of their wealth.

If you want to learn more, watch the “OxyContin Patients, Then and Now” video showing the OxyContin advertising campaign that positions it as a safe and effective medication, as well as advocates for more aggressive treatment of pain. You can find it in the Chapter Resources.

The Sackler family has long denied their responsibility in facilitating the opioid crisis. They have also spoken in negative ways about people addicted to opioids, blaming them individually for the large social crisis of opioid misuse and disparaging them as “abusers.” Richard Sackler states,,d “We have to hammer on the abusers in every way possible” as a strategy of avoiding blame for Purdue (Macy, 2022:xviii). The owners of Purdue Pharma blame heroin and fentanyl for the opioid crisis, rather than OxyContin (McGreal, 2019). In 2019, the Sackler family shielded themselves from further accusations of wrongdoing by declaring bankruptcy. Meanwhile, they had shifted $10 billion of Purdue Pharma money to family trusts and offshore accounts (Macy, 2022). The terms of the bankruptcy filing ensured that the Sackler family was immune from any further civil litigation regarding OxyContin and the opioid crisis.

There were over 2,000 court cases filed against the Sackler family and Purdue Pharma by cities, states, and Indigenous Tribes deeply impacted by the opioid crisis. All of these cases will be dropped because the Sackler family has been allowed full immunity by the judge overseeing their bankruptcy proceedings (Macy, 2022). As of May 2023, the Sacklers had agreed to pay $6 billion, which will be used by states and cities to address the opioid crisis, in exchange for immunity (Delouya, 2023).

Check Your Knowledge

Licenses and Attributions for The Opioid Crisis and Race

Open Content, Original

“Overdose Deaths and Race” by Kelly Szott is licensed under CC BY 4.0.

“Learn More: The Crimes of the Sackler Family” by Kelly Szott is licensed under CC BY 4.0.

Open Content, Shared Previously

Last paragraph of “Overdose Deaths and Race” is adapted from “Harmful Drug Use: Exploring Unequal Outcomes” by Kelly Szott and Kimberly Puttman, in Inequality and Interdependence: Social Problems and Social Justice, which is licensed under CC BY 4.0. Modifications by Kelly Szott, licensed CC BY 4.0, include remixing with original content.

Figure 9.9. “Three Waves of Opioid Overdose Deaths” from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention is in the Public Domain.

Figure 9.10. “OxyContin branded oxycodone 10mg” by Psiĥedelisto is in the Public Domain, CC0 1.0.

a form of prejudice that refers to a set of negative attitudes, beliefs, and judgments about whole categories of people, and about individual members of those categories because of their perceived race and ethnicity.

refers to the surge in fatal overdoses linked to opioid use (DeWeerdt 2019)

decriminalizing and medicalizing the sphere of opioid use by white people and continuing to criminalize and control the sphere of opioid use by Black communities.

the unfair treatment of marginalized groups, resulting from the implementation of biases, and often reinforced by existing social processes that disadvantage racial minorities

a category of people grouped because they share inherited physical characteristics that are identifiable, such as skin color, hair texture, facial features, and stature

the special benefits, protections, and access to the power conferred onto white people

refers to the procedures used by our government to control the use and sales of psychoactive substances, particularly those that are addictive