9.5 Drug Policy Reform and Liberatory Harm Reduction

Harm reduction services and policies focus on people who use drugs or participate in risky activities with information and tools to reduce their risks while participating in these activities. Similar harm reduction strategies are wearing seat belts or providing adolescents with condoms.

One of the most well-known harm reduction practices is syringe exchange, which became legal during the HIV epidemic of the 1980s and 1990s. Its goal was to help people who inject drugs avoid infection with the virus. Currently, harm reduction is also associated with the distribution of the opioid overdose reversal antidote Narcan, or naloxone. This medication can almost instantaneously reverse an opioid overdose, saving a person’s life.

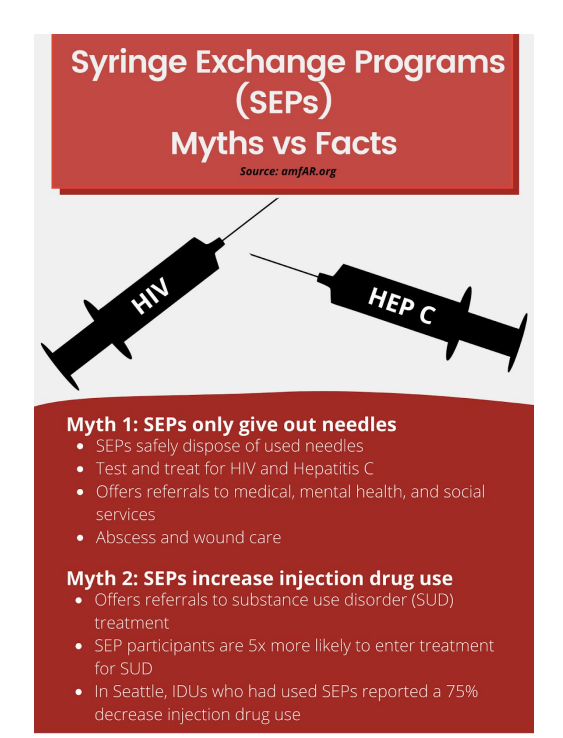

Some critics believe that harm reduction policies enable drug use. There is no scientific evidence to support this idea. Instead, syringe exchange reduces HIV and hepatitis C rates, and the distribution of Narcan lowers drug overdose mortality rates (Platt et al., 2018; Fernandes et al., 2017; Chimbar and Moleta, 2018).

Harm reduction uses a grassroots approach based on advocacy from and for people who use drugs and accepts alternatives to abstinence that reduce harm (Marlatt, 1996). According to the Harm Reduction Coalition, a core principle of harm reduction philosophy, “accepts for better or worse, that licit and illicit drug use is part of our world and chooses to work to minimize its harmful effects rather than simply ignore or condemn them.” Harm reduction revolutionizes how we respond to human problems like addiction, drug overdose, and HIV.

Harm reduction is also a social justice movement. This is where liberatory harm reduction comes in. Anti-racist, anti-violence, prison abolitionist activists are rightfully urging that the true roots of the harm reduction approach be recognized as residing in the practices of BIPOC “who were sex workers, queer, transgender, using drugs, young people, people with disabilities and chronic illness, street-based, and sometimes houseless” (Hassan, 2022). Groups fighting the oppressive structures of our society, such as capitalism, cisgenderism, heterosexism, patriarchy, ableism, and settler colonialism, laid the foundation for the harm reduction movement as we know it today.

Queer femme of color, Shira Hassan, who was a former sex worker and drug user, and also has worked for years as an anti-racist, anti-violence fighter of oppression, defines liberatory harm reduction as “a philosophy and set of empowerment-based practices that teaches how to accompany each other as we transform the root causes of harm in our lives” (2022:29). Liberatory harm reductionists put their values into practice by using practical strategies to reduce the negative health, legal, and other social consequences of criminalized and stigmatized life experiences. These experiences can involve sex work, drug use, surviving intimate partner violence, self-injury, eating disorders, and any other survival practices that society deems immoral. Importantly, liberatory harm reductionists provide support without judgment, stigma, or coercion. They do not force others to change. Liberatory Harm Reduction “is true self-determination and total body autonomy” (Hassan, 2022:29).

Liberatory harm reduction diverges from standard public health policies of harm reduction by actively calling out and fighting against all forms of oppression, focusing on relationships of radical non-judgement, and complete body autonomy (Hassan, 2022). Hassan writes: “Safety is created through the investment we make in each other and the acceptance and holding we offer in a world that wants to see us dead or locked up” (2022:32–33).

Questioning Harm Reduction

At first, Black and Brown communities were suspicious of harm reduction programs and policies because of the outsized negative impacts of the War on Drugs on them. Historically, Black and Brown communities have a greater distrust of public health programs due to government programs like the Tuskegee Syphilis Study, which allowed Black men to suffer untreated through syphilis, even when there were known treatments. The first syringe exchange program opened in New York City in 1989, and the Black community felt that it was “evidence of the city’s unwillingness to allocate the necessary resources to support drug treatment programs” (Woods, 1998). The Black community also felt that harm reduction was a “half-hearted, insincere, unrealistic, and racist” attempt to convince them to lower their expectations and accept their deterioration (Woods, 1998:315).

Woods, herself a Black woman, writes that drug use was seen as a characteristic of those who are considered a disgrace to the race. Black communities and individuals suffer disproportionately from an array of drug-related adverse effects: less access to health care, unemployment, and incarceration. Black communities have often been the “distribution ground” for illicit substances (Woods, 1998:309). This associates Blacks with illicit activities and desire, and thus, they suffer the stigma and the consequences of selling drugs.

Woods (1998) is an advocate for harm reduction and syringe exchange. She believes we must embark on an educational program to deal with miseducation about substance use. A view of drug use as immoral is built into our government policies. It must, instead, be seen as a public health issue, and harm reduction programs for Black communities must be created by them (Woods, 1998).

More recent research on harm reduction programs in Black communities has found that the harm reduction movement’s new focus on the overdose epidemic elicited indignation and annoyance from some community members because they felt that for decades their experiences with overdose had been ignored or discredited (Lopez et al., 2022). It seemed that it was only after white communities started experiencing the impacts of overdose that resources were quickly distributed (Lopez et al., 2022).

Black and Latinx leaders of harm reduction and substance use treatment programs are calling for the need to have BIPOC leadership in harm reduction organizations and policy creation. BIPOC leaders will center the perspectives of racialized groups, use personal experience to relate to and build trust with community members, and inform policy and program development with their perspectives as part of a racialized community (Hughes et al., 2022). These leaders recognize that law enforcement practices that target BIPOC communities and spaces, among other things, are linked to high rates of substance overdose deaths (Hughes et al., 2022).

Legalization of Cannabis

The movement to decriminalize and legalize cannabis in the United States has been motivated by the nation’s long history of systemic racism and the War on Drugs. To decriminalize something means that it is still against the law, but violations usually result only in a ticket. Since 2012, 23 states and Washington, D.C., have legalized cannabis for adults over the age of 21. Legalizing cannabis has meant fewer arrests and less jail time. In Oregon, the number of cannabis arrests decreased by 96 percent from 2013 to 2016, the year cannabis was legalized for adult recreational use (The Drug Policy Alliance, 2022).

The Drug Policy Alliance, a nonprofit organization that advocates for the decriminalization of drugs, examined rates of youth cannabis use. They found that since the legalization of cannabis use in some states, youth use rates have remained stable and in some cases even gone down. They have also found that legalization has not made roadways less safe due to driving under the influence (of cannabis). Finally, they show that states are using the money generated through taxes on legal cannabis for the social good (The Drug Policy Alliance, 2022). In Oregon, 40 percent of the cannabis tax revenue goes to the state school fund, and 20 percent goes to alcohol and drug treatment.

Youth involvement in the juvenile justice system can have long-lasting negative impacts on the life outcomes of youth. When considering whether marijuana should be legal, Hammond et al. (2020) point out that we must balance the negative impacts on youth brain development and motor vehicle accidents with the positive effects of decriminalization, reducing youth juvenile justice involvement. For example, involvement in the juvenile justice system may disrupt education or cause long-lasting mental health problems. Further, we know that BIPOC are disproportionately impacted by the criminal justice system. We must consider the reduction of these types of issues alongside the known negative impacts of youth cannabis use.

Equity and Cannabis Industry Participation

Another equity issue arises with the legalization of cannabis and the rise of a money-making industry. A drug-related felony on an individual’s record may be a barrier to gaining a license to sell cannabis through a dispensary (see figure 9.12). As we’ve discussed in this chapter, due to systemic racism within drug policy enforcement, those with drug-related felonies on their record are disproportionately Black. This means that Black entrepreneurs may be disproportionately blocked from entering the cannabis industry.

Several states and cities have implemented equity programs to address the issue of BIPOC being prevented from participating in the cannabis industry due to past felony convictions. In California, a prior drug felony cannot be the sole basis for denying a cannabis license. In Portland, Oregon, a portion of cannabis sales tax revenue is spent on funding women-owned and minority-owned cannabis businesses (The Drug Policy Alliance, 2022). Portland also has a social equity program that gives fee reductions and reimbursements to cannabis businesses that contract with minority-owned businesses and/or have staff or owners with prior cannabis convictions (City of Portland, Oregon, n.d.).

Learn More: Measure 110 in Oregon

On November 3, 2020, Oregon became the first state in the United States to decriminalize the personal possession of illegal drugs. By approving Measure 110, Oregon voters significantly changed the way drug possession violations are addressed. People found with smaller amounts of controlled substances (such as heroin, cocaine, or methamphetamine) are issued a Class E violation, which is punishable by a $100 fine. Alternatively, people in violation can have the fine waived if they complete a health assessment at an addiction recovery center.

Measure 110 also created a new drug addiction treatment and recovery grant program funded by the anticipated savings due to reduced enforcement of criminal drug possession penalties, as well as cannabis sales tax revenues (Lantz and Neiubuurt, 2020). This law shifted the societal response to drug use from a punitive, moralistic approach to one that involved treatment and compassion.

Advocates for Measure 110 saw it as a way to eliminate drug policies that had a disproportionately negative impact on Black and Indigenous people of color. Arrests are often a person who uses drugs’ first exposure to the criminal legal system. These arrests have negative health and social consequences. Reducing exposure to the criminal justice system is a goal for racial equity in and of itself (Russoniello et al., 2023). An analysis by Oregon’s Criminal Justice Commission (2020; as cited in Russoniello et al., 2023) estimated that Measure 110 will reduce misdemeanor and felony convictions for possession of controlled substances among Black and Indigenous communities by 95 percent.

Oregon’s decriminalization of low-level drug offenses is revolutionary, but it follows the advice of national social justice advocates. To address the racial and ethnic disparities in criminal justice systems, Ashley Nellis from the Sentencing Project recommends:

Discontinue arrest and prosecutions for low-level drug offenses, which often lead to the accumulation of prior convictions that disproportionately accumulate in communities of color. These convictions generally drive further and deeper involvement in the criminal legal system (Nellis, 2021).

Decreasing criminal involvement due to drug use is one way of reducing racial oppression in the criminal justice system. Measure 110 involves treating harmful drug use as a possible behavioral health issue, rather than a criminal condition that needs punishment.

Note: During the development of this book, Measure 110 was modified and possession of controlled substances was re-criminalized by House Bill 4002, which became effective in September 2024. The full impacts and results of the measure are not yet known.

Check Your Knowledge

Licenses and Attributions for Drug Policy Reform and Liberatory Harm Reduction

Open Content, Shared Previously

“Drug Policy Reform and Liberatory Harm Reduction” is adapted from “Harmful Drug Use: Exploring Unequal Outcomes” by Kelly Szott and Kimberly Puttman, in Inequality and Interdependence: Social Problems and Social Justice, which is licensed under CC BY 4.0. Modifications by Kelly Szott, revised by Jessica René Peterson, which are licensed under CC BY 4.0, including copying, adapting, and adding original content.

“Legalization of Cannabis” is adapted from “Harmful Drug Use: Exploring Unequal Outcomes” by Kelly Szott and Kimberly Puttman, in Inequality and Interdependence: Social Problems and Social Justice, which is licensed under CC BY 4.0. Modifications by Kelly Szott, revised by Jessica René Peterson, which are licensed under CC BY 4.0, include removing some paragraphs.

“Learn More: Measure 110 in Oregon” is adapted from “Harmful Drug Use: Exploring Unequal Outcomes” by Kelly Szott and Kimberly Puttman, in Inequality and Interdependence: Social Problems and Social Justice, which is licensed under CC BY 4.0. Modifications by Kelly Szott, revised by Jessica René Peterson, which are licensed under CC BY 4.0, include light editing, reorganization, and expanding the first paragraph of “Racial Justice Underpinnings.”

All Rights Reserved Content

Figure 9.11. “Syringe Exchange Programs” by the American Medical Student Association is included under fair use.

Figure 9.12. “What Is the Drug War? Jay-Z and Molly Crabapple” by Drug Policy Alliance is licensed under the Standard YouTube License.

Figure 9.13. “Stop the Drug War Artistic Collage” by DMTrott is licensed under CC BY 4.0.

focuses on providing people who use drugs or participate in risky activities with the information and material tools to reduce their risks while participating in these activities.

a philosophy and set of empowerment-based practices that teach us how to accompany each other as we transform the root causes of harm in our lives. It is true self-determination and total body autonomy.

a group of people living in a defined geographic area that has a common culture

an effort in the United States since the 1970s to combat illegal drug use by greatly increasing penalties, enforcement, and incarceration for drug offenders (Britannica 2023).

a category of people grouped because they share inherited physical characteristics that are identifiable, such as skin color, hair texture, facial features, and stature

refers to how racism is embedded in the fabric of society and how institutional processes are used to maintain systematic discrimination through the complex interactions of large scale societal systems, practices, ideologies, and programs that produce and perpetuate inequities for racial minorities. Also referred to as institutional or structural racism.

refers to the procedures used by our government to control the use and sales of psychoactive substances, particularly those that are addictive

something is still against the law, but violations usually result only in a ticket.

a form of prejudice that refers to a set of negative attitudes, beliefs, and judgments about whole categories of people, and about individual members of those categories because of their perceived race and ethnicity.