5.3 Reducing Police Encounters: Crisis Response Systems

Anne Nichol

One important way to improve crisis outcomes is to minimize or avoid police involvement in resolving crises. The primary way to accomplish this broad goal is to build and support a behavioral health crisis response system that is outside of the criminal justice system. A crisis response system is, simply, a way to respond to crises that includes three core elements: someone to call, people to respond, and a place to go (SAMHSA, 2023b). Where a functional behavioral health-focused crisis response system is in place, those elements are not satisfied by what many communities rely on now: 911, the police, and jail. Rather, these core elements are addressed by crisis lines or call centers, mobile crisis teams, and crisis stabilization centers (SAMHSA, 2023b). This section provides an overview of these approaches being explored nationally and locally in U.S. communities (figure 5.6).

As a reminder, the term behavioral health was introduced in Chapter 1 of this text as a very broad term that includes care for and responses to mental disorders as well as various other forms of support around emotions, behavior, and well-being. The approaches discussed in this chapter are described with this term because, while they meet the needs of the people with diagnosable mental disorders who are our focus, these approaches also are intended to apply more broadly to meet the needs of anyone in crisis.

Crisis Lines

The increased presence of crisis lines both locally and nationally is an important step in minimizing harm to people with mental disorders (SAMHSA, 2023a). Crisis lines or hotlines, other than 911, are precisely what was envisioned at the “Intercept 0” point of diversion discussed in Chapter 4 of this text. Crisis lines provide a connection between a person in need and services—someone to call—while bypassing police and criminal justice system involvement. Two examples of this type of diversion are the new federal Suicide and Crisis Lifeline (988) and, in Oregon and elsewhere, county-based hotlines.

Lifeline: 988

While Congress approved funding for a national suicide prevention hotline more than twenty years ago, the shift to nationwide use of the 988 “Suicide and Crisis Lifeline” did not occur until 2023. The 988 Lifeline was conceived as an easy-to-remember 911 alternative where people could seek help without calling the police (figure 5.7). Now, anyone throughout the country can dial or text 988 at any time to reach a trained counselor and get assistance in managing a crisis for themselves or someone else. People using the 988 Lifeline need not provide any payment or insurance information to receive support.

In the longer term, the vision for 988 is to build a robust crisis response system across the country that links people who call, text, or chat to community-based providers who can deliver a full range of crisis care services (mobile crisis teams or stabilization centers), in addition to connecting people to tools and resources that will help prevent future crisis situations. The 988 number currently accesses a network of over 200 locally operated and funded crisis centers around the country. The federal government is also making significant investments to “scale up” physical crisis centers that would support 988 users in a way that would transform crisis care in the United States. As 988 creators observe, this envisioned transformation relies on the willingness of states to step up with investments of their own to strengthen crisis care at the local level.

One innovative idea being used in some states is the embedding of 988 call centers within 911 facilities. This eases the shift of emergency calls away from fire and law enforcement responses to behavioral health call-takers, resulting in improved responses to community members as well as savings for taxpayers. One Houston, Texas, county implementing this model reported savings of $6.5 million over four years just by diverting calls away from police and fire departments to behavioral health call takers (SAMHSA, 2023a; Neylon, 2021). The call takers in the Houston program are rigorously trained and are required to have a bachelor’s degree in a relevant field, as well as expertise in crisis resolution, cultural awareness, and trauma-informed care, among other topics (SAMHSA, 2023a).

Oregonians have rapidly engaged with the 988 service. Reports from mid-2023 indicate that Oregon residents reached out to 988 about 53,000 times between July of 2022 and July of 2023, representing a 30% increase over calls to the previous national 10-digit suicide hotline. Nearly all of the Oregon calls are routed to a Portland-based non-profit called Lines for Life, which handles the interactions (Terry, 2023). Oregon is following the directive of federal 988 administrators by investing in programs to support local callers—including more than $1.3 billion in state funds allocated to behavioral health programs overall in 2021 (Terry, 2023). For Oregon calls to 988, a very small number (about 3%) result in call takers contacting emergency services, generally non-police supports such as Project Respond or CAHOOTS, both of which are discussed later in this chapter. Some callers request follow-up with a counselor, and some others are referred to services such as food assistance or peer support (Terry, 2023).

Local Crisis Lines

While 988 has been very successful, local call centers also continue to serve people in most states. Where states already operated crisis call centers prior to the 988 rollout, those lines continue to operate using local 10-digit or three-digit numbers, such as 211 (SAMHSA, 2023a).

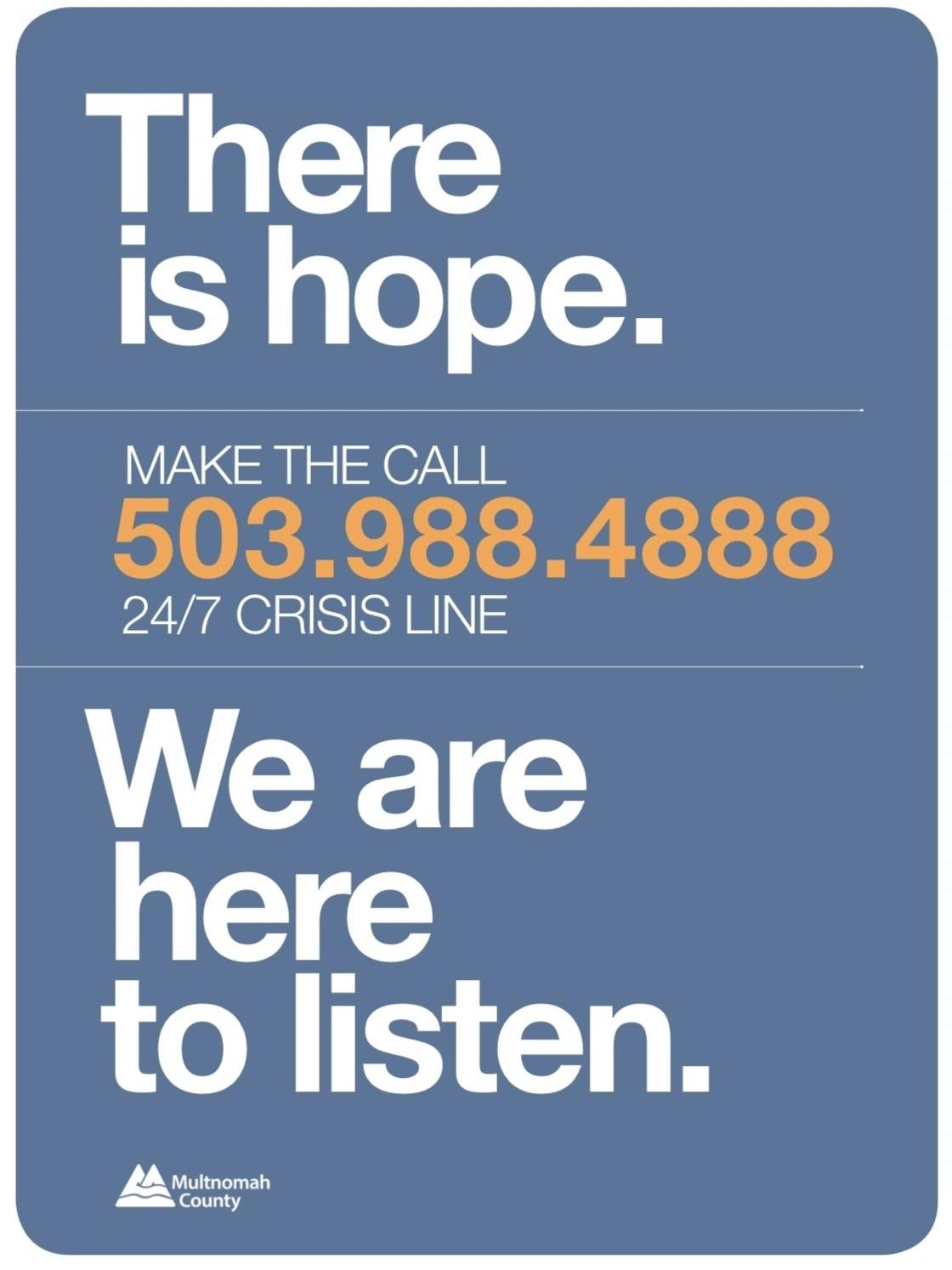

Multnomah County, which includes Portland, as well as other counties in Oregon, have long maintained mental health crisis lines locally (figure 5.8), and they continue to do so, encouraging people in crisis to use these resources as alternatives to 911 (KGW8, 2021).

If you are interested in exploring available mental health resources in your state—including local hotlines—county websites are a good source of information. In Oregon, the largest of those is Multnomah County Behavioral Health [Website]. NAMI also provides listings of crisis and helplines, many of which are targeted to particular marginalized populations based on race, gender, tribal affiliation, or specific needs, such as abuse survivors or veterans. Take a look at NAMI’s Oregon listings if you are interested: Get Help Now – NAMI Oregon [Website].

Mobile Crisis Response Teams

As noted, “someone to call” is only the first step in a crisis response system. The next step is providing people to respond. Preferred responses avoid overuse of law enforcement and seek to avoid unnecessary hospitalizations or other problems, such as impacts on housing. Mobile crisis response teams, or simply mobile crisis teams, have emerged as the preferred “person” to respond to mental health calls, replacing police response where possible.

Mobile crisis teams are teams that respond to behavioral health crises in the community. These teams take different forms, but mental health authorities have outlined best practices that are recommended for mobile crisis teams. Under these guidelines, team members typically include a mental health provider and a peer specialist. Two-person teams are preferred for safety reasons and to most effectively divert people away from hospital emergency departments and the criminal justice system. Emergency medical service (EMS) providers can also partner with crisis teams where needed. Mobile crisis teams, according to best practices, are intended to respond without law enforcement accompaniment unless their presence is necessary (figure 5.9). Ideally, the mobile crisis team can respond to people wherever they are located and at any time of day.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=PtW0qTXd_sY

Mobile crisis teams can offer an array of services: screenings and assessments, de-escalation of crises, and medical and behavioral health follow-up and planning. If a person needs to be relocated to receive mental health or other treatment, the team can support them through the transportation and handoff process. However, nearly 85% of people needing crisis team response receive an intervention other than being taken to the hospital (Wesolowski, 2022).

Mobile crisis teams save money by reducing hospitalization and incarceration of people with mental disorders. Additionally, there is evidence that people are truly helped in the long term. For example, people with mood or psychotic disorders who have disconnected from mental health services are more likely to ultimately re-engage with mental health services after contact with a crisis team (Wesolowski, 2022).

As of 2023, almost every state has functional mobile crisis teams or is in the process of establishing teams. However, these teams are far from universally available, and there continue to be many people who cannot be served by crisis teams. Many states struggle to staff full-time crisis teams or to staff any teams at all in rural or remote areas. Fortunately, Oregon has multiple examples of mobile crisis support services making a difference in our communities.

Project Respond

Project Respond is a mobile mental health crisis team run by long-standing Oregon non-profit Cascadia Health. The two-person team provides 24-hour services to people in Multnomah County, 7 days a week. In addition to gathering information at the scene, assessing risk, and safety planning, Project Respond teams provide follow-up services to help people recover and connect them with peer wellness services (Cascadia Health, n.d.-b). Project Respond emphasizes the agency and voice of people who are in crisis, recognizing that—even in crisis—people need to be consulted on what will help them and to be included in the creation of their own safety plans (Cascadia Health, n.d.-a).

Watch the video linked in figure 5.10 to see a short (4 minute) news clip featuring the director of crisis services at Cascadia Health sharing an overview of Project Respond.

Portland Street Response

Portland Street Response is a newer program that is operated by Portland Fire and Rescue and accessed through 911 calls (figure 5.11). Typical calls include situations where a person is visibly distressed or intoxicated in public or where a person is “down” on the street and needs to be checked. Portland Street Response teams do not respond to private homes, to suicide calls, or to scenes where weapons are involved. As of this writing, teams are available to respond to calls city-wide from 8 a.m. to 10 p.m., 7 days per week, with the hope that hours can be expanded in the future (Portland Street Response, 2023). Portland Street Response is not a mental-health staffed team like Cascadia’s Project Respond, and it has more limits on its ability to respond and act than the Cascadia team does. For example, Portland Street Response workers do not have the authority to perform mental health “holds” when people are a danger to themselves or others (discussed in more detail in Chapter 9 of this text). Some believe this limitation is a barrier to Street Response’s ability to provide proper aid; others believe this limitation is beneficial (Peel, 2023). Nonetheless, Portland Street Response teams provide a police alternative that can meet the needs of many people in our community who are at risk of criminalization or other harm if they come in contact with police. Despite funding challenges and some struggles to find their proper lane in the array of 911 services, many people point to the reduced burden on police and fire departments and the increased availability of help for people on the streets as signs of success and reasons to expand the Portland Street Response program (KGW8, 2022; Zielinski, 2023).

Portland Street Response took some inspiration in its creation and approaches from the very successful police-alternative program CAHOOTS (an acronym for Crisis Assistance Helping Out on the Streets) which has been operating in Eugene, Oregon, for more than 30 years (Zielinski, 2023). See the Spotlight on CAHOOTS in this chapter for more details.

SPOTLIGHT: CAHOOTS

The CAHOOTS program in Eugene, Oregon, run by the non-profit White Bird Clinic, has been quietly succeeding as a police-alternative response team for about thirty-five years (figure 5.12). The White Bird Clinic, and later CAHOOTS, were created by self-described “hippies” in Eugene who were surprised to find themselves partnering with law enforcement but appreciate the unique elements of their program that fit well in its hometown (Parafiniuk-Talesnick, 2021). After George Floyd was killed by police officers in 2020, once again turning public focus to violent police encounters and their potentially horrific outcomes, the CAHOOTS program gained deserved attention and praise among people searching for approaches that could truly help make a difference in avoiding these encounters, particularly when they involve mental health crises (Parafiniuk-Talesnick, 2021).

On its website, CAHOOTS explains that its mobile crisis intervention services are offered 24 hours per day, 7 days per week throughout the Eugene metro area and in the neighboring city of Springfield. CAHOOTS teams, which include a nurse or EMT and crisis worker, are summoned and dispatched through the 911 emergency system or the police non-emergency number. These teams travel to the person in need with the ability to offer crisis counseling and conflict resolution, as well as more concrete support, such as first aid and transportation to services (White Bird Clinic, n.d.). CAHOOTS is funded by the City of Eugene, supplemented by donations.

What doesn’t CAHOOTS do? They do not serve as law enforcement; they do not make arrests. They are unarmed and do not use lights or sirens. However, CAHOOTS is clear that they are in partnership with police and fire departments. They cannot respond to scenes of violence, where weapons are involved, or to “criminal or dangerous situations” (White Bird Clinic, n.d.). In a social media post linked on its website, CAHOOTS poses the question: “How does CAHOOTS both support Black Lives Matter and work with police?” Their answer: “Thoughtfully. . . . Police officers and the fire departments are our community partners in the public safety system. Our work is different, but it overlaps. We work together to respond to community needs” (White Bird Clinic, n.d.).

CAHOOTS reported that in 2020 they responded to around 24,000 calls and requested police backup about 250 times. This is an enormous money-saver, estimated to reduce yearly Eugene public safety expenditures by about $8.5 million, and ambulance and emergency room costs by about $14 million. The entire annual CAHOOTS budget is just over $2 million (White Bird Clinic, n.d.).

The CAHOOTS program attributes its success to several factors, including its longstanding position of trust in the community as well as the primary goal that underlies all of its actions: to help. A key to good outcomes is certainly the robust staff training. Compared to police officers who may have a few dozen hours of training on crisis response, CAHOOTS workers typically undergo several hundred hours of training and practice in crisis response, de-escalation, and other tools—in the classroom and the field—before operating independently in two-person teams. Notably, team members also participate in mentorship programs to process their crisis work and maintain their own mental health so that they can continue to productively serve others (Beck et al., 2020). The importance of these measures is discussed more in Chapter 10 of this text.

If time allows, watch the linked video clip in figure 5.13 to hear from former CAHOOTS crisis worker Ebony Morgan, who was interviewed about the program in 2020 in the aftermath of the George Floyd murder. Morgan shares her personal connection to the mission of the program (her own father was killed in a police encounter), as well as her professional insight on why and how CAHOOTS works so well.

Crisis Stabilization Centers

The third core element in a functional crisis response system is a “place to go.” Although the preference is for services to meet people where they are and serve them without the need for relocation, that is not always possible. Whoever responds to a crisis (including police) may need a place to transport a person to keep them safe. Without appropriate alternatives, that place tends to be either a hospital emergency department or a jail—both expensive and usually inappropriate options for a person experiencing a temporary mental health crisis. While the problems inherent in jailing people are obvious, many people may not realize that the chaotic and stressful environment of hospitals can also be very difficult and disruptive for people in crisis, not infrequently leading to escalating problems.

Places that best serve people in crisis are often known as crisis stabilization centers or receiving centers. Regardless of the precise name, these are facilities that typically focus on less than 24-hour care (i.e., they are temporary and non-residential) for behavioral health crises, and they follow what is called a no-wrong-door approach. The no-wrong-door idea is meant to convey that anyone can receive services there, whether they walk in or are brought by a crisis team or law enforcement, and once there, they will be assessed for whatever care they need at whatever level, large or small. No one is turned away or treated as if they came in a “wrong door.”

Many factors contribute to the creation of a no-wrong-door facility. For example, chairs and recliners, rather than beds, may be offered to ensure that physical space is not a barrier to admission. Stabilization centers must also make the commitment that when a person needs additional treatment, the facility will make that determination and any necessary arrangements. Specifically, law enforcement should never be put in the position of assessing a person’s needs and navigating the crisis system. With the understanding that no one will be rejected and a smooth handoff will be possible, first responders will (in theory) not hesitate to use this option as a “place to go” rather than jails or hospitals.

The majority of states have at least some crisis stabilization programs in place, and many have facilities in the works, if not yet fully operational. However, as with mobile crisis services, assuring these programs are available statewide and 24/7 is a major challenge for nearly all states. Hiring and training a workforce to staff these facilities is the biggest challenge.

Watch the short video linked in figure 5.14 to learn about the Stabilization Center in Deschutes County, which provides many services, including a 23-hour respite center.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=i5RG4zdcb14

Crisis stabilization centers can be supported by facilities that provide slightly different levels or types of service. Examples are short-term residential facilities, which are home-like facilities that can serve as an alternative to hospitalization for people who need more continuous monitoring. Peer-operated respite programs are also short-term care facilities but run by peers. Some facilities offer the valuable services of a stabilization facility but must limit those to certain needs or certain days and hours. In Hillsboro, Oregon, for example, the Hawthorn Walk-In Center is highly praised but only available during part of the day, 6 days per week (Washington County, n.d.). Oregon, like many states, needs far more stabilization and support programs than it has available, and there is not always agreement on where funding should be directed (e.g., longer-term facilities versus “no wrong door” crisis facilities that take all comers) (Bernstein, 2023).

Licenses and Attributions for Reducing Police Encounters: Crisis Response

Open Content, Original

“Reducing Police Encounters: Crisis Response Systems” by Anne Nichol is licensed under CC BY 4.0.

“Crisis Lines” by Anne Nichol is licensed under CC BY 4.0.

“Local Crisis Lines” by Anne Nichol is licensed under CC BY 4.0.

“Project Respond” by Anne Nichol is licensed under CC BY 4.0.

“Portland Street Response” by Kendra Harding, revised and expanded by Anne Nichol, is licensed under CC BY 4.0.

“SPOTLIGHT: CAHOOTS” by Anne Nichol is licensed under CC BY 4.0.

Open Content, Shared Previously

“Lifeline: 988” by Anne Nichol is adapted from 988 Suicide & Crisis Lifeline by SAMHSA. Modifications by Anne Nichol, licensed CC BY 4.0, include condensing content.

“Mobile Crisis Response Teams” by Anne Nichol is adapted from National Guidelines for Behavioral Health Crisis Care and Snapshot of Behavioral Health Crisis Services and Related Technical Assistance Needs Across the U.S., both by SAMHSA. Modifications by Anne Nichol, licensed CC BY 4.0, include revising and condensing content.

“Crisis Stabilization Centers” by Anne Nichol is adapted from National Guidelines for Behavioral Health Crisis Care and Snapshot of Behavioral Health Crisis Services and Related Technical Assistance Needs Across the U.S., both by SAMHSA. Modifications by Anne Nichol, licensed CC BY 4.0, include revising, condensing, and expanding upon the content.

Figure 5.7. “There is Hope. Text or Call 988” by SAMHSA, which is in the Public Domain.

All Rights Reserved Content

Figure 5.6. NAMI crisis response video by NAMI is licensed under the Standard YouTube License.

Figure 5.8. “24/7 Crisis Counseling” by Multnomah County Behavioral Crisis Intervention is included under fair use, permission request pending.

Figure 5.9. Mobile crisis team hits the streets in Clark County by KGW News is licensed under the Standard YouTube License.

Figure 5.10. How Project Respond supports our community with crisis mental health care by KGW8 is licensed under the KGW8 Terms of Service.

Figure 5.11. Photograph of Portland Street Reponse by Portland.gov is all rights reserved and included with permission.

Figure 5.12. Cahoots Van by White Bird Clinic is included under fair use, permission request pending.

Figure 5.13. CAHOOTS Interview on CNN – Alternatives to Police Response by Ebony Caprice Morgan is licensed under the Standard YouTube License.

Figure 5.14. Stabilization Center Tour by Deschutes County is licensed under the Standard YouTube License.