8.2 Gender Socialization in the Workplace

As an agent of socialization, workplaces steer a worker’s behavior and norms. Employers can dictate what you wear or how you speak to a boss or customer. Are there certain professions that you consider masculine or feminine? What images come to mind when you think of a nurse or doctor? What does a construction worker or prostitute typically look like? Later in this chapter, you can follow the link to the ‘gender bias test’ where you can test your own biases for gendered expectations of workers.

Society’s gender expectations influence our perceptions of workplace norms. In this chapter, you will learn about how society’s structures affect job choices. These unwritten ideas for who fits into a particular job can guide our choice of profession. Colleague interactions are another aspect of work covered in this chapter. Workers influence each other’s expected gender norms and behaviors. For instance, if you walk into a meeting room of diverse genders and ages, what are your assumptions about who is a manager, an assistant, or an intern?

Figure 8.2. Diverse people in the workplace bring unique experiences which strengthen outcomes for employers.

8.2.1 Sociological Function of Work

Gendered expectations for work start very early in our lives. Education institutions can unknowingly steer gendered behavior and norms, leading to particular job choices. Historically, admissions policies and societal norms restricted women’s participation in higher education. Due to prejudice and discrimination, women were not allowed to attend higher education institutions for many majors, such as math, science, and medicine. The narrow field of education opportunities meant it was difficult for women to qualify for high-paying professions.

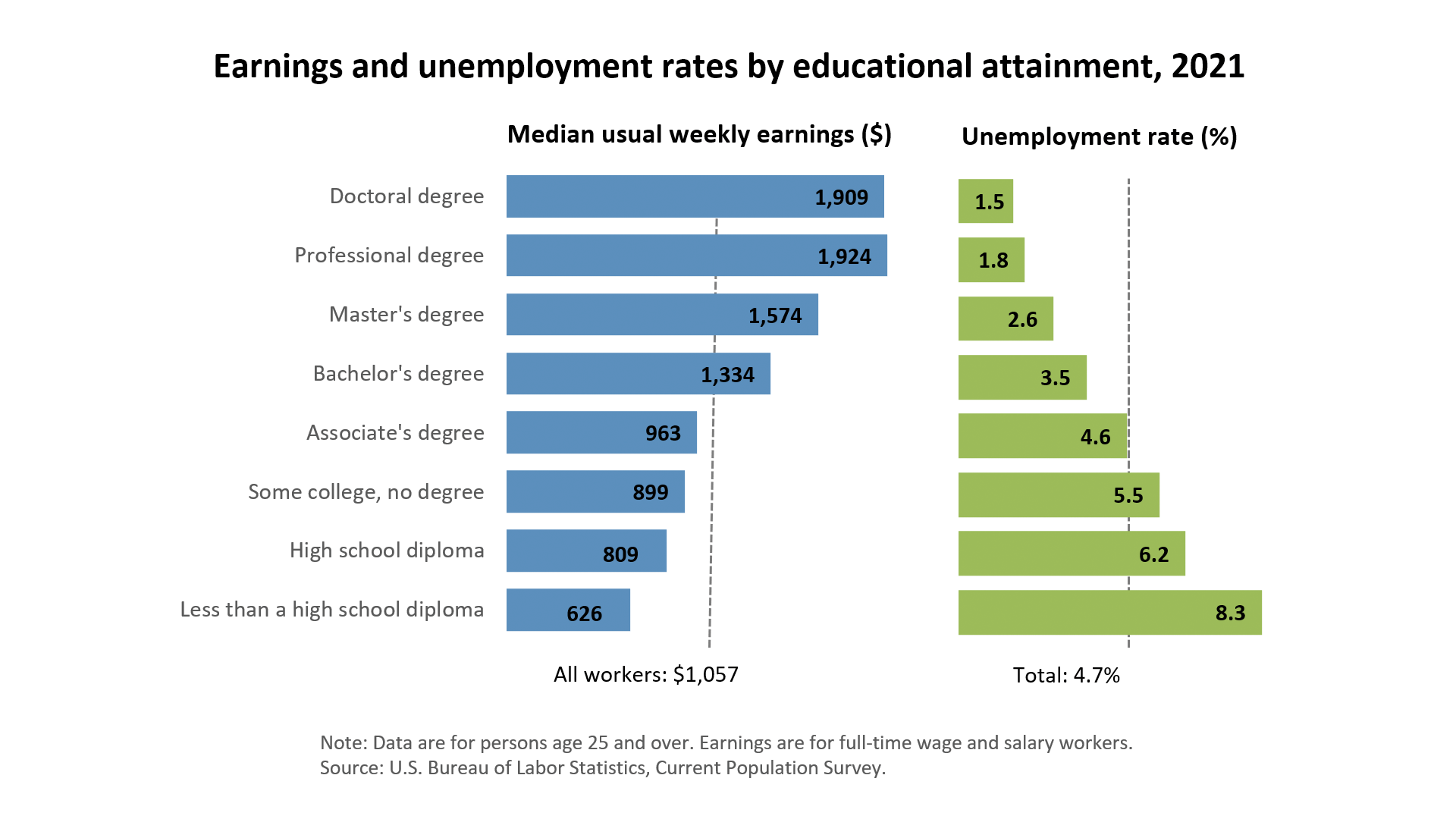

A worker’s level of education directly relates to their likelihood of employment. As we learned in chapter 7, achieving advanced degrees increases a person’s income over their lifetime. Figure 8.3 demonstrates how workers with lower levels of education consistently had higher unemployment rates throughout history.

Figure 8.3. Earnings and unemployment rates by educational attainment, 2021. People with higher formal education are more likely to have higher salaries. They are also more likely to be employed.

Figure 8.3. Earnings and unemployment rates by educational attainment, 2021. People with higher formal education are more likely to have higher salaries. They are also more likely to be employed.

Women have edged out men in achieving bachelor’s degrees in the last few years (National Center for Education Statistics N.d.). Women comprise nearly half of the workforce in 2022. Even though women are on par and even surpassed men’s attainment of bachelor’s degrees, the types of degrees they earn and the jobs they pursue are typically not enough to support themselves or their families. Dual-earning families are often a necessity for struggling working-class families. Middle-class families with dual earners have usually achieved enough economic stability to ensure higher education is accessible to future generations, regardless of gender.

8.2.2 Dual Labor Market

As we think about different types of work, we can use our sociological lens to see how gender stereotypes shape societal expectations. Sociologists use the dual labor market theory to explain how the primary and secondary sectors of the labor market are upheld and based on discrimination, poverty, and power dynamics. Primary sector jobs include high-value jobs such as business, banking, and those needing formal education. Men have traditionally held these jobs. The secondary sector jobs include lower-value jobs that are service-based or short-term, typically held by women or migrant workers. According to economists, a balance of both types of sector jobs in the labor market means there is a balanced system.

Looking at the dual labor market through the lens of gender, we can see that workplace stereotypes are ingrained in our society. Gender stereotypes even exist in the language we use to describe different jobs. For example, entry-level and service industry positions have historically been labeled pink-collar jobs because women traditionally hold them. Pink-collar jobs such as secretary, nurse, and elementary school teacher customarily bring about an image of a female.

On the flip side are the primary sector, or higher-value jobs, traditionally seen as masculine jobs. Historically held by men, blue-collar jobs encompass physical labor such as construction or power-holding jobs such as managers and executives. The term “blue collar” has shifted meaning over the past few decades to include any hourly wage-based working class or manual position.

Transgender workers, labeled purple-collar workers, are employed throughout most industries (Ullah et al. 2021; David 2014). White-collar jobs are those with high societal value and typically take place in an office with heat or air conditioning, involve limited physical labor, and require formal, advanced education.

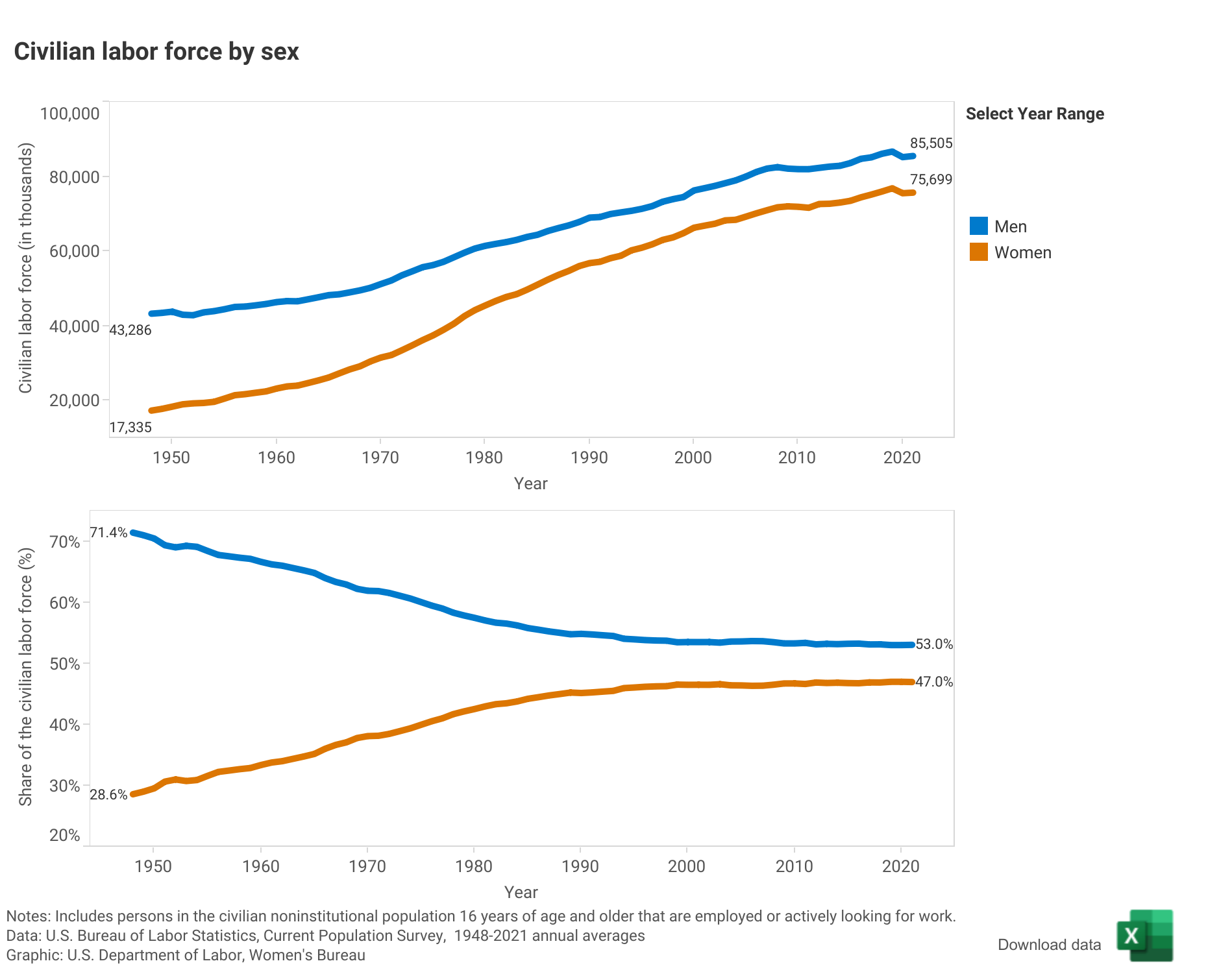

Figure 8.4 shows how many people are in the labor force by gender in the top half of the figure. The bottom half of the figure shows the percent proportion of males and females in the workforce over time. This illustrated the changing face of gender in the workplace. In the next section, we will see how historical factors have led to current gender segregation and gendered norms in the workplace.

Figure 8.4. Civilian Labor Force over time 1948-2021. The top graphic shows how many women and men participated in the workforce over time. The bottom graphic shows the percentage of women and men in the workforce over time. Women’s participation in the workforce has continued to increase in the last 20 years, yet at a slower pace than during the rapid rise of the 1970s-1990s.

8.2.3 Activity: Gender Career Bias

Earlier in the chapter you were asked about what particular workers look like in society. These expectations and stereotypes can guide our ability to obtain and be promoted at work. Supreme Court Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg (1933-2020) is one example of someone who experienced gender normative restrictions in education and the workplace. She was in the top of her class from Cornell University and entered Harvard Law School. Ultimately she graduated from Columbia Law School (tied for first in class overall), yet she was repeatedly denied employment by law firms because she was a woman.

Take the Gender-Career Implicit Association Test to measure your own gender career biases.

8.2.4 Occupational Segregation

The workplace has seen many changes in the last few hundred years. One of the first groups fighting for working women’s rights was the Daughters of Liberty, formed in 1765. (Sweet 2021). In 1873, the Supreme Court ruled that women were prohibited from practicing law. The finding stated, “it was natural and proper for women to be excluded from the legal profession” as women were expected to fulfill “the duties of motherhood and wife.” (Oyez N.d.). Positive progress was made toward gender equality in the workplace with the passage of the Equal Pay Act in 1963. It stated that companies could not pay people differently for the same work based on gender.

More recently, in 2013, the United States military allowed women to serve in previously closed combat designations. 2022 saw the first female aircraft carrier captain in the history of the United States Navy, Captain Amy Bauernschmidt, shown in figure 8.5. When CAPT Bauernschmidt started her career at the United States Naval Academy in the early 1990s, women were prohibited from serving on combat ships (Lendon, Essig, and Josuka 2022). Transgender people have been allowed to openly serve in the United States military as of 2016.

Figure 8.5 Captain Amy Bauernschmidt became the Commanding Officer of the USS Abraham Lincoln in 2022. She is the first female Captain of an aircraft carrier in the U.S. Navy.

Women are currently not restricted by laws specifically preventing them from participating in the labor force. Due to societal norms, women tend to choose lower-paying, which reinforces the gender wage gap. Higher-paying jobs such as pilots, finance, corporate executives, and technical services are male-dominated. Jobs seen as more suited to women’s socially prescribed gendered norms of empathy and caregiving typically pay less. These lower-paying jobs include home healthcare workers, elementary school teachers, and nurses. Gendered societal expectations are taught to us from an early age through agents of socialization, including family, peers, religion, and media.

While gendered norms have become more balanced in most industries in recent decades, stereotypes still exist. There are many benefits to all workers, employees, and companies when people of all genders are included in a diverse range of industries. For the medical industry, having a more balanced representation of employees across all demographics provides a positive workplace for employees and better patient health outcomes (Gomez and Bernet 2019). Addressing equal gender representation in decision-making arenas such as corporate Chief Executive Officers (CEOs) and the Supreme Court may improve workplace equality for all genders.

8.2.5 Biological Fallacies of Role Performance

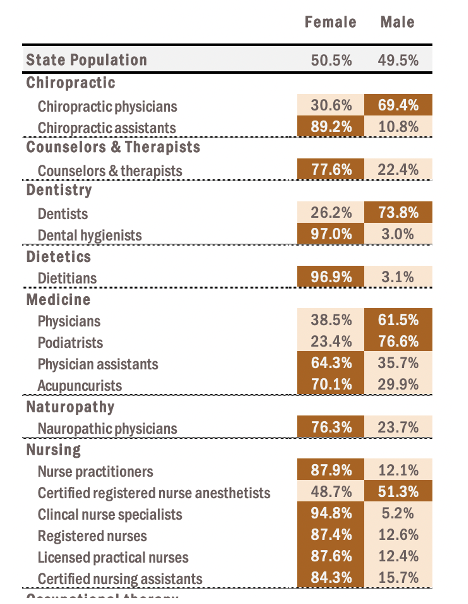

Gendered norms and expectations of physical ability for workers can be found throughout many industries. People who choose a nursing career are thought to be naturally caring and nurturing, so a fitting job for women, while men are considered doctors who exude authority and knowledge. In Oregon in 2017, 61.5% of physicians were male, while 87.4% of registered nurses were female (Oregon Health Authority Office of Health Analytics 2019:2). Figure 8.6 shows the gender representation in Oregon for some medical fields.

| Population | Female | Male |

|---|---|---|

| State Population | 50.5% | 49.5% |

| Chiropractic physicians | 30.6% | 69.4% |

| Chiropractic assistants | 89.2% | 10.8% |

| Counselors and therapists | 77.6% | 22.4% |

| Dentists | 26.2% | 73.8% |

| Dental hygienists | 97% | 3% |

| Dietitians | 96.9% | 3.1% |

| Physicians | 38.5% | 61.5% |

| Podiatrists | 23.4% | 76.6% |

| Physicians Assistants | 64.3% | 35.7% |

| Acupuncturists | 70.1% | 29.9% |

| Naturopathic Physicians | 76.3% | 23.7% |

| Nurse practitioners | 87.9% | 12.1% |

| Certified registered nurse anesthetists | 48.7% | 51.3% |

| Clinical nurse specialists | 94.8% | 5.2% |

| Registered nurses | 87.4% | 12.6% |

| Licensed practical nurses | 87.6% | 12.4% |

| Certified nursing assistants | 84.3% | 15.7% |

Figure 8.6. Gender Representation in Oregon for select medical fields, 2019. Women are more likely to be employed in medical fields which require less education and earn less pay such as physician assistants and dental hygienists compared to dentists and physicians.

When people act in a way considered feminine or masculine by society, this is called doing gender. See Chapter 2 for more about “doing gender.” These notions of gendered norms and expectations for behavior are based on beliefs that some genders are biologically better equipped to handle some specific types of jobs. For instance, women are considered incapable of working in jobs requiring physical strength. Women account for only 10% of the construction workplace where physical strength is a focus, yet women make up over 46% of the workforce in 2022. Of that 10%, about two-thirds are in clerical or administrative positions (BigRentz Inc. 2022). Although women have proven themselves as physically capable as men across many industries, societal gender stereotypes, and ideas of doing gender still guide people’s choices of profession and hinder their ability to succeed in some industries.

8.2.6 Licenses and Attributions for Gender Socialization in the Workplace

Figure 8.2. Photo by Christina@wocintechchat.com is licensed under the Unsplash License.

Figure 8.3. Earnings and unemployment rates by educational attainment, 2021 by the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics is in the Public domain.

Figure 8.4. Chart by U.S. Department of Labor is in the Public domain.

Figure 8.5 Captain Amy Bauernschmidt by the Naval Air Force, U.S. Pacific Fleet is in the Public domain.

Figure 8.6. Chart based on data from Table 1 in The Diversity of Oregon Office of Health Licensed Health Care Workforce by Oregon Health Authority’s Office of Health Analytics.

“Gender Socialization in the Workplace” by Jane Forbes is licensed under CC BY 4.0.