10.2 Gender and Media Analysis

In this text we have learned that people are born with primary sex traits, including chromosomes, hormones and reproductive organs These traits influence the development of secondary sex traits as we mature, like the size and shape of breasts, the distribution of body hair, and reproductive capacity. Primary and secondary sex-traits have always been subject to various technological modifications, and in recent years technology is evolving to include influencing the development of secondary sex-traits and surgical sexual reassignment. Gender identity and expression are not fixed at birth, and are not necessarily determined by the sex traits we are born with. We have also seen that neither the sex traits we are born with nor the gender identity and expression we grow into fit neatly into discrete binary categories.

We have also learned that gender is socially constructed. Socialization is how we learn the rules, norms, taboos, customs and rituals of our culture. We know that these rules, values, norms, taboos, customs and rituals are socially constructed because of the great variation we observe between cultures and within cultures over time. Socialization creates and maintains social order by attaching meaning and power to specific biological processes and cultural elements.

Gender socialization is the social learning about how meaning and power attaches to sex traits, gender identity and gender expression. All cultures attach power and meaning to sex and gender, and we know that gender is socially constructed because gender norms, taboos, customs and rituals can vary between cultures. Gender socialization can affix or detach biological sex traits to gender identity, dictate normative gender expression, and discipline those who stray outside normative binary conceptions of sex and gender. Theories of intersectionality help us understand that gender is co-constructed with race and class.

Popular culture represents shared cultural elements, like religion, visual art, fashion, music, drama, literature, and popular media that are held in common by people in stratified societies. Popular culture is where a society’s shared ideas about meaning and power can be challenged, negotiated and reinforced. Culture war is a term coined in the late 20th century to define the struggle for cultural change within popular culture. This idea of a culture war attempts to draw clear political lines between those who benefit from, and are invested in maintaining current structures of power and meaning that attach to gender, race and class, and those for whom those structures do not work and who struggle to change them. This political line is also socially constructed, and as such is arbitrary. No matter what “side” of a so-called culture war a person is positioned, we all experience complex and contested gender socialization within popular culture.

10.2.1 Popular Culture and Cultural Change

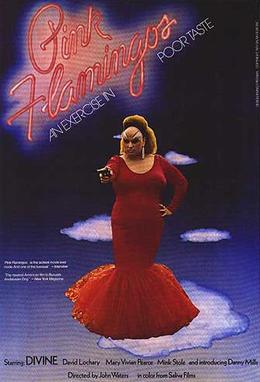

Figure 10.2. The John Waters film Pink Flamingos made the drag performer Divine a subversive gay icon.

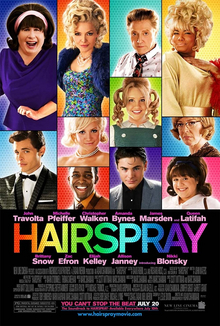

In the opening scene of Hairspray, Tracy buoyantly dances her way through her Baltimore neighborhood and introduces us to her neighbors, including an unnamed “flasher who lives next door”. Viewers in the know recognize the tall slender man in a trenchcoat who gleefully exposes himself to passersby as John Waters, who wrote and directed the grittier original 1988 film of the same name, and who is listed as a co-producer on this frothy remake.

Waters, who identifies as a gay, cisgender man, made 16 films between 1964 and 2004. His famously transgressive “Trash Trilogy”, Pink Flamingos (1972), Female Trouble (1974), and Desperate Living (1977), became cult classics for their x-rated self-described “filth”. They also made the subversive drag performer Divine a camp icon. Waters’ later mainstream films included Hairspray (1988), which was Devine’s last film, Cry Baby (1990) which starred Johnny Depp, and Serial Mom (1994) with Cathleen Turner (IMDb 2023).

Waters is credited with bringing a joyously queer, provocative, campy sensibility into mainstream popular culture. His work asks an audience to look with fresh eyes at forbidden and transgressive elements of everyday life. The essayist Susan Sontag described camp as being more concerned with style than beauty, and characterized by artifice and exaggeration (1964). Camp celebrates glamor and fashion in ways that both mock and transcend dominant gender norms. In the mid-twentieth century camp was recognized as a sort of secret gay code, which Waters effectively deployed in his films. This unapologetic campiness was a key to Waters’ success. Young LGBTQIA people recognized the references, and responded enthusiastically to the validation of their aesthetic sensibilities.

Hairspray is a reworked Cinderella story, in which Tracy goes to a dance, charms a handsome prince and transcends the limitations of her working class origins. While the camp aesthetics of Waters’ films delighted gay audiences, his later films told stories that were accessible to straight audiences. For straight audiences, the camp becomes an added element of fun and camp aesthetics become more accessible and less threatening.

Transgressive art in the context of popular culture can create new configurations of meaning, power and gender. Cultural change can happen when transgressive art moves from the margins of popular culture to the mainstream, as Waters’ work has done.

10.2.2 Analyzing media

In order to analyze media we have to think about four elements: history, text (including narrative, genre, discourse and content), production and audiences (Gillespie and Toynbee, 2006). The process of analyzing art, literature or popular media can help us understand how meaning and power are created, negotiated, contested and reinforced in popular culture.

In order to analyze Waters’ influence in popular culture, we considered the historical context of his films, especially around the changing politics of gender in the late 20th and early 21rst centuries. Waters twisted a classic Cinderella narrative in Hairspray in a way that was accessible and pleasing to a large audience. Waters also used coded campy production elements, like big 60’s hair and drag (men in women’s clothing) to speak specifically to gay audiences.

The exaggerated bouffant hairstyles referenced in the title of the film, were popular in the 1960’s when the film is set. When the original film was made in the ‘80’s fashion had once again shifted to big hair, requiring lots of hairspray. However, instead of signifying hyper-femininity, 80’s big hair was androgynous (figure 10.3). Furthermore, fashionable hairstyles in the 60’s were smooth, in keeping with an idealized aesthetic associated with white women’s hair. By the 80’s the fashion had shifted to favor curls that referenced the natural texture associated with black women’s hair. By using 60’s big hair as a camp element, Waters revealed connections between changing fashions and changing norms about both race and gender.

|

|

|

Figure 10.3a and 10.3b. Instead of signifying hyper-femininity, 80’s big hair was androgynous.

10.2.3 Licenses and Attributions for Gender and Media Analysis

“Gender and Media Analysis” by Nora Karena is licensed under CC BY 4.0.

Figure 10.2. Theatrical release poster for Pink Flamingos. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Pink_Flamingos_(1972).jpg#/media/File:Pink_Flamingos_(1972).jpg

Figure 10.3a. Theatrical Release Poster for Hairspray. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Hairspray2007poster.JPG

Figure 10.3b. “The Star Sisters” Image by Robert Hoetink, CC BY-SA 4.0. https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/9/99/Vlnr_ingrid_ferdinandusse_patricia_paay_yvonne_keeley-1642442755.jpg