2.2 Construction and Imposition of Gender

Sex and gender are two different concepts. In the United States, however, these terms tend to be used interchangeably. Biological sex is typically assigned at birth based on biological and anatomical characteristics. In contrast, gender, as we explained earlier, is a social identity ascribed to individuals, typically based on their biological sex, which dictates socially appropriate status, roles, and norms for behavior.

You can think of sex as the biological differences at birth, such as chromosomes (XY, XX), gonads (testes, ovaries), hormones (androgen, testosterone, estrogen, progesterone), genitals (penis, vagina), and secondary sex characteristics (body hair like pubic or facial, breasts). You can think of gender as the social components one is taught and enacts in everyday life, such as clothing, body modification and ornamentation, norms, values, beliefs, behavior, abilities, roles, and status in society. Sociologists describe this array of social tendencies as the social construction of gender.

A social construct is an idea created and accepted by people within a society and certain cultures. It has no inherent meaning or definition on its own, only what society ascribes, but it has real-life consequences for many people and groups. Sociologists use the term bias to examine how these constructs affect us. Bias is an individual’s tendency (either known or unknown) to prefer one thing over another that prevents objectivity and that influences understanding or outcomes in some way.

Gender bias occurs when someone privileges the words and experiences of a particular gender over others. In professional writing, for example, gender bias often appears in the use of pronouns, such as using “he” as to refer to everyone as opposed to a gender-neutral option like “they”. Other common examples of gender bias include citing primarily male sources to the exclusion of females, nonbinary, or gender-fluid individuals or using different standards for praising men and women.

2.2.1 Gender Identity and Expression

Gender also falls into the category of identity. Gender identity is your connection to your gender, which may or may not match your birth sex or fall into the socially established masculine or feminine binary. When we look at everything that makes up gender, we realize that gender expression, the way one expresses gender identity through clothing, appearance, and behavior, has more than two sides. Think of gender as a spectrum with variations of every color. None of the colors are identical. The spectrum in figure 2.2 represents gender as a concept, not only as an expression.

Figure 2.2. As this chapter explains, gender falls on a spectrum of many and all variations in contradiction to a social norm of simple male/female or masculine/feminine. Gender looks more like the image on the left than what is usually socially taught on the right.

For example, maybe one day you wear a dress and makeup, and the next you wear baggy sweats and a beanie. Society may interpret your gender expression differently based on what you’re wearing. Maybe you don’t feel different, or perhaps you do? One day you might “enact” more traditional feminine aspects of society. The next day you may exhibit more traditionally masculine aspects of society. This chapter will explore how gender is a performance in which we choose the parts and pieces we play every day.

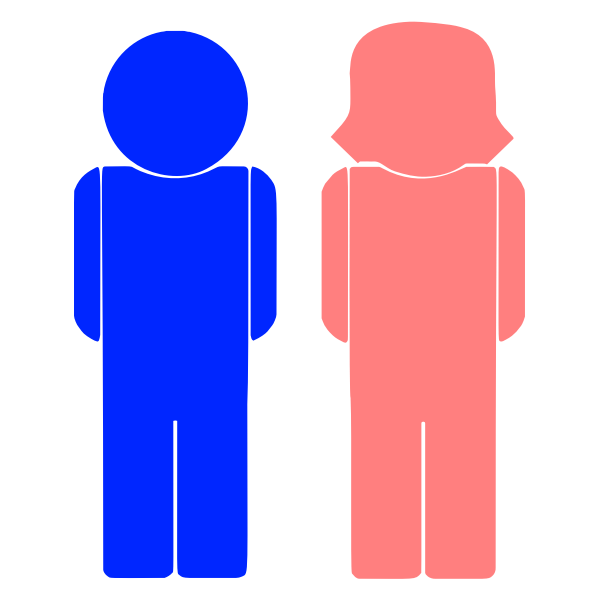

Sexual identity or sexual orientation is a social identity ascribed or chosen by individuals based on their gender and the gender of the object of sexual desire. Sexuality includes personal and interpersonal expression of sexual desire, behavior, and identity. Figure 2.2 shows a “genderbread person” that can help us visualize these terms and concepts. Look at it to get a clear picture of what we are framing this text around. Notice how gender identity, expression, biological sex, and sexual and romantic attraction exist on a continuum and contribute to the idea of one’s sexual identity.

Figure 2.3. The Genderbread person shows a person and points out the different aspects that we have just discussed. Gender identity is mental/emotional, attraction is in the heart as sexual or romantic attraction, biological sex is maleness/femaleness from birth, and expression is outward enactment of all of those pieces in one’s own way. For further context and information on this image and content visit The Genderbread Person.

2.2.2 Sex Assigned at Birth and Gender Reveals

Biological sex is medically assigned at birth and based on visible genitalia, anatomical, or physiological markers. Once a child is labeled biologically male or female, they are generally raised as a girl or boy. Socially, we tend to equate biological sex with gender through multiple visual and social cues such as names, clothing, hairstyle or decorations, color scheme (blue/pink as seen in figure 2.4), or other gender markers (Lorber, 2009). This deeply ingrained way of thinking results in the social acceptance of people who are cisgender, or those whose biological sex aligns with their gender identity, to the exclusion of those who don’t fit neatly into this category.

Figure 2.4. This composite image shows two babies, one in a pink frilly swimsuit and one in a blue dress shirt with suspenders, illustrating how our society assigns gender from birth with markers like clothing.

A recent trend that involves the imposition of gender is the gender reveal party. These social events involve parents or families planning an activity where they disclose the biological sex of an unborn child, thus socially assigning a gender to the unborn child. Some may pop a balloon and either pink or blue confetti falls out, cut a cake that has pink or blue inside, or shoot off colored pink or blue fireworks. You might have seen a gender reveal on social media. Some gender reveals even make the news when something goes awry. One particularly unfortunate gender reveal included fireworks that started a massive fire.

The gender reveal is a relatively new concept, although baby shower announcements with phrases like “it’s a boy!” have existed since the 1950s. The gender reveal phenomenon began in 2008 with a blog post by Jenna Karvunidis. She had a custom-made cake that, when cut, revealed her baby’s sex. She describes the events that came after this party of such a strong focus on the sex of the baby, and the increase of gender reveal parties after her event, as extremely unfortunate. She regrets that her one action of a big gender reveal began a massive trend of focus on just one aspect of a human, their gender. In a recent post on social media, Karvunidis reveals that the baby whose sex she announced via a sliced cake is now a girl who wears suits who goes “outside gender norms” (NPR, 2019)

Judith Lorber, a founding theorist of the social construction of gender, developed and taught some of the first courses on the sociology of gender. Her theory states that gender is:

- a process that creates the social differences that define woman and man;

- a system of stratification that ranks men above women; and

- a structure or social institution that is one of the major ways in which individuals organize social life.

She explains, “Once a child’s gender is evident, others treat those in one gender differently from those in the other, and the children respond to the different treatment by feeling different and behaving differently. As soon as they can talk, they start to refer to themselves as members of their gender” (Lorber, 2009).

Think back to the first time you thought about your gender or noticed it. You can connect that here to the first time you told someone you were a boy or girl or referenced your “sister” or “brother.” We start referring to our gender based on our biological birth sex. But gender is a process society creates and continues to apply to us as we enact it.

2.2.3 Transgender and Cisgender Identities

This standard assignment of sex at birth led to the creation of the term transgender—trans as an abbreviation—which means that one’s sex assigned at birth does not align with one’s gender identity. This term dates back to the 1970s, but the term cisgender, meaning that one’s internal connection to gender matches their sex assigned at birth, came much later in the mid-1990s (Merriam-Webster, 2022). Most people identify as cisgender, but there are many that identify as transgendered in America 1.6 million, .5% of those 18 and older, and 1.4% of the youth population aged 13-17 (Williams Institute, 2022).

Typically, trans men were assigned female at birth, and trans women were assigned male at birth, but their gender identity does not coincide with those assignments. Trans individuals may or may not seek medical treatment to change their secondary sex characteristics or their biological sex. Hormone treatments are one example of medical interventions that allow individuals to develop secondary sex characteristics such as facial hair or increase breast formation. There are also surgical options such as top surgery (the removal or addition of breasts), hysterectomies or removal of female sex organs, or change of external sex organs (addition of penis or vagina).

For trans individuals, their gender expression is typically either feminine or masculine. This helps to express their identity clearly, but there are many variations of expression along the gender spectrum that are not binary. Some trans people identify as neither female nor male. For instance, transmasculine nonbinary individuals were born female, but their gender expression is more masculine, and they identify as nonbinary.

Many issues facing the trans community link back to the social construction of gender and the binary boxes for biological sex required by society and those in power. Trans and nonbinary people who do not fit into those boxes can experience harmful effects in many places in our world. Check out the video in figure 2.5 for a glimpse into the lived experience of a Black trans person confronting issues of safety, visibility, and acceptance.

Figure 2.5. This video was published by a Black trans man and is a poetic commentary about his lived experience as a trans person. It discusses the struggles and experiences that he has gone through in our society and how he has to fight to validate and define his identity as transgender.

2.2.4 Myths about Sex and Gender

The myths surrounding sex and gender have real consequences. Some common and harmful myths surrounding sex and gender include the following:

- Sex is a single trait.

- Sex is binary.

- Genitals equate to gender.

- Gender is a choice.

The first myth is that sex is a single trait, but as we’ve discussed, there are many variations of biological sex. A person may have different components of those traits, including chromosomal variations or biological variations, such as a penis and ovaries. The more scientists and medical staff learn, the more evidence shows that biological sex is a spectrum similar to gender.

The second myth is that sex is binary. If there are variations in biological sex, they cannot be simply female or male. A binary understanding of sex disregards and invalidates those who fall outside that oversimplified binary.

The third myth is that genitals equate to gender. While genitals are a biological sex component, gender is a social construct. Reinforcing the idea that a penis makes one male and a vagina makes one female is harmful. We can see this damage in current events involving sports and schools. Laws in Ohio and New Jersey allow school staff and sports coaches to “check for genitals” on their students/players to decide if they can participate in gendered sports and on which team. For example, whether someone can participate in “girls basketball” (figure 2.6) can be based on a genital check that affirms they have a vagina, if they do not they would not be able to participate in the sport (New Jersey Legislation, 2022; Ohio Legislation, 2022). This is dangerous and harmful for many reasons, including the invasion of privacy and the potential for sexual assault.

Figure 2.6. A women’s basketball team, new laws in Ohio and New Jersey have made it so that a person’s genitalia can be checked to decide if they can play or participate in gendered sports.

The fourth and final myth is that gender is a psychological choice. This myth suggests that someone wakes up one day and decides to change their gender. This myth is a common theme we see throughout anti-LGBTQIA+ discussions, laws, policies, and within communities throughout the U.S. Think of this by flipping it on its head: when did you decide you aligned with your biological sex? If you have never thought about whether your gender aligns with your biological sex, that’s a privilege. Those who are gender nonconforming, or do not fit into the binary gender norms, have had to allocate energy, time, emotions, and so much thought to how to fit into the world safely.

Trans, nonbinary, and gender nonconforming individuals face major barriers to acceptance, healthcare, support, and other services, as well as experiencing high rates of discrimination, transphobia, hate crimes, bullying, and outcasting from family, friends, and society. According to psychologists and medical professionals across specializations, gender is not a decision or choice one makes. Being trans, nonbinary, or gender nonconforming is also not a disorder that needs fixing (such as attempts at conversion therapy, etc.) (Rodriguez, 2018). The term gender dysphoria refers to intense feelings and struggles and disconnection from one’s biological sex, body, and gender identity. Still, in many cases, this term seeks to medically validate the need for support and assistance. (Sethi, 2021)

Theorists have argued that biological sex is socially constructed, just like gender. They point to the different definitions of sex throughout history, both socially, legally, and medically. In the next section, we’ll take a closer look at the ways that gender has been medicalized and marginalized in the United States.

2.2.5 Licenses and Attributions for Construction and Imposition of Gender

“Construction and Imposition of Gender” by Heidi Esbensen is licensed under CC BY 4.0.

Figure 2.2.a. “Rainbow Spectrum” by PublicDomainPictures.net is licensed under CC0.

Figure 2.2b. “Male and Female Icons” by Free*SVG are in the Public Domain.

Figure 2.3. “Genderbread Person 4.0” by Sam Killerman is uncopyrighted.

Figure 2.4a. “Baby girl in swimsuit blue eyes with sunglasses” by Tammy Anthony Baker is licensed under CC BY 2.0.

Figure 2.4b. “Ikibobok 7 moth Rwandan baby boy” by Lizadeborah03 is licensed under CC BY-SA 4.0.

Figure 2.5. “Invisible: Trans Assimilation” by Hey Xay is licensed under the Standard YouTube License.