2.4 Biology of Sex and Gender

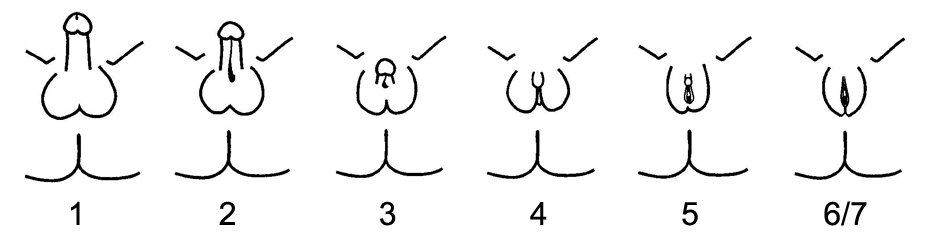

In the U.S. and many Western countries, we assume that sex refers to biological differences between men and women. We assume women have two XX chromosomes, have a uterus, ovaries, and vagina, and more estrogen in their bodies. Conversely, men have XY chromosomes, penises and testicles, and more androgens (like testosterone) in their bodies than women. However, biology is a lot messier. Biological sex is actually a spectrum with our idealized versions of male and female bodies existing at two different ends. Below is an image (figure 2.11) called the “Quigley Scale” developed by pediatric endocrinologist Charmian Quigley in 1995 to show the range of normal infant genitalia from “fully masculinized’’ (1) to “fully feminized” (6/7).

Figure 2.11 Quigley scale of range of infant genitalia descriptors of masculinized to feminized.

2.4.1 Genes and Chromosomes

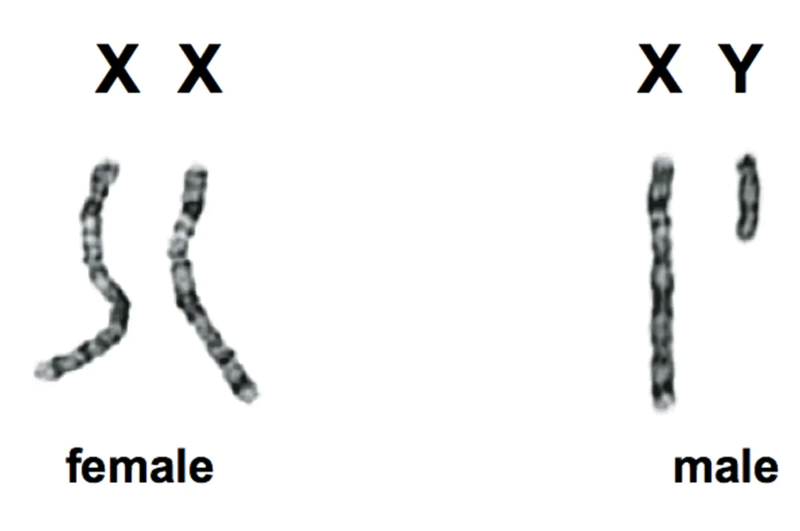

Genes and chromosomes are part of how sex is assigned at birth. Most females at birth have two X chromosomes and males have XY chromosomes and these combinations are inherited from the father. At conception, either an X or Y chromosome combines with the mother’s X chromosome, meaning that female is the default sex because a Y chromosome has to change the XX to an XY (see figure 2.12).

Figure 2.12: Female and Male chromosomes consist of X and Y chromosomes, or sex chromosomes because biological sex is determined by which pair one has.

2.4.2 Hormones

Hormones provide another way to look at the biology of sex. Females typically have higher estrogen and progesterone levels, whereas males have higher testosterone levels. However, many variations have been found across medical research. Estrogen and progesterone support the development of female sex organs and physical traits during puberty, such as breast and uterus development, as well as fertility. Testosterone works similarly in men, assisting in the development of the penis and testes, regulating sex drive, bone mass, muscle development and strength, and production of sperm.

All sexes have varying levels of each of these hormones. Some studies show that testosterone affects social behavior. For example, males who exhibit aggressive or dominant behavior due to testosterone are linked to higher testosterone levels and support higher social status, coincidentally also non-aggressive behaviors that could elevate their social status can be linked back to higer testosterone levels (Dreher, 2016). For females, estrogen and progesterone levels can affect mood, emotions, brain function (such as focus and processing), and connection during and after childbirth to offspring.

When we look at hormone blockers or hormone therapy in trans and nonbinary individuals, the treatment can assist in preventing or assisting in the development of secondary sex characteristics (facial hair, breasts, muscle tone, hips, etc.). Many studies show that these therapies have positive effects on transitioning individuals both physically and psychologically. These treatments shift the balance of the hormones for trans individuals, increasing testosterone in trans men or increasing estrogen and progesterone in trans women to support their gender identity. We will explore this more later, but it is important to note how it fits in here with the biological aspects of sex that lead to gender assignment and changes.

2.4.3 Sexually Dimorphic Traits

Sexually dimorphic traits are the characteristics we associate with each biological sex. Sometimes, an individual can appear female, express themselves as female, use feminine pronouns, but also have masculine traits such as beard growth. The history of the “bearded lady” comes from those with hirsutism, a dimorphic condition where women grow excessive body hair. This condition gained popular attention in early 19th century “freak shows” and circuses, making this either seem like a curse or a path to fame and money. Some of these women were also broad in the shoulders and much taller than other women of the time.

What other things constitute sexually dimorphic traits? Here is a short list of differences in characteristics between males and females assigned at birth:

- Weight

- Muscle mass

- Facial and body hair

- Stature

- Disease prevalence

- Cognitive development

- Genital and breast developments

As we can see through biological research, sexually dimorphic traits are more common than we think and in ways that we may not even recognize. Body mass differs between males and females, as females process food into fat while males turn it into muscle. Males tend to be taller but tall women do exist, which could be considered a sexually dimorphic trait. We’ll discuss more later how this relates to gender in our society.

2.4.4 Activity: Medical Thoughts

“As a clinical geneticist, Paul James is accustomed to discussing some of the most delicate issues with his patients. But in early 2010, he found himself having a particularly awkward conversation about sex.

A 46-year-old pregnant woman had visited his clinic at the Royal Melbourne Hospital in Australia to hear the results of an amniocentesis test to screen her baby’s chromosomes for abnormalities. The baby was fine — but follow-up tests had revealed something astonishing about the mother. Her body was built of cells from two individuals, probably from twin embryos that had merged in her own mother’s womb. And there was more. One set of cells carried two X chromosomes, the complement that typically makes a person female; the other had an X and a Y. Halfway through her fifth decade and pregnant with her third child, the woman learned for the first time that a large part of her body was chromosomally male1. “That’s kind of science-fiction material for someone who just came in for an amniocentesis,” says James.” (Ainsworth, 2015)

- How does this story support the ideas that gender is a social construct that we repeatedly reinforce?

- What would society tell this individual about “who” they are and why?

- Bodies differ in many ways and we associate traits and roles based on what we “see” someone is (masculine or feminine/male or female). Does this story support how we define these assigned roles and behaviors as socially constructed?

2.4.5 Licenses and Attributions for Biology of Sex and Gender

“Biology of Sex and Gender” by Heidi Esbensen is licensed under CC BY 4.0.

“Biology of Sex and Gender?” is adapted from “Identities and Power: Sex, Gender, and Race” by Taylor Livingston in An Introduction to Anthropology: the Biological and Cultural Evolution of Humans, which is licensed under CC BY-NC 4.0.

Figure 2.11. “Quigley scale for androgen insensitivity syndrome” by Jonathan.Marcus is licensed under CC BY-SA 3.0.

Figure 2.12. “XY chromosomes” by AmandaCXZ is licensed under CC BY-SA 4.0.