3.4 Embodied Gender

Bodies may be our friends or enemies, a source of pain or pleasure, a place of liberation or domination, but they are also the material with which we experience and create gender. During the past decades, feminist sociologists and anthropologists have increasingly explored the relationship between bodies, culture, and subjectivity (Dellinger and Williams 1997; Gagné and McGaughey 2002; Lorber and Martin 1998; McCaughey 1998). Scholars appear to be coming to terms with the embodiment of gender, which refers not only to how people use or mold the body to signify gender but also how such bodywork is intertwined with subjectivity (i.e., cognition and feelings).

Embodiment can also be defined as how the cultural ideals of gender create expectations for and influence the form of our bodies. There is a bidirectional relationship between biology and culture. By embodying societally determined gender roles, we reinforce cultural ideals and simultaneously shape our bodies, perpetuating the cultural ideal (Connel, 2002). While there is more variation in body type within the male and female sexes than between the two sexes, embodiment exaggerates the perceived bodily differences between gender categories (Kimmel, 2011).

Social embodiment, for both men and women, is variable across cultures and over time. Examples of women embodying gender norms across cultures include foot binding practices in Chinese culture, neck rings in African and Asian cultures, and corsets in Western cultures. Another interesting phenomenon has been the practice of wearing high heels, which shifted from a masculine fashion to a feminine fashion over time (Figure 3.6 shows some of these examples).

Figure 3.6. These pictures show an old advertisement for a corset, which slimmed waist size, shoe from foot binding, and high heels.

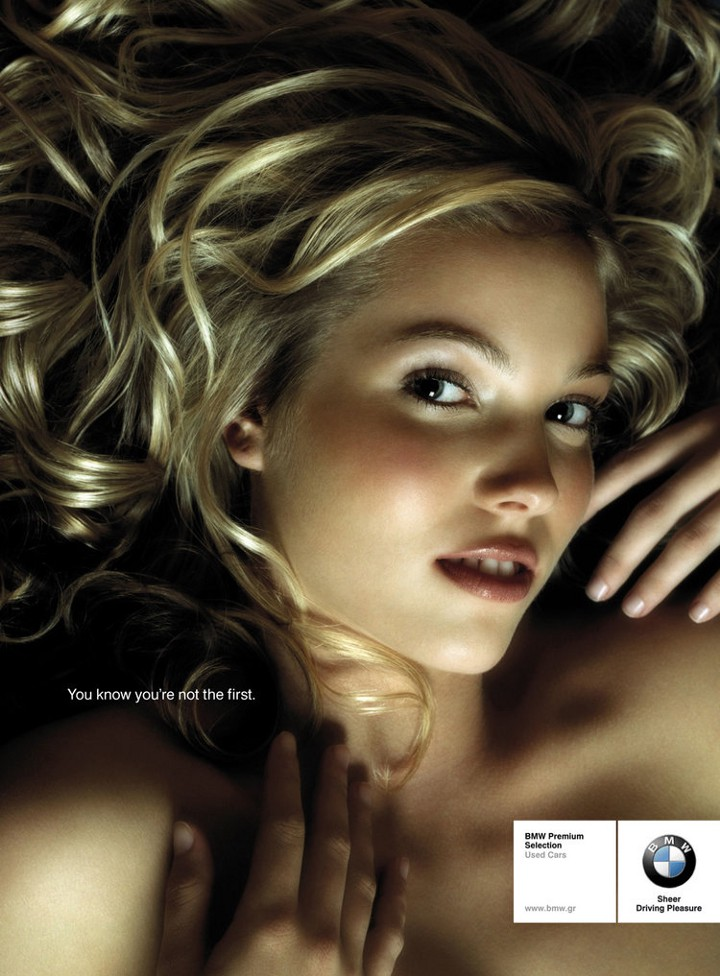

In the United States, the ideal body image and dimensions have changed for both women and men, with the ideal female body shape becoming progressively slimmer and the body ideal for men becoming progressively larger (Bordo, 1999). These differences are epitomized in children’s toys; G.I. Joe dolls depict the physical ideals for boys and Barbie dolls embody the ideals for girls. Beauty myth, as discussed in Naomi Wolf’s book The Beauty Myth: How Images of Beauty are Used Against Women, refers to the unattainable standard of beauty for women, which sustains consumer culture. In contrast, men’s bodies are also “dictated” by cultural ideals of gender, as is evident in consumer culture—especially beer commercials—in which men are portrayed as outdoorsy, tough, strong, and manly (Buysse, 2004).

Every society has different sexual scripts for male and female members to follow. Thus members learn to carry out their feminine or masculine role, much like every society has its own language. From infancy to old age, we learn about and practice the particular ways of being masculine and feminine that our family and society uphold. However, these roles can change over time, place, region, class, caste, and geographical location.

Damaging norms exist for women and men around body and beauty, but as we often see in sociological research, women take the brunt of idealization based on power dynamics. Naomi Wolf describes this in “The Beauty Myth,” that as women gained power, a violent backlash then weaponized female bodies and beauty as political tools. Women were criticized and measured by their looks before all, eating disorders increased, plastic surgery increased, and beauty became more of a currency system. During Hillary Clinton’s run for presidential office, the media judged everything she wore and how she looked with little discussion or critique of male presidential candidates’ physical features or attire.

3.4.1 Idealized Body Type and Size

Our bodies are merely physical vessels that carry us through this life, yet society places labels upon our flesh that politicize, marginalize, and dehumanize us. The stretch marks, scars, cellulite, acne, muscles, fat, curves, and birthmarks are devoid of meaning except for what we ascribe to them. Fitness magazines, airbrushed images of celebrities, CGI movies and music videos are sold to us as reality, which causes a warped perception of actual human bodies. If beauty is in the eye of the beholder, how can we hold ourselves more closely with compassion and see ourselves clearly?

Social norms and gender regulation in our society also connect to idealized body types, sizes, and images. Think of what you’ve seen growing up in media, movies, and advertisements, and you will probably see a clear trend of what “we should look like” as humans. These are based on gendered ideals as well. When someone identifies as a woman, they are expected to look like “a woman.” In figure 3.7, you will see thinness, whiteness, and idealized feminine shapes. The norms are clear even within two images, including a nonbinary individual and a transwoman.

Figure 3.7. images of expressing gender norms around femininity on the top two photos, and femininity expression on a transgender woman and non-binary person. All express the norms of beauty for expressions of femininity.

3.4.2 Fitness and Gym Culture

Sports spaces and facilities like gyms, indoor and outdoor sports halls, and swimming pools are usually organized in a way that presumes the facility users are either women or men. The clearest example is gender-segregated changing rooms, where people must change clothing and shower in either women’s or men’s changing rooms, with minimal privacy. Often, toilets are located inside these changing rooms, meaning people must enter a gender-segregated changing area to use the toilet. When toilets are separate from changing rooms, these are usually labeled female or male or specifically intended for disabled users. Sports spaces are also often organized in a way that presumes that women and men engage in different sporting activities. For example, it is often presumed that women go to the gym for cardio and muscle-toning activities, whereas men go for weightlifting and muscle-building activities.

Figure 3.8 shows two very different gym setups, as mentioned above these tend to be gendered spaces that are more designed for different genders.

The gym floor organization can reinforce these presumptions as seen in figure 3.8: many gyms have weightlifting sections used by more men than women, and cardio sections, with smaller weights often placed alongside cardio equipment, which more women use. Sports equipment, especially weight training equipment, is often designed and arranged in a way best suited for an average male individual, especially regarding body size and height. For example, gym equipment such as the leg press or bench press may not allow shorter people—including non-binary people, many women, and shorter men—to adjust the height low enough to achieve an appropriate range of motion. At the same time, equipment like chin-up bars may be positioned too high for shorter individuals to reach.

Many sports facilities, especially swimming pools, are often large open spaces that require people to expose their bodies. Many gyms also have large wall mirrors that expose the body. Swimming pools may also have clothing restrictions such as rules banning the use of T-shirts and other loose clothing in the water. Many people are uncomfortable with exposing their bodies in public places due to gender dysphoria and cultural or religious reasons. The body exposure required by these spaces can be a significant barrier, making people unwilling or unable to use sports facilities.

Many sporting communities, including sports clubs, teams, and training groups are gender-segregated. To be a member of a sporting community, people usually need to choose to enter either a men’s or a women’s sports group. This is a significant challenge for non-binary people. Moreover, sporting communities are often characterized by gender norms and presumptions about women and men. These can be both explicit and implicit, but they are expressed in the kinds of activities people engage in and the way they talk to each other and about each other.

In men’s sporting communities, these norms and presumptions can manifest in gendered behaviors, expressions, and slurs like “you throw like a girl,” “boys don’t cry,” and “grow some balls.” This includes the so-called “locker room talk,” such as sexually loaded banter about women and mockery of gay men, including the presumption that gay men are more feminine than other men. They can also manifest in more subtle gender stereotypes and expectations that may not be put in words, such as the presumption that “real” men are big and strong, which then implies that men who are smaller and less strong are not real men.

In women’s sporting communities, on the other hand, gender norms and presumptions can manifest through gender policing. In other words, women often evaluate themselves and each other against norms about what women should look like, especially in gender-segregated spaces like women’s changing rooms (Agarwal, 2022). If a person with a more masculine appearance enters a women’s changing room or other women-only space, this person can experience harassment or even be asked to leave. This happens not only to non-binary people but also to trans women and other gender-diverse people, such as women with more masculine gender presentations.

Women-only spaces are often considered safe spaces where women are protected from sexual harassment and violence from men. However, the effect is that non-binary and other gender-diverse people can feel uncomfortable, excluded from, and even harassed in these spaces. Binary gender norms, stereotypes, and presumptions that characterize many sporting communities can be a barrier, not just for non-binary and other gender-diverse people, but for men and women as well. They can lower women’s self-confidence and create gendered behavior expectations that many men also find damaging.

3.4.3 Plastic Surgery

Many people attempt to place themselves into the position of looking like the idealized body and facial types seen in media and society. We will further discuss the socialization of gender in media in Chapter 10. Figure 3.8 shows a summary of the most prominent plastic surgeries that meet idealized expressions of gender. As the chart shows, plastic surgery to become more hyperfeminine, more “whitewashed,” and appear younger are the top 10 procedures. This is a long-holding pattern in plastic surgery and comes directly from the impacts of societal structures that place a large weight on appearances, especially those of women.

| Top Five (Invasive) | 2019 Numbers | Increase/Decrease |

|---|---|---|

| Breast Augmentation | 299,715 | -4% |

| Liposuction | 265,209 | +3% |

| Eyelid Surgery | 211,005 | +2% |

| Nose Reshaping | 207,284 | -3% |

| Facelift | 123,685 | +2% |

Figure 3.9 the top five plastic surgeries and top five less invasive cosmetic surgeries.

3.4.4 Activity: What Is Victoria’s Secret?

Watch this TikToker’s video “Victoria’s Secret” and then consider the questions below.

- What message is Jax sending out to society through this message?

- Do you think that this version of a video is inclusive and open to those who feel pressure to look like a certain version of their gender?

- What connections can you make from the ideas and discussions in this section to consumerism, capitalism, and those who hold power?

- What things do you think you as a person, your group, workplace, institution can do to shift the pressures of these idealized gendered expressions for the well being of all?

3.4.5 Licenses and Attributions for Embodied Gender

First paragraph of “Idealized Body Type and Size” is adapted from “Ability, Intersectionality, Body Image, and Reclaiming Our Bodies” by Ericka Goerling, PhD and Emerson Wolfe, Introduction to Human Sexuality, which is licensed under CC BY-NC-SA 4.0.

“Fitness and Gym Culture” is adapted from “Non-Binary Inclusion in Sport” by Helen spandler, sonja erikainen, al Hopkins, jayne Caudwell, Han newman, lauren whitehouse, which is licensed under CC BY 4.0.

Figure 3.6a. “Manufactured only by the Bortree Manufacturing Company. Adjustable Duplex Corset. [front]” by Boston Public Library is licensed under CC BY 2.0.

Figure 3.6b. “How foot-binding deforms the foot” by quinet is licensed under CC BY 2.0.

Figure 3.6c. “Red overknee boots on high heels, red mini skirt” by Kostya Romantikov is licensed under CC BY-NC-ND 2.0.

All other content in “Embodied Gender” by Heidi Esbensen is licensed under CC BY-NC-SA 4.0.