3.5 Sexuality

In sociology, sexuality is studied and described in ways that look at sexual attitudes, norms, practices, and social implications. Sexuality is simply who a person is attracted to, and it is commonly viewed as a social construct. It’s a cultural universal, meaning sexuality exists in most societies and cultures worldwide and throughout time. Sexuality may look different over time, as most things do. Sociology recognizes that norms, values, interactions, expectations, and ideas of what things mean shift and change over time throughout societies; sexuality is no different.

What we view as “normal” in terms of location, time, age, and culture changes over time. If you live in a very liberal and accepting area of society, your understanding and acceptance of sexuality may look very different than if you live in an area that is much more conservative and less accepting. Being open about one’s sexuality can be dangerous in one area, and celebrated in another. The table in figure 3.9 provides an overview of sexual identities with a link to a more comprehensive list.

| Term | Definition |

|---|---|

| Asexual | Used to describe people who do not experience sexual attraction or do not have a desire for sex Many experience romantic or emotional attractions across the entire spectrum of sexual orientations. Asexuality differs from celibacy, which refers to abstaining from sex. Also ace, or ace community. |

| Bisexuality | A person emotionally, romantically, or sexually attracted to more than one sex, gender or gender identity though not necessarily simultaneously, in the same way, or to the same degree. |

| Demisexual | Someone who feels sexual attraction only to people with whom they have an emotional bond—often considered to be on the asexual spectrum. |

| Gay | Used to describe people (often, but not exclusively, men) whose enduring physical, romantic or emotional attractions are to people of the same sex or gender identity. |

| Heterosexuality | Used to describe people whose enduring physical, romantic, or emotional attraction is to people of the opposite sex. Also straight. |

| Lesbian | Used to describe a woman whose enduring physical, romantic, or emotional attraction is to other women. |

| Pansexual | Used to describe people who have the potential for emotional, romantic or sexual attraction to people of any gender identity, though not necessarily simultaneously, in the same way, or to the same degree. 33 The term panromantic may refer to a person who feels these emotional and romantic attractions but identifies as asexual. |

| Queer | Once a pejorative term, a term reclaimed and used by some within academic circles and the LGBTQIA+ community to describe sexual orientations and gender identities that are not exclusively heterosexual or cisgender. |

| Same-gender loving | A term coined in the early 1990s by activist Cleo Manago, this term was and is used by some members of the black community who feel that terms like gay, lesbian and bisexual (and sometimes the communities therein) are Eurocentric and fail to affirm black culture, history, and identity. |

Figure 3.10. An incomplete list of sexual identities. For more and a deeper understanding of different sexualities, please visit The Acronym and Beyond | Learning for Justice

3.5.1 Studying Sexuality

Sexuality can be described as a person’s capacity for sexual feelings, and sexual orientation is derived from who those sexual feelings are directed toward. For example, a cis woman attracted to cis men would likely be categorized as heterosexual, or a man attracted to other men would be referred to as homosexual or gay. Acknowledging the need for each person to define their own identities is highly important, including the identity of not having a sexual attraction to others, otherwise known as asexual.

The difficulty with sexuality in the United States is the ability to measure it accurately because the definition of sexuality has fluctuated and changed over time. Sexuality is understood and interpreted differently by different people. The problem is getting a representative measure of populations with varied sexuality. When a survey asks about one’s sexuality, there are many different interpretations of the provided terms. Some people are asexual but consider themselves gay, so having intimate relations isn’t relevant in that instance. Or maybe someone identifies as queer sexually but only dates people of the same gender, like a woman who only dates cis-women or only dates trans-women. Or what about someone who identifies as heterosexual or straight but has sexual relations with other genders privately or for money? The variations on sexuality, even in terminology, range across age, regions, social groups, and identity.

The second issue with understanding sexuality in the context of populations relates not only to the above definition differences. We must consider whether respondents to surveys and studies feel safe enough to disclose their identities. Even if a survey is random and anonymous, it can feel dangerous for many non-heterosexual individuals. Some may not be in a place where they accept their own identity based on social norms and the expected sexuality. Overall, the estimates from studies and national surveys represent the population identifying as certain sexualities. However, many believe they are underestimating the population size and that the number of non-heterosexual individuals is much higher.

3.5.2 Sexuality in the US

Now that we have explored sexuality from a social construction lens let’s look at sexuality in the United States. The majority of people in the United States identify as heterosexual (Census.org, Gallup Polls, 2022) or are attracted to the opposite sex—biologically speaking—so this is where we see the norms and behaviors that guide most societal expectations and expressions of sexuality.

Remember when we looked at compulsory heterosexuality in the United States in Chapter 1? This is a social construction of sexuality in which heterosexuality and heteronormativity are expected and celebrated in the United States. However, we saw other norms and behaviors around sexuality practice in cultures across the globe.

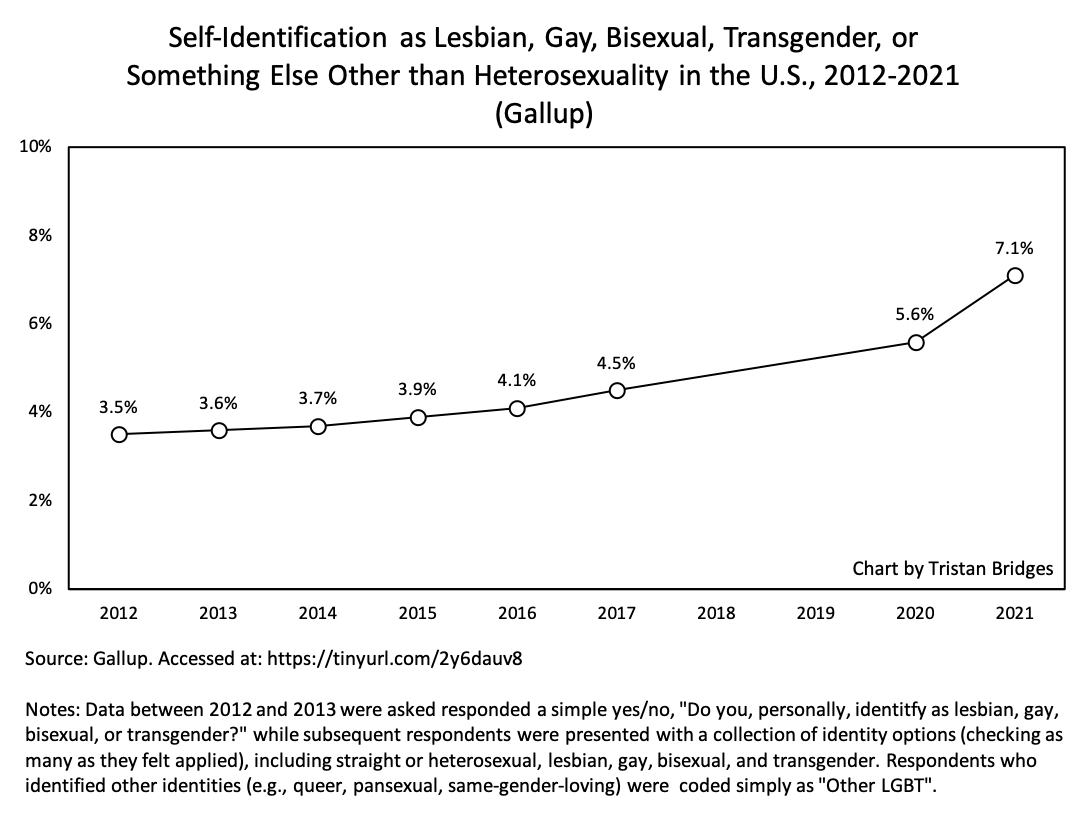

Let’s examine what changed in the United States regarding sexuality and whether that is guiding us to a new space. Even though a majority of the population identifies as heterosexual or straight, there’s been a recent increase in other sexual identities (figure 3.11). Let’s look at why that is.

Figure 3.11. Shows the increase in sexuality through Gallup Polling from 2012-2021

The increase in individuals identifying with non-heterosexuality is not due to a recent uptick in more varied gender attraction but rather the acceptance of general society in welcoming and representing people with non-hetero sexualities. The more we can “see” people like us, the more we are likely to “be” who we are openly. Non-heterosexual individuals have always existed in these numbers, but for a variety of reasons, were not comfortable being themselves to society until recently. Part of this is due to heterosexism, or discrimination or prejudice against gay people on the assumption that heterosexuality is the normal sexual orientation.

Looking at the social norm 50 years ago, where homosexuals were outcast, harassed, attacked, murdered, etc., we can understand why many would not “come out.” Examples of these would be laws and policies discriminating against homosexual individucals in the militarythe Stonewall riots in 1969 (1969 Stonewall Riots – Origins, Timeline & Leaders – HISTORY), While not all of the discrimination, harassment, assault, and judgment have disappeared, it has lessened somewhat. Those who identify as “not straight” are much more visible and have many more rights than 50 years ago. Those who “appear ” not straight or do not ascribe to a binary gender ideal are still at very high risk of assaults and attacks. According to PFLAG hate crime statistics releases hate crimes based on gender identity increased from .5% to 1.8% and sexual orientation still sits at 18.6% down from 20.8%. This does not account for those attacks that are not reported or not flagged as hate crimes (PFLAG, 2022). Across the United States, more individuals are willing to be open about their sexuality, even in light of that fact. This show of strength and solidarity, in turn, encourages more people to share their LGBTQ+ lifestyles.

3.5.3 Sexuality and Social Change

Empowerment and social change situations continue to shift the dynamics of what is normal, what is accepted, and what occurs around sexuality in the United States. We can see some of this in popular culture through films, television, and music. Social movements such as #metoo and Slut Walks show the shifting dynamics of change around power, gender, and sexuality. For women and members of the LGBTQIA+ community, this is a movement in a positive direction, allowing them to take more agency and use their sexuality in a powerful way.

These seismic societal shifts also tend to cause backlashes from those who disagree with non-hetero sexualities and their expression. As more LGBTQIA+ people gain prominence and power in society, the younger generations, in particular, have felt the negative effects of those wishing to preserve the status quo.

3.5.4 Sex Education

Now, let’s look at sex education in terms of how it is taught, when it is taught, and what is taught—if it is taught at all. Let’s start with this 11:49 minute video of the history of sex education in the United States and why it has been left for schools to educate children on sex, sexuality, and sexual health instead of being taught within the family structures:

Figure 3.12 Video on sex ed in the United States and why it is part of school curriculum.

Unlike in other countries, such as Sweden, sex education is not required in all public school curricula in the United States. The heart of the controversy is not about whether we should teach sex education in school as we will see below; it is about the type of sex education we should teach.

Much of the debate is over the issue of abstinence and what topics should be taught. In a 2005 survey, 15 percent of U.S. respondents believed schools should teach abstinence exclusively and not provide contraceptives or information on how to obtain them. Forty-six percent believed schools should institute an abstinence-plus approach, which teaches children abstinence is best but still gives information about protected sex. Thirty-six percent believed teaching about abstinence is not important and sex education should focus on sexual safety and responsibility (NPR 2010).

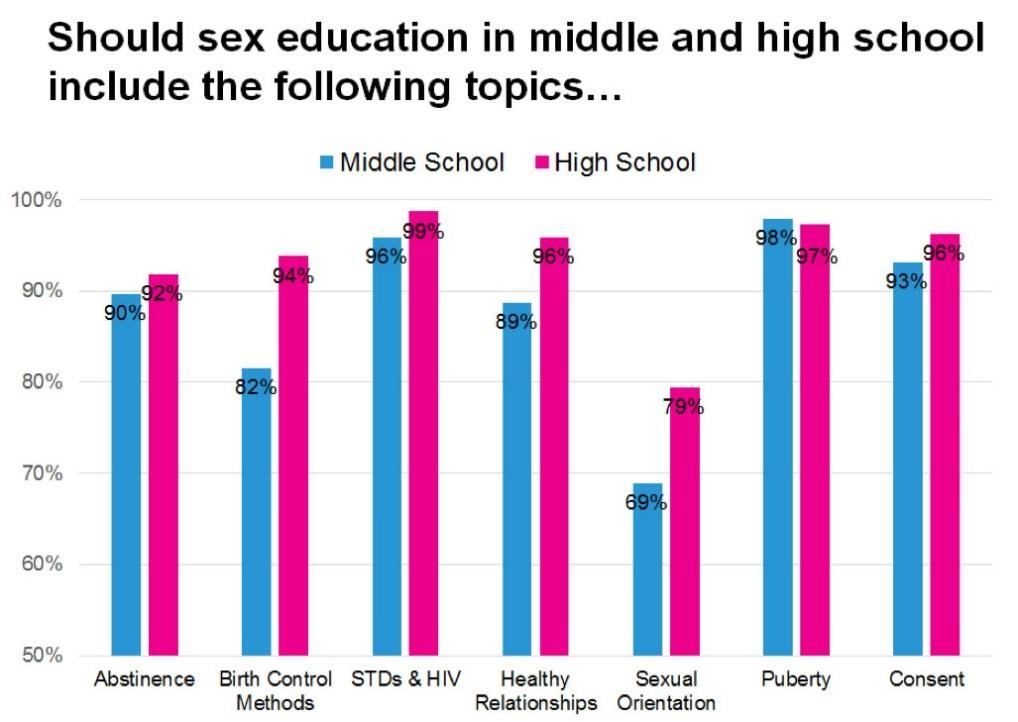

Research suggests that while government officials may still be debating the content of sex education in public schools, the majority of U.S. adults are not. Those who advocated abstinence-only programs may be the small, but loud groups regarding this controversy since they represent only 15 percent of parents. The chart below shows that most people would like a wide variety of related topics taught in sex education, including abstinence.

Figure 3.13. This chart shows that a majority of a representative sample in the US thinks most of these topics (abstinence, birth control, STDs, healthy relationships, sexual orientation, puberty, and consent) should be included in sex ed curricula.

Since the 1980s, sex education has focused on an abstinence-based, or abstinence-only until marriage, model. This approach to sex education promotes sex as an act between two heterosexual, cisgender persons after getting married. Further, same-sex attraction is taught to be feared, and gender stereotypes are reinforced. Public health organizations and most parents agree that sex education should include discussions of LGBTQIA+ identities.

In reality, less than 4 percent of LGBTQIA+ youth reported any mention of sexual or gender orientation in their health classes, and only 12 percent were told about same-gender relationships. The routine omission of LGBTQIA+ issues from sex education curricula constitutes a violation of adolescent human rights (Gowen & Winges-Yanez, 2014; Jones & Cox, 2015; Miller & Schleifer, 2008). It is a violation because it “robs youth of sexual agency by withholding information that is critical to health and well-being” (Elia & Eliason, 2010). Whether habitual or deliberate, the omission of LGBTQIA+ topics from health curricula implies that sexual and gender fluidity is not part of the natural biological order and is, by default, unnatural or perverse (Bay-Cheng, 2003).

When discussions of LGBTQIA+ issues appear in health textbooks, the language shifts toward these persons as the “other.” Some health textbooks present the sexual experiences of LGBTQIA+ youth as vastly different from those of heterosexual and cisgender youth (Whatley, 1994). LGBTQIA+ youth do have some differences in sexual experiences and including information tailored to their needs helps reduce the risk of sexually transmitted infections. Sex education that affirms LGBTQIA+ youth delays the age of first sexual intercourse and a reduction in the following:

- unintended teen pregnancy

- rates of HIV and other sexually transmitted infections

- overall number of sexual partners

- unprotected sex while increasing condom and contraception use

The comprehensive sex education program in Sweden’s public schools educates participants about safe sex and can serve as a model for this approach in the United States. The teenage birth rate in Sweden is 5 per 1,000 births (worldbank.org, 2020), compared with 16.7 per 1,000 births in the United States (CDC, 2019). Among 15 to 19-year-olds, reported cases of gonorrhea in Sweden are nearly 600 times lower than in the United States (Grose, 2007).

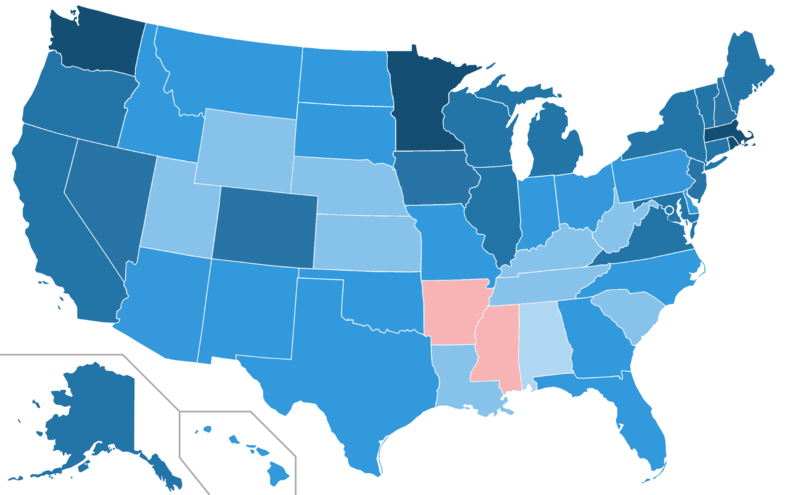

Using the sociological perspective, a sociologist would want to look at the correlation between sex ed curricula and outcomes such as teen pregnancies and STDs. What does Mississippi sex ed legislation look like? Mississippi has the highest teen pregnancy rates in the United States, with 28 births per 1,000 women ages 15-19. Arkansas, Louisiana, Oklahoma, and Alabama are next in line with around 25 births per 1,000 women ages 15-19 (CDC 2022). What does sex ed look like in those states? Is there a correlation? What other factors influence teen pregnancy in these states?

3.5.5 Policies and Institutional Inequality

Perspectives on heteronormativity influence daily interactions and structures in our society as well as gender norms and expectations. One of those is marriage equality, or all people having the same rights and responsibilities regardless of their gender or sexual identity. In terms of relationships and marriage, it was not that long ago, gay men and women could not marry legally in most of the United States. Only as of 2015 was it legal for same-sex, same-gender couples to marry. Before the Supreme Court ruling, same-sex marriage was legal, but only in certain states, and federal legal rights were not guaranteed. Massachusetts was the first state to grant same-sex marriages back in 2004, but that had many barriers to equal protection under federal law.

Today, there’s a possibility of the Supreme Court overruling the legality of same-sex marriages, which would be catastrophic for the LGBTQIA+ community. This type of ruling would also go against public perspectives. In the figure below (figure 3.X), most Americans support gay marriage by a significant percentage.

Image 3.14 This map shows public opinion of same-sex marriage in the United States by state and Washington, D.C. in 2021.

| Majority support same-sex marriage — 80-85% | |

| Majority support same-sex marriage — 70-79% | |

| Majority support same-sex marriage — 60-69% | |

| Majority support same-sex marriage — 50-59% | |

| Plurality support same-sex marriage — 40-49% | |

| Majority oppose same-sex marriage — 50-55% |

More information and data on same-sex marriage and public opinion can be found in this recent Gallup poll

Marriage equality did not exist for same-sex couples until 2015, making this a new shift towards equality, given the historical patterns of the United States. Why was same-sex, same-gender marriage against the law and unaccepted in society? Dominant groups work very hard to promote their interests and ideology. Allowing same-sex couples to marry, through those dominant narratives, contradicts the ideals of “marriage” and puts at risk what is felt to be sacred and takes place solely between a “man and a woman.”

An easier way to view this is through the lens of conflict theory, which focuses on the competition among groups within society over limited resources. Conflict theory views social and economic institutions as tools of the struggle among groups or classes, used to maintain inequality and the dominance of the ruling class.

For conflict theorists, there are two key factors in the debate over marriage equality—ideological and economic. Dominant groups wish for their worldview—which embraces traditional marriage and the nuclear family—to win out over what they see as the intrusion of a secular, individually driven worldview. On the other hand, many LGBTQIA+ activists argue that legal marriage is a fundamental right that cannot be denied based on sexual orientation. Historically, there already exists a precedent for changes to marriage laws: the 1960s legalization of formerly forbidden interracial marriages is one example.

From an economic perspective, activists in favor of same-sex marriage point out that legal marriage brings with it certain entitlements, many of which are financial in nature, like Social Security benefits and medical insurance (Solmonese 2008). Denial of these benefits to same-sex couples is wrong, they argue. Conflict theory suggests that as long as people struggle over these social and financial resources, there will be some degree of conflict.

We find ourselves again in a place where marriage equality will be challenged in the highest court in the United States, so the debate and conflict aren’t over, even after an institutional and legal precedent was placed in support of marriage equality almost eight years ago. This brings us back to the deeply institutionalized norms and values of what is acceptable and what would maintain the power dynamics and privilege of the dominant classes.

3.5.6 Activity: Same-Sex, Same-Gender Marriage

Figure 3.15 Screenshot from Obergefell V Hodges explained.

Please watch the video Obergefell v. Hodges Explained and come back to answer the following questions:

- Thinking of the historical freedom to marry (where it was not a woman’s right per se for a long time), what social perspectives have allowed this right to be in question and what social perspectives continue to make some question this right?

- Looking at the dissenting opinion of the four judges, they cited that states should independently hold votes and have popular votes decide whether the state should allow same-sex marriages. What effects do you think this would have federally? What about in states that would vote no?

- As we look at the new abortion laws that are leaving those decisions up to the state, what impact can you imagine would happen if this decision is overturned? What rights would same-sex couples lose if their ‘state’ decided their marriage was illegal?

3.5.7 Licenses and Attributions for Sexuality

“Sexuality” is adapted from “Sexualities” by Miliann Kang, Donovan Lessard, Laura Heston, Sonny Nordmarken, Introduction to Women, Gender, Sexuality Studies, which is licensed under CC BY 4.0.

The first part of “Sex Education” is adapted from “Reading: Sex and Sexuality” by Lumen Learning, Sociology, which is licensed under CC BY 4.0.

Four paragraphs of “Sex Education” is adapted from “Education and LGBTQ+ Youth” by Kimberly Fuller, Introduction to LGBTQ+ Studies: A Cross-Disciplinary Approach, which is licensed under CC BY 4.0.

Last two paragraphs of “Sex Education” is adapted from “Sex and Sexuality” by Lumen Learning, Introduction to Sociology – Brown-Weinstock, which is licensed under CC BY 4.0.

Figure 3.11. “Self Identification as Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Transgender, or Something Else Other than Heterosexuality in the U.S. 2012-2021 (Gallup) by Tristan Bridges, Shifts in Gender and Sexual Identities in the U.S. – 2022 Update, Inequality by (Interior) Design is included under fair use.

Figure 3.15. “Obergefell v. Hodges Explained” by Zack Attack is licensed under the Standard YouTube License.

All other content in “Sexuality” by Heidi Esbensen is licensed under CC BY 4.0.