4.3 Global: Interlocking Systems

The concept of intersectionality has been described and developed by BIPOC poets, activists and scholars to describe the multiple impacts of systems of oppression. Students of sociology will recognize the work of Angelea Davis (2011), Audre Lorde (2011), Kimberlē Crenshaw (1991), and Patricia Hill-Collins (1990) to describe the experience of Black women and black queer women in terms of intersecting identity and power.

In the 1970’s a group of radical Black women came together to form the Combahee Women’s Collective to address specific political positionality of working class black lesbians, often overlooked by white feminists and Black Civil Rights workers. The Combahee River Statement, published in 1977 became a foundational text of Black Feminism and radicalism more generally. In it they described and analyzed the specific experiences of Black working class lesbians working for collective liberation, and called for coalition building that centers the well-being of people impacted by multiple interlocking systems of class-based oppression, racism and sexism (Anzaldúa & Moraga, 1977; Taylor, 2017).

Figure 4.6. Native Land Digital Fair use license.

It’s important to not only think about the past, but also how the past influences the present and is shaping the future. Native Land Digital is a website and app dedicated to Indigenous issues around the world and the legacy of colonialism (figure 4.6). In this section, we’ll look at the ways that colonialism, patriarchy, and White supremacy are part of global interlocking systems of oppression, and how they impact on nonbinary, trans, gender non-conforming, and other experiences throughout the world.

While looking at figure 4.6, what can you imagine would be different about gender expression today if settlers to a new area had listened and respected native voices? We’ll talk about the violence of annihilation later in this chapter.

4.3.1 Colonialism

Colonialism is a system of power based on the conquest of populations and the control of territory by a state or empire. The domination of indigenous populations, the theft of lands, and the exploitation of waters and resources by a conquering society is central to the function of colonialism. (Alfred and Corntassel 2005; Wolfe 2006).

Global exploration and the emergence of European dominance in global trade, beginning in the 15th century, enabled the rapid expansion of European empires. Spain, Portugal, Denmark, France and England engaged in a fierce race to conquer and colonize the Americas, Asia, Oceania and the African Continent. As European economic and political dominance expanded, European norms, behaviors, and values, including heteronormativity were imposed on conquered populations. New ideas about racial classification and capitalism emerged to justify and normalize the domination and exploitation of colonized populations and their wealth. The intersection of these concepts has been recently referred to as Colonial Racial Capitalism (Koshy et al. in 2022) and incorporates religion, language, politics, economics, and the desire for real power.

These systems of power require strict adherence to gender norms and socio-economic class in order to continue providing the best output for the ruling elite. This eventually results in internalized feelings of inferiority for the dominated and superiority for the dominating population, and by the subjugated population as well (Lugones 2016). More on the history of capitalism and its relationship to colonialism can be found here.

The combination of these systems sustains itself by strengthening an individual’s access to resources as a reward for compliance. When one conforms in a particularly gendered way, such as men being perceived as “macho” and “determined”, they are rewarded by society with higher pay and larger social groups. When women conform to a stereotypical ideal of womanhood, they are rewarded with praise for being “such a great role model”. There can be serious repercussions for non-compliance, however, such as the violence transgendered folks regularly experience for simply trying to use a public restroom, or “less attractive” actors not being cast for roles. Social scientist Lucas Ballestin called how we have perceived gender for the last several hundred years as a “colonial object” (Ballestin, 2018), or as a specific left-over of the institution of colonialism and the consolidation of power and social control in Europe in the 18th century. An excellent resource on the general background of colonialism and its role in upholding oppressive systems is the article “Fish, People, and Systems of Power: Understanding and Disrupting Feedback between Colonialism and Fisheries Science.”

4.3.2 Patriarchy/heteropatriarchy

Patriarchy is a system of society or government in which the father or eldest male is head of the family, with descent (or who you’re related to) traced through the male line. Within patriarchal systems, women are collectively excluded from full participation in political and economic life. Those attributes seen as ‘feminine’, or as pertaining to women are undervalued. Patriarchal relations structure both the private and public spheres, with men making the important decisions, or “holding the reins of power” in both domestic and public life (Nash, 2009).

Feminist scholarship has theorized linkages between patriarchy and capitalism, colonialism and nationalism, which argues that patriarchal relations operate across and between a number of systems in ways that reinforces the system that lets men stay in charge. In feminist theory, heteropatriarchy (a merging of the words heterosexual and patriarchy) is a socio-political system where cisgender and heterosexual males have authority over everyone else. This term emphasizes that discrimination against women and LGBTQIA+ people is derived from the same sexist social principle (Nash, 2009).

Feminist theory focuses on the issue in heteropatriarchal societies, highlighting the fact that cis-gendered, heterosexual men generally occupy the highest positions of power in society, causing women (including transgender women), non-binary people, transgender men, and other LGBTQIA+ people to experience the bulk of social oppression. Examples can include women being punished in the military for having “too short a haircut”, the fact that single mothers are more likely to make under the poverty line than single dads (We Are All Victims of a Patriarchal Society: Some Just Suffer More than Others, n.d.), and that trans women were murdered at higher rates than any other queer demographic in 2022 (Schoenbaum, 2022).

It is important, however, to remember throughout this discussion the intersections of gender, sex, race, economic status, and disability, and other forms of oppression and discrimination. For example, cis-gendered, poor, White gay men experience different types of oppression compared to Black trans women. By recognizing differences in lived experience amongst different groups and the connections they might have to each other, we can begin to figure out how to dismantle each of these types of oppression.

4.3.3 White Supremacy

Racism is a stratified system of power, based on socially constructed ideas about race that create and normalize racial inequity (Kendi, 2017). White supremacy is a racist idea that people who are racially categorized as White are superior to people who can be identified by darker skin and other racialized characteristics. White supremacy, like other racist ideas, is based on domination and exclusion. Colonial Racial Capitalism, a system of power that relies on white supremacy to justify the domination of black and brown people and the exploitation of resources in colonized regions (Koshy et al. 2022). Capitalists argue that capitalist economies are rational, unbiased, and self-regulating. Yet the current global capitalist system has been and remains empowered by white supremacy and colonialism (Nguyen 2020).

Argentine feminist philosopher Maria Lugones (2016) discusses the intersection of White supremacy and gender expression in her work. She explains that gender and the “correct” performance of gender were used as a tool of colonialism to justify conquering, killing, and subjugating people and claiming their resources. By having exclusionary categories that narrowly define who is a “proper person,” the system can more easily exploit and plunder resources for the benefit of the few.

Defining a racialized gender binary and enforcing rigid norms within those categories (men had to act like “proper white men,” women had to act like “proper white women”) is the way capitalism and colonialism work together to control the population. This allows the elite to continue to take or absorb resources and wealth not only from subaltern populations but also from elite societies. To have any chance of “moving up” in society, one must conform to their exact category of race, age, ability, gender, and social class to benefit from the system. To challenge these systems in any way risks one at risk to be ostracized, stripped of social standing, income and even housing. Because such an association can also impact a social family’s standing, families become the primary enforcers of gender normativity.

In the 19th century, homosexuality, while technically illegal, was an open secret. As long as Wealthy white men gave the illusion of dating women or were renowned as a “gentleman bachelor,” the fact that they lived with a long-term roommate or lived did not preclude them from race- and class-based privilege. Wealth and white privilege could not shield gay men if their personal transgressions were not perceived as a threat to the social order. Although the law was seldom used against wealthy white men, Oscar Wilde, an Irish playwright, was arrested and convicted in 1985 for homosexuality when his lover’s wealthy father sought to save his family’s reputation from the social consequences of raising a homosexual son.

Arthur Conan Doyle, the author of the Sherlock Holmes stories, and a contemporary of Wilde knew exactly how the public would view two white wealthy gentlemen living together. However, by avoiding “queer coding” that subtextually signaled gayness in his literature Doyle gave his characters the ability to maintain their racial and class privilege, and their acceptability to his audience. (We will learn more about queer coding in Chapter 10).

According to scholars of white supremacy, the long-term goal of challenging white supremacy is directly tied up with the project of dismantling the capitalist market system (Lugones 2016). Such a project requires reimagining systems of power that benefit everyone without resorting to exploitation, domination, or conformity to false-binaries.

4.3.4 Impact on Non-Binary Identities and Third Genders

There are many examples of non-european societies that maintain otherwise rigid norms around sexuality and gender expression and also allow for specific cultural spaces that accommodate the non-normative lived experience of individuals. Many religious systems, including pre-christian european religions, recognize deities that are gender fluid and or gender expansive. In these cases, it is easier to understand non-binary sexuality and genders are reflections of aspects of the deities or of the cosmos itself, and that people who manifest non-binary aspects of deity as essential to society.

White missionaries and colonizers have historically been quick to impose even more rigid forms of hetero-patriarchy, based on their own hetero-patriarchal deity. The association of some non-binary identities with socially tolerated sex work further inflamed the missionaries efforts to violently suppress trans and non-binary gender expressions and sexuality though conversion and legislation reforms. In spite of this violent erasure, contemporary trans, non-binary, and same sex-loving people in formerly colonized societies are struggling to reclaim and reinvigorate their traditional cultural norms around gender and sexuality.

4.3.4.1 Muxe (Mexico)

The Muxes (pronounced mu-shay), a recognized third gender among the Zapotec people in Oaxaca, Mexico, maintain traditional dress, the Zapotec language, and other cultural traditions that are less prevalent among the broader Zapotec community.

Figure 4.7. Zapotec Muxe contemporary performance artist from Mexico. Image © Mario Patinho. Used with permission

Many sociologists believe that the wider acceptance of a third gender among the community may be traced to the belief that individuals who identify as Muxes are part of and not separate from their overall culture and traditions (Natural History Museum, n.d.).

4.3.4.2 Hijra (India)

Hijra, who have been widely referenced in Hindu literature dating back to the 4nd century B.C, have maintained a constant but subaltern presence in Hindu society. Hijras experienced extreme persecution under the British Empire. In spite of this marginalization, Hijras continue to play important roles in Hindu religious ceremonies, including the blessing of marriages and births. Hijra ashrams operate as religious orders and as refuges of relative safety where people assigned male at birth can embody an expansive third gender (Nanda, 1998).

In contemporary India, where hetreo-normativity is still rigidly enforced, Hijras, men who love men, but do not identify as Hijra, and women who love women are still subject to violence and persecution, but the visibility and activism of Hijras and other LGBTQ people in India are successfully challenging rigid gender norms. An Indian friend of the author tells of a lesbian friend coming out to her parents, who were mostly okay with her marrying a woman, but still insisted that they be allowed to select her bride in the traditional way.

In 2014, the supreme court in India responded to Hijra activism creating a legal designation of third gender in recognition of hijras, which also extended to other trans and intersex people. Pakistan, Nepal and Bangladesh also recognize a third gender. The activism has not stopped with this win either, the colonial-era law prohibiting sex between people of the same gender was struck down in 2018, and as of this writing, a case to legalize same sex marriage is being considered by the Indian Supreme Court (NPR, 2023).

Figure 4.8. A group of Hijra posing for a picture. By USAID – USAID Bangladesh, Public Domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=35623308

4.3.4.3 Two-spirit (North America)

The Anishinaabemowin (Ojibwa) term niizh manidoowag translates to English as “of two spirits”, and traditionally refers to a gender expansive identity that ecompasses both male and female qualities or to a third gender (The Canadian Encyclopedia, n.d.)”. Since its emergence in the contemporary indigenous culture in the 1990’s[1]. Many trans, non-binary and same-sex loving Native American people have embraced the identification of Two-spirit. As with Hijra and Muxe identities, this contemporary iteration of traditional third gender reaches back to more expansive pre-conquest cultural formations of gender and sexuality, and also references the spiritual implications of gender and sexuality.The contemporary usage of Two-spirit also highlights the importance of language preservation in recovering pre-conquest culture and ingenious ways of being (Smithers and Runner, 2022).

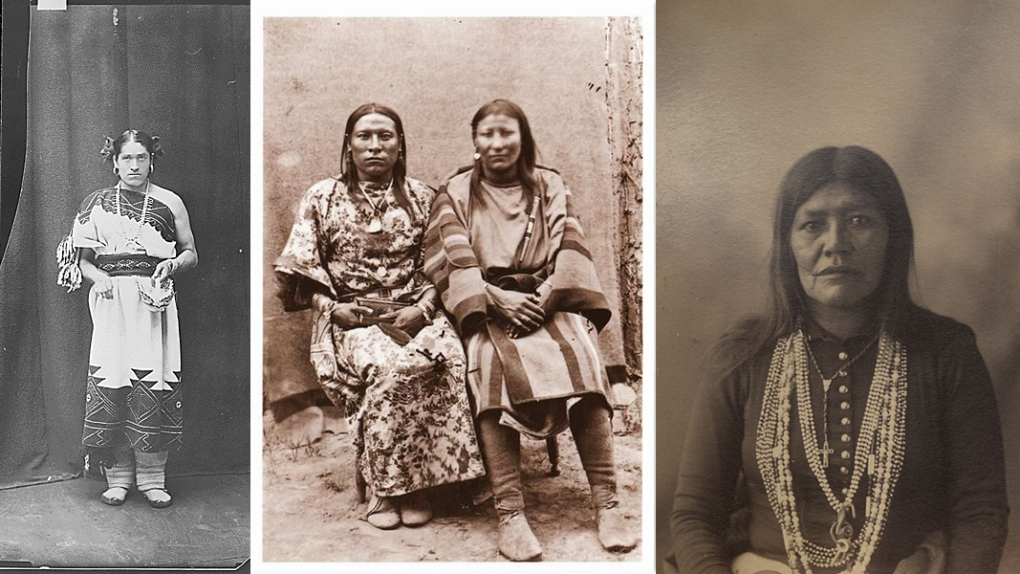

Figure 4.9a. We’wha (left), 4.9b. Osh-Tisch (center), 4.9c. Dahteste (right). (John K. Hillers, Image Courtesy of: Smithsonian Institute/John H. Fouch/F.A. Rinehart, Image Courtesy of Omaha Public Library)

4.3.5 Looking Through the Lens: Negotiating Same-Sex Relationships in a Heteronormative World

Margarete and Lynn (not their real names) are two wives living in the Pacific Northwest interviewed about their relationship. They’ve been a couple for 21 years, and have been legally wed since the U.S. Supreme Court struck down all state bans on same-sex marriage in 2015.

Figure 4.10 Are relationships really more egalitarian in a non-heteronormative household?

Straight couples have built-in cultural “rules” or norms to their relationship that they can lean on, so there’s little negotiating about who does the laundry or who washes the car. In queer relationships, however, those “norms” tend to not apply if both participants are women, both men, or one or both don’t identify as either (Miller, 2018).

As Lynn and Margarete do not have children, they still fit squarely into the “average” commuted queer relationship: there tends to be more income disparity in queer relationships than in straight ones (Lynn makes substantially more money than Margarete does).

Margarete agrees that queer couples have to communicate more about domestic labor, but she also argues that she thinks queer couples (in her experiences) are more engaged in the relationship in general than straight couples:

In my first marriage, my husband just expected me to do everything related to the house, because I worked from home and he made most of our income. There was no negotiating: he enforced the rules, based on how we grew up. With Lynn, we are so much more engaged emotionally and with the specific, I guess, logistics of life because we’ve had to talk out who fixes the broken screen door or who cooks dinner tonight. There’s no outside pressure from society telling us how those things should go – we’ve had to figure it out for ourselves.

After considering this couple’s relationship, answer the following questions:

- How does the intersection of income and gender roles play out in your own household?

- Look up “mental load.” How is this phenomenon affecting U.S. households today?

- How would having children change the division of labor?

- Can you find examples of how chores are gendered in other parts of the world?

4.3.6 Licenses and Attributions for Global: Interlocking Systems

“Global: Interlocking Systems” by Dana L. Pertermann is licensed under CC BY 4.0.

“Impact on Non-Binary Identities and Third Genders” by Nora Karena is licensed under CC BY 4.0.

Figure 4.6. Image © https://native-land.ca. Used with permission.

Image 4.7 Lukas Avendaño. Image © Mario Patinho. Used with permission under the Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 4.0 International Licence. – Muxe photo

Figure 4.8. A group of Hijra posing for a picture. By USAID – USAID Bangladesh, Public Domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=35623308

Figure 4.9a. We’wha (left), 4.9b. Osh-Tisch (center), 4.9c. Dahteste (right). (John K. Hillers, Image Courtesy of: Smithsonian Institute/John H. Fouch/F.A. Rinehart, Image Courtesy of Omaha Public Library)