6.8 Violence in Family and Relationships

Violence and abuse are among the most disconcerting of the challenges that today’s families face. Abuse can occur between spouses, between parent and child, as well as between other family members. The frequency of violence among families is difficult to determine because many cases of spousal abuse and child abuse go unreported. Studies show that abuse—reported or not—has a major impact on families and society as a whole.

6.8.1 Sexual Assault and Sexual Violence: Date and Marital Rape

Sexual violence occurs in all spaces, including dating and marriage. Sexual violence is not only a physical violation but is also about language, norms, and everyday behaviors perpetuated by society. We must understand the underlying issues, especially how these attitudes are ingrained in our current culture. Gender norms do not exist independently of most societal institutions, and sexual violence is no different.

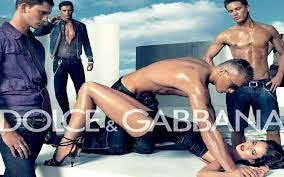

Figure 6.19 .A series of ads from Dolce and Gabbana that have since been banned, they explicitly depict sexual violence in several ways.

In the United States, sexual assault and rape are statistically underreported, and the corresponding data varies greatly. However, according to RAINN, each year, there are 463,634 victims of rape and sexual assault. Females have higher percentages of reported assaults, but 1 out of every 10 rape victims is male. Transgender, genderqueer, and gender non-conforming individuals are also at higher risk of rape and sexual assault than cis-identifying men and women.

What leads to these high numbers? Patriarchy creates these norms through matters of dominance and control and hegemonic masculinity, thus maintaining the status quo. We see this through the normalization of sexual violence in the media, socially, and politically, and in high-profile cases where the “boys will be boys” narrative is prominent. Brett Kavanaugh and Donald Trump are examples of prominent legal and political figures accused of multiple sexual assaults. To protect themselves from physical and sexual assault, young girls and women are taught to minimize discomfort and advances to avoid hostile situations with men. Normalizing this occurs in several ways, but the ones many will recognize are that:

- It wasn’t “legitimate rape” because the perpetrator didn’t finish, she liked it, or they know one another.

- It’s not rape if she didn’t say “no.” How hard someone fights back or not, how verbal she was or was not about it all factors into whether or not a victim is believed.

- It was her fault because of what she wore, how she looked, she was a tease, etc. (visit “What Were You Wearing?” Exhibit – DOVE Center Of St. George Utah for a powerful perspective on this)

- She was drunk and she should have been more responsible.

- Rapists are monsters and it was just one horrible person, not a systemic issue.

Read this article for more on the things women do that we don’t really think about: The Thing All Women Do That You Don’t Know About.

These ideas and norms also are barriers to reporting sexual violence. Society teaches us through these norms that reports will be dismissed and we won’t be believed if we step forward. We see this in the news and on social media. Many survivors lack trust in authority, assuming they won’t do anything. They might also want to minimize the incident to protect their own mental health, they might feel it was their fault, or that others will judge them if they speak up.

The Bureau of Justice Statistics (BJS) reports that most rapes and sexual assaults perpetrated against women and girls in the United States between 1992 and 2000 were not reported to the police by the victims. Only 36 percent of rapes, 34 percent of attempted rapes, and 26 percent of sexual assaults were reported.

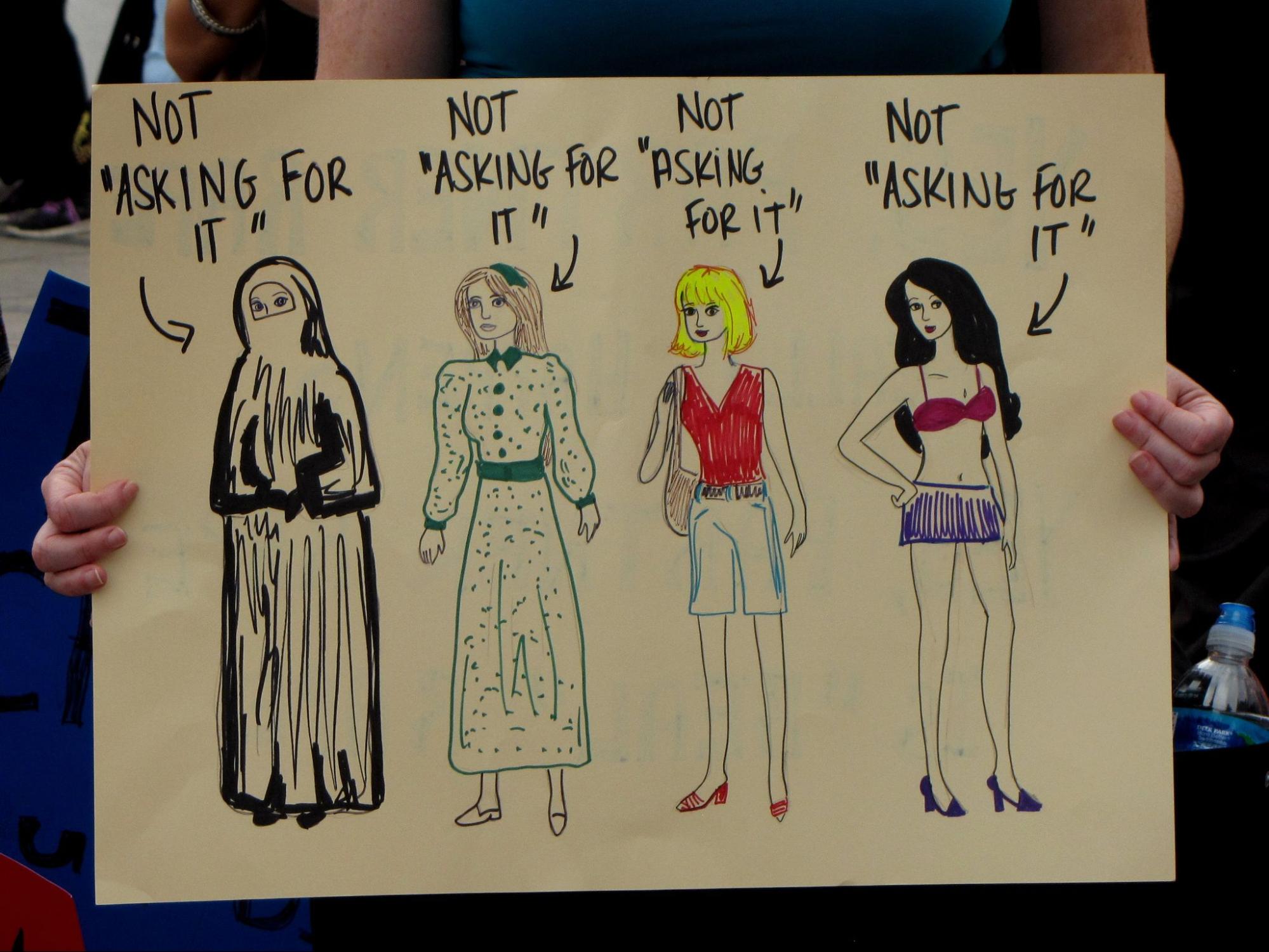

Sexual violence is not always about sex; it is often about control and dominance. The images below demonstrate how sexual assault is commonly excused and how victims are blamed.

Figure 6.20. Photos from a SlutWalk protest 2013 in DC, a protest and movement to fight against rape culture and sexual violence. For some context you can read “The SlutWalk Movement” by Joetta L. Carr.

Sexually explicit video games and online pornography create norms around behavior, which in those cases can be quite negatively impactful. The majority of pornography historically is made by men and for men, thus replicating norms of sexual violence and dominance. Research on this topic concluded that explicit video games and online pornography lead to increases in sexual violence and harassment (Guggisberg, 2020). Why do these add to the problems of sexual violence? They reinforce norms and acceptance of such behavior, they are readily available for many to see and are often only regulated through content warnings.

Research shows that men are also victims of sexual violence. 1 in 26 men reported being victims of completed or attempted rape at some point in their lifetime, compared to 1 in 4 women. In other words, about 14 percent of reported rapes involve men or boys. 1 in 6 reported sexual assaults is against a boy, and 1 in 25 reported sexual assaults is against a man. Men experience a particular culture of silence. Men are not “supposed” to be victims, especially in sexual relations. When asked about experiences in the last 12 months, 1.3 percent of men reported being “made to penetrate”—either by physical force or due to intoxication (CDC 2015/2016 ).

All genders experience significant barriers to reporting and coping with the trauma after an assault. Victims are criticized, ostracized, blamed, and made to feel as if the events were untrue, exaggerated, or they were at fault, either by not being strong enough, not saying no, or because of how they acted or how they dressed.

About half of all trans individuals and bisexual women experience sexual violence during their lifetimes. This is in some way connected and due to the higher risk factors such as poverty, stigma, and marginalization that lead to higher rates of sexual assault in populations. Another contributing factor to higher rates of sexual assault in the LGBTQIA+ community is hate-motivated violence, which can often take the form of sexual assault and sexual violence. There are also high rates of intimate partner violence and sexual assault from partners within the LGBTQIA+ community. Research suggests that several factors might play into the increased numbers of intimate partner violence including the social stigma of LGBTQIA+ relationships, the hyper-sexualization of the community, contradicting social norms, possible internalized homophobia, and shame about the relationships.

Data from the national CDC survey analysis (National Intimate Partner and Sexual Violence Survey) shows that bisexual women are at much higher risk in their lifetimes for all forms of sexual violence compared to heterosexual women, in some cases almost double or more. The same trend is seen when comparing bisexual women and lesbians, in that lesbians are also more likely than heterosexual women to face sexual violence. Bisexual and gay men also experience higher rates of sexual assault than heterosexual men. Some studies have shown that this increased risk may be linked to stereotypes of bisexuals, that they are incapable of having monogamous relationships, and there is also the likelihood that homophobia plays into this systemic issue. Trans individuals are also at higher risk of assault. The 2015 Transgender survey revealed that almost half of trans people are at some point in their lifetime sexually assaulted, with higher rates in those who are also BIPOC. We also see a trend that those who identify with the LGBTQIA+ community are less likely to receive access to services due to their sexual or gender identity. This also leads to even more hesitancy to report or seek care or services.

6.8.2 DV/IPV

Domestic violence is a significant social problem in the United States. It is often characterized as violence between household or family members, specifically spouses. To include unmarried, cohabitating, and same-sex couples, family sociologists have created the term intimate partner violence (IPV). (Note that healthcare and support personnel, researchers, or victims may use these terms or related ones interchangeably to refer to the same general issue of violence, aggression, and abuse.) Women are the primary victims of intimate partner violence. It is estimated that one in five women has experienced some form of IPV in her lifetime (compared to one in seven men) (Catalano 2007). IPV may include physical violence, such as punching, kicking, or other methods of inflicting physical pain; sexual violence, such as rape or other forced sexual acts; threats and intimidation that imply either physical or sexual abuse; and emotional abuse, such as harming another’s sense of self-worth through words or controlling another’s behavior. IPV often starts as emotional abuse and then escalates to other forms or combinations of abuse (Centers for Disease Control 2012). IPV includes stalking as well as technological violence (sometimes called cyber aggression), which is committed through communications/social networks or which uses cameras or other technologies to harm victims or control their behavior (Watkins 2016).

Figure 6.21. Many people have experienced intimate partner violence. Note that while data like this are important to consider and hopefully build awareness around IPV, there are gaps in both reporting and information gathering. For example, less information is known about IPV against transgender people, but analysis of various sources indicate that it is 1.7 times more likely to be committed against transgender people than against cisgender people, as described below. (Credit: Centers for Disease Control)

Beyond its tragic outcomes and damaging long-term effects, sociologists and other researchers seeking to understand and prevent IPV and support victims may find a wide variance in the data.

On a global scale, intimate partners kill over 130 women each day. The UN Office of Drugs and Crime reported that, “women continue to pay the highest price as a result of gender inequality, discrimination and negative stereotypes… They are also the most likely to be killed by intimate partners and family” (Doom 2018).

The types of violence can vary significantly according to gender. In 2010, of IPV acts that involved physical actions against women, 57 percent involved physical violence only; 9 percent involved rape and physical violence; 14 percent involved physical violence and stalking; 12 percent involved rape, physical violence, and stalking; and 4 percent involved rape only (CDC 2011). This is vastly different than IPV abuse patterns for men, which show that nearly all (92 percent) physical acts of IVP take the form of physical violence and fewer than 1 percent involve rape alone or in combination (Catalano 2007). Perpetrators of IPV work to establish and maintain dependence in order to hold power and control over their victims, making them feel stupid, crazy, or ugly—in some way worthless.

IPV affects different segments of the population at different rates. The rate of IPV for Native American and Alaskan Native women is higher than any other race (Bureau of Justice Statistics 2017). The rate of IPV for Black women (4.6 per 1,000 persons over the age of twelve) is higher than that for White women (3.1). These numbers have been fairly stable for both racial groups over the last ten years.

Accurate statistics on IPV are difficult to determine, as it is estimated that more than half of nonfatal IPV goes unreported. It is not until victims choose to report crimes that patterns of abuse are exposed. Most victims studied stated that abuse had occurred for at least two years prior to their first report (Carlson, Harris, and Holden 1999). Also, studies and research methods apply a range of categories, which makes comparative or reinforcing data difficult to obtain. For example, some studies may only ask about IPV in two categories (for example, physical and sexual violence only) and may find fewer respondents reporting IPV than do studies that add psychological abuse, stalking, and technological violence.

Sometimes abuse is reported to police by a third party, but it still may not be confirmed by victims. A study of domestic violence incident reports found that even when confronted by police about abuse, 29 percent of victims denied that abuse occurred. Surprisingly, 19 percent of their assailants were likely to admit to abuse (Felson, Ackerman, and Gallagher 2005). According to the National Criminal Victims Survey, victims cite varied reasons why they are reluctant to report abuse, as shown in the table below.

| Reason Abuse Is Unreported | % Females | % Males |

|---|---|---|

|

Considered a Private Matter |

22 |

39 |

|

Fear of Retaliation |

12 |

5 |

|

To Protect the Abuser |

14 |

16 |

|

Belief That Police Won’t Do Anything |

8 |

8 |

Figure 6.22. This chart shows reasons that victims give for why they fail to report abuse to police authorities (Catalano 2007).

IPV against LGBTQ people is generally higher than it is against non-LGBTQ people. Gay men report experiencing IPV in their lifetimes less often (26 percent) than straight men (29 percent) or bisexual men (37 percent). 44 percent of lesbian women report experiencing some type of IPV in their lifetime, compared to 35 percent of straight women. 61 percent of bisexual women report experiencing IPV, a much higher rate than any other sexual orientation frequently studied.

Studies regarding intimate partner violence against transgender people are relatively limited, but several are ongoing. A meta-analysis of available information indicated that physical IPV had occurred in the lifetimes of 38 percent of transgender people, and 25 percent of transgender people had experienced sexual IPV in their lifetimes. Compared with cisgender individuals, transgender individuals were 1.7 times more likely to experience any IPV (Peitzmeier 2020).

Many college students encounter IPV, as well. Overall, psychological violence seems to be the type of IPV college students face most frequently, followed by physical and/or sexual violence (Cho & Huang, 2017). Of high schoolers who report being in a dating relationship, 10% experience physical violence by a boyfriend or girlfriend, 7% experience forced sexual intercourse, and 11% experience sexual dating violence. Seven percent of women and four percent of men who experience IPV are victimized before age 18 (NCJRS 2017). IPV victimization during young adulthood, including the college years, is likely to lead to continuous victimization in adulthood, possibly throughout a lifetime (Greenman & Matsuda, 2016)

6.8.3 Child Abuse

Children are among the most helpless victims of abuse. In 2010, there were more than 3.3 million reports of child abuse involving an estimated 5.9 million children (Child Help 2011). Three-fifths of child abuse reports are made by professionals, including teachers, law enforcement personnel, and social services staff. The rest are made by anonymous sources, other relatives, parents, friends, and neighbors.

Child abuse may come in several forms, the most common being neglect (78.3 percent), followed by physical abuse (10.8 percent), sexual abuse (7.6 percent), psychological maltreatment (7.6 percent), and medical neglect (2.4 percent) (Child Help 2011). Some children suffer from a combination of these forms of abuse. The majority (81.2 percent) of perpetrators are parents; 6.2 percent are other relatives.

Infants (children less than one year old) were the most victimized population with an incident rate of 20.6 per 1,000 infants. This age group is particularly vulnerable to neglect because they are entirely dependent on parents for care. Some parents do not purposely neglect their children; factors such as cultural values, standard of care in a community, and poverty can lead to hazardous level of neglect. If information or assistance from public or private services are available and a parent fails to use those services, child welfare services may intervene (U.S. Department of Health and Human Services).

A relief sculpture contains a three-dimensional hand and mouth with the words “I Will Be Heard.”

Figure 6.23. Dr. Michael C. Irving’s monument for child abuse survivors is composed of handprints and messages of people who have been victims of abuse.

Infants are also often victims of physical abuse, particularly in the form of violent shaking. This type of physical abuse is referred to as shaken-baby syndrome, which describes a group of medical symptoms such as brain swelling and retinal hemorrhage resulting from forcefully shaking or causing impact to an infant’s head. A baby’s cry is the number one trigger for shaking. Parents may find themselves unable to soothe a baby’s concerns and may take their frustration out on the child by shaking him or her violently. Other stress factors, such as a poor economy, unemployment, and general dissatisfaction with parental life, may contribute this type of abuse. While there is no official central registry of shaken-baby syndrome statistics, it is estimated that each year 1,400 babies die or suffer serious injury from being shaken (Barr 2007).

6.8.4 Licenses and Attributions for Violence in Family and Relationships

“Violence in Family and Relationships” by Heidi Esbensen is licensed under CC BY 4.0.

“DV/IPV and Child Abuse” is revised and adapted from “Challenges Families Face” by Tonja R. Conerly, Kathleen Holmes, Asha Lal Tamang, Introduction to Sociology 3e, which is licensed under CC BY 4.0

Figure 6.19. Advertisements by Dolce and Gabbana is included under fair use.

Figure 6.20. Images from Slutwalk DC CC BY-SA 2.0 by Ben Schumin .

Figure 6.21. Infographics from “Fast Facts: Preventing Intimate Partner Violence” by the CDC are in the Public Domain.

Figure 6.22. Table from “Challenges Families Face” is licensed under CC BY 4.0.

Figure 6.23. “Michael C. Irving’s Child Abuse Monument 9” by Harvey K is licensed under CC BY 2.0.