7.2 Gender Socialization Inside Education

Educational institutions regulate and guide our behaviors in many ways. Schools teach us many valuable and practical life skills, such as how to play an instrument or fix a leaky faucet. At the same time, education also serves to socialize students to the norms and expectations of society. We learn the importance of taking turns by raising our hands or exercising patience when waiting in a long cafeteria line.

Gender norms and expectations are learned through education. Which bathroom or locker room do you use at school? When there are only two options for school bathrooms or locker rooms, intersex or gender-neutral individuals must make a difficult personal choice every time they use the facility.

Gender socialization is most evident in schools that require dress codes based on perceived gender. These codes mean that students must present their hair, clothing, or other outer appearance based on a school’s recognition of their social or biological status, regardless of their gender expression.

7.2.1 Transmission of Knowledge and Career Tracking

As you grow throughout your education, dreams of your future take shape. These thoughts guide the courses you take in school and influence your future professions. Maybe you were good at math or writing, so you took more of those courses in high school. Did you notice any particular gender imbalances during your secondary education?

The education system has historically perpetuated gendered norms and roles in society. From the mid-1800s, women were educated to perform tasks such as cooking, household management, and childrearing. Universities focused on gendered academic majors such as elementary teachers, secretaries, and nurses for women. Classes such as math and sciences were thought to be only for men. Women’s education, and thus professional futures, were steered toward gender-normative traditional jobs. Times have changed, but education still funnels specific genders down a gendered career path (figure 7.1). Your own gender biases and stereotypes may have been challenged or reinforced when you were the only person of your gender in a car mechanics class or a family studies course.

Figure 7.1. Students in early education view their teachers as role models. Nationally, White women represent the majority of teachers. People of color and men are underrepresented in the teaching profession.

Did your school ever hold a career day? Or perhaps your parent or neighbor came into your classroom to share information about their workplace? Throughout our educational experience, we internalize impressions of who works in particular jobs or industries. Career tracking within our gender norms conversation means certain genders are subtly, or even overtly, steered down certain educational paths.

Academic tracking begins subtly and early in a student’s educational journey, with teachers dividing and re-grouping those who excel in certain areas such as language or math. High school students are more concretely divided by societal expectations. College-bound students take a set menu of courses, and students expected to directly enter the workforce or attend trade schools often take a different menu of courses. One way to address this inequity is to provide students with diverse representation of professionals across all demographics and spanning across all career paths. Students can then see themselves represented in career fields or industries they may have never realized were possible.

Education prepares us to be part of society first by transmitting knowledge. Formal education teaches students skills to succeed in particular careers. When you graduate from college or a trade school, you receive a degree or certificate stating you are fully educated in your field. Society then recognizes your qualifications. Employers even list requirements for a job such as “cardiopulmonary resuscitation certified (CPR)” or “project management certification.” This lets applicants know they must have formal training to be considered for the job.

Symbolic interactionist theorists refer to the importance of formal education documentation as “credentialism.” Workers show the symbol of knowledge with a formal certification document like a diploma or certificate of completion. Credentialism embodies the emphasis on certificates or degrees to show that a person has a specific skill, has attained a certain level of education, or has met specific job qualifications. Currently, more women in the United States receive bachelor’s degrees than men (National Center for Education Statistics N.d.). This is important because higher education degrees can level the playing field in the workplace, in terms of representation.

7.2.2 Dress codes

Dress codes are one strategy to neutralize gender and social class expectations in the learning environment. Most K-12 schools adhere to a dress code. Many restrict profanity on clothing and regulate varying levels of skin exposure. Some districts are stricter than others regarding student dress and have faced legal action questioning the validity of these regulations. In 2014, a federal appeals court struck down a requirement by an Indiana high school basketball team to maintain short hair (above ears and collar) because there was no similar restriction for females at the school. (Stempel 2014).

Dress code policies also create gender inequities, such as restricting female mid-rifts from showing but not specifying the same restrictions for males. Freedom of speech litigation is at the root of the issue, say parents and civil rights advocates. In the 1968 Tinker v. Des Moines Independent Community School District case, the U.S. Supreme Court found that freedom of speech laws apply in schools. Figure 7.2 shows students wearing school uniforms.

Figure 7.2. One of the intents of requiring student uniforms is to equalize student social hierarchies due to presentation of self by wearing expensive or trendy clothing.

Policies regulating physical presentation, such as hairstyle, face backlash across many communities due to inherent discrimination against students who are Black, indigenous, or people of color. Nonbinary and transgender students have been negatively impacted or even specifically targeted for wearing their hair or clothes in a way that matches their perceived gender instead of the one assigned to them at birth.

Students may not identify with gendered expectations for a particular hairstyle, such as Native Americans of all genders traditionally wearing their hair long. A school district in Texas was sued after suspending a Native American kindergartener for wearing long hair. Based on a finding of religious freedom, “schools must accommodate student religious beliefs in their dress codes and that applies as equally to Catholic students’ right to wear a rosary or Jewish students’ right to wear a yarmulke as it does to our American Indian client’s right to wear his braids” (American Civil Liberties Union 2010).

Religious clothing and freedom have been the focus of dress codes and resultant inequities in schooling. In particular, the hijab, the scarf Muslim women wear around their heads and upper bodies, has been a point of contention in educational institutions. Legal findings repeatedly confirm the protection of women’s rights to wear a hijab in school. Also, wearing a hijab at school sporting events has been upheld in the legal system. The confusion over federal, state, and local government regulations on gender-appropriate attire and presentation of self does muddy the waters in some instances.

7.2.3 Hidden Curriculum

Not all knowledge is formal in education. Educational institutions transmit knowledge in subtle ways, too. The informal transmission of knowledge and societal norms in education is known as the hidden curriculum. Gender stereotypes and cultural expectations for gender are a part of this hidden curriculum and are documented throughout different levels of the education system (Safta, 2017; Lee, 2014).

The way elementary school teachers interpret the behavior of boys or girls can affect how the education system labels students. Research has found that boys receive more attention in schools (Bassi, 2018). The consequence is that the “attention gap is correlated with lower scores in math for girls” (Bassi, 2018, p. 1). Girls’ performance in school suffers due to teachers paying more attention to boys in the classroom. Boys are more likely to be called on by teachers and receive more attention for positive and negative behaviors (Bassi 2018).

Boy’s behavior is often viewed as more disruptive in the classroom. Consequently, boys are referred to special education services more often than girls. Learning disabilities (LD) and education disabilities (ED) encompass a variety of behavioral and physical student needs. One study notes, “The greatest disparities are found for students with LD and students with ED where 73% and 76% of the students, respectively, are males” (Oswald et al. 2003, p. 224).

Education professionals are not the only influence guiding our understanding of gender in education. Many textbooks may only feature pictures of a family of heteronormative male/female partners with two racially similar and non-disabled children. Quite often, diverse families in our society do not receive equal representation in the course material.

Hidden curriculums extend to all levels of education. One study looking at medical students found the following:

Curricular emphases on women’s health and lack of support for male students to acquire gynecological examination skills were seen as explicit ways of excluding males. For female medical students, exclusion tended to be implicit, operating through modeling and aphoristic comments about so-called ‘female-friendly’ career choices and the negative impact of motherhood on careers. (Phillips 2009:847).

The research shows many ways education can guide our understanding of what jobs or skills are appropriate based on one’s gender identity. A variety of demographic representations used throughout school curriculum and in the education setting can help break down gender normative stereotypes and expectations (figure 7.3).

Figure 7.3. Two nonbinary people talk to each other in a school hallway.

7.2.4 Gender Role Formation and Sexuality Policing

At the beginning of this chapter, you were asked to think about your past teachers. Historically, males are more likely to obtain administrative roles and hold positions of power in educational institutions. Females are more likely to serve as teachers or staff at elementary and secondary grade levels. Why is this? Sociologists wonder what societal forces create gendered professions.

Early and secondary educators consist primarily of females. A 2017-2018 study found that about three-quarters of public school teachers were female, yet just under a quarter of school district superintendents are female (AASA 2022). As students see educators as their mentors, the lack of gender diversity at all levels hinders students’ ability to see themselves in different positions throughout the learning environment. The research confirms the positive effect on diverse student populations taught by diverse teachers (figure 7.4). Goldhaber, Theobald, and Tien (2019:26) found that “when empirical researchers have considered the effects of teacher diversity, they have generally found that, all else being equal (and, importantly, all else is often not equal), students of color do appear to benefit when they are taught by a teacher of the same race or ethnicity.”

Figure 7.4 An eighth-grade orchestra teacher helps a student cellist during a rehearsal. Students of color benefit in many ways from having teachers of color.

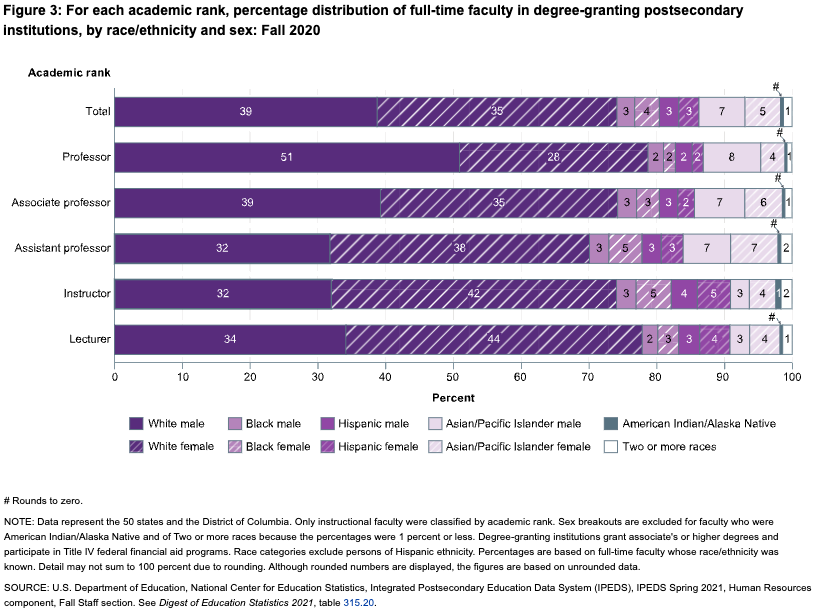

On a national level, men and women are more equally represented across all job roles within the higher education setting. However, men still outpace women in employment-secure, higher-paying positions such as professor and associate professor. Figure 7.5 from the National Center for Education Statistics (2022a) shows representation of gender and ethnicity in higher education teaching positions.

Figure 7.5. People who identify as Black or Hispanic are underrepresented in all higher education positions compared to representation in the United States.

Gender roles and norms for teachers and administrators are often passed along to students via implicit bias. Implicit bias is the unintentional belief or expression of bias. Students learn about expectations for a gender’s professional norms from all aspects of society including families, religion, peers, and other agents of socialization. Sociologists study these agents which pass along expectations for how a particular gender should look or act including what jobs they should hold.

7.2.5 Masculinity and Sports

Many primary and secondary schools feature organized sports in their curriculum. Athletics within the education system can serve to reinforce societal stereotypes related to gender. Sports have become representative of testing typically masculine traits and glorifying the strongest or fastest. Within the school system, girls and women were often expressly prohibited from participating in sports. There was concern that women could not handle the pressures of athletics and that it would negatively affect their fertility. As societal norms and expectations for equality transformed during the Civil Rights movements throughout the 1950s and 1960s, competitive sports in school also saw changes.

In 1972, a significant step towards gender equality in sports took place. That year, discrimination in education, including sports, was specifically prohibited by law. The law commonly known as Title IX states, “No person in the United States shall, on the basis of sex, be excluded from participation in, be denied the benefits of, or be subjected to discrimination under any education program or activity receiving Federal financial assistance” (U.S. Department of Education 2021). This law opened the doors for women’s participation in sports throughout the education system. The expansion of women into traditionally masculine sporting events at the high school level and in earlier grade levels continues.

We will discuss how to neutralize youth’s perceptions of athletic ability and body image later in this chapter when we look at single-gender classroom environments. Women’s participation in traditionally masculine sports such as wrestling, weightlifting, and soccer is now common (figure 7.6). Men are now more broadly accepted in traditionally feminine sports such as cheerleading and figure skating.

Figure 7.6. Female weightlifter.

7.2.6 Licenses and Attributions for Gender Socialization Inside Education

Credentialism definition is a key term from OpenStax Sociology 3e by Tonja R. Conerly, Kathleen Holmes, Asha Lal Tamang, which is licensed under CC BY 4.0.

Figure 7.1 Photo by CDC. License: Unsplash License.

Figure 7.2. Photo by Akshar Dave for unsplash. License: Unsplash License.

Figure 7.3 “Two non-binary talking to eachother in a school hallway” by Zackary Drucker from The Gender Spectrum Collection is licensed under CC BY-NC-ND 4.0.

Figure 7.4 Photo by Allison Shelley for EDUimages. License: CC BY-NC 4.0.

Figure 7.5 “For each academic rank, percentage distribution of full-time faculty in degree-granting postsecondary institutions, by race/ethnicity and sex: Fall 2020” in Characteristics of Postsecondary Faculty by National Center for Education Statistics is in the Public Domain.

Figure 7.6 Photo by John Arano on Unsplash

“All sections of Gender Socialization Inside Education” by Jane Forbes is licensed under CC BY 4.0.