7.3 Gender Segregation

Beliefs in academic ability by gender are rooted in historical views. From ideas that boys are more disruptive in classrooms to restricting girls’ participation in sports, education nurtures sex segregation in society. Education is not immune to gender inequality issues (figure 7.7).

Figure 7.7. [Gender inequity can be seen in this picture where student may be required to wear specific colors based on a binary gender identity for their graduation regalia. Nonbinary students may not be comfortable choosing a particular gender’s regalia color in order to conform to a school’s standards.]

Scientific research throughout history sought to prove a difference between men’s and women’s abilities. Research on the correlation between mental ability and gender began in the 1500s and continued for centuries, primarily driven by males. Throughout the mid-1800s, researchers stated they could visually show the physical differences in human brains, claiming that women’s brains were “less developed.” They also thought that because males were often physically larger than females, their brain size and capacity for learning were also bigger.

They believed a man’s ability to understand complex issues and control their emotions was greater than a woman’s (Shields 1975). George Romanes, a biology and physiology researcher in the late 1800s, wrote, “as a general rule the judgment of women is inferior to that of men has been a matter of universal recognition from the earliest times. The man has always been regarded as the rightful lord of the woman, to whom she is by nature subject, as both mentally and physically the weaker vessel” (Romanes 1887:385).

Researcher Helen Thompson Woolley graduated with a doctorate in Psychology from the University of Chicago in 1900, where she studied biological and social gender differences. Her findings were criticized throughout the research community when she noted that study results may differ due to the researcher’s biases and that societal influences are a significant factor in gender normative behaviors (Woolley 1914; Shields 1975).

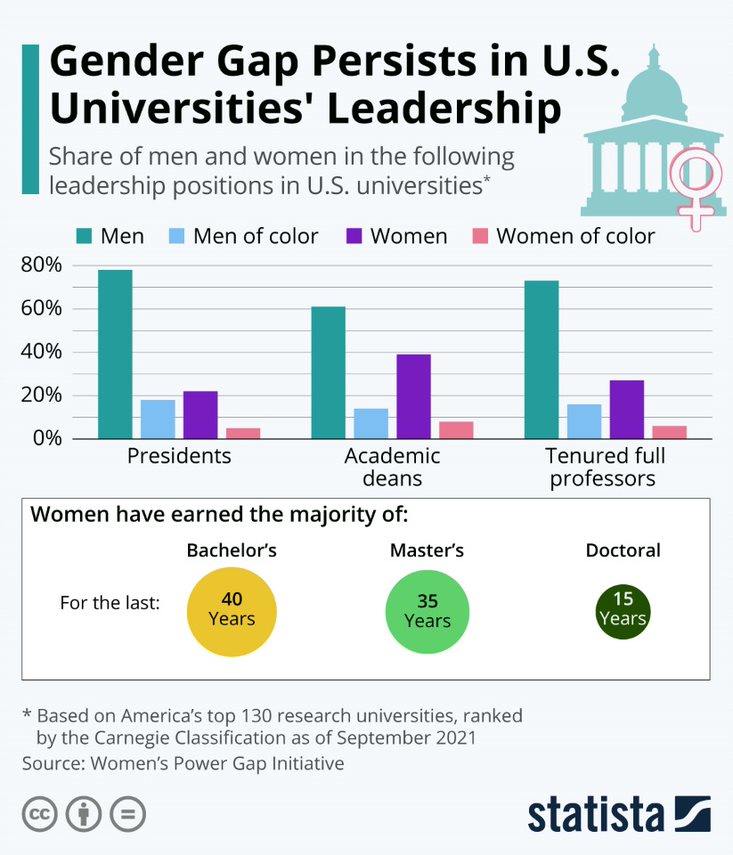

Over time, women and people of color have slowly gained access to all forms of education, including college. Since the late 1980s, women have outpaced men in obtaining bachelor’s degrees (National Center for Education Statistics N.d.). Although more women than men are now earning degrees, their representation in the upper levels of employment at educational institutions has not changed at a similar rate. One study found that “of the 130 public and private schools surveyed, 60 had never had a female president” (Fleck 2022). As we will discuss in Chapter 8, women and people of color are rarely employed in the upper levels of any industry, including education. Gender segregation in education often occurs at the highest institutional levels, as shown in figure 7.8.

Figure 7.8. [Academic Deans and Presidents of Universities, who hold the most power in education institutions, are most likely to be male and White. ]

Much like other places of work, women and people of color find it difficult to advance into positions of power. As the graphic illustrates, women and people of color are underrepresented in higher education administration and roles with power despite women now earning more degrees than White men. How and why this occurs in education is a familiar story, specifically highlighting “a lack of diversity in hiring practices, bias, and family life” (Moody 2018). In Chapter 8, you will learn more about gender equity issues the workplace.

7.3.1 Current Research on Gendered Performance

An argument for differing performance by gender in the education system is of possible biological influence over ability to succeed in some academic subjects. One study published in 2010 looked at data across a 17-year span between the 1990s and early 2000s. It found that “males and females perform similarly in mathematics” (Lindberg 2010:1123). A biological basis for gendered academic and learning ability has been disproven across many modern studies, including recent findings that the brains of all genders functioned similarly (Eliot et al. 2021). One study finds “that boys and girls engage the same neural system during mathematics development” (Kersey 2019:1).

Current research has contradicted such historical sexist ideologies. Early in life, females tend to outperform males academically and socially before entering formal education settings (Brandistuen et al. 2021).

Contemporary researchers agree that societal factors strongly influence the educational performance of students. Society often finds it tough to let go of deeply entrenched biological assumptions which lead to power inequity, even when science disproves those biases.

7.3.2 Segregated Schools

One argument to address gender gaps in education is to segregate classrooms, and even whole schools, by gender. Proponents of single-gender classrooms maintain that they reduce societal pressures to fulfill gender normative roles, such as females not being as adept at mathematics or males not being able to express their feelings freely.

Religious-based education programs have done this for many years. Single gender schools, religious based schools were originally created to reinforce gender-stereotypical norms. They trained girls for family support roles of traditional wives such as cooking and childcare, while boys learned job-related skills such as math and writing. This system leads to adult women with poor reading and writing skills needed in the workplace, thus unable to support themselves upon death of a spouse, divorce, or needing to escape from an abusive relationship.

The results of instituting single-gender classrooms across grades K-12 have been mixed. Some research shows that having additional school resources and increased attention from teachers for female-presenting students may have a stronger benefit than single-gender courses. Another concern about single-gender classes and schools is that they may impede students’ ability to build proper social skills with different genders, leading to poor workplace interactions and poor work performance. These students’ ability to understand others with different ideologies, lifestyles, or cultures may also be inhibited (Saunders N.d.).

One classroom environment that has consistently shown benefits for students is single-gender physical education courses. Physical education classrooms are particularly susceptible to peer and societal pressures to show strength, agility, body confidence, and overall fitness. The pressures increase even more in middle school, a time of rapidly changing bodies and minds. Single-gender physical education classrooms have been shown to increase perceived self-ability for females (Hannon and Ratliffe 2007; Slingerland et al. 2014). The theoretical basis for single-gender physical education is that gender-normative expectations and peer pressures are minimized in this learning environment.

Similar to physical education classrooms, single-gender secondary education schools often see students developing an improved self-concept. Single-gender secondary schools can create physical and emotional space for a stronger, non-gendered self-perception (Sullivan 2009).

However, single-gender public schools must garner support from policymakers and are difficult to establish as federal laws require equal gender access to funding and services. Education settings intended to be separate but equal are typically very unequal as history has shown in the pre-Brown v. Board of Education era of race segregation in schools. This complex issue includes ideologies that single-gender classes and schools perpetuate traditional gender norms. As historically seen in segregated education systems, inequity in curriculum and funding are also major concerns. A review of multiple studies across 45 years, through 2013, of over 1.66 million people from 21 countries found no benefit to single-sex classrooms for K-12 “students’ performance and attitudes in math and science; verbal skills; and attitudes about school, gender stereotyping, aggression, victimization and body image“ (Pahlke and Hyde 2017)

Mixed results have also been found in higher education. Some research on modern single-gender colleges finds students benefit academically and in the workplace. “Students in women’s colleges hold more positive views on equality in gender roles and manifest higher levels of self-esteem and self-control than women from coeducational colleges” (Riordan 1992). Detractors of single-gender colleges have concerns for students’ future ability to interact with diverse populations in the workplace.

7.3.3 Licenses and Attributions for Sex Segregation

Figure 7.7.Photo by Stocksnap is licensed under the Pixabay License.

Figure 7.8. Graphic by Statista Research Department is in the Public domain.

“All sections of Sex Segregation by Education” by Jane Forbes is licensed under CC BY 4.0.