7.4 Curriculum and Pedagogical Bias

Although teachers receive professional training in their own curriculum for recognizing and addressing stereotypes and bias, gendered norms and expectations are deeply rooted in our societal fabric. Early 2022 saw legislation in Florida restricting classroom conversations about sexual orientation and gender identity for kindergarten through fifth-grade students. The “Don’t Say Gay” bill allows people to take legal action against those they perceive are violating the bill. Supporters of the action maintain that conversations about LGBTQIA+ are the parent’s responsibility. Opponents insist it does not allow LGBTQ+ children to be themselves, thus negatively impacting their overall well-being. A survey by the public opinion research lab at the University of Florida in February 2022 found “overall opposition to the passage of the bill, with 49% opposing and 40% supporting either somewhat or strongly” (UNF PORL 2022).

Many studies have shown that teacher bias exists across all age levels and subjects. It was found that a mathematics teacher’s gender biased stereotypes influenced and widened performance gaps between genders, with their male students achieving higher success in the subject than their female students (Carlana 2019). As awareness of this issue grows, professional training educators on teacher and curriculum bias has become standardized.

Gender bias in education does not start and end with educators, as the curriculum itself can be biased. When we learn the material in any course, we must ask ourselves—is everyone’s story being told? However, awareness of implicit bias is growing. For example, Columbia University medical students created a reporting process “to identify and address instances of implicit bias” (Benoit et al. 2020:S145). As a result, curriculum changes were made within the program’s first year due to this collaborative effort by students and the university. So although curriculum and pedagogical bias exist, awareness of the issue and how to address it is becoming more common.

7.4.1 Power of Outside Forces and Authority Figures

There are efforts in the higher education system to counteract gender-normative expectations. Undergraduate, graduate, and teacher certification programs are working to address this by urging educators at the higher education level to encourage and support all genders equally. (Bhana and Moosa 2016). Males, often assuming administrative roles, are seen as authority figures in education. This gendered stereotype is further reinforced by teacher roles being predominantly filled with females. Researchers have examined this trend, finding that “men who choose to work as teachers face social pressures to adhere to dominant forms of masculinity—restricting children’s observations of masculinities and raising questions about what students inadvertently learn about masculinity in settings where male teachers are under-represented” (McGrath 2022:72). Employment demographics can be part of the hidden curriculum which reinforces a gendered power dynamic in education.

7.4.2 White Men as Knowledge Makers

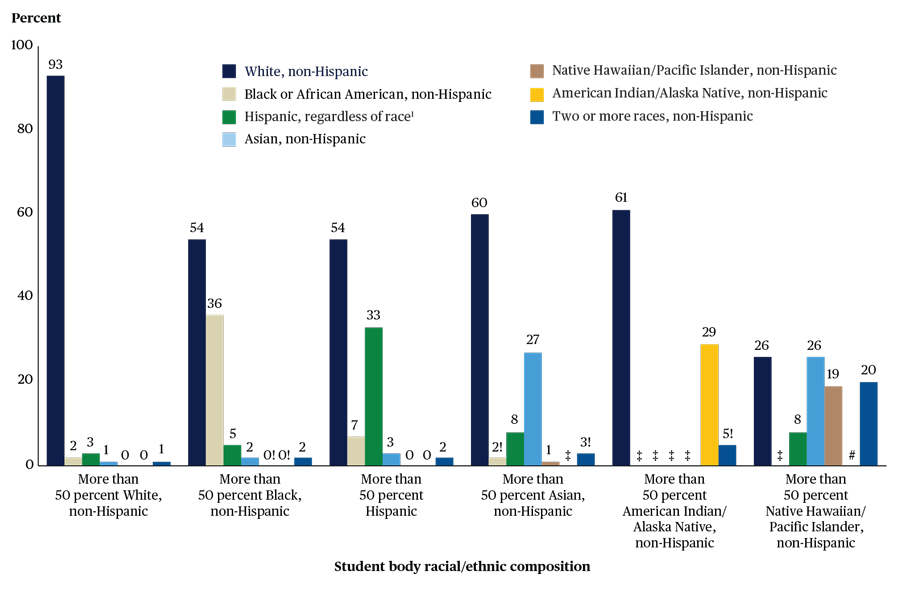

Figure 7.9. [Percentage of teachers by race/ethnicity for U.S. national student population by race/ethnicity. Although student populations may be racially and ethnically diverse, teacher populations are mostly White.] (National Center for Education Statistics 2022b).

Academic theorists, educational researchers, and administrators, including locally and federally, have been historically White, male, and heterosexual. The creation of academic content and curriculum has allowed their viewpoints and experiences to become mainstream and conventional.

Hovering around 2-3% of all public school teachers nationally, Black males are especially under-represented in the early education setting. Students have been found to positively respond to teachers who look like them and have similar life experiences (Egalite, Kisida, and Winters 2015; Hwang, Graff, and Berends 2022). Figure 7.9 from the National Center for Education Statistics (2022b) shows that even when student populations are racially or ethnically diverse, their teachers often significantly lack diversity.

Just over half of public school students were in “other than White alone” racial categories in 2020. Based on projections, the number of students of color will increase in future generations, and research supports positive achievement results for students of the same race/ethnicity as their teachers. This fact is especially true for struggling or low-achieving learners (Egalite, Kisida, and Winters 2015; Hwang, Graff, and Berends 2022).

Lack of support for non-cis students and emphasizing cis-normativity negatively impacts transgender and nonbinary students’ ability to learn in the formal education environment. (Horton 2020) Research shows that representation of all genders in teaching is important for adolescent development. Including nonbinary, transgender, male, female, and everyone along the gender spectrum from an early age in educational institutions means that “children begin to feel more confident about locating their bodies and identities outside of the male/female binary” (Wilkinson and Warin 2022).

7.4.3 Licenses and Attributions for Curriculum and Pedagogical Bias

Figure 7.9. “Percentage distribution of teachers, by race/ethnicity and the race/ethnicity of students at their school: 2017–18” in Race and Ethnicity of Public School Teachers and Their Students by the National Center for Education Statistics is in the Public Domain.

“All sections of Curriculum and Pedagogical Bias” by Jane Forbes is licensed under CC BY 4.0.