7.6 Social Change and Activism

Social change may occur slowly or be hard to pinpoint in the moment, but when we use our sociological lens longitudinally (across time), social change becomes more evident. Populations who traditionally had less access to power in education have gained education rights. Students with mental and physical disabilities gained the right to receive education at publicly funded schools with the Education for All Handicapped Children Act in 1975. “In 2018-19, more than 64% of children with disabilities are in general education classrooms 80% or more of their school day (IDEA Part B Child Count and Educational Environments Collection), and early intervention services are being provided to more than 400,000 infants and toddlers with disabilities and their families (IDEA Part C Child Count and Settings).” (U.S. Department of Education N.d.)

Oregon’s system of public higher education has also changed throughout its history. In 1914, the University of Oregon admitted its first Black student, Mabel Byrd. She was not allowed to live in the dorms on campus because she was Black. “Byrd lived in the home of history professor Joseph Schafer. There she worked as a domestic for the Schafer family while attending the university.”(O’Neal and Bigalke 2015). According to the University of Oregon library special collections and archives, she was also “the only Black resident of Eugene” (O’Neal and Bigalke 2015). Oregon State University’s first Black graduate was Carrie Halsell who graduated in 1926. She was also not allowed to live on campus because of her race. “In 2002, in honor of her immense courage, strength, and excellence, Oregon State University named a residence hall, Halsell Hall, in her honor, as she exemplified what it meant to overcome barriers for an education and additionally created opportunities for others to do the same. Halsell Hall is currently the only gender-inclusive living space on campus.” (Oregon State University N.d.).

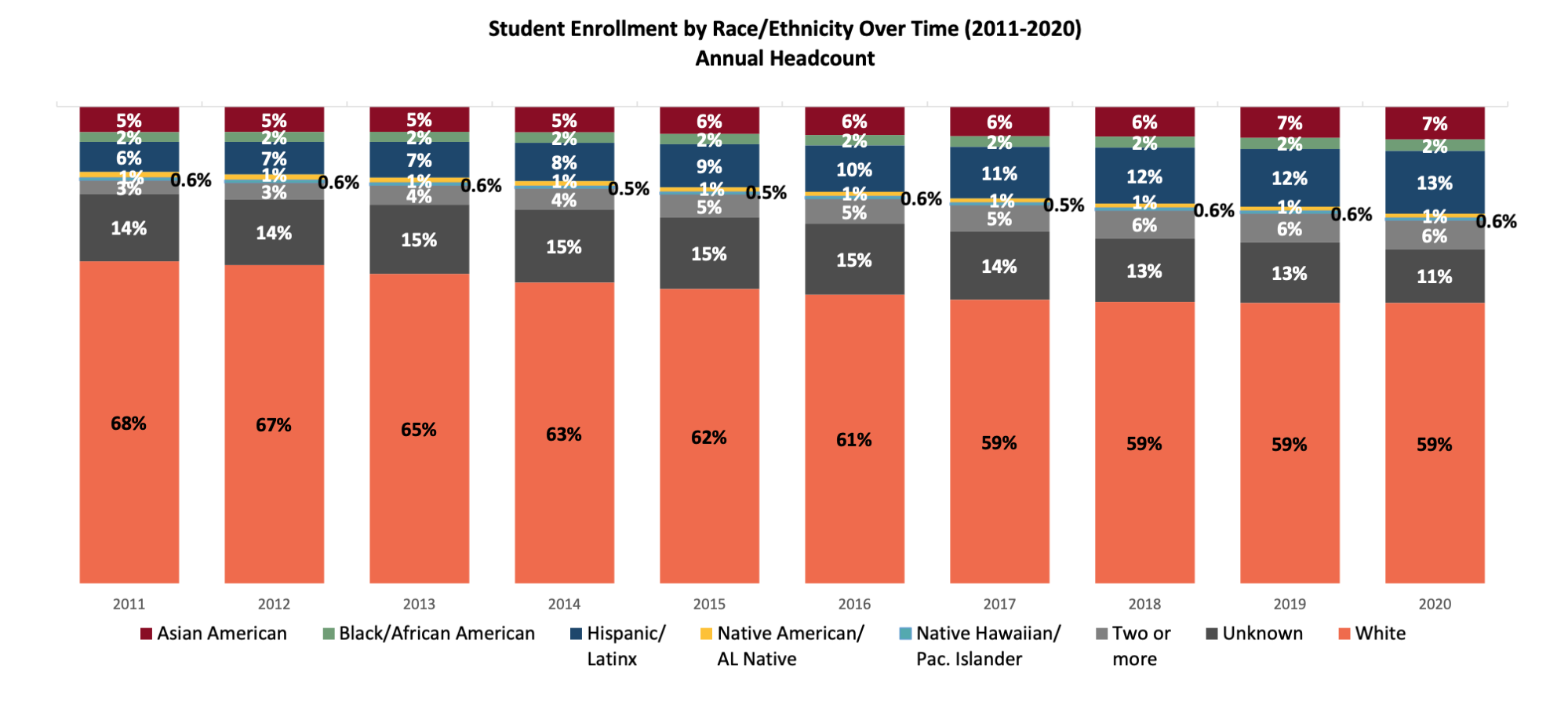

The number of students of color enrolled in higher education has increased over the last hundred years, but enrollment numbers are still not equivalent to their population growth. This inclusion of more diverse students and educators across all education levels was made possible by advocates pushing for social change. People who self-identify as Black or African American students only represent 2% of public university students in Oregon in 2020, though they made up 13.6% of the U.S. population in 2021. Hispanic or Latino students are also underrepresented at 13% enrollment, yet they comprised 19% of the U.S. population in 2021. White alone (not Hispanic or Latino) make up 59% of the students in Oregon’s public higher education system, reflecting the national U.S. population statistics for this racial category. People who identify as Asian are slightly overrepresented in the public university enrollment figure at 7%, with national representation at 6.1%. (Census.gov N.d.). Figure 7.12 Shows race demographics for public higher education institutions over a ten-year period.

Figure 7.12. [Race demographics for public higher education institutions in the state of Oregon for years 2011-2020. A majority of students across higher education institutions in Oregon identify as White, although people of color have been increasing over time.]

As of February 2021, Oregon’s public higher education system, which includes seven universities, reported a combined student population of 54% female, 45% male, and 1% unknown (Oregon.gov N.d.b). Oregon’s trend of more females than males graduating with college degrees is similar to national trends (National Center for Education Statistics N.d.).

Broadening the diversity of students, staff, administrators, and faculty means demand for academic programs throughout all levels of the education system has also changed. Language immersion programs are now common in elementary and grade schools. In middle and high schools, affinity groups bring together students with shared experiences or identities such as LGBTQIA+, families of adoption, and mentors for young women. In higher education, major and minor courses of study now include various options for diverse ethnic, cultural, and gender interests.

7.6.1 Women, Gender, and Queer Studies Programs

The education institution has maintained gender, sexuality, and race normative standards for a long time. Some groups seek to change these long-held standards in education. They hope to provide a more inclusive curriculum for all genders, sexualities, and ethnicities. Social constructionist theorists believe identity is built through our interactions with society and its expectations. Our gender, sexuality, and ethnic identity can change over time as we experience new things. This theoretical perspective can be applied to formal education systems where gender-normative expectations can lead to gender-traditional career choices, which affect an individual’s income and access to healthcare.

Educators are working toward creating more inclusive curriculums in order to give voice to all genders, sexualities, and ethnicities in society. Advocate groups collaborate with early and higher education systems to create inclusive educational paths for everyone. Providing students with a fuller understanding of all people in society will help them build their own internal and external identities.

Women’s studies became part of higher education curricula starting in the 1970s. The focus was on women’s history, power inequity based on gender, and women’s contributions to science, academia, and society (Guy-Shetall 2009). “Women’s studies” as a discipline changed over time as information and research evolved. Now, many departments focus on “gender and sexuality studies” or “feminist studies,” meaning all genders and sexualities are encompassed in the curriculum. (Bhatt N.d.).

Critics of women’s studies in academia maintain that the topic of gender is not useful, so has no place in higher education. In 2018, the prime minister of Hungary removed “accreditation from gender studies programs” (Redden 2018). A report on the incident by Inside Higher Ed, stated that “‘Gender studies’ has no business [being taught] in universities,” because it is “an ideology not a science,” a deputy to Hungary’s prime minister, Zsolt Semjen, told the international news agency Agence France-Presse.” (Redden 2018).

Queer studies also gained attention in the 1970s and achieved broader interest in the 1990s. In the last few decades, studies of the intersectionality of gender and sexuality, known as Queer studies, have increased. They are now recognized as important avenues for comprehensive research across disciplines. Researcher Miller writes, “From its earliest iterations, queer theory challenged norms that reproduced inequalities and, at its best, sought to understand how sexuality intersected with gender, race, class, and other social identities to maintain social hierarchies“ (Miller N.d.). Students of all genders and sexualities are now more represented in academic curricula than in the past. Figure 7.13 shows people of varying genders hanging out.

Figure 7.13. [Queer studies are becoming increasingly recognized as relevant to consider across academic disciplines including being it’s own major of study.]

7.6.2 Students of Minoritized Backgrounds

The study of other minority groups beyond gender and sexuality has also recently emerged in education. Classes focusing on varied cultures, races, and ethnicities have become commonplace at many colleges and universities. Chicana/o studies specifically look at Mexican-American experiences that are not typically part of traditional higher education courses. Starting in California in the mid-1960s and spreading across the United States today, these courses study Mexican Americans’ cultural dynamics and heritage. Latina/o studies have expanded the depth of courses offered, focusing on Latin American heritage and experiences.

Courses in Black, Africana, and African American culture and contributions to society were established in the 1960s and 1970s and gained momentum in recent decades. Dr. Jacob Gordon describes this field, stating that “Black Studies or African American Studies emerged as a multi-disciplinary academic field, primarily devoted to the study of the history, culture, and politics of peoples of African descent in the Americas.” It should be noted here that the field has been defined differently, linking it to the African Diaspora.

The field includes scholars of African American, Caribbean Studies; African Studies; Afro-European Literature; history; politics; geography; religion; as well as those from disciplines such as sociology, psychology, anthropology, cultural studies, linguistics, archeology, economics, education, law, race relations, and other disciplines in the humanities and the social sciences (Rojas, 2010); (Rogers, 2012); (Biondi, 2014).

Increasingly, the trend in African American Studies is partnering with academic units in the STEM (Science, Technology, Engineering, and Mathematics) area (Gordon and Acheampong, 2016).” (Gordon N.d.). Once considered specialty courses, independent of other academic classes, these courses are now requirements for many disciplines. They have even become major educational tracks from associate degrees to doctoral programs.

Studies of non-Eurocentric cultures and languages have moved beyond higher education, connecting these arts, customs, languages, and experiences to students as early as kindergarten. Foreign language learning has expanded to include immersion tracks starting as early as kindergarten in some districts. The Portland (Oregon) Public School district offers immersion language programs starting in kindergarten for Spanish, Vietnamese, Russian, Chinese, and Japanese as of 2022 (Portland Public Schools 2020).

7.6.3 Organizations and Movements for Change

Organizations advocating for change related to sexual assault and violence exist across the United States. The anti-sexual violence group, RAINN (Rape, Abuse & Incest National Network) runs the National Sexual Assault Hotline. According to their website, “RAINN also carries out programs to prevent sexual violence, help survivors, and ensure that perpetrators are brought to justice” (RAINN N.d.a). Men Can Stop Rape was created in the late 1990s to focus on reducing or eliminating violence against women. Their aim is for “reimagined prevention, recasting responsibility and engaging men as allies by promoting healthy, nonviolent masculinity” (Men Can Stop Rape N.d.).

Social media has helped spread the word about campus and society-wide sexual violence with the hashtags #metoo and #sayhername. The #sayhername movement works towards the acknowledgment of Black women whose deaths by police violence are systemically and severely underreported in the media. “Knowing their names is a necessary but not a sufficient condition for lifting up their stories which in turn provides a much clearer view of the wide-ranging circumstances that make Black women’s bodies disproportionately subject to police violence.” (African American Policy Forum N.d.). The group also seeks to support victims’ families.

Starting in late 2017, women across social media used #metoo to publicize their personal histories of sexual assault and violence. At that time, multiple high-profile people with societal power were accused of sexual harassment and violence, some of whom faced legal ramifications. 10 years prior, activist Tarana Burke created the MeToo Movement which focused on assisting sexual assault victims (#moveme N.d.). As students in all levels of education are an integral part of society, these groups and others seek to bring attention to and support victims of sexual violence in schools.

7.6.4 Campus Culture

Title IX was a landmark finding allowing all genders in publicly funded education settings to pursue athletics. It could not have been possible without the tireless efforts of activists pushing for societal and legislative change. United States Representative Patsy Takemoto Mink of Hawaii was the sponsor and author of the bill known as Title IX (figure 7.14). She was “the first Asian-American woman and just the second woman from Hawaii to serve in Congress.”(History, Art, and Archives N.d.). Rep. Mink recounted her experience in 1974 fighting for gender equity saying “there were only eight women at the time who were Members of Congress, that I had a special burden to bear to speak for [all women], because they didn’t have people who could express their concerns for them adequately. So, I always felt that we were serving a dual role in Congress, representing our own districts and, at the same time, having to voice the concerns of the total population of women in the country.” (History, Art, and Archives N.d.).

Figure 7.14. 100 Women of the Year 1972: Patsy Takemoto Mink (c) Time USA, LLC/Gwendolyn Mink/Patsy Takemoto Mink papers, Library of Congress. Used under fair use.

Take Back The Night (TBTN) is another movement advocating for victims of sexual violence. First used in the late 1970s to describe an anti-violence march, it has evolved into hundreds of organized global events, with many occurring every year on campuses and communities across the United States. The TBTN Foundation supports “ending sexual violence for all people around the globe. We seek to educate and change policies and cultural norms to create cultures of respect in every space and place around the world” (Take Back the Night foundation N.d.). Gender-based violence in schools is not only prevalent in the United States but globally. Many agencies such as TBTN are working to bring attention and resources to students experiencing violence in schools.

The United Nations Girl’s Education Initiative (UNGEI) and the Together for Girls organization (part of the United Nations Aids program) seek to improve females’ quality of life, safety, and health globally. “Together for Girls is a global partnership working to end violence against children and adolescents, particularly sexual violence against girls.” (Together for Girls N.d.).

The UNGEI’s mission is “Harnessing the power of collective action, the UNGEI partnership is on a mission to close the gender gap in education and unlock its transformative power for every girl, everywhere. We champion the rights of girls to a quality education in a safe and gender-sensitive learning environment and hold the international community to account for commitments made to gender equality in and through education” (United Nations Girls’ Education Initiative. N.d.). Activist groups, large and small, near and far, are working toward safe learning environments and equal opportunity in education for all genders.

7.6.5 Licenses and Attributions for Social Change/Activism

Figure 7.12. “Student Enrollment by Race/Ethnicity Over Time” by the Higher Education Coordinating Commission, Oregon.gov is included under fair use.

Figure 7.13. “A group of friends of varying genders at a party” by The Gender Spectrum Collection is licensed under CC BY-NC-ND 4.0.

Figure 7.14. 100 Women of the Year 1972: Patsy Takemoto Mink (c) Time USA, LLC/Gwendolyn Mink/Patsy Takemoto Mink papers, Library of Congress is included under fair use.

“All sections of Social Change/Activism” by Jane Forbes is licensed under CC BY 4.0.